1018 Taxpundit 0112

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotlaw 2014

Ramsharan Autyanuprasi and Another Vs Union of India and Others Writ Petition (Civil) No. 442 of 1988 (S. Ranganathan, Sabyasachi Mukharji JJ) 14.11.1988 JUDGMENT SABYASACHI MUKHARJI, J. – 1. This is a petition under Article 32 of the Constitution, filed by Ramsharan Autyanprasi and Vijendra Singh. They assert that it is public interest litigation. This petition was addressed to one of the learned Judges of this Court by name. 2. The petitioners state that they wanted to bring to the notice of the Judge the total disarray caused by the arbitrary and high-handed running of the premier institution of ancient art, culture and history in Rajasthan, namely, the "Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust" by its Chairman Lt. Col. Sawai Bhawani Singh. They further state that since they are the concerned citizens of the State and the country, it is their duty to seek court's intervention in this matter. It is asserted that in Jaipur, Rajasthan, the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh matter. It is asserted that in Jaipur, Rajasthan, the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust had been created by late Maharaja Sawai Man Singh as Public Trust and the same was registered as a Public Trust under the provisions of the Rajasthan Public Trust Act, 1959(Rajasthan Act 42 of 1959). 3. The petitioners state that Lt. General Maharaja Rajendra Maharaj Dhiraj Sawai Man Singh of Jaipur and his predecessors, rulers of erstwhile Jaipur State had founded the museum for the benefit of the public, in a portion of the City Palace, Jaipur and this museum has a large number of items of value and is being used for the benefit of the public of the State of Jaipur and by visitors to that State. -

Cradle of Leadership This Rich Shade of Maroon Was Adopted As the National Defence Academy Colour in 1956

CRADLE OF LEADERSHIP This rich shade of maroon was adopted as the National Defence Academy colour in 1956. It is a synthesis of Olive Green of the Army, Prussian Blue of the Navy, Sky Blue of the Air Force, and Red, the colour of valour and sacrifice. THE CREST of THE Nationa L DEFENCE ACADEMY Designed to foster the spirit of camaraderie among the Services, the insignia is composed of symbols that represent the Army, the Navy and the Air Force. The cross swords stand for the Army’s martial valour, the anchor denotes the stability of the Navy and the Himalayan eagle symbolises the Air Force’s aspiration to touch the skies with glory. The four Asiatic lions standing back to back, adopted from the national emblem and mounted on the Himalayan eagle, depicts pride in serving the motherland while the scroll at the base endorses the ideal of Seva Paramo Dharma or Service before Self. First chosen in 1948, the design of the insignia evolved between 1949 and 1956. © national defence academy May 2016 Executive Publisher Maneck E Davar Compiling Editor Commander Aman Singh Siwach Editorial Monideepa Choudhuri Design Parvez Shaikh Vaishali Kapadia Jhaveri Rohit Nayak Ninad Jadhav Photography Dhiman Chatterjee Baldev Singh, LA(PH) Acknowledgements: For their guidance and advice: Vice Admiral G Ashok Kumar, PVSM, AVSM Commandant, NDA NATIONAL DEFENCE ACADEMY Air Vice Marshal S P Wagle, VM Deputy Commandant, NDA CRADLE OF LEADERSHIP Brigadier S K Rao, YSM Brigadier Administration, NDA 1949 - 2016 Prof (Dr) O P Shukla Principal, NDA Captain Devanshu Rastogi Director Training, NDA For their able support: Commander K Nirmal Lieutenant Colonel B D Lenka Major Himani Luthra Captain Kartikeya Manral Captain Bibek Pradhan Mr Anand (Anand Photo Studio) All training teams and Adjutant’s section NDA Archives Section Printed and Designed by No part of this book may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. -

Pre-Feasibility Report

NON- FOREST LAND PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT FOR MASONRY STONE MINE (MINOR MINERAL) NEAR VILLAGE – KHOHARA THAKARAN, TEHSIL: KOTKASIM, DISTRICT: ALWAR, RAJASTHAN CATEGORY – A (Interstate Boundary of Haryana –Rajasthan lies within 5.0 km Radius) MINING LEASE AREA :1.0 HA. PURPOSE PRODUCTION CAPACITY : 50,000 TPA M.L No. - 135/02, KHASRA No. – 15, 536 PROPONENT SHRI HANUMAN SINGH S/O Sh. Bhawani Singh R.O. Livana, Tehsil Kishangarh, Distt. Alwar (Raj.) EIA CONSULTANT OVERSEAS MIN-TECH CONSULTANTS ISO 9001:2008 Certified & NABET Accredited EIA Consultants 501, 5th Floor, Apex Tower, Tonk Road, Jaipur-302015 Telefax: +91-141-2744509, Mobile: +91-9460221084 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.overseasmintech.com Masonry Stone Mining Project (50,000 TPA), M.L. No.135/02 ML Area 1.0 Pre-Feasibility Report ha., Near Village: Khohara Thakaran, Tehsil- Kotkasim, District- Alwar Index (Rajasthan) Sh. Hanuman Singh S/O Shri Bhawani Singh INDEX 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 1 2 INTRODUCTION OF THE OBJECT/ BACKGROUND INFORMATION ........ 3 2.1 IDENTIFICATION OF PROJECT AND PROJECT PROPONENT ........................................... 3 2.2 NEED FOR THE PROJECT & ITS IMPORTANCE TO THE COUNTRY/ REGION ........................ 4 2.3 DEMAND – SUPPLY GAP ............................................................................................................. 4 2.4 IMPORTS VS. INDIGENOUS PRODUCTION ............................................................................... -

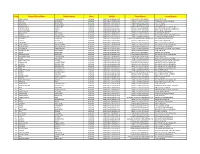

S No Name of Candidate Fathers Name State Rollno Tradealloted

S No Name OF Candidate Fathers Name State RollNo TradeAlloted Arms/Service 1 DINESH KUMAR HARIOM SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47002 STORE KEEPER TECHNICAL{SKT} ARTY CENTRE, NRC 2 BIJENDER RAM KISHAN HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47003 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} DOGRA REGT CENTRE, FAIZABAD 3 ANIL KUMAR BHOPAL SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47005 STORE KEEPER TECHNICAL{SKT} 2 STC, PANJI GOA 4 AMIT KUMAR BALWAN SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47012 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} 1 STC, JABALPUR 5 SANDEEP KUMAR SUMER SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47013 STORE KEEPER TECHNICAL{SKT} ASC CENTRE {SOUTH}, BANGALORE 6 PARVEEN KUMAR RAMPAL HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47014 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} GARHWAL RIFLES CENTRE, LANSDOWNE 7 RAVINDER KUMAR AJMER HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47022 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} ARTY CENTRE, HYDERABAD 8 AMIT KUMAR UMED SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47023 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} 3 EME CENTRE, BHOPAL 9 VIKRAM MANGAT RAM HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47026 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} PUNJAB REGT CENTRE, RAMGARH CANTT 10 RAVIKANT GOYAL SUBHASH GOYAL HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47031 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} DOGRA REGT CENTRE, FAIZABAD 11 DEVENDER RAMMEHAR HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47033 CLERK{CLK} INVENTORY MANAGEMENT {IM} AOC CENTRE SECUNDERABAD 12 KULDEEP JAI SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47036 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} CMP CENTRE, BANGALORE 13 RANDHAWA SATBIR SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47038 CLERK{CLK} STAFF DUTIES{SD} AAD CORPS CENTRE, GOPALPUR 14 SUMIT KUMAR BAHADUR SINGH HARYANA AMB/CHA/CL/260415/47040 -

(Enter District Name) Division Name & Code No. of P&GS Unit Address Of

List of LIC Offices for servicing of PMJDY Claim Search (Enter District Name) Search Results… Division Name & code no. of P&GS unit Address of the P&GS unit Phone no. of unit E-mail ID of the Unit Name of Districts / state to which unit will provide service State name Name of the Branch Official mobile number of Branch official If the "District Name" you are searching is in the list, it will be displayed in the search "Search Result...". If the "District Name" you are searching is not in the database it will display "#N/A" in all the fields except "District Name" field. NameofDistricts/stateto Name of the Branch mobile number of Zone Division Name & code no. of P&GS unit Address of the P&GS unit Phone no. of unit E-mail ID of the Unit whichunitwillprovideservi State name Official Branch official ce LIC OF INDIA KADAPA KADAPA-G-502 P&GS Unit 08562-244680 [email protected] Kurnool A.P Sri SRINIVASAN C 94448 55578 C/O LIC OF INDIA LIC OF INDIA KADAPA KADAPA-G-502 P&GS Unit 08562-244680 [email protected] Y.S.R (Kadapa) A.P Sri SRINIVASAN C 94448 55578 C/O LIC OF INDIA LIC OF INDIA KADAPA KADAPA-G-502 P&GS Unit 08562-244680 [email protected] Anantapur A.P Sri SRINIVASAN C 94448 55578 C/O LIC OF INDIA LIC OF INDIA KADAPA KADAPA-G-502 P&GS Unit 08562-244680 [email protected] Chittoor A.P Sri SRINIVASAN C 94448 55578 C/O LIC OF INDIA LIC OF INDIA KADAPA KADAPA-G-502 P&GS Unit 08562-244680 [email protected] S.P.S Nellore A.P Sri SRINIVASAN C 94448 55578 C/O LIC OF INDIA III Floor,"JeevanKrishna" MACHILIPATNAM VIJAYAWADA G-505 Besant -

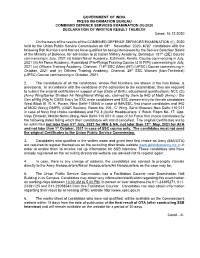

GOVERNMENT of INDIA PRESS INFORMATION BUREAU COMBINED DEFENCE SERVICES EXAMINATION (II)-2020 DECLARATION of WRITTEN RESULT THEREOF Dated: 16.12.2020

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS INFORMATION BUREAU COMBINED DEFENCE SERVICES EXAMINATION (II)-2020 DECLARATION OF WRITTEN RESULT THEREOF Dated: 16.12.2020 On the basis of the results of the COMBINED DEFENCE SERVICES EXAMINATION (II), 2020 held by the Union Public Service Commission on 08th November, 2020, 6727 candidates with the following Roll Numbers and Names have qualified for being interviewed by the Service Selection Board of the Ministry of Defence, for admission to (i) Indian Military Academy, Dehradun 151th (DE) Course commencing in July, 2021 (ii) Indian Naval Academy, Ezhimala, Kerala, Course commencing in July, 2021 (iii) Air Force Academy, Hyderabad (Pre-Flying) Training Course (210 F(P)) commencing in July, 2021 (iv) Officers Training Academy, Chennai 114th SSC (Men) (NT) (UPSC) Course commencing in October, 2021 and (v) Officers Training Academy, Chennai, 28th SSC Women (Non-Technical) (UPSC) Course commencing in October, 2021. 2. The candidature of all the candidates, whose Roll Numbers are shown in the lists below, is provisional. In accordance with the conditions of the admission to the examination, they are required to submit the original certificates in support of age (Date of Birth), educational qualifications, NCC (C) (Army Wing/Senior Division Air Wing/Naval Wing) etc. claimed by them to IHQ of MoD (Army) / Dte Gen of Rtg (Rtg A) CDSE Entry for SSC male candidates and SSC women entry for female candidates West Block III, R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 in case of IMA/SSC first choice candidates and IHQ of MOD (Navy) DMPR, (OI&R Section), Room No. 204, ‘C’ Wing, Sena Bhawan, New Delhi-110 011 in case of Navy first choice candidates and PO 3 (A)/Air Headquarters ‘J’ Block, Room No. -

05.10.2018 J- 1 Pronouncement of Judgement(Applt.Jurisdiction)

05.10.2018 J- 1 PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGEMENT(APPLT.JURISDICTION) 05.10.2018 COURT NO.37 (DIVISION BENCH-II) HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE S.RAVINDRA BHAT HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.K.CHAWLA AT 2.30 P.M. 1. GTR 2/1981, C.M. APPL. 5764/2013 & 45861/2016 (lead case) COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX ..... Petitioner versus BHAWANI SINGHJI ..... Respondent 2. ITA 152/2001 COMMISSIONER OF I.T. DELHI-V ..... Appellant versus RAJ MATA GAYATRI DEV ..... Respondent 3. ITA 218/2002, C.M. APPL.5766/2013 CIT ..... Appellant versus RAJ MATA GYATRI DEVI OF JAIPUR ..... Respondent 4. ITA 679/2004, C.M. APPL.5757/2013 COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX ..... Appellant versus RAJMATA GYATRI DEVI ..... Respondent 5. ITA 163/2005 COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX DELHI ..... Appellant versus RAJMATA GAYATRI DEVI OF JAIPUR ..... Respondent 05.10.2018 J- 2 PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGEMENT(APPLT.JURISDICTION) 6. ITA 750/2007 THE COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX V ..... Appellant versus MAHARAJA JAI SINGH ..... Respondent 7. ITA 752/2007 THE COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX ..... Appellant versus MAHARAJA JAI SINGH INDL. ..... Respondent 8. ITA 751/2007; ITA 763/2007 THE COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX-V ..... Appellant versus MAHARAJA PRITHVI RAJ ..... Respondent 9. ITR 137/1983; ITR 78/1981& ITR 397/1983 CIT ..... Petitioner versus JAI SINGH ..... Respondent 10. ITR 297-98/1981 COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX ..... Petitioner versus BHAWANI SINGHJI ..... Respondent 11. ITR 9/1982, C.M. APPL.5772/2013 CIT ..... Petitioner versus BHAWANI SINGH ..... Respondent 05.10.2018 J- 3 PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGEMENT(APPLT.JURISDICTION) 12. ITR 46-47/1982 CIT ..... Petitioner versus GAYATRI DEVI ..... Respondent 13. -

(II)-2019 DECLARATION of WRITTEN RESULT THEREOF Dated: 01.11.2019

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS INFORMATION BUREAU COMBINED DEFENCE SERVICES EXAMINATION (II)-2019 DECLARATION OF WRITTEN RESULT THEREOF Dated: 01.11.2019 On the basis of the results of the COMBINED DEFENCE SERVICES EXAMINATION (II), 2019 held by the Union Public Service Commission on 08th September, 2019, 8120 candidates with the following Roll Numbers have qualified for being interviewed by the Service Selection Board of the Ministry of Defence, for admission to (i) Indian Military Academy, Dehradun 149th (DE) Course commencing in July, 2020 (ii) Indian Naval Academy, Ezhimala, Kerala, Course commencing in July, 2020 (iii) Air Force Academy, Hyderabad (Pre-Flying) Training Course (208 F(P)) commencing in July, 2020 (iv) Officers Training Academy, Chennai 112th SSC (Men) Course (NT) commencing in October, 2020 and (v) Officers Training Academy, Chennai, 26th SSC Women (Non-Technical) Course commencing in October, 2020. 2. The candidature of all the candidates, whose Roll Numbers are shown in the lists below, is provisional. In accordance with the conditions of the admission to the examination, they are required to submit the original certificates in support of age (Date of Birth), educational qualifications, NCC (C) (Army Wing/Senior Division Air Wing/Naval Wing) etc. claimed by them to IHQ of MoD (Army), Rtg ‘A’, CDSE Entry, West Block-III, R.K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 in case of IMA/SSC as their first choice and Naval HQ “DMPR” (OI & R Section), Room No. 204, ‘C’ Wing, Sena Bhawan, New Delhi-110011 in case of Navy as their first choice, and PO3(A)/Air Headquarters, ‘J’ Block, Room No. -

Rajmahal Palace Is One of the Oldest and Most Treasured Properties in the ‘Pink City’ of Jaipur

Exceptional travel experiences with quintessential charm, inimitable style and sublime service. Rajmahal Palace is one of the oldest and most treasured properties in the ‘Pink City’ of Jaipur. Belonging to the Royal Family of Jaipur, this exquisite private palatial home is set in the prime location in the center of Rajasthan’s bustling capital. An enclosed oasis, secluded in exquisite gardens, Rajmahal Palace eludes a sense of celebrated history. The tall bay windows, mirrored doors and exquisite interior décor allow guests to be transported to a new era of regal living. A PALACE WITH A GLAMOROUS PAST Over the decades this remarkable Palace has hosted Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth & the Duke of Edinburgh to stay at Rajmahal Palace, along with several other members of the British Royal Family. Celebrated personalities such as Jackie Kennedy, Lord & Lady Mountbatten and many of the international ‘jet set’ have been part of the history and enjoyed the wonderous hospitality within the Palace walls. RAJMAHAL PALACE Initially compromising of 14 Royal Apartments, Suites and Palace Rooms we invite guests to be a part of the future of Rajmahal Palace and share this extraordinary home with us. THE GROUNDS The Palace lawns and gardens provide exquisite spaces for dining, teas or just a spoiling afternoon spent reading a book with a glass of wine. Set against the celebrated façade of the Palace exteriors, the grounds are a verdant respite, right at the heart of Jaipur City. THE DESIGN After careful and meticulous restoration work, by celebrated designer Adil Ahmad, the Palace successfully embodies the heritage of it’s past life, maintaining the original, stunning marble staircase, intricate chandeliers, and treasured family possessions, whilst transporting guests into a new Era. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR ND THURSDAY,THE 22 JANUARY,2015 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 1 TO 59 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 60 TO 64 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 65 TO 80 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 81 TO 99 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 22.01.2015 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 22.01.2015 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW FOR ADMISSION 1. LPA 521/2014 DR. NIRJA SHARMA AND ORS MRS. PRATIBHA SINHA CM APPL. 13008/2014 Vs. UNIVERSITY OF DELHI AND ORS CM APPL. 13726/2014 WITH LPA 546/2014 2. LPA 546/2014 UNIVERSITY OF DELHI MOHINDER SINGH,ANKIT JAIN CM APPL. 13636/2014 Vs. VEENA GAUR AND ORS WITH LPA 521/2014 AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 3. LPA 600/2014 JAIN SHWETAMBER KALYANAK ANUP JAIN AND ABHISHEK TIRTH NAYAS BAID,JAYESH GAURAV,SUBHASH Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ORS SHARMA 4. LPA 702/2014 GURBACHAN SINGH C AND B ASSOCIATES,VIKRAM Vs. UOI AND ORS JETLEY 5. W.P.(C) 3903/2011 DEEPAK ANAND PET IN PERSON,SONIA Vs. UOI AND ORS MATHUR,ABHAY P SAHAY 6. W.P.(C) 2992/2013 COMMON CAUSE RISHI AGRAWALA,GOPAL CM APPL. 5648/2013 Vs. SUBHASH JAIN SINGH,MEDHANSHU TRIPATHI,ALOK CM APPL. 12086/2013 EX-COUNCILLOR AND ORS SANGWAN,RAGHAV SHANKER,ASHISH MOHAN,ZUBEDA BEGUM,MEHAK KANWAR,SAGAR DAWAR,B.C.BHATT,RAJESH PATHAK,VINAY GUPTA CONNECTED MATTERS (ANMM) 7. -

Name Telephone Email ID Sanjay Kumar Mishra Dir

DIRECTORATE OF ENFORCEMENT 6TH FLOOR, LOKNAYAK BHAWAN, KHAN MARKET, NEW DELHI-110 003 Fax No. 011- Email: [email protected] 2463-1847 Name Telephone Email ID Sanjay Kumar Mishra Dir. 24693577 [email protected] Simanchala Dash Pr. Special Director 246D3460 D.K. Gupta Special Dir. 24623015 [email protected] Deepak Kumar Kedia Addl. Dir. 24640466 [email protected] dla-ed- A.C. Singh Dy. Legal Advisor 24619133 [email protected] Rahul Rajput Jt. Dir. 24690289 [email protected] sanjay.lawania@icegate. Sanjay Lawania Jt. Dir. 24640466 gov.in Nikhil Govila Jt Dir 24653462 [email protected] Rajeshwar Singh Jt. Dir. 24642672 [email protected] J.P. Singh DD 24642643 [email protected] Ashok Gautam DD 24626105 [email protected] A.K. Kaushal DD 24648957 [email protected] Delhi Zonal Office MTNL Building, 1st and 2nd Floor, J.L. Nehru Marg, New Delhi-110003. Tel : 011-23387828 Satyendra Mathuria Joint Director 23387828 Vikas Singh DD 23073860 Neeraj Gupta Jt.Dir. Patna Zonal Office 1st Floor, Chandpura place, Bank Road, West Gandhi Maidan, Patna-800001 STD- 0612 Sanjay Lawania Jt. Director 2219443 Lucknow Zonal Office, Princeton Business Park, 2nd Floor, 16-Ashok Marg, ucknow-26001 (U.P.) STD: 0522 Dr. Rajeshwar Singh Jt. Dir. 2288617 Jaipur Zonal Office, 2nd Floor, Jeevan Nidhi-II, LIC Building, Bhawani Singh Road, Jaipur-302005. STD: 0141 2741173 Rahul Rajput Jt. Dir. 2741174 Ashok Gautam DD 2741175 Ranchi Sub Zonal Office, Pepee Compund, Kaushlya Chamber-II, Main Road, Ranchi-834001. STD: 0651 DD 2332737 Allahabad Sub Zonal Office, 3, B.K. -

'Dharohar' Heritage Film Festival in Jaipur

PRESS RELEASE ‘DHAROHAR’ HERITAGE FILM FESTIVAL IN JAIPUR Showcasing the best of our historic, cultural & natural heritage to children Gunijankhana and Sukhnidhey Films in collaboration with the Association of British Scholars Jaipur Chapter are organizing ‘Dharohar Film Festival’ at the Banquet Hall, City Palace Jaipur on April 7th- 8th, 2015 from 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM. A Heritage themed Film Festival showcasing the best of the films on our incredible heritage to school children, the unique festival aims to spread awareness amongst the youth for the conservation of our rich historic, cultural and natural heritage in its diverse forms, so that the younger generation feels proud of our glorious heritage & culture. HRH Princess Diya Kumari of the Jaipur Royal Family and Shri Shailendra Agarwal, IAS, Principal Secretary of Tourism, Art & Culture- Government of Rajasthan would grace the event and inaugurate the festival on April 7th at 10:00 AM. The festival would feature film screenings and interactive sessions with filmmakers, archaeologists and experts who would share their insight and experiences with the youth, inspiring them to be the change. Gunijankhana: Maharaja Sawai Bhawani Singh Jaipur Museum Society, patronized by the royal family of Jaipur has been encouraging and patronizing the local arts and knowledge creation with a global outlook, aiming to create a platform for performers, artists and intellectuals from the world over. Sukhnidhey Films, founded by Rituraj Devaang Jain, an Engineer turned Filmmaker, is an award winning media production organization dedicated to the conservation of our rich heritage through powerful films sensitizing the masses, especially the youth.