A Case Study of Addax Bioenergy Sierra Leone Ltd (ABSL)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Bumbuna Hydroelectric

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Ministry of Energy and Power Public Disclosure Authorized Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project Environmental Impact Assessment Draft Final Report - Appendices Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized in association with BMT Cordah Ltd Appendices Document Orientation The present EIA report is split into three separate but closely related documents as follows: Volume1 – Executive Summary Volume 2 – Main Report Volume 3 – Appendices This document is Volume 3 – Appendices. Nippon Koei UK, BMT Cordah and Environmental Foundation for Africa i Appendices Glossary of Acronyms AD Anno Domini AfDB African Development Bank AIDS Auto-Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care BCC Behavioural Change Communication BHP Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project BWMA Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand BP Bank Procedure (World Bank) CBD Convention on Biodiversity CHC Community Health Centre CHO Community Health Officer CHP Community Health Post CLC Community Liaison Committee COD Chemical Oxygen Demand dbh diameter at breast height DFID Department for International Development (UK) DHMT District Health Management Team DOC Dissolved Organic Carbon DRP Dam Review Panel DUC Dams Under Construction EA Environmental Assessment ECA Export Credit Agency EFA Environmental Foundation for Africa EHS Environment, Health and Safety EHSO Environment, Health and Safety Officer EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA -

Letter to African Minerals Limited and Response

HUMAN RIGHTS WHOSE DEVELOPMENT? Human Rights Abuses in Sierra Leone’s Mining Boom WATCH Whose Development? Human Rights Abuses in Sierra Leone’s Mining Boom Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1067 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2014 978-1-62313-1067 Whose Development? Human Rights Abuses in Sierra Leone’s Mining Boom Map of Sierra Leone ............................................................................................................ i Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

U N I T E D N a T I O

U N I T E D N A T I O N S Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs SIERRA LEONE HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT SEPTEMBER 2003 KEY EVENTS district. A concern raised in Kono is that none of the Watsan implementing partners had the facilities or machines for testing water • Yellow Fever outbreak samples. This has been reported to the MOHS. • Security Council extends UNAMSIL’s mandate • UN Agencies and GoSL celebrate World Peace Day SECURITY HIGHLIGHTS • Nigerian lawmakers call on UNAMSIL Overall security UNAMSIL (United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone) reports the overall security situation in HUMANITARIAN HIGHLIGHTS the country to be calm. However there have been some concerns about security along the Yellow Fever outbreak border regions, particularly along the Mano The Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS) River Union Bridge in the south. Similarly the has reported a total of 90 cases of Yellow Sierra Leone Police (SLP) are concerned Fever, from eight districts in the country: about the porous nature of the border in the Tonkolili, Bombali, Kenema, Koinadugu, Port Kamakwie, Tambakha and Koinadugu areas, Loko, Kambia and Kono. Of the 90 reported in the Northern Province that have resulted in cases (as of 29 September) four laboratory increased smuggling of goods across the cases were confirmed, all from the Tonkolili borders. The police have also reported hunters District, where majority of the suspected cases from Guinea, coming across, poaching and emanate from. Earlier, the MOHS gave out crossing back into Guinea. 100,000 doses of vaccine in four chiefdoms in the district. They have now finally secured UNAMSIL’s mandate extended funds to carry out mass immunization The UN Security Council has extended campaign in the remaining seven chiefdoms of UNAMSIL’s mandate, which was to expire on the district. -

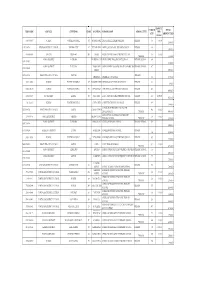

Payment of Tuition Fees to Primary Schools in Tonkolili District for Second Term 2019/2020 School Year

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN TONKOLILI DISTRICT FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR Amount No. EMIS Name Of School District Chiefdom Address Headcount Total to School Per Child Tonkolili 1 250301202 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Dansogoia Bumbuna 521 10000 5,210,000 District Tonkolili Yoni 2 251106203 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Konta 1 206 10000 2,060,000 District Mamaila Tonkolili Kunike- Maconteh- 3 250602211 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School 267 10000 2,670,000 District Sanda Thama Tonkolili Kholifa- 4 251101234 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Magburaka 301 10000 3,010,000 District Rowalla Tonkolili Yoni- 5 251106212 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Mile 91 320 10000 3,200,000 District Mamaila Tonkolili Yoni 6 251104215 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Romano 206 10000 2,060,000 District Mabanta Tonkolili Yoni 7 251101215 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Ronurie 362 10000 3,620,000 District Mamaila Tonkolili Yoni 8 251103216 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Roruks 305 10000 3,050,000 District Mabanta Tonkolili Kunike 9 250601219 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Rosint 204 10000 2,040,000 District Fulawusu Tonkolili Kunike Royeama 10 250601220 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School 202 10000 2,020,000 District Fulawusu Sembu Tonkolili 11 250103213 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Yele Yele 400 10000 4,000,000 District Tonkolili Kunike- 12 250603208 Ahmadiyya Nusrat Jahan Primary School Masingbi 312 10000 3,120,000 District Sanda Tonkolili 13 250302204 Ahmadiyya Primary School Dansogoia Sasakala 105 10000 1,050,000 District -

Sierra Leone

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : SIERRA LEONE Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 22 February, 2002) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 799 07 00 Fax: + 41 22 799 07 01 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 10 BACKGROUND TO THE CONFLICT 10 CHRONOLOGY OF SIGNIFICANT EVENTS SINCE INDEPENDENCE (1961 - 2000) 10 HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS OF CONFLICT (1991-1998) 14 CONTINUED CONFLICT DESPITE THE SIGNING OF THE LOME PEACE AGREEMENT (JULY 1999-MAY 2000) 17 PEACE PROCESS DERAILED AS SECURITY SITUATION WORSENED DRAMATICALLY IN MAY 2000 19 RELATIVELY STABLE SECURITY SITUATION SINCE SIGNING OF CEASE-FIRE AGREEMENT IN ABUJA ON 10 NOVEMBER 2000 21 UN SECURITY COUNCIL EXTENDS BAN ON "CONFLICT DIAMONDS" FROM JANUARY 2002 23 SECURITY IMPROVES WITH FULL DEPLOYMENT OF UNAMSIL AND THE COMPLETION OF DISARMAMENT BY JANUARY 2002 24 MAIN CAUSES OF DISPLACEMENT 24 COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT CAUSED BY MORE THAN NINE YEARS OF WIDESPREAD CONFLICT- RELATED HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES (1991- 2000) 24 MAJOR NEW DISPLACEMENT AFTER BREAK DOWN OF THE PEACE PROCESS IN MAY 2000 25 NEW -

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June). -

Sierra Leone

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : SIERRA LEONE Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 7 July, 2001) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 788 80 85 Fax: + 41 22 788 80 86 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 10 ACCESS TO UN HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORTS 10 HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORTS BY THE UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS (22 DECEMBER 2000 – 16 JUNE 2001) 10 MAIN CAUSES FOR DISPLACEMENT 10 COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT CAUSED BY MORE THAN NINE YEARS OF WIDESPREAD CONFLICT- RELATED HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES (1991- 2000) 10 MAJOR NEW DISPLACEMENT AFTER BREAK DOWN OF THE PEACE PROCESS IN MAY 2000 12 NEW DISPLACEMENT AS CONFLICT EXTENDED ACROSS THE GUINEA-SIERRA LEONE BORDER (SEPTEMBER 2000 – MAY 2001) 15 BACKGROUND OF THE CONFLICT 18 HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS OF CONFLICT (1991-1998) 18 ESCALATED CONFLICT DURING FIRST HALF OF 1999 CAUSED SUBSTANTIAL DISPLACEMENT 21 CONTINUED CONFLICT DESPITE THE SIGNING OF THE LOME PEACE AGREEMENT (JULY 1999-MAY 2000) 22 PEACE PROCESS DERAILED AS SECURITY SITUATION WORSENED DRAMATICALLY IN MAY 2000 25 -

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

Sierra Leone Recovery Strategy for Newly Accessible Areas

Sierra Leone Recovery Strategy for Newly Accessible Areas National Recovery Committee May 2002 Table of Contents GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................ 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 6 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 12 1.1. The National Recovery Structure........................................................................... 12 1.2. A bottom-up approach emphasising local consultations ....................................... 12 1.3. A recovery strategy to promote stability................................................................ 13 2. RESTORATION OF CIVIL AUTHORITY................................................................. 14 2.1. District Administration .......................................................................................... 15 2.2. District Councils .................................................................................................... 16 2.3. Sierra Leone Police................................................................................................ 17 2.4. Courts..................................................................................................................... 19 2.5. Prisons.................................................................................................................... 20 2.6. Paramount Chiefs and Chiefdom -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: 3 1844-SL Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED IDA PARTIAL RISK GUARANTEE IN SUPPORT OF A LOAN IN AN AMOUNT OF UP TO US$38 MILLION IN PRINCIPAL GRANTED BY A COMMERCIAL BANK TO BUMBUNA HYDROELECTRIC COMPANY LIMITED AND Public Disclosure Authorized A PROPOSED IDA GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR8.3 MILLION (US$12.5 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF SIERRA LEONE FOR THE COMPLETION OF THE BUMBUNA HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT UNDER A PUBLIC-PFWATE PARTNERSHIP (“PPP”) Public Disclosure Authorized MAY 20,2005 Energy Group Project Finance and Guarantees InfrastructureDepartment InfrastructureEconomics and Finance Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance oftheir official duties. Its content may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Exchange Rate Effective: April 30, 2005 Currency Unit = Leone (SLL) SLL2835 = US$1 US$1.51209 = SDR1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AfDB African Development Bank BCA Bumbuna Conservation Area BHC Bumbuna Hydropower Company BHP Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project BOT Build-Operate-Transfer BWMA Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority BWMP Bumbuna Watershed Management Plan CAP Communication Action Plan CAS Country Assistance Strategy CDD Community-Driven Development CDM Clean Development Mechanism CFB Carbon Finance Business CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment -

Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone Bumbuna

HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF SIERRA LEONE BUMBUNA INQUIRY REPORT 2012 REPORT OF THE PUBLIC INQUIRY INTO ALLEGED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BUMBUNA, TONKOLILI DISTRICT IN RELATION TO THE EVENTS OF 16TH , 17TH AND 18TH APRIL, 2012 BUMBUNA INQUIRY REPORT 2012 Report of the Public Inquiry into Alleged Human Rights Violations in Bumbuna, Tonkolili District in Relation to the Events of 16TH, 17TH and 18TH April, 2012, in accordance with Section 7 (2) (a) of the Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone Act, 2004 and Section 42 of the Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone (Complaint, Investigations and Inquiries) Rules, 2008 The Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone is an independent institution established by the Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone Act (No. 9), 2004 with the mandate to protect and promote human rights nationwide. Contacts: Headquarters: NEC Building, OAU Drive, Tower Hill, Freetown Southern Region: 1 Old Railway Line, Bo Northern Region: 30 Wallace Johnson Street, Makeni Eastern Region: C/o UNIPSIL Office, UNHCR Compound, 111 Hangha Road, Kenema Web Site: www.hrcsl.org Phone: +232 76 603194 Email: [email protected] The Bumbuna Inquiry Photo Gallery: http://www.flickr.com/photos/hrcsl Online Newsletter: http://hrcsl-newsletter.blogspot.com/2012/09/overview-of-public-inquiry-into-alleged.html ii Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone 24th September, 2012 H.E. Dr. Ernest Bai Koroma President of the Republic of Sierra Leone State House Tower Hill Freetown Your Excellency, RE: REPORT OF THE PUBLIC INQUIRY INTO ALLEGED GROSS VIOLATIONS OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN BUMBUNA, TONKOLI DISTRICT I hereby submit to you, the report of the Public Inquiry into Alleged Gross Violations of Human Rights in Bumbuna, Tonkolili district, in relation to the events of 16th, 17th and 18th April, 2012, conducted by the Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone (HRCSL) from 1st June – 30th September, 2012, as a special report.