Bulletin 4 – Spring 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Österreichische Eisenstraße

Die Österreichische Eisenstraße als UNESCO-Weltkultur- und Naturerbe? Die Österreichische Eisenstraße als UNESCO-Weltkultur-Die Österreichische Eisenstraße und Naturerbe? Ergebnisse einer Machbarkeitsstudie erstellt von Michael S. Falser Ausschnitt aus der Scheda‘schen Generalkarte des Österreichischen Kaiserstaates, um 1850 ISBN 978-3-9501577-5-8 Nationalpark Kalkalpen, Michael S. Falser Schriftenreihe des Nationalpark Kalkalpen Band 9 Impressum © Nationalpark O.ö. Kalkalpen Ges.m.b.H., 2009 Titelfoto Verein O.ö. EIsenstraße, Einklinker v.o.: Archiv Ennskraft, Verein O.ö. Eisenstraße, Michael S. Falser (2x), Erich Mayrhofer Autor Michael S. Falser Redaktion Erich Mayrhofer, Michael Falser, Franz Sieghartsleitner Lektorat Regina Buchriegler, Michael Falser, Franz Sieghartsleitner, Angelika Stückler Fotos Archiv Ennskraft, Michael Falser, Erich Mayrhofer, Nationalpark Kalkalpen, Franz Siegharts- leitner, Verein O.ö. Eisenstraße, Alfred Zisser Quellennachweis Michael S. Falser: Die Österreichische Eisenstraße als UNESCO-Weltkultur- und Naturerbe, Wien 2009 Herausgeber Nationalpark O.ö. Kalkalpen Ges.m.b.H., Nationalpark Allee 1, 4591 Molln Grafik Andreas Mayr Druck Friedrich VDV, Linz; 1. Auflage 3/2009 ISBN 978-3-9501577-5-8 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Danksagung des Autors ........................................................................................................................... 5 Landeshauptmann Niederösterreich ....................................................................................................... 6 Landeshauptmann -

Bergslagen-Sweden) Summary Report Workshop/06 (Bergslagen-Sweden) Summary Report

ECOMUSEUMS: WHAT’S NEXT? WORKSHOP/06 (BERGSLAGEN-SWEDEN) SUMMARY REPORT WORKSHOP/06 (BERGSLAGEN-SWEDEN) SUMMARY REPORT Before the Swedish meeting: the Long network project. The general purpose of the Long network project was to create an effective environment for good practices exchange among European ecomuseums. The idea was that ecomuseums could play the role of a bridge, connecting the many sustainable development best practices experienced in Europe, support the growth of local districts based on a strong sense of place, and concur in local leadership building. Therefore, the trail we have followed is based on the networks, both locally and at a larger scale. Networks are not only mere organisational schemes. At a certain scale they produce new opportunities and ideas and make collective knowledge growth and evolve. To be observers in the processes and not merely of the processes is crucial in order to understand this kind of cultural phenomena. The steps: • 2004: harmonisation of our approaches and goals in the Sardagna- Trento workshop/04 • 2004/05: task-forces to try to make ideas circulate (fine tuning of ideas). Learning journeys set up at a national level (in Sweden, Italy, Poland) and internationally, between Italy and Sweden. • 2005: report on 2004/05 activities and making of new working groups in the Argenta workshop/05. Once agreed methods and goals, the new aim is to produce something together (main fields: training, travelling exhibition, communication, evaluation schemes, database). • 2005/06: good job for training and exhibition groups, less for communication and evaluation schemes. A scheme for a database is produced and is presently on a trial period. -

Establishment and Solidification

Communication and Exploration Foreword Human communities have always been fascinated by the past, using the information gained from elders, the landscape, ancient sites and objects to plan for the future. More or less consciously, innovation is often based on the knowledge we have inherited from earlier genera- tions. Such knowledge is not only a variety of technical skills and tradi- tional savoir-faire, but also a range of behaviours: uses and reciprocities, covenants and unwritten rules, mutual exchanges and informal rela- tionships that can be defined as “social capital”. These assets may be regarded as trivial, and may even be disregarded when things work well, but can be an important resource in a crisis. The central role which heritage can play in order to enhance and pre- serve this particular kind of wealth is increasingly recognised. Today’s public policies value heritage and culture, they are no longer simply regarded as resources used only for entertainment. Ecomuseum policies and practices, which embody both cultural and local development initiatives, are a prominent example of this new trend. Some thirty years after the first ecomuseum projects were initiated, they now operate in every corner of the world. Some indication of the strength of the ecomuseum movement was demonstrated at the Com- munication and Exploration Conference held in Guizhou, China. More than a hundred scholars and practitioners from fifteen countries on the five continents met in 2005 to talk together and share ideas and ex- periences. The themes discussed indicated the very real challenges facing contemporary society, and highlighted the connections between history, memory and innovation. -

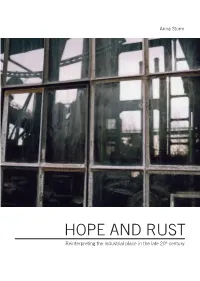

Hope and Rust

Anna Storm Anna Storm In the late 20th century, many Western cities and towns entered a process of de-industrialisation. What happened to the industrial places that were left behind in the course of this transformation? How were they understood and used? Who engaged in their future? What were the visions and what was achieved? Hope and Rust: Reinterpreting the industrial place in the late 20th century examines the conversion of the redundant industrial built environment, into apartments, offi ces, heritage sites, stages for artistic installations, and destinations for cultural tourism. Through a wide-ranging analysis, comprising the former industrial areas of Koppardalen in Avesta, Sweden, the Ironbridge Gorge Museum in Britain, and Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord in the Ruhr district of Germany, a new way of comprehending this signifi cant phenomenon is unveiled. The study shows how the industrial place was turned into a commodity in a complex gentrifi cation process. Key actors, such as companies and former workers, heritage and planning professionals, as well as artists and urban explorers, were involved in articulating values of beauty, authenticity and adventure. By downplaying the dark and diffi cult aspects associated with industry, it became possible to showcase rust from the past fuelled with hope for a better future. Anna Storm is affi liated with the Division of History of Science and Technology at the Royal Institute of Technology, KTH, in Stockholm, Sweden. In 2006, she received the Joan Cahalin Robinson Prize for best-presented -

Jonas Lie Paints the Panama Canal, by Kirsten of Trinec with a Big, Dark Steel Mill Rising Above the River Bank

NUMBER 77 3rd quarter, 2017 CONTENTS REPORT • The Cocheras de Cuatro Caminos: endangered origins of Madrid’s metro, Álvaro Bonet WORLDWIDE • Early Railways Research, David Gwyn and Neil Cossons • At Risk: Negrelli-Hall Railway Freight Shed, Berthold Burckhardt, Massimo Preite and Günter Dinhobl • The ‘Solvent Belge’ Factory Collection, Freddy Joris • The First Welded Commercial Vessel, M/S Carolinian, Zachary Liollio • The Mele Paper Museum, Alessandra Brignola • Remote Sensing Techniques for Industrial Moskoks coke plant in Moscow, not really known even for many locals. What we see here is the Archaeologists, Iain Stuart very short moment after the hot coke was pushed out and the worker is cleaning the chamber for • Heritage Criteria for the Global Water Industry, James further filling. Photo: Viktor Macha Douet MUSEUMS OF INDUSTRY OPINION • Sally Macdonald, director of the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester DOCUMENTING THE UGLINESS EDUCATION AND TRAINING Viktor Macha • Institute for Industrial Archaeology, History of Science and Technology, Helmuth Albrecht It was some time in the late 90s when I found out that heavy industry would • Understanding Industrial Assets inevitably become part of my life. I was 15 years old and my parents took me to the Beskydy mountains in Central Europe for our summer holidays. PUBLICATIONS RECEIVED Thanks to road works and detours we suddenly ended up in the Czech town • Oh Panama! Jonas Lie Paints the Panama Canal, by Kirsten of Trinec with a big, dark steel mill rising above the river bank. Even though I M. Jensen and Bartholomew F. Bland, reviewed by Betsy hadn´t the slightest idea what this rusty monster was, I knew from the very Fahlman first moment that this was it. -

The UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural

The Agricultural Landscape of Southern Öland The medieval land division and land use of the agricultural landscape of southern Öland is unique. Its important values The UNESCO Convention concerning lie in the early historical landscape with linear villages, fields and pastures. The limestone bedrock and grazing animals the Protection of the World Cultural have created the conditions for the important biological val ues of the Great Alvar and the island’s wetlands. This prop and Natural Heritage erty was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2000. The justification of the World Heritage Committee was: What do the Grand Canyon, the Galapagos Islands, the Cita unesco’s World Heritage List of Summer 2011 includes 911 del on Haiti and the Engelsberg Factory have in common? properties in 151 countries. The landscape of Southern Öland takes its contemporary form from its long cultural history, adapting to the physical constraints They all are defined by unesco as treasures of our common Fourteen Swedish sites, considered by unesco’s as having of the geology and topography. Southern Öland is an outstanding world heritage. They are the unique evidence of the history outstanding universal values, currently are included in the exam ple of human settlement, making the optimum use of diverse of the earth and humankind. The unesco World Heritage World Heritage List. The Naval Port of Karlskrona landscape types on a single island. Convention for the protection of the world’s cultural and na Sweden was elected to unesco’s World Heritage Committee tural heritage was established at the un general conference in The need for a naval base in southern Sweden grew in in Oktober 2007. -

Bergslagen-Sweden) Summary Report Workshop/06 (Bergslagen-Sweden) Summary Report

ECOMUSEUMS: WHAT’S NEXT? WORKSHOP/06 (BERGSLAGEN-SWEDEN) SUMMARY REPORT WORKSHOP/06 (BERGSLAGEN-SWEDEN) SUMMARY REPORT Before the Swedish meeting: the Long network project. The general purpose of the Long network project was to promote the ecomuseum as a mean to empower people, allowing them to take care of their places and of the local heritage –something which is often out of the reach of traditional museums- and helping them to provide visions for a a sustainable future. The trail we have followed is based on the networks, both locally and at a larger scale. Networks are not only mere organisational schemes. At a certain scale they produce new opportunities and ideas and make collective knowledge growth and evolve. So the features of the network and the way it works and evolves is not a simple detail, on the contrary it is central in our project. The steps: • 2004: harmonisation of our approaches and goals in the Sardagna- Trento workshop/04 • 2004/05: task-forces to try to make ideas circulate (fine tuning of ideas) • 2005: report on 2004/05 activities and making of new working groups in the Argenta workshop/05. Once agreed methods and goals, the new aim is to produce something together (main fields: training, travelling exhibition, communication, evaluation schemes, database). • 2005/06: good job for trainig and exhibition groups, less for communication and evaluation schemes. A scheme for a database is produced and is presently on a trial period. A question arises about a possible more formal organisation for the network. National workshops held in Italy and Poland before the one in Sweden. -

Rooted in Sweden

rooted in Sweden No 5 * January 2008 The SwedGen Road Tour 2007PAGE 2 Visit Ellis Island SwedGen Road Tour 2007 in Cambridge, Minnesota. From left: Olof Cronberg, Anna- PAGE 5 Lena Hultman, Anneli Andersson, Kathy Meade (Genline), and Charlotte Börjesson Visit Allen County We found the Swedish roots Public Library PAGE 7 In May 2007 a group of four Swedish genealogists went on the Swedgen Road Tour visiting Minneapolis and Cambridge, Minnesota; Rockford, Illinois and Jamestown, New York. The Digital At lectures and workshops, we showed how to find your Swedish roots. The possibilites to solve the research problems have improved in just a few years. We Race were able to help almost all attenders to the meetings. However, one important PAGE 10 lesson is that it isn’t enough to have access to the sources and to the databases. You need to know how to search the databases in order to find interesting matches. You also need to know how to interpret the result. We saw cases were The Iron researchers had followed the wrong track due to misinterpretation of the result. Industry in In this issue we will try to give some ideas how to do and how to avoid pitfalls. Sweden PAGE 13 Thank you for helping us We would like to say thank you to all the local organizing committees who help us with ar- ranging the workshops, to all the families that let us stay in your homes and to our sponsors, the DIS Society and Genline. The SwedGen Road Tour group. Newsletter of the DIS Society Computer Genealogy Society of SwedenJanuary 2008 • rootedwww.dis.se in Sweden no 5 | 1 SwedGen Road Tour 2007 After a year of planning, in the end Illinois, New York and Pennsylvania. -

Adaptation of Post-Industrial Areas As Hydrological Windows to Improve the City’S Microclimate

energies Article Adaptation of Post-Industrial Areas as Hydrological Windows to Improve the City’s Microclimate Rafał Blazy * , Hanna Hrehorowicz-Gaber and Alicja Hrehorowicz-Nowak Department of Spatial Planning, Urban and Rural Design, Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology, 31-155 Cracow, Poland; [email protected] (H.H.-G.); [email protected] (A.H.-N.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-12-628-20-50 Abstract: Post-industrial areas in larger cities often cease to fulfill their role and their natural result is their transformation. They often constitute a large area directly adjacent to the city structure and are exposed to urbanization pressure, and on the other hand, they are often potential hydrological windows. The approach to the development strategy for such areas should take this potential into account. The article presents the example of Cracow (Poland) and post-industrial areas constituting the hydrological and bioretention potential in terms of the possibility of their development and the legal aspects of the development strategies of these areas. Keywords: post-industrial areas; spatial planning; bioretention; urban microclimate Citation: Blazy, R.; 1. Introduction Hrehorowicz-Gaber, H.; The world is becoming more and more urbanized, with larger, denser conglomerates Hrehorowicz-Nowak, A. Adaptation of buildings. Compact cities are perceived as more energy-efficient and resource-efficient, of Post-Industrial Areas as but they have an influence on the intensification of microclimatic effects. Areas of thermally Hydrological Windows to Improve massive, impermeable surfaces, typical of dense urban centers, store heat, distorting the City’s Microclimate. Energies 2021, the diurnal temperature cycle, increasing surface water runoff, increasing the risk of 14, 4488.