Love's Pilgrimage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpacas Orgling Mp3, Flac, Wma

L.E.O. Alpacas Orgling mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Alpacas Orgling Country: US Released: 2006 Style: Alternative Rock, Power Pop, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1267 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1788 mb WMA version RAR size: 1127 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 156 Other Formats: MP3 XM MP2 VOX MIDI DTS AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Overture 1 0:33 Written-By, Strings, Acoustic Guitar – Maclaine Diemer Goodbye Innocence Bass – Chris Z. Electric Guitar – John FieldsMellotron – Maclaine DiemerSlide Guitar – Tony 2 3:51 GoddessWritten-By, Vocals – Andy SturmerWritten-By, Vocals, Acoustic Guitar, Drums, Keyboards, Mellotron – Bleu Ya Had Me Goin' 3 Backing Vocals – Matt MahaffeyBass, Clavinet – John FieldsDrums – Steve GormanGuitar – 3:10 Maclaine DiemerWritten-By, Vocals, Electric Guitar, Keyboards – Bleu Distracted Cello – David Bentley Lyrics By – Alex ScutroStrings, Arranged By – Paula KelleyViolin – 4 4:18 Angie ShyrWritten-By, Lyrics By, Vocals, Acoustic Guitar, Drums, Keyboards – Bleu Written-By, Vocals – Mike Viola Make Me Acoustic Guitar – Chris Holmes , Derek Webb, Isaac Hanson, Jay LashleyBacking Vocals – 5 Jason ScheffBacking Vocals, Drums – Ducky CarlisleBass – John FieldsWritten-By, Backing 3:00 Vocals, Electric Guitar, Vocoder, Acoustic Guitar – Bleu Written-By, Vocals, Acoustic Guitar – Mike Viola The Ol' College Try Cello – David Bentley Electric Guitar – John FieldsViolin – Angie ShyrVocals, Arranged By, 6 3:43 Strings – Paula KelleyWritten-By, Bass – Tony GoddessWritten-By, Vocals, Piano, Drums, Keyboards -

Mozart's Die Zauberflöte: a Kingdom of Notes and Numbers

MOZART’S DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE: A KINGDOM OF NOTES AND NUMBERS by Daemon Garafallo A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Daemon Garafallo ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express his thanks to his committee members for their guidance, especially to his thesis advisor, Dr. Ken Keaton, for helping the author through a difficult time these past few years, and to Dr. Sandra McClain for going above and beyond in her dual role of committee member and academic advisor and for doing an excellent job at both. He also would like to acknowledge Dr. James Cunningham for his help and guidance throughout his degree. iv ABSTRACT Author: Daemon Garafallo Title: Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte: A Kingdom of Notes and Numbers Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Ken Keaton Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2016 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed Die Zauberflöte in the last year of his life. It was intended in part to glorify Freemasonry as a new Emperor, more hostile to the Masons, took his office. After a brief survey of his life and works, this paper shows how Mozart used number symbolism in the opera, and will equip the reader with an understanding of this as practiced by the Freemasons. Further, it will show how Mozart associated the characters of the opera with specific musical tones. It will expose a deeper understanding of the question of meaning in word and text in his opera. -

Icons of Elegance Dancing Is Easy Mp3, Flac, Wma

Icons Of Elegance Dancing Is Easy mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Dancing Is Easy Country: Finland Released: 2004 MP3 version RAR size: 1677 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1562 mb WMA version RAR size: 1557 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 733 Other Formats: XM APE DMF AC3 WMA APE ASF Tracklist Hide Credits Dancing Is Easy Backing Vocals – Antti IkolaBacking Vocals, Bass, Bass [6-String Bass] – Anssi*Drums, 1 Tambourine – Harri*Electric Piano [Wurlitzer], Musical Box, Glockenspiel – Catherine KontzVocals, Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Synth – Henri* Sandra Lee Backing Vocals, Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Synth – Henri*Drums – Harri*Electric Piano 2 [Rhodes], Organ [Hammond] – Antti*Vocals, Bass, Piano, Mandolin [Electric Mandolin], Keyboards – Anssi* Running To Catch Up With Myself Acoustic Guitar – Antti*Backing Vocals, Bass, Vibraphone, Bass [6-String Bass] – Anssi*Drums – 3 Harri*Electric Piano [Wurlitzer] – Catherine*Trombone, Trombone [Bass Trombone], Euphonium – Mikko MustonenVocals, Electric Guitar, Slide Guitar, Guitar [Nashville Guitar], Dulcitone – Henri* Local Library Backing Vocals, Acoustic Guitar, Mandolin [Electric Mandolin] – Henri*Drums – Harri*Electric 4 Piano [Rhodes] – Antti*Vocals, Bass, Guitar [Nashville Guitar], Strings [String Machine], Piano – Anssi* Lead Me Away Acoustic Guitar – Riku RajamaaDrums – Harri*Electric Piano [Rhodes] – Antti*Harmony Vocals, 5 Bass – Anssi*Organ [Hammond] – Pekka GröhnPedal Steel Guitar – Olli HaavistoVocals, Electric Guitar – Henri* Ready When You Are 6 -

EJ Full Draft**

Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy By Edward Lee Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfacation of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair Professor James Q. Davies Professor Ian Duncan Professor Nicholas Mathew Summer 2020 Abstract Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy by Edward Lee Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair This dissertation emerged out of an archival study of Italian opera libretti published between 1800 and 1835. Many of these libretti, in contrast to their eighteenth- century counterparts, contain lengthy historical introductions, extended scenic descriptions, anthropological footnotes, and even bibliographies, all of which suggest that many operas depended on the absorption of a printed text to inflect or supplement the spectacle onstage. This dissertation thus explores how literature— and, specifically, the act of reading—shaped the composition and early reception of works by Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and their contemporaries. Rather than offering a straightforward comparative study between literary and musical texts, the various chapters track the often elusive ways that literature and music commingle in the consumption of opera by exploring a series of modes through which Italians engaged with their national past. In doing so, the dissertation follows recent, anthropologically inspired studies that have focused on spectatorship, embodiment, and attention. But while these chapters attempt to reconstruct the perceptive filters that educated classes would have brought to the opera, they also reject the historicist fantasy that spectator experience can ever be recovered, arguing instead that great rewards can be found in a sympathetic hearing of music as it appears to us today. -

SPONS AGENCY AVAILABLE from DOCUMENT RESUME Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 216 480 EC 142 431 TITLE Arts for the Gifted and Talented: Grades One Through Six. INSTITUTION California State Dept. of Education, Sacramento. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 81 NOTE 88p. AVAILABLE FROMCalifornia State Department of Education, Publications Sales, P.O. Box 271, Sacramento, CA 95802 ($2.75 each, California residents add sales tax). EDRS PRICE, MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Art Education; Cognitive Development; Dance; Drama; Elementary Education; *Gifted; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Lesson Plans; Music; Poetry; *Talent; Visual Arts IDENTIFIERS *California\-- ABSTRACT The booklet presents California guidelines for arts education of gifted students in Grades 1 through 6. An introductory section examines the relevance of cognitive domain factors (knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation) to the :arts. The second section presents 12 sample lesson plans in creative movement and dance, 12 in music, 6 in creative dramatics, 7 in poetry, and 12 in visual arts. Section 3 details interdisciplinary activities blending drama, movement, dance, language arts, social studies, science, and the visual arts. A glossary of approximately 120 terms ilsed in visual arts,.music, drama, poetry, and dance is also included. (CL) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS aro the best that can be made from the original document. *******'**************************************************************** -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 56,1936-1937

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephone, Ticket and Administration Offices, Com. 149s FIFTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1936-1937 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra INCORPORATED SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes By John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1937, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, IllC. The OFFICERS and TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Bentley W. Warren .... President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Ernest B. Dane . Treasurer Allston Burr M. A. De Wolfe Howe Henry B. Cabot Roger I. Lee Ernest B. Dane Richard C. Paine Alvan T. Fuller Henry B. Sawyer N. Penrose Hallowell Edward A. Taft Bentley W. Warren G. E. Judd, Manager C. W. Spalding, Assistant Manager [729] . Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON The principal business of this company is: 1 Investment of funds and management of property for living persons. 2. Carrying out the provisions of the last will and testament of deceased persons. Our officers would welcome a chance to dis- cuss with you either form of service. zAllied with The First National Bank a/' Boston [730] SYMPHONIANA Serge Prokofieff The Pushkin Centenary SERGE PROKOFIEFF The accompanying head of Serge Prokofieff is reproduced from the origi- nal drawing by Alexandre Iacofleff which • Considering the rarity of old French porcelain apothecary jars, its not likeiy that lamps made of them will become common. Any reproduction would be obvious, as the texture of the old porcelain gives these pieces their charm. The inscriptions are of course all different, and the coloring of the decorations is varied There is one to be had in black and white. -

Anthropocene Modernisms: Ecological Expressions of The

ANTHROPOCENE MODERNISMS: ECOLOGICAL EXPRESSIONS OF THE “HUMAN AGE” IN ELIOT, WILLIAMS, TOOMER, AND WOOLF A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Rebekah A. Taylor May 2016 Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials i Dissertation written by Rebekah A. Taylor B.A., Augusta State University, 2007 M.A., Middle Tennessee State University, 2010 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by _____________________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Kevin Floyd _____________________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Ryan Hediger ___________________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Tammy Clewell ___________________________________ Emariana Widner ___________________________________ Deborah Barnbaum Accepted by ____________________________________, Chair, Department of English Robert Trogdon ____________________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences James L. Blank ii TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………………...iii LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………………v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………..vii CHAPTERS I. Introduction to Anthropocene Modernisms ………………………………………………1 Early Twentieth Century Formulations of “Anthropocene”……………..10 The Environmental Tradition and the Role of Literary Criticism……….19 Defining Modernist Form(s) / Aesthetic(s)………………………………30 The Example of Water…………………………………………………...39 Preview of Chapters……………………………………………………...44 -

The Spoken Text CD 1 1 Leopold Mozart: Sinfonia Di Caccia No

The Spoken Text CD 1 1 Leopold Mozart: Sinfonia di caccia No, there's nothing wrong, either with your equipment or your ears (those barking dogs are part of the score); and no, that music isn't by Mozart. By a Mozart, yes; but if he hadn't been the father of the Mozart, the chances are that most of us would never have heard of him. And though he was a man with a high opinion of himself, that wouldn't have surprised him in the least. He never expected immortality. Leopold Mozart was an intelligent and cultured man, a very respectable composer, a fine violinist, and the author of an influential treatise on playing the violin. For a musician of his time – middle of the eighteenth century – he was exceptionally well educated. Headed originally for the priesthood, he studied logic and jurisprudence at the University of Salzburg in Austria, and it was there that he spent the whole of his professional life as a court and church musician in the service of the Prince-Archbishop. Well I say 'all' of it – in fact there were some years that he spent away from the court, carting his two prodigiously gifted children around Europe, and making a pot of money in the process. His daughter Maria Anna was a child virtuoso on the harpsichord and fortepiano , and an excellent singer, and his son Wolfgang was quite simply the most staggering prodigy in the history of music. At the age of three he was picking out pleasing combinations of notes on the harpsichord, and by the time he was four he could already play a number of short pieces from memory – and faultlessly. -

Before, During, and After 18Th Century Baroque and Program Notes

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2020 PASSACAGLIA AND ITS RELATED FORMS: BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER 18TH CENTURY BAROQUE AND PROGRAM NOTES Austin Han University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2619-2659 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.383 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Han, Austin, "PASSACAGLIA AND ITS RELATED FORMS: BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER 18TH CENTURY BAROQUE AND PROGRAM NOTES" (2020). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 167. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/167 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

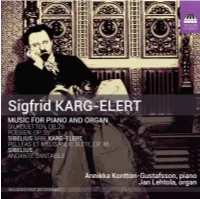

TOCC0419DIGIBKLT.Pdf

PIANO, ORGAN, HARMONIUM: THREE INSTRUMENTS, THREE SONORITIES, ONE TECHNIQUE by Annikka Konttori-Gustafsson and Jan Lehtola Te works recorded on this album are rather rare, having been composed or transcribed for the unusual combination of piano and harmonium. Why should a composer opt to bring two very diferent keyboard instruments together as a duo? Te answer can be found by taking a closer look at the co-existence of piano, organ and harmonium. Te technique required to play each of them did not difer enormously in the Romantic era, and in the nineteenth century in particular students were taught to play the organ in the same way as they were the piano. Te reason may lie in the fact that many of the major composers of organ music of the time, such as Brahms, Franck, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Saint-Saëns and Schumann, were also frst-class pianists. Te piano infuenced not only organists’ technique but organ-building as a whole. Te works of these pianist- composers posed new challenges in the organ lof, and various aids were devised to make playing organs as efortless as playing the piano: the organ keys, for example, were enlarged until they soon resembled those of the piano. Te Romantic era also fostered interest in the harmonium; it was an inexpensive instrument and added variety to music-making in the home. Easy to carry about and capable of producing a range of timbres, it also enjoyed a career as a concert instrument that, though brief, was rich in repertoire. Many important composers wrote for it, among them Berlioz, Boëllmann, Dvořák, Franck, Karg-Elert, Vierne and Widor. -

Visual Art Exhibitions and State Identity in the Late Cold War

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Worlds on View: Visual Art Exhibitions and State Identity in the Late Cold War A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Nicole Murphy Holland Committee in charge: Professor John C. Welchman, Chair Professor Norman Bryson Professor Robert Edelman Professor Grant Kester Professor Kuiyi Shen 2010 © Nicole Murphy Holland, 2010 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Nicole Murphy Holland is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii This dissertation is dedicated to my beloved family, Lindsay, Emily, and Peter Holland, whose unswerving support and devotion has made this project possible. iv I didn’t know at the time that John Wayne was an American icon. I thought the painting was just another picture of a cowboy. Vladimir Mironenko, commenting on the painting John Wayne by Annette Lemieux. v Table of Contents Signature Page……………………………………………………………………… iii Dedication ……………………………………………………………………………iv Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………………v Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………… vi Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………… viii Vita…………………………………………………………………………………… x Abstract………………………………………………………………………………xii Introduction……………………………………………………………………………1 Part 1: Theoretical Underpinnings………………………………………… 12 Part 2: Exhibition Functions……………………………………………… 18 Part 3: The Nature of Exhibition Space…………………………………… -

Maryland Community Band Nextnow Fest.Pdf

Maryland Community Band M B Bill Sturgis, Conductor C THE MARYLAND COMMUNITY BAND Piccolo Bass Clarinet Horn Heidi Sweely Phaedra McNair Dan LaRusso PRESENTS David Wagner Ronald Olexy Flute Sandra Roberts Virginia Forstall Alto Saxophone Adam Watson Elvira Freeman Cynthia Alston On The Move Mary Kate Gentile Caroline Cherrix Trombone Katie Janota Eirik Cooper David Buckingham Kelly Pasciuto Daniel Epps Kevin Corbin Bill Sturgis, Conductor Sara Short Sarah Flinspach Darrell Greenlee Jennifer Somerwitz Jack Frankel Lisa Hines Linda Wagner Deborah Weiner Marianne Kassabian Kathleen Wilson Abby Rose Tenor Saxophone Bob Schmertz Oboe Tim Brown Julie Ponting Keith Hill Euphonium Andrea Schewe Tom Jackson Baritone Saxophone Bassoon Dan Purnell Tuba Tom Cherrix Patrick FitzGerald Kristi Engel Trumpet Dorothy Lee Dale Allen Billy Snow Bb Clarinet McNeal Anderson Susan Ahmad Ernest Bennett Percussion Edgar Butt LeAnn Cabe Beth Bienvenu Helen Butt Craig Carignan Lori Dominick Jim Coppess Joe Dvorsky Rachel Hickson Lisa Fetsko Tim Girdler Alan Sactor Jeri Holloway Tom Gleason Matt Testa Alice LaRusso Larry Kent Chad McCall Richard Liska Stanley Potter Boris Lloyd Angela Pulin Doug McElrath Dana Robinson Rick Pasciuto Saturday, September 8 | 7:00 PM Ken Rubin Amy Schneider Dekelboum Concert Hall Karen Trebilcock Robert Wynne The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center The Maryland Community Band was founded as an outreach program of the University of Maryland School of Music in 1995. For more information about the band, please visit us at www.marylandcommunityband.org Cover photo: Dancers perform to traditional Basque music at the Smithsonian Folklife 2018 Festival on July 10, 2016. – C. Carignan PROGRAM NOTES Amparito Roca was composed by Spanish musician and composer Jaime Texidor (1884– 1957) who named it after one of his piano students, then 12-year-old Amparito Roca.