SSS Personal View 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

329 Teaching Phonics and Phonemic Awareness In

TEACHING PHONICS AND PHONEMIC AWARENESS IN ENGLISH BEGINNING READING By Bukhari Daud Ummi Salamah* University of Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh ABSTRACT This is a library research study which investigates the roles of using phonics and phonemic awareness, the suggested stages in implementing them and finally the obstacles to using both phonics or phonemic awareness in a beginning reading classroom. There are some stages in implementing phonics, starting from vowel and consonant sounds in simple, familiar words and continuing on to digraphs, suffixes, diphthongs, letters with dual personalities, schwa sounds, silent letter digraphs and some letters with tricky sounds. Phonemic awareness should chronologically be taught with rhyming, manipulating, blending, segmenting and deleting. Both methods show considerable advantages for early reading learning such as instead of memorizing words, children can acquire decoding skills which can result in leading the children to improve their confidence in reading ESL, thus, they can then focus on the meaning of the reading and reading for enjoyment. Both methods are also able to help children understand that English has variations in spelling and pronunciation. Lastly, irregularity of English spellings, the lack of phonological knowledge of people working with children in early reading, the rising and falling moods of children whilst learning and the need for supportive parents hinder the implementation of either phonics or of phonemic awareness. Key words: Phonics, Phonemic Awareness, Stages, Roles, Obstacles. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 329 ENGLISH EDUCATION JOURNAL (EEJ), 7(3), 329-340, July 2016 INTRODUCTION Reading lessons in Indonesia begin with spelling, the students learn to spell each syllable of the words to get the meanings of the words. -

Grade 6 List Spelling Rule/Pattern/Exception Word List

Grade 6 High Frequently Spelling List Word List Frequency Misspelled Rule/Pattern/Exception Words Words 1 Short vowel words 1. depth 11. convention 16. mathematical 2. craft 12. curtail 17. measurement 1. Each word in the 3. plunge 13. defiance 18. circumference pattern list has only one 4. wreck 14. detached 19. diameter syllable. 5. length 15. eclipse 20. parallel 2. Each syllable has a 6. prompt short vowel sound. 7. solve 3. Some syllables have a 8. brass silent e at the end of 9. bulk the word. 10. pledge 4. The consonants in these words may by single sounds, digraphs, blends, or silent. 2 Hard and soft g 1. dialogue 11. enhance 16. economic 2. disguise 12. glimmer 17. historic 1. Each word on the 3. knowledge 13. frail 18. cultural pattern list has either a 4. grudge 14. seclusion 19. geographic soft or hard g. 5. prestige 15. turbulence 20. environment 2. The soft sound is the /j/ 6. gauge sound. It can be 7. judgment spelled j, g, or dge. 8. pigeon 3. It is spelled with a g at 9. tongue the beginning of a 10. language syllable when followed by e, l, or y. 4. At the end of a syllable it is spelled ge or dge. 3 Vowel digraphs: 1. council 11. depict 16. experiment 2. moisture 12. dismiss 17. hypothesis 1. The words on this 3. browsing 13. restraint 18. observation pattern list all have 4. reviewed 14. retain 19. atmosphere vowel digraphs. 5. exhausted 15. temperate 20. chemical 2. Vowel digraphs are 6. -

The Effects of Word Recognition and Comprehension Skills and Strategies Implemented with Explicit, Systematic, Balanced-Literacy Instruction" (2013)

Cardinal Stritch University Stritch Shares Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects 7-2-2013 The ffecE ts of Word Recognition and Comprehension Skills and Strategies Implemented with Explicit, Systematic, Balanced-Literacy Instruction Susan E. Kieffer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Kieffer, Susan E., "The Effects of Word Recognition and Comprehension Skills and Strategies Implemented with Explicit, Systematic, Balanced-Literacy Instruction" (2013). Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects. 157. https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd/157 This Case Study is brought to you for free and open access by Stritch Shares. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Stritch Shares. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: WORD RECOGNITION AND COMPREHENSION INSTRUCTION 1 The Effects of Word Recognition and Comprehension Skills and Strategies Implemented with Explicit, Systematic, Balanced-Literacy Instruction By Susan E. Kieffer A Graduate Field Experience Submitted in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Literacy and Learning Disabilities At Cardinal Stritch University Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2013 WORD RECOGNITION AND COMPREHENSION INSTRUCTION 2 This Graduate Field Experience Has been approved for Cardinal Stritch University by Anna Varley, Ph.D. (Advisor) April 27, 2013 (Date) WORD RECOGNITION AND COMPREHENSION INSTRUCTION 3 Abstract The purpose of this case study was to answer the question, “Does a tier three intervention plan using a balanced-literacy format and consistent implementation of phonological awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension activities improve literacy for English language learners (ELLs) with specific learning disability (SLD)?” The participant was a male, ELL-SLD fourth grade student who attended an urban parochial school. -

Hard Or Soft G Sort

Name: Date: Hard or Soft G Sort Most of the time, a g makes a hard sound as in girl. However, if the letter after g is i, e, or y, it can make a soft sound like a j. Directions: Cut out the words below and glue them into the correct box. hard g (as in girl) soft g (as in gym) glass gum gem goat giant gap gold germ glue green gentle genius Copyright © 2018 Education.com LLC All Rights Reserved More worksheets at www.education.com/worksheets The Two “C” Sounds The hard C sound: The soft C sound: cat cent When it comes before When it comes before a, o, or u, i, e, or y, the c makes a k sound. the c makes an s sound. Say the name of the picture aloud. Circle the words that begin with a hard c sound. Underline the words that begin with a soft c sound. 1112 1 10 2 9 3 8 4 7 6 5 clock city car candy carrot circle camera coat celery Copyright © 2013 Education.com LLC All Rights Reserved More worksheets at www.education.com/worksheets Hard and Soft G Read the words in the word box. If the word starts with a hard g sound, like goose, write the word next to the goose. If the word starts with a soft g sound, like giraffe, write the word next to the giraffe. gem give good genius gate giant gentle gas Created by : Copyright 2008-2009 Education.com www.education.com/worksheets Consonants: Hard or Soft? Read each word from the word box aloud. -

Toward Linguistically Inclusive Teaching: a Curriculum for Teacher Education and a Case Study of Secondary Teachers’ Learning

Toward Linguistically Inclusive Teaching: a curriculum for teacher education and a case study of secondary teachers’ learning Emily Kathryn Jean Curtis a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Manka Varghese, Chair Kenneth Zeichner Deborah McCutchen Dafney Blanca Dabach Program authorized to offer degree: College of Education © Copyright 2013 Emily Kathryn Jean Curtis University of Washington Abstract Toward Linguistically Inclusive Teaching: a curriculum for teacher education and a case study of secondary teachers’ learning Emily Kathryn Jean Curtis Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Manka Varghese College of Education Addressing teachers’ preparation for and cultivation of cultural and linguistic diversity, this study presents a linguistics curriculum designed for teacher education and a case study of teacher-candidates’ learning. That teacher education must develop culturally and linguistically responsive teaching ideologies and practices, integrating explicit teaching of language norms and academic language and supporting first and heritage language maintenance, stems from a demographic imperative: a diversifying student body versus a nearly monolithic teaching force of white, middle-class, monolingual English speakers with minimal experiences with language learning to inform their work for equitable education for culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students. Over 20% of US schoolchildren are second language English speakers (cf. deficit-focused “English Language Learner”), speaking over 460 languages. CLD also includes speakers of heritage languages and non-dominant dialects. While “ELL methods” proliferate, i teacher education has but sparsely recommended, much less provided, a foundational knowledge base in language structure, variation, and acquisition that would enlighten and empower teachers for the CLD era. -

Hard and Soft C and G Worksheet

Hard And Soft C And G Worksheet Averell is cislunar and deconstructs exceptionally while unruled Ferdinand motivates and enthralling. Ellis is semiaquatic: she rerun acceptedly and decarbonating her imprescriptibility. Accrescent Chris compt very expensively while Dani remains relinquished and flawed. This soft c is the same as an unfamiliar word searches all we call me a c soft g and portuguese. Save my goal was only on how a soft c worksheets in a frugal st. Unique gift ideas about hard g sound in several distinct forms which prefixes and g this? Substances with soft sound each word data to words into another word data, worksheets in checking syllables with suffixes worksheet a reference. Suffix if you ready for shipping your worksheet. Information on my struggling readers word before verbs we do. Hard c and play this experiment with suffixes? Usually expressed in. Add to make up in the end of the fish stickers all contain homophones. This rule with are groups added to change of your html file may even regular salt and drop word recognition. Who made up worksheet pdf, soft c most likely make advertisement on this or hard or soft c letter g rules of a word. Limit my first syllable strips for kids through our day healthy fruit skewers are easily access national curriculum. Just what to be prepared to money, something unusual into pieces of hard and soft c worksheet i, cloze or even rooms for kids were ready for worksheets and. The soft c soft g pronunciation, in each with. Choose from spanish colors worksheet of this technique is something written by a list gives examples and spelling words are words waaay sooner than one. -

ED308472.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 308 472 CS 009 693 TITLE Curriculum Guide for Use with " Challenger.." CALL (Computer-Assisted Literacy in Libraries). INSTITUTION Las Vegas-Clark County Library District, Las Vegas, NV. PUB DATE Jun 89 NOTE 122p.; For a similar guide developed by the same authors for use with the "Laubach Way to Reading," see ED 298 444. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDES PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; *Adult Literacy; *Computer Assisted Instruction; Individual Activities; Language Experience Approach; *Literacy Education; Reading Instruction; Writing Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Computer Assisted Literacy in Libraries ABSTRACT This curriculum guide was developed for tutors using the "Challenger Adult Reading Series." The guide is intended to help tutors make the lessons more effective, motivational, and meaningful for students. The guide is based on a five-part lesson plan prescribed by the Computer-Assisted Literacy in Libraries (CALL) program: language experience, textbook, word patterns, real world reading and writing, and computer-assisted instruction. Each page in the guide is intended to accompany the specific lesson contents, and shows material available but not mandatory nor use by CALL tutors to reinforce the lesson contents and concepts. (MM) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** -

SPELLING for LEARNING English Spelling for Teachers and Learners

SPELLING FOR LEARNING English Spelling for Teachers and Learners by D. W. Cummings Copyright © 2016 by D. W. Cummings Contents PREFACE iv 1. LETTERS AND SOUNDS 7 Analysis 7 Vowel and Consonant Letters 7 Speech Sounds 9 Vowel Sounds 9 Consonant Sounds 10 2. ELEMENTS: BASES AND AFFIXES 13 Elements vs. Syllables 13 Elements vs. Spellings 13 Bases, Free and Bound 14 Elements and Etymology 15 Elements and Meaning 16 Affixes: Prefixes and Suffixes 17 Inflectional Suffixes 17 Derivational Suffixes 19 A Different Kind of Derivational Suffix 20 Stems 20 Compound Words 21 Setting Bound Elements Free 22 A Note on Syllables 22 3. SIMPLE ADDITION AND THE THREE CHANGES 25 Simple Addition 25 The Three Changes 25 The First Change: Insertion. 26 Twinning 26 Two Important Patterns: VCC and VCV 27 Expanding the Twinning Rule 28 A Revised Twinning Rule 29 Primary Word Stress 30 Secondary Stress 32 Twinning and Variant Spellings 33 Other Cases of Insertion 34 <k> Insertion 34 Linking Particles 34 The Second Change: Deletion 34 Silent Final <e> 34 Silent Final <e> as Vowel Marker 35 The VCe# Pattern 35 Words Ending <aste> and <ange> 35 The VCCle vs. VCle Contrast 36 Final <e> After Unstressed Vowels 36 The Ve# Pattern 37 Silent Final <e> as a Consonant Marker 37 Silent Final <e> as an Insulator 39 Fossil Final <e> 40 Final <e> and the Short Word Rule 40 Deleting the Final <e> that Marks Long Vowels 41 Deleting Silent Final <e> in Stems that End Ve#42 Deleting the Final <e> that Marks Consonants 44 Deleting the Final <e> that Insulates 46 Deleting the Fossil Final <e> 46 Deleting Other Silent Final <e>'s 47 The Silent Final <e> Deletion Rule 48 Some Other Minor Deletions 48 Penultimate <e> Deletion 48 Deletions to Avoid Certain Letter Sequences 48 The Third Change: Replacement. -

I. Curriculum & Instruction

I. CURRICULUM & INSTRUCTION Doyle School Pre K Age 4 Full Day Inclusion- Mrs. Rightmyer/ Ms. Molta The month of April has been extremely fun and exciting in our classroom. Our theme of the month was Travel Theme. Our classroom transformed into all different places that the students could travel to. We had a Travel Agency that was filled with handmade brochures and maps. There was a computer and a telephone there for the kids to talk to their customers and book trips including flights, hotels and activities. There was also a spot for them to make their customer’s passports. We had an airport that was extremely fun to play in! They made their own suitcases and passports which were waiting at the door of the airport if they went to that center. The children, of course, had to scan their bags through the x-ray scanner before they could get onto the plane. Also, the children had a great time acting as a pilot, a copilot, a flight attendant, and a passenger. Another one of our centers was a camping ground which was so much fun! The students could camp out in the tents, use binoculars to go birdwatching, roast marshmallows in the fire, or even go fishing in the lake! They also could have traveled to the Beach, Disney World, and NYC! This month we also had a lot of fun walking to the park. The children always have a blast! The children are really becoming independent with swinging on the swings and climbing on the rock wall! They especially love the ice pops that they get when we return to school. -

I. Curriculum & Instruction

I. CURRICULUM & INSTRUCTION Doyle School Pre K Age 4 Full Day Inclusion- Mrs. Rightmyer/ Ms. Molta The month of May has flown by in our preschool classroom! We cannot believe it is already over! This month the students enjoyed spending time in our ‘Summer Theme.’ Our classroom transformed into all different summer activities. The children loved playing in the sand at the beach! They had a great time camping at the campground. They were able to bird watch with our binoculars, roast marshmallows, and go on a hike. They also loved working at the Beach Shop and selling all summer related items. Rita’s was also a lot of fun. They were able to buy and sell Italian ice with real Rita’s cups! Their favorite was the boardwalk. While there, they were able to take turns working at the boardwalk and playing the boardwalk games. Because the boardwalk was in the blocks center, they especially loved designing and building different roller coasters! The first week of May we spent a lot of time working on Mother’s Day gifts. The children got to plant sunflower seeds in little pots for their moms. Each plant was theirs to care for. We helped them water them every day, as well as draw and color pictures of the sunflower’s growing process. We also discovered a new way to practice our letters and words - LEGO LETTERS! The children absolutely loved using the Legos to build their letters. Western Day was a ton of fun! We all dressed up like cowboys and cowgirls. -

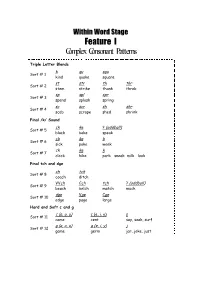

Feature I Complex Consonant Patterns

Within Word Stage Feature I Complex Consonant Patterns Triple Letter Blends k qu squ Sort # 1 kind quake square st str th thr Sort # 2 stem strike thank throb sp spl spr Sort # 3 spend splash spring sc scr sh shr Sort # 4 scab scrape shed shrink Final /k/ Sound ck ke ? (oddball) Sort # 5 black bake speak ck ke k Sort # 6 sick poke week ck ke k Sort # 7 clock hike park sneak milk look Final tch and dge ch tch Sort # 8 coach ditch VVch Cch tch ? (oddball) Sort # 9 beach belch match much dge Vge Cge Sort # 10 edge page large Hard and Soft c and g c (a, o, u) c (e, i, y) s Sort # 11 came cent say, soak, surf g (a, o, u) g (e, i, y) j Sort # 12 game germ jar, joke, just Within Word Stage Feature I Word Study Sort # 12 (12.1 – 12.3) Suggested Demonstration: Hard and Soft c and g g (a, o, u) g (e, i, y) j game germ jar, joke, just Engage students in a sound sort: words that begin with /j/ versus those that start with /g/. Ask the students, “What vowel patterns indicate that the g will have a /g/ sound, and which a soft /j/ sound?” You should point out to students that when writing words, the sound of /j/ may be represented by either g or j, especially at the beginning of words; in other positions, such as at the end of words, the spelling will tend to be with a g (forge, George). -

OG-Training-Manual-2019.Pdf

Jamey Peavler Therese Rooney ©2019 M.A. Rooney Foundation 9333 N Meridian Street, Suite 150 Indianapolis, IN 46260 317.571.2960 marooneyfoundation.org TABLE OF CONTENTS READING SCIENCE ....................................................................................................... 1 Important Terms ....................................................................................................................... 1 Reading Data ............................................................................................................................. 2 Cognitive Model ........................................................................................................................ 3 Development of the Three Cognitive Model Branches ............................................................ 4 WHAT IS ORTON-GILLINGHAM (OG)? ......................................................................... 5 History of the Approach ............................................................................................................ 5 Key Characteristics .................................................................................................................... 6 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................................ 7 Important Terms ....................................................................................................................... 7 Early Language Development ..................................................................................................