Dispute Between the “Usurper” and His Commons: the Long Parliament of 1406

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Political Poems Ca. 1640

Studies in English Volume 1 Article 13 1960 Notes on Political Poems ca. 1640 Charles L. Hamilton University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Hamilton, Charles L. (1960) "Notes on Political Poems ca. 1640," Studies in English: Vol. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol1/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hamilton: Notes on Political Poems Notes on Political Poems, c. 1640 Charles L. Hamilton HET CIVILwars in England and Scotland during the seventeenth century produced a wealth of popular literature. Some of it has permanent literary merit, but a large share of the popular creations, especially of the poetry, was little more than bad doggerel. Even so, one little-known and two unpublished poems such as the following are important as a guide to public opinion. From the period of the Bishops’ Wars (1638-40) the Scottish Covenanters repeatedly urged the English to abolish episcopacy and to enter a religious union with them.1 The following poem, written very likely on the eve of the meeting of the Long Parliament, exem plifies the Scottish feeling very clearly: Oyes, Oyes do I Cry The Bishops’ Bridles Will ye Buy2 Since Bishops first began to ride, In state so near the crown They have been aye puffed up with pride And ride with great renown. -

Part I Background and Summary

PART I BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY Chapter 1 BRITISH STATUTES IN IDSTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The North American plantations were not the earliest over seas possessions of the English Crown; neither were they the first to be treated as separate political entities, distinct from the realm of England. From the time of the Conquest onward, the King of England held -- though not necessarily simultaneously or continuously - a variety of non-English possessions includ ing Normandy, Anjou, the Channel Islands, Wales, Jamaica, Scotland, the Carolinas, New-York, the Barbadoes. These hold ings were not a part of the Kingdom of England but were govern ed by the King of England. During the early medieval period the King would issue such orders for each part of his realm as he saw fit. Even as he tended to confer more and more with the officers of the royal household and with the great lords of England - the group which eventually evolved into the Council out of which came Parliament - with reference to matters re lating to England, he did likewise with matters relating to his non-English possessions.1 Each part of the King's realm had its own peculiar laws and customs, as did the several counties of England. The middle ages thrived on diversity and while the King's writ was acknowledged eventually to run throughout England, there was little effort to eliminate such local practices as did not impinge upon the power of the Crown. The same was true for the non-Eng lish lands. An order for one jurisdictional entity typically was limited to that entity alone; uniformity among the several parts of the King's realm was not considered sufficiently important to overturn existing laws and customs. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early M

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 © Copyright by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia by Sara Victoria Torres Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Christine Chism, Co-chair Professor Lowell Gallagher, Co-chair My dissertation, “Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia,” traces the legacy of dynastic internationalism in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and early-seventeenth centuries. I argue that the situated tactics of courtly literature use genealogical and geographical paradigms to redefine national sovereignty. Before the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, before the divorce trials of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon in the 1530s, a rich and complex network of dynastic, economic, and political alliances existed between medieval England and the Iberian kingdoms. The marriages of John of Gaunt’s two daughters to the Castilian and Portuguese kings created a legacy of Anglo-Iberian cultural exchange ii that is evident in the literature and manuscript culture of both England and Iberia. Because England, Castile, and Portugal all saw the rise of new dynastic lines at the end of the fourteenth century, the subsequent literature produced at their courts is preoccupied with issues of genealogy, just rule, and political consent. Dynastic foundation narratives compensate for the uncertainties of succession by evoking the longue durée of national histories—of Trojan diaspora narratives, of Roman rule, of apostolic foundation—and situating them within universalizing historical modes. -

In Shakespeare’S 2 Henry IV Line Cottegnies

“What trust is in these times?” Thinking the Secular State with “the colour of religion” in Shakespeare’s 2 Henry IV Line Cottegnies To cite this version: Line Cottegnies. “What trust is in these times?” Thinking the Secular State with “the colour of religion” in Shakespeare’s 2 Henry IV. Etudes Anglaises, Klincksieck, In press, ”Religion and Drama: Shakespeare and his Contemporaries”, 71 (4), pp.409-423. hal-01996199v1 HAL Id: hal-01996199 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01996199v1 Submitted on 28 Jan 2019 (v1), last revised 11 Feb 2019 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Etudes Anglaises, "Religion and Drama: Shakespeare and his Contemporaries", 71.4 (2018): 409-423. Line COTTEGNIES “What trust is in these times?” Thinking the Secular State with “the colour of religion” in Shakespeare’s 2 Henry IV This article focuses on the idea, repeatedly reasserted in the second tetralogy, of the impossibility of refounding trust in the political order after the initial “sin” of the deposition of Richard II by Bolingbroke—trust being defined in Georg Simmel’s sense as as the possibility of investing in a future that can be expected to be the continuation of the present. -

British House of Commons (1810) MUNUC 33 ONLINE 1 British House of Commons (1810) | MUNUC 33 Online

British House of Commons (1810) MUNUC 33 ONLINE 1 British House of Commons (1810) | MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ LETTER FROM THE CRISIS DIRECTOR…………………………………………..3 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR………………………………………………………. 5 COMMITTEE OVERVIEW………………………………………………………..7 HISTORY OF BRITAIN………………………………………………..………… 9 STATEMNT OF THE PROBLEM………………………………………..……….. 23 BLOC POSITIONS…………………..………………………………..……….. 30 APPENDIX…………………………………………..…………………………..31 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………….. 34 2 British House of Commons (1810) | MUNUC 33 Online LETTER FROM THE CRISIS DIRECTOR ____________________________________________________ Welcome, Colleagues! Welcome to the heady days of the British House of Commons! My name is Thadeus Obora, and I will be serving as your Crisis Director. I am a fourth-year student and a History/Political Science double major in the college, with a great love for all things Industrial Revolution and historical. I hail from Naperville, in the suburbs of Chicago (Neuqua Valley HS) and love the opportunity I have now to finally live in Chicago. As somebody who almost went to MUNUC when I was in high school, I relish the opportunity to participate in the behind-the-scenes antics that make this conference run well - so much so that after being an Assistant Chair on the Cuba 1960 committee my first year, Chair on the German Unification committee by second year, and the Japan 1960 committee last year, I have returned as an executive! When not frantically working on the background guide for this committee, I can be found exploring the city for new restaurants and foodie-locales, browsing eBay, or repairing vintage fountain pens and typewriters - an archaic hobby that I use to finance all of the binge-eating. -

Year 7 History Project

Year 7 History Project Middle Ages - Power and Protest Session 1: King Edward I • In the following slides you will find information relating to: • Edward and parliament • Edward and Wales • Edward and the War of Independence Edward I • Edward facts • Edward was born in 1239 • In 1264 Edward was held prisoner when English barons rebelled against his father Henry III. • In 1271 Edward joined a Christian Crusade to try and free Jerusalem from Muslim control • Edward took the throne in 1272. • Edward fought a long campaign to conquer Wales • Edward built lots of castles in Wales such as Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech castles • Edward had two nicknames - 'Longshanks' because he was so tall and the 'Hammer of the Scots' for obvious reasons • Edward’s war with Scotland eventually brought about his death when he died from sickness in 1307 when marching towards the Scottish Border. Llywelyn Ap Gruffudd • In 1275 Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales refused to pay homage (respect) to King Edward I of England as he believed himself ruler of Wales after fighting his own uncles for the right. • This sparked a war that would result in the end of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (the last) who was killed fighting the English in 1282 after several years of on off warfare. • Edward I destroyed the armies of Llywelyn when they revolted against England trying to take complete control of Wales. • As a result Llywelyn is known as the last native ruler of Wales. • After his death Edward I took his head from his body and placed it on a spike in London to deter future revolts. -

Joan Plantagenet: the Fair Maid of Kent by Susan W

RICE UNIVERSITY JOAN PLANTAGANET THE FAIR MAID OF KENT by Susan W. Powell A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts Thesis Director's Signature: Houston, Texas April, 1973 ABSTRACT Joan Plantagenet: The Fair Maid of Kent by Susan W. Powell Joan plantagenet, Known as the Fair Maid of Kent, was born in 1328. She grew to be one of the most beautiful and influential women of her age, Princess of Wales by her third marriage and mother of King Richard II. The study of her life sheds new light on the role of an intelligent woman in late fourteenth century England and may reveal some new insights into the early regnal years of her son. There are several aspects of Joan of Kent's life which are of interest. The first chapter will consist of a biographical sketch to document the known facts of a life which spanned fifty-seven years of one of the most vivid periods in English history. Joan of Kent's marital history has been the subject of historical confusion and debate. The sources of that confusion will be discussed, the facts clarified, and a hypothesis suggested as to the motivations behind the apparent actions of the personages involved. There has been speculation that it was Joan of Kent's garter for which the Order of the Garter was named. This theory was first advanced by Selden and has persisted in this century in the articles of Margaret Galway. It has been accepted by May McKisack and other modern historians. -

Deschamps, Brinton, Langland, and the Hundred Years'

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2016 ‘But Who Will Bell the Cat?’: Deschamps, Brinton, Langland, and the Hundred Years’ War Elizaveta Strakhov Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Yearbook of Langland Studies, Vol. 30 (2016): 253-276. DOI. © 2016 Brepols Publishers. Used with permission. ‘But Who Will Bell the Cat?’: Deschamps, Brinton, Langland, and the Hundred Years War Elizaveta Strakhov Surprisingly little work has been done on William Langland and contemporary responses to the Hundred Years War: surprising not in the least because this war was a dominant international political conflict over the course of the poet’s lifetime and because Langland openly references the famous Treaty of Brétigny in the continuation of the Meed episode in Passus III. In that passus, Meed invokes the Treaty as part of her defense of meed, and its centrality to good administrative rule, before the king at Westminster. She accuses Conscience of having demurred from battle for fear of a ‘dym cloude’ (B. 3. 193), which has been understood as a topical allusion to the so-called ‘Black Monday’ storm that beset Edward III’s troops at Chartres on April 13, 1360, just before the signing of the Treaty of Brétigny, much remarked upon by contemporary chroniclers.1 Meed goes on to accuse Conscience of having persuaded the king ‘to leven his lordshipe for a litel silver’ (B. 3. 207) and, far more unambiguously in the C-text, of having counseled him ‘to leten | In his enemyes handes his heritage of Fraunce’ (C. -

British Royal Ancestry Book 6, Kings of England from King Alfred the Great to Present Time

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY BRITISH ROYAL ANCESTRY, BOOK 6 Kings of England INTRODUCTION The British ancestry is very much a patchwork of various beginnings. Until King Alfred the Great established England various Kings ruled separate parts. In most cases the initial ruler came from the mainland. That time of the history is shrouded in myths, which turn into legends and subsequent into history. Alfred the Great (849-901) was a very learned man and studied all available past history and especially biblical information. He came up with the concept that he was the 72nd generation descendant of Adam and Eve. Moreover he was a 17th generation descendant of Woden (Odin). Proponents of one theory claim that he was the descendant of Noah’s son Sem (Shem) because he claimed to descend from Sceaf, a marooned man who came to Britain on a boat after a flood. (See the Biblical Ancestry and Early Mythology Ancestry books). The book British Mythical Royal Ancestry from King Brutus shows the mythical kings including Shakespeare’s King Lair. The lineages are from a common ancestor, Priam King of Troy. His one daughter Troana leads to us via Sceaf, the descendants from his other daughter Creusa lead to the British linage. No attempt has been made to connect these rulers with the historical ones. Before Alfred the Great formed a unified England several Royal Houses ruled the various parts. Not all of them have any clear lineages to the present times, i.e. our ancestors, but some do. I have collected information which shows these. They include; British Royal Ancestry Book 1, Legendary Kings from Brutus of Troy to including King Leir. -

The Medieval Parliament

THE MEDIEVAL PARLIAMENT General 4006. Allen, John. "History of the English legislature." Edinburgh Review 35 (March-July 1821): 1-43. [Attributed in the Wellesley Index; a review of the "Reports on the Dignity of a Peer".] 4007. Arnold, Morris S. "Statutes as judgments: the natural law theory of parliamentary activities in medieval England." University of Pennsylvania Law Review 126 (1977-78): 329-43. 4008. Barraclough, G. "Law and legislation in medieval England." Law Quarterly Review 56 (1940): 75-92. 4009. Bemont, Charles. "La séparation du Parlement anglais en deux Chambres." In Actes du premier Congrès National des Historiens Français. Paris 20-23 Avril 1927, edited by Comite Français des Sciences Historiques: 33-35. Paris: Éditions Rieder, 1928. 4010. Betham, William. Dignities, feudal and parliamentary, and the constitutional legislature of the United Kingdom: the nature and functions of the Aula Regis, the Magna Concilia and the Communa Concilia of England, and the history of the parliaments of France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, investigated and considered with a view to ascertain the origin, progress, and final establishment of legislative parliaments, and the dignity of a peer, or Lord of Parliament. London: Thomas and William Boone, 1830. xx, 379p. [A study of the early history of the Parliaments of England, Ireland and Scotland, with special emphasis on the peerage; Vol. I only published.] 4011. Bodet, Gerald P. Early English parliaments: high courts, royal councils, or representative assemblies? Problems in European civilization. Boston, Mass.: Heath, 1967. xx,107p. [A collection of extracts from leading historians.] 4012. Boutmy, E. "La formation du Parlement en Angleterre." Revue des Deux Mondes 68 (March-April 1885): 82-126. -

A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3

Factsheet G3 House of Commons Information Office General Series A Brief Chronology of the August 2010 House of Commons Contents Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 2 15th and 16th centuries 3 Treason, revolution and the Bill of Rights: This factsheet has been archived so the content The 17th Century 4 The Act of Settlement to the Great Reform and web links may be out of date. Please visit Bill: 1700-1832 7 our About Parliament pages for current Developments to 1945 9 information. The post-war years: 11 The House of Commons in the 21st Century 13 Contact information 16 Feedback form 17 The following is a selective list of some of the important dates in the history of the development of the House of Commons. Entries marked with a “B” refer to the building only. This Factsheet is also available on the Internet from: http://www.parliament.uk/factsheets August 2010 FS No.G3 Ed 3.3 ISSN 0144-4689 © Parliamentary Copyright (House of Commons) 2010 May be reproduced for purposes of private study or research without permission. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes not permitted. 2 A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3 Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 1097-99 B Westminster Hall built (William Rufus). 1215 Magna Carta sealed by King John at Runnymede. 1254 Sheriffs of counties instructed to send Knights of the Shire to advise the King on finance. 1265 Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned a Parliament in the King’s name to meet at Westminster (20 January to 20 March); it is composed of Bishops, Abbots, Peers, Knights of the Shire and Town Burgesses. -

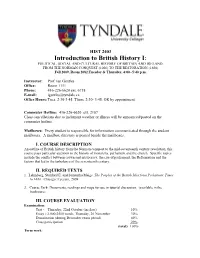

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading.