GUNN-THESIS-2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Royalston Community Newsletter

THE ROYALSTON COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER December 2020 Volume XXII IssueX January 2021 A Publication of the Friends of the Phinehas S. Newton Library, Royalston, Massachusetts Calendar of Events December 1 Monday December 18 Friday National Ugly Sweater Day NORAD follows Santa’s travels this month, and can be seen on-line at http://www.noradsanta.org. This December 21 Monday special mission of the North American Aerospace Defense Predawn Ursid Meteor Shower continues from about a Command at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado goes live week ago, peaking this morning through tomorrow, and depart- December 1, providing information and games to help every- ing shortly after Christmas. The remains of the Tuttle Comet will one gear up for the big night. produce a “shooting star” every six to ten minutes, but there have been bursts of up to 25 in a single hour. December 4 Friday 6 pm South Village Tree Lighting and Gazebo Dedi- 5:02 a.m. Winter Solstice – First Day of Winter (Day- cation sponsored by The Royalston South Village Revital- light hours begin to increase!) ization group. All are welcome. Hot chocolate and cookies. Music provided by Larry Trask and Rene Lake. Memorial December 25 Friday Christmas Day ornaments from the Ladies’ Benevolent Society will be hung on the tree. To get yours, call Laurie Deveneau at 978-249- December 26 Saturday First Day of Kwanzaa 5807. The 120 Drawing will be held and a special guest in a red suit will visit. In case of inclement weather, the event will December 29 Tuesday be held on the following Friday, December 11. -

Strategic Goal 5: Encourage the Pursuit of Appropriate Partnerships with the Emerging Commercial Space Sector

National Aeronautics and Space Administration FFiscaliscal YYeaear 20102010 PERFORMANCEPERFORMANCE ANDAND ACCOUNTABILITYACCOUNTABILITY REPORTREPORT www.nasa.gov NASA’s Performance and Accountability Report The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) produces an annual Performance and Accountability Report (PAR) to share the Agency’s progress toward achieving its Strategic Goals with the American people. In addition to performance information, the PAR also presents the Agency’s fi nancial statements as well as NASA’s management challenges and the plans and efforts to overcome them. NASA’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 PAR satisfi es many U.S. government reporting requirements including the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993, the Chief Financial Offi cers Act of 1990, and the Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996. NASA’s FY 2010 PAR contains the following sections: Management’s Discussion and Analysis The Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section highlights NASA’s overall performance; including pro- grammatic, fi nancial, and management activities. The MD&A includes a description of NASA’s organizational structure and describes the Agency’s performance management system and management controls (i.e., values, policies, and procedures) that help program and fi nancial managers achieve results and safeguard the integrity of NASA’s programs. Detailed Performance The Detailed Performance section provides more in-depth information on NASA’s progress toward achieving mile- stones and goals as defi ned in the Agency’s Strategic Plan and NASA’s FY 2010 Performance Plan Update. It also includes plans for correcting performance measures that NASA did not achieve in FY 2010 and an update on the mea- sures that NASA did not complete in FY 2009. -

The Royalston Community Newsletter

THE ROYALSTON COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER December 2015 Volume XVII, Issue X January 2016 A Publication of the Friends of the Phinehas S. Newton Library, Royalston, Massachusetts Calendar of Events December 2 Wednesday December 31 Thursday New Year’s Eve 6 pm Christmas Tree Lighting at Town Hall. (Library open until 5 pm) song, cheer, cookies, and the guy in the red suit. January 1 Friday Happy 2016! December 4 Friday 7 pm Royalston Open Mic will feature the January 2 Saturday Side Street Band. Good music, good company Earth at Perihelion, the closest pass of our Earth and good food (all on the cheap) at Town Hall. to the Sun, a mere 91,403,891 miles Sponsored by the Cultural Council. January 4 Monday December 6 - 14 Hanukkah Schools re-open 4 pm Friends of the Library meeting. Dis- December 7 Monday cuss library support and this newsletter. 4 pm Friends of the Library meeting. Discuss library support and this newsletter. All welcome. January 5 Tuesday Twelfth Night December 9 Wednesday January 8 Friday 7:30 pm Ladies’ Benevolent Society - 7 pm Open mic: Good music, good packing holiday baskets at the home of Theresa company and good food. .. right in town. Spon- Quinn on the common. Election of next year’s sored by the Cultural Council. officers. All welcome. Please call 249-5993 for more information. 8:31 p.m. New Wolf Moon December 13 Sunday January 11 Monday Geminid Meteor Shower - With clear skies, this 4:30 pm Library book discussion stands to be THE light show of the year as it is group: Easygoing book chat. -

In This Issue

San Diego Cherokee Community Newsletter Issue 30 www.sandiegocherokeecommunity.com November 1, 2011 In this Issue: 1. October 23rd SDCC Community Meeting 2. December 11th SDCC Community Meeting 3. Cherokee Youth Section 4. Upcoming Meetings 5. Cherokee Culture Notes 6. Community News and Announcements 7. Other Local Cherokee Communities News 8. Local Cherokee Library 9. Baker sworn in as Cherokee Nation Principal Chief, Inauguration Nov. 6 10. Year End Donation Drives for Needy Cherokees and Others 11. FYI – Native Themed Activities in Your Backyard 12. Membership registration for 2012 – Don’t forget to re-due. October 23rd SDCC Community Meeting – Fall Get Together with Cherokee Nation Officials Our Oct. 23rd meeting was held at Centro Cultural de la Raza with attendance of over 90 people. The theme of the meeting was our annual get together with Cherokee officials and others from Oklahoma. Unfortunately, many of the officials including the Chief were unable to attend due to the election of the Principal Chief which was recently decided and sworn in a couple of days before our meeting. But there were about 25 people from Oklahoma including Miss Cherokee, the National Choir, crafts people, and others. We had stickball, corn husk doll making, and basketry. Below are some of the pictures of the get together. Mona Oge cooked and Set up preparations prepared the meats with her husband OG. Registration 2 Corn Husk Doll Making and Stickball 3 The Meeting Phil C. conducting Julia Coates and Bill Baker talked on the current issues of the meeting. the nation and their impacts on the community. -

Anales Universidad

REPÚBLICA ORIENTAL DEL URUGUAY ANALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD ENTREGA N? 161 La admisión de un trabajo para ser publicado en estos ANALES, no significa que las autoridades universita rias participen de las doc trinas, juicios y opiniones que en él sostenga su autor. ¡»vf- BIBLIOTECA IMPRESORA L.I.G.U. ^ccÍTAD OE Ot^ CERRITO 740 MONTEVIDEO AÑO 1947 CRÓNICA ANALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD AÑO LVI MONTEVIDEO 1947 ENTREGA N? 161 EL 2? CENTENARIO DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE PRINCETON Una de las Universidades más prestigiosas de América, —la de Princeton— cumplió este año el II Centenario de su fundación. Sus au toridades cursaron invitación a esta Casa de Estudios, para que se hi ciera representar en los actos a realizarse en conmemoración de fecha tan señalada en la historia de ese centro universitario estadounidense. La Universidad de Montevideo atendió preferentemente esa invita ción, y adoptó algunas resoluciones por las cuales pudiera testimoniarse a la institución norteamericana, la satisfacción que provocaba en el seno de este organismo el magno acontecimiento. Dispuso, así, que el Secre tario General Dr. Felipe Gil, durante su permanencia en Estados Unidos, hiciera entrega personal al Presidente de la Universidad de Princeton, de una placa en la que se expresara la sincera, adhesión de nuestra Uni versidad a las celebraciones, Y además delegó su representación en el Dr. José A. Mora Otero, para que estuviera presente, en nombre de la institución, en las ceremonias finales de junio. Los actos celebrados alcanzaron singular relieve; muchas universi dades de todo el mundo estuvieron representadas en ellos y fueron mu chas también las personalidades que recibieron distinciones de la fa mosa Universidad. -

The Cosmological, Ontological, Epistemological, and Ecological Framework of Kogi Environmental Politics

Living the Law of Origin: The Cosmological, Ontological, Epistemological, and Ecological Framework of Kogi Environmental Politics Falk Xué Parra Witte Downing College University of Cambridge August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Anthropology Copyright © Falk Xué Parra Witte 2018 Abstract Living the Law of Origin: The Cosmological, Ontological, Epistemological, and Ecological Framework of Kogi Environmental Politics This project engages with the Kogi, an Amerindian indigenous people from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range in northern Colombia. Kogi leaders have been engaging in a consistent ecological-political activism to protect the Sierra Nevada from environmentally harmful developments. More specifically, they have attempted to raise awareness and understanding among the wider public about why and how these activities are destructive according to their knowledge and relation to the world. The foreign nature of these underlying ontological understandings, statements, and practices, has created difficulties in conveying them to mainstream, scientific society. Furthermore, the pre-determined cosmological foundations of Kogi society, continuously asserted by them, present a problem to anthropology in terms of suitable analytical categories. My work aims to clarify and understand Kogi environmental activism in their own terms, aided by anthropological concepts and “Western” forms of expression. I elucidate and explain how Kogi ecology and public politics are embedded in an old, integrated, and complex way of being, knowing, and perceiving on the Sierra Nevada. I argue that theoretically this task involves taking a realist approach that recognises the Kogi’s cause as intended truth claims of practical environmental relevance. By avoiding constructivist and interpretivist approaches, as well as the recent “ontological pluralism” in anthropology, I seek to do justice to the Kogi’s own essentialist and universalist ontological principles, which also implies following their epistemological rationale. -

American Fluseum of Natural History

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE American fluseum of Natural History. Vol. Vll. SOCIAL ORGANIZATION AND RITUALISTIC CERE- MONIES OF THE BLACKFOOT INDIANS. BY CLARK WISSLER NEW YORK: Published by Order of the Trustees. 1912. CONTENTS OF VOLUME VII. Part I. The Social Life of the Blaokfoot Indians. By Clark Wissler. 1911 1 Part II. Ceremonial Bundles of the Blackfoot Indians. By Clark Wissler. 1912 . 65 Index. By Miss Bella Weitzner . 291 Illustrations. By Miss Ruth B. Howe. lIn fMIDemortam. David C. Duvall died at his home in Browning, Montana, July 10, 1911. He was thirty-three years old. His mother was a Piegan; his father a Canadian-French fur trade employe at Ft. Benton. He was educated at Fort Hall Indian School and returned to the Reservation at Browning, where he maintained a blacksmith shop. The writer first met him in 1903 while collecting among his people. Later, he engaged him as interpreter. Almost from the start he took an unusual interest in the work. He was of an investigating turn of mind and possessed of considerable linguistic ability. On his own initiative he set out to master the more obscure and less used parts of his mother tongue, having, as he often said, formed an ambition to become its most accurate translator into English. As time went on, he began to assist in collecting narratives and statements from the older people. Here his interest and skill grew so that during the last year of his life he contributed several hundred p&vges Qf manuscript. These papers have furnished a considerable part of the data on the Blackfoot so far published by this Museum and offer material for several additional studies. -

TTSIQ #2 Page 1 JANUARY 201

TTSIQ #2 page 1 JANUARY 201 Its all about Earth, re-explored from the vantage point of space, and connecting to our “neighborhood.” NEWS SECTION pp. 3-26 p. 3 Earth Orbit and Mission to Planet Earth - 13 reports p. 8 Cislunar Space and the Moon - 5 reports, 1 article p. 17 Mars and the Asteroids - 6 reports p. 21 Other Planets and Moons - 2 reports p. 23 Starbound - 7 reports ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ARTICLES, ESSAYS & MORE pp. 28-42 - 8 articles & essays (full list on last page) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENTS & TEACHERS pp. 43-58 - 9 articles & essays (full list on last page) This new space suit has many new features, But improvement #1 is that it does away with the traditional airlock See the article on page 5 1 TTSIQ #2 page 2 JANUARY 201 TTSIQ Sponsor Organizations 1. About The National Space Society - http://www.nss.org/ The National Space Society was formed in March, 1987 by the merger of the former L5 Society and National Space institute. NSS has an extensive chapter network in the United States and a number of international chapters in Europe, Asia, and Australia. NSS hosts the annual International Space Development Conference in May each year at varying locations. NSS publishes Ad Astra magazine quarterly. NSS actively tries to influence US Space Policy. About The Moon Society - http://www.moonsociety.org The Moon Society was formed in 2000 and seeks to inspire and involve people everywhere in exploration of the Moon with the establishment of civilian settlements, using local resources through private enterprise both to support themselves and to help alleviate Earth's stubborn energy and environmental problems. -

Lunar Nautics: Designing a Mission to Live and Work on the Moon

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lunar Nautics: Designing a Mission to Live and Work on the Moon An Educator’s Guide for Grades 6–8 Educational Product Educator’s Grades 6–8 & Students EG-2008-09-129-MSFC i ii Lunar Nautics Table of Contents About This Guide . 1 Sample Agendas . 4 Master Supply List . 10 Survivor: SELENE “The Lunar Edition” . 22 The Never Ending Quest . 23 Moon Match . 25 Can We Take it With Us? . 27 Lunar Nautics Trivia Challenge . 29 Lunar Nautics Space Systems, Inc. ................................................. 31 Introduction to Lunar Nautics Space Systems, Inc . 32 The Lunar Nautics Proposal Process . 34 Lunar Nautics Proposal, Design and Budget Notes . 35 Destination Determination . 37 Design a Lunar Lander . .38 Science Instruments . 40 Lunar Exploration Science . 41 Design a Lunar Miner/Rover . 47 Lunar Miner 3-Dimensional Model . 49 Design a Lunar Base . 50 Lunar Base 3-Dimensional Model . 52 Mission Patch Design . 53 Lunar Nautics Presentation . 55 Lunar Exploration . 57 The Moon . 58 Lunar Geology . 59 Mining and Manufacturing on the Moon . 63 Investigate the Geography and Geology of the Moon . 70 Strange New Moon . 72 Digital Imagery . 74 Impact Craters . 76 Lunar Core Sample . 79 Edible Rock Abrasion Tool . 81 i Lunar Missions ..................................................................83 Recap: Apollo . 84 Stepping Stone to Mars . 88 Investigate Lunar Missions . 90 The Pioneer Missions . 92 Edible Pioneer 3 Spacecraft . .96 The Clementine Mission . .98 Edible Clementine Spacecraft . .99 Lunar Rover . 100 Edible Lunar Rover . 101 Lunar Prospector . 103 Edible Lunar Prospector Spacecraft . 107 Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter . 109 Robots Versus Humans . 11. 1 The Definition of a Robot . -

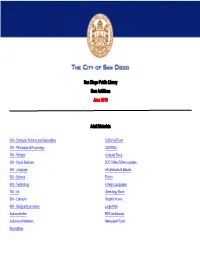

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2010

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2010 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes MP3 Audiobooks Audiovisual Materials Newspaper Room Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title [MYST] FIC/AKUNIN Akunin, B. (Boris) Sister Pelagia and the red cockerel [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Holly blues [MYST] FIC/ALFIERI Alfieri, Annamaria. City of silver [MYST] FIC/ATHERTON Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity down under [MYST] FIC/BANNISTER Bannister, Jo. Liars all [MYST] FIC/BARBIERI Barbieri, Maggie. Final exam [MYST] FIC/BEATON Beaton, M. C. Death of a village [MYST] FIC/BEATON Beaton, M. C. Love, lies and liquor [MYST] FIC/BEATON Beaton, M. C. The perfect paragon [MYST] FIC/BLACK Black, Cara Murder in the Latin Quarter [MYST] FIC/BLACK Black, Cara Murder in the Palais Royal [MYST] FIC/BORG Borg, Todd. Tahoe silence [MYST] FIC/BOX Box, C. J. Blood trail [MYST] FIC/BOX Box, C. J. Nowhere to run [MYST] FIC/BOX Box, C. J. Savage run [MYST] FIC/BRADLEY Bradley, C. Alan The weed that strings the hangman's bag [MYST] FIC/BRAUN Braun, Lilian Jackson. The cat who had 60 whiskers [MYST] FIC/BRAUN Braun, Lilian Jackson. The cat who went bananas [MYST] FIC/BROWN Brown, Rita Mae. Cat of the century [MYST] FIC/CAIN Cain, Chelsea. Evil at heart [MYST] FIC/CARL Carl, Lillian Stewart. -

December 2020 - January 2021

Enriching life in the Big Canoe community December 2020 - January 2021 POA News 3 Events & Happenings 19 Wining & Dining 28 Getting Fit & Healthy 29 Santa greeted a procession Around the Tees 30 of over 400 vehicles filled with Racquets ‘Round the Nets 35 holiday celebrants at the Fire Station during Big Canoe's Marina 36 first "Wilderness Wonderland." Let’s Go Clubbing 40 (Photo by Karen Steinberg) Made in BC Gift Guide 50 Don't just list your home, get it sold. #1 in homes and lots sold www.BigCanoe.com 706.268.3333 [email protected] DECEMBER 2020/JANUARY 2021 INSIDETHEGATES.ORG | 3 POA News Preserving Big Canoe’s Character: The Clubhouse staff to re-emphasize that drink limits will be enforced. Clubhouse Edition Part of my job as general manager is to preserve the character of Big Canoe. This goes beyond making sure By Scott Auer we repaint the Postal Facility or have a fresh layer of pine Big Canoe General Manager needles on the traffic circle to greet inbound visitors. It’s about maintaining standards, regardless of the setting. I We love to highlight all that makes Big Canoe such an know of nu- unbelievable place to live, especially around the holidays. merous prop- Beyond the natural beauty and unmatched amenities are our erty owners employees – those 200+ folks who tirelessly make sure the who say they snow is cleared, the greens are pristine, and the meals come forgo The straight to your table hot from the kitchen. These staffers Clubhouse are too often overlooked and because of the underappreciated. -

Faulkner and the Great Depression: Aesthetics, Ideology, and the Politics of Art

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 Faulkner and the Great Depression: Aesthetics, Ideology, and the Politics of Art. Theodore B. Atkinson III Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Atkinson, Theodore B. III, "Faulkner and the Great Depression: Aesthetics, Ideology, and the Politics of Art." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 262. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/262 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.