University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

Reading 1.2 Caravaggio: the Construction of an Artistic Personality

READING 1.2 CARAVAGGIO: THE CONSTRUCTION OF AN ARTISTIC PERSONALITY David Carrier Source: Carrier, D., 1991. Principles of Art History Writing, University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp.49–79. Copyright ª 1991 by The Pennsylvania State University. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. Compare two accounts of Caravaggio’s personality: Giovanni Bellori’s brief 1672 text and Howard Hibbard’s Caravaggio, published in 1983. Bellori says that Caravaggio, like the ancient sculptor Demetrius, cared more for naturalism than for beauty. Choosing models, not from antique sculpture, but from the passing crowds, he aspired ‘only to the glory of colour.’1 Caravaggio abandoned his early Venetian manner in favor of ‘bold shadows and a great deal of black’ because of ‘his turbulent and contentious nature.’ The artist expressed himself in his work: ‘Caravaggio’s way of working corresponded to his physiognomy and appearance. He had a dark complexion and dark eyes, black hair and eyebrows and this, of course, was reflected in his painting ‘The curse of his too naturalistic style was that ‘soon the value of the beautiful was discounted.’ Some of these claims are hard to take at face value. Surely when Caravaggio composed an altarpiece he did not just look until ‘it happened that he came upon someone in the town who pleased him,’ making ‘no effort to exercise his brain further.’ While we might think that swarthy people look brooding more easily than blonds, we are unlikely to link an artist’s complexion to his style. But if portions of Bellori’s text are alien to us, its structure is understandable. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

The Virtuoso of Compassion Ingrid D

The Virtuoso of Compassion Ingrid D. Rowland MAY 11, 2017 ISSUE The Guardian of Mercy: How an Extraordinary Painting by Caravaggio Changed an Ordinary Life Today by Terence Ward Arcade, 183 pp., $24.99 Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, October 7, 2016–January 22, 2017; and the Musée du Louvre, Paris, February 20–May 22, 2017 Catalog of the exhibition by Annick Lemoine and Keith Christiansen Metropolitan Museum of Art, 276 pp., $65.00 (distributed by Yale University Press) Beyond Caravaggio an exhibition at the National Gallery, London, October 12, 2016–January 15, 2017; the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, February 11–May 14, 2017 Catalog of the exhibition by Letizia Treves and others London: National Gallery, 208 pp., $40.00 (distributed by Yale University Press) The Seven Acts of Mercy a play by Anders Lustgarten, produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon- Avon, November 24, 2016–February 10, 2017 Caravaggio: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 1607 Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples Two museums, London’s National Gallery and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, mounted exhibitions in the fall of 2016 with the title “Beyond Caravaggio,” proof that the foul-tempered, short-lived Milanese painter (1571–1610) still has us in his thrall. The New York show, “Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio,” concentrated its attention on the French immigrant to Rome who became one of Caravaggio’s most important artistic successors. The National Gallery, for its part, ventured “beyond Caravaggio” with a choice display of Baroque paintings from the National Galleries of London, Dublin, and Edinburgh as well as other collections, many of them taken to be works by Caravaggio when they were first imported from Italy. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

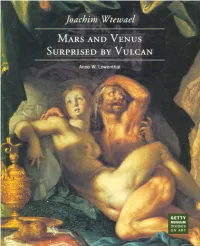

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

The Arts Thrive Here

Illustrated THE ARTS THRIVE HERE Art Talks Vivian Gordon, Art Historian and Lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: REMEMBERING BIBLICAL WOMEN ARTISTS IN THEIR STUDIOS Monday, April 13, at 1PM Wednesday, May 20, at 1PM Feast your eyes on some of the most Depicting artists at work gives insight into the beautiful paintings ever. This illustrated talk will making of their art as well as their changing status examine how and why biblical women such as in society.This visual talk will show examples Esther, Judith, and Bathsheba, among others, from the Renaissance, the Impressionists, and were portrayed by the “Masters.” The artists Post-Impressionists-all adding to our knowledge to be discussed include Mantegna, Cranach, of the nature of their creativity and inspiration. Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt. FINE IMPRESSIONS: CAILLEBOTTE, SISLEY, BAZILLE Monday, June 15, at 1PM This illustrated lecture will focus on the work of three important (but not widely known) Impressionist painters. Join us as Ms. Gordon introduces the art, lives and careers of these important fi gures in French Impressionist art. Ines Powell, Art Historian and Educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: ALBRECHT DURER and HANS HOLBEIN the ELDER Thursday, April 23, at 1PM Unequaled in his artistic and technical execution of woodcuts and engravings, 16th century German artist Durer revolutionized the art world, exploring such themes as love, temptation and power. Hans Holbein the Elder was a German painter, a printmaker and a contemporary of Durer. His works are characterized by deep, rich coloring and by balanced compositions. -

Of Painting and Seventeenth-Century

Concerning the 'Mechanical' Parts of Painting and the Artistic Culture of Seventeenth-CenturyFrance Donald Posner "La representation qui se fait d'un corps en trassant making pictures is "mechanical" in nature. He understood simplement des lignes, ou en meslant des couleurs, est proportion, color, and perspective to be mere instruments in consider6e comme un travail m6canique." the service of the painter's noble science, and pictorial --Andre F61ibien, Confirences de l'Acadimie Royale de Pezn- elements such as the character of draftsmanship or of the ture et de Sculpture, Paris, 1668, preface (n.p.). application of paint to canvas did not in his view even warrant notice-as if they were of no more consequence in les Connoisseurs, ... avoir veus "... apr6s [les Tableaux] judging the final product than the handwriting of an author d'une distance s'en en raisonnable, veiiillent approcher setting out the arguments of a philosophical treatise.3 Paint- suite pour en voir l'artifice." ers who devoted their best efforts to the "mechanics of the de Conversations sur connoissance de la -Roger Piles, la art" were, he declared, nothing more than craftsmen, and 300. peinture, Paris, 1677, people who admired them were ignorant.4 Judging from Chambray's text, there were a good many A of Champion French Classicism and His Discontents ignorant people in France, people who, in his view seduced ca. 1660 by false fashion, actually valued the display of mere craftsman- In Roland Freart de his 1662 Chambray published IdMede la ship. Chambray expresses special -

No, Not Caravaggio

2 SEPTEMBER2018 I valletta 201 a NO~ NOT CARAVAGGIO Crowds may flock to view Caravaggio's Beheading of StJohn another artist, equally talented, has an even a greater link with-Valletta -Mattia Preti. n 1613, in the small town of Taverna, in Calabria, southern Italy, a baby boy was born who would grow up to I become one of the world's greatest and most prolific artists of his time and to leave precious legacies in Valletta and the rest of Malta. He is thought to have first been apprenticed to Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, who was known as a follower and admirer of Caravaggio. His brother, Gregorio, was also a painter and painted an altarpiece for the Chapel of . the world designed and built by Preti, sometime in the 1620s Preti joined.him in the Langue of Aragon, Preti offered to do and no fewer than seven of his paintings Rome. · more wor1< on the then new and very, hang within it. They include the There he grasped Caravaggio's bareSt John's Co-Cathedral. Grand monumental titular painting and others techniques and those of other famous Master Raphael Cotoner accepted his which fit perfectly in the architecturally and popular artists of the age, including offer·and commissioned him to decorate designed stone alcoves he created for Rubens and Giovanni Lanfranco. the whole vaulted ceiling. The them. Preti spent time in Venice between 1644 magnificent scenes from the life of St In keeping with the original need for and 1646 taking the chance to observe the John took six years and completely the church, the saints in the images are all opulent Venetian styles and palettes of transformed the cathedral. -

The Baroque Underworld Vice and Destitution in Rome

press release The Baroque Underworld Vice and Destitution in Rome Bartolomeo Manfredi, Tavern Scene with a Lute Player, 1610-1620, private collection The French Academy in Rome – Villa Medici Grandes Galeries, 7 October 2014 – 18 January 2015 6 October 2014 11:30 a.m. press premiere 6:30 p.m. – 8:30 p.m. inauguration Curators : Annick Lemoine and Francesca Cappelletti The French Academy in Rome - Villa Medici will present the exhibition The Baroque Underworld. Vice and Destitution in Rome, in the Grandes Galeries from 7 October 2014 to 18 January 2015 . Curators are Francesca Cappelletti, professor of history of modern art at the University of Ferrara and Annick Lemoine, officer in charge of the Art history Department at the French Academy in Rome, lecturer at the University of Rennes 2. The exhibition has been conceived and organized within the framework of a collaboration between the French Academy in Rome – Villa Medici and the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, where it will be shown from 24 February to 24 May 2015. The Baroque Underworld reveals the insolent dark side of Baroque Rome, its slums, taverns, places of perdition. An "upside down Rome", tormented by vice, destitution, all sorts of excesses that underlie an amazing artistic production, all of which left their mark of paradoxes and inventions destined to subvert the established order. This is the first exhibition to present this neglected aspect of artistic creation at the time of Caravaggio and Claude Lorrain’s Roman period, unveiling the clandestine face of the Papacy’s capital, which was both sumptuous and virtuosic, as well as the dark side of the artists who lived there. -

Episode 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights

EpisodE 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights Caravaggio’s painting contains a lesson to the viewer about the transience of youth, the perils of sensual pleasure, and the precariousness of life. Questions to Consider 1. How do you react to the painting? Does your impression change after the first glance? 2. What elements of the painting give it a sense of intimacy? 3. Do you share Januszczak’s sympathies with the lizard, rather than the boy? Why or why not? Other works Featured Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607-1610), Caravaggio Young Bacchus (1593), Caravaggio The Fortune Teller (ca. 1595), Caravaggio The Cardsharps (ca. 1594), Caravaggio The Taking of Christ (1602), Caravaggio The Lute Player (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Contarelli Chapel paintings, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi: The Calling of St. Matthew, The Martyrdom of St. Matthew, The Inspiration of St. Matthew (1597-1602), Caravaggio The Beheading of St. John the Baptist (1608), Caravaggio The Sacrifice of Isaac (1601-02), Caravaggio David (1609-10), Caravaggio Bacchus (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Boy with a Fruit Basket (1593), Caravaggio St. Jerome (1605-1606), Caravaggio ca. 1595-1600 (oil on canvas) National Gallery, London A Table Laden with Flowers and Fruit (ca. 1600-10), Master of the Hartford Still-Life 9 EPTAS_booklet_2_20b.indd 10-11 2/20/09 5:58:46 PM EpisodE 6 Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci Highlights A robbery and attempted forgery in 1911 helped propel Mona Lisa to its position as the most famous painting in the world. Questions to Consider 1.