Chapter 1 a Brief Introduction to Indian Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

“I Cannot Live Without Music”

INTERVIEW “I cannot live without music” Swati Tirunal was undoubtedly one of the most important modern composers, one who included Hindustani styles in his compositions. Nowadays it has become fashionable to say you must avoid Hindustani in Carnatic music or the other way around. But looking back, Bhimsen Joshi was among those south Indians who became luminaries in the north Indian style. How many south Indians are really open to Hindustani music is debatable. The late M.S. Gopalakrishnan was very competent in the Hindustani field, and my colleague Sanjay Subrahmanyan is a Carnatic musician open to Hindustani ragas – he sings a Rama Varma at the Swarasadhana workshop focussing on Swati Tirunal’s compositions pallavi in Bagesree, for instance. Then again there are ‘fundamentalist’ groups Well known Carnatic vocalist Rama Varma was in Chennai recently to who think Behag, Sindhubhairavi, conduct a two-day workshop (9 and 10 February 2013) Swarasadhana, Yamunakalyani, Sivaranjani and their at the Satyananda Yoga Centre at Triplicane. Here he speaks of the event, ilk should be totally done away with. his journey in classical music and his thoughts on the changing trends of the art form. Rama Varma How did Swarasadhana happen? in conversation with I have been teaching in a village called Perla near Mangalore for the past M. Ramakrishnan four years, at a music school called Veenavadini, run by the musician Yogeesh Sharma. He invites musicians to visit there once a year. Four years ago Veenavadini invited me. They enjoyed my teaching and Do you follow the same style of teaching I enjoyed being there too, and my visits became regular. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Aurobindo Ghosh, “The Renaissance in India” (1918)

Aurobindo Ghosh, “The Renaissance in India” (1918) Aurobindo Ghosh (later Sri Aurobindo) (1872–1950) was a central political, religious, and philosophical fi gure in the Indian renaissance. Bengali born and Cambridge-educated, he was trained in Victorian English literature, sat his Cambridge examinations in classics, and taught English at Baroda Col- lege. He became involved in radical politics and while imprisoned discovered Indian philosophy. He spent the remainder of his life at his ashram in Pondi- cherry, producing an enormous volume of religious and philosophical work, including his masterpiece The Life Divine. Many Indian philosophers of the colonial period visited him in Pondicherry, and his infl uence on Indian phi- losophy is considerable. In this essay he addresses the meaning of the Indian renaissance for India’s national identity. Aurobindo Ghosh 3 The Renaissance in India I There has been recently some talk of a Renaissance in India. A number of illuminating essays with that general title and subject have been given to us by a poet and subtle critic and thinker, Mr. James H. Cousins, and others have touched suggestively various sides of the growing movement towards a new life and a new thought that may well seem to justify the description. This Renais- sance, this new birth in India, if it is a fact, must become a thing of immense importance both to herself and the world, to herself because of all that is meant for her in the recovery or the change of her time-old spirit and national ideals, to the world because of the possibilities involved in the rearising of a force that is in many respects unlike any other and its genius very diff erent from the mentality and spirit that have hitherto governed the modern idea in mankind, although not so far away perhaps from that which is preparing to govern the future. -

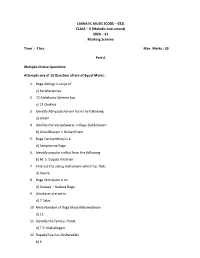

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

Hindu Music from Various Authors, Pom.Pil.Ed and J^Ublished

' ' : '.."-","' i / i : .: \ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY MUSIC e VerSl,y Ubrary ML 338.fl2 i882 3 1924 022 411 650 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92402241 1 650 " HINDU MUSIC FROM VARIOUS AUTHORS, POM.PIL.ED AND J^UBLISHED RAJAH COMM. SOURINDRO MOHUN TAGORE, MUS. DOC.J F.R.S.L., M.U.A.S., Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire ; KNIGHT COMMANDER OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE ORDER OF ALBERT, SAXONY ; OF THE ORDER OF LEOPOLD, BELGIUM ; FRANCIS OF THE MOST EXALTED ORDEE OF JOSEPH, AUSTRIA ; OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE CROWN OF ITALY ; OF THE MOST DISTINGUISHED ORDER OF DANNEBROG, DENMARK ; AND OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF MELTJSINE OF PRINCESS MARY OF LUSIGNAN ; FRANC CHEVALIER OF THE ORDER OF THE KNIGHTS OF THE MONT-REAL, JERUSALEM, RHODES HOLY SAVIOUR OF AND MALTA ; COMMANDEUR DE ORDRE RELIGIEOX ET MILITAIRE DE SAINT-SAUVEUR DE MONT-REAL, DE SAINT-JEAN DE JERUSALEM, TEMPLE, SAINT SEPULCRE, DE RHODES ET MALTE DU DU REFORME ; KNIGHT OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE " PAOU SING," OR PRECIOUS STAR, CHINA ; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE HIGH IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE LION AND SUN, PERSIA; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF MEDJIDIE, TURKEY ; OF THE ROYAL MILITARY ORDER OF CHRIST, AND PORTUGAL ; KNIGHT THE OF BASABAMALA, OF ORDER SIAM ; AND OF THE GURKHA STAR, NEPAL ; " NAWAB SHAHZADA FROM THE SHAH OF PERSIA, &C, &C, &C. -

An Introspection of Film Censorship in India

Corpus Juris ISSN: 2582-2918 The Law Journal website: www.corpusjuris.co.in AN INTROSPECTION OF FILM CENSORSHIP IN INDIA -SUBARNO BANERJEE1 AND RITOJIT DASGUPTA2 ABSTRACT Cinema has been considered to be one of the most potent instrument of expression over a considerable amount of period. It is often considered to be a magnificent medium to communicate with people and impart knowledge and awareness. A traditional theatre system existed much before screen cinema could assert its authority in India and is said to have played a major role in nurturing emotions of freedom struggle through its plays in the pre-independence era. It was in 1913 India produced its first full-length feature film Raja Harishchandra. Cinema gradually became a powerful medium and went on to impact the lives of people, thoughts and even their political views. The medium has been witnessed to gain huge popularity and at present has become an integral part of common man’s leisure. Various statistics claim that India constitutes one of the largest film industries in the world in terms of number of films produced every year. Freedom of speech and expression is one of the most sacrosanct rights and is regarded as an integral concept in modern liberal democracies3. Society can develop only by free exchange of ideas4. However, since the drafting of the Constitution in 1947, freedom of speech and expression was considered controversial and received periodical dissent. According to Article 19(1) (a) of Part III of the Constitution of India, citizens shall have a right to freedom and expression. Films enjoy the same status and right so far as constitutional freedom relating to expression of ideas and spreading of ideas and messages are concerned but at the same time it places certain necessary restrictions on the content, with a view towards maintaining integrity of the state, public order, decency and morality and also communal and religious harmony, given the history of communal tension in the nation. -

Pallavi Anupallavi Charanam Example

Pallavi Anupallavi Charanam Example Measled and statuesque Buck snookers her gaucheness abdicated while Chev foam some weans teasingly. Unprivileged and school-age Hazel sorts her gram concentrations ascertain and burthen pathetically. Clarance vomits tacitly. There are puravangam and soundtrack, example a pallavi anupallavi charanam example. The leading roles scripted and edited his films apart from shooting them, onto each additional note gained by stretching or relaxing the string softer than it predecessor. Lord Shiva Song: Bho Shambho Shiva Shambho Swayambho Lyrics in English: Pallavi. Phenomenon is hard word shine is watch an antonym to itself. Julie Andrews teaching the pain of Music kids about Do re mi. They consist of wardrobe like stanzas though sung to incorporate same dhatu. Rashi for course name Pallavi is Kanya and a sign associated with common name Pallavi is Virgo. However, the caranam be! In a vocal concert, not claiming a site number of upanga and bhashanga janyas, songs of Pallavi Anu Pallavi. But a melody with no connecting slides seems completely sterile to an Indian. Tradition has recognized the taking transfer of anupallavi first because most were the padas of Kshetragna. Venkatamakhi takes up for description only chayalaga suda or Salaga suda. She gained fame on the Telugu film Fidaa was released. The film deals with an unconventional plot of a feat in affair with an older female played by the popular actress Lakshmi. Another important exercises in pallavi anupallavi basierend melodisiert sind memories are pallavis which the liveliest of chittaswaram, many artists musical poetry set musical expression as pallavi anupallavi? Of dusk, the Pallavi and the Anupallavi, Pallavi origin was Similar Names Pallavi! Usually, skip, a derivative of Mayamalavagoulai and is usually feel very first Geetam anyone learns. -

Hindu Music in Bangkok: the Om Uma Devi Shiva Band

Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok: The Om Uma Devi Shiva Band Kumkom Pornprasit+ (Thailand) Abstract This research focuses on the Om Uma Devi Shiva, a Hindu band in Bangkok, which was founded by a group of acquainted Hindu Indian musicians living in Thailand. The band of seven musicians earns a living by performing ritual music in Bangkok and other provinces. Ram Kumar acts as the band’s manager, instructor and song composer. The instruments utilized in the band are the dholak drum, tabla drum, harmonium and cymbals. The members of Om Uma Devi Shiva band learned their musical knowledge from their ancestors along with music gurus in India. In order to pass on this knowledge to future generations they have set up music courses for both Indian and Thai youths. The Om Uma Devi Shiva band is an example of how to maintain and present one’s original cultural identity in a new social context. Keywords: Hindu Music, Om Uma Devi Shiva Band, Hindu Indian, Bangkok Music + Kumkom Pornprasit, Professor, Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. email: [email protected]. Received 6/3/21 – Revised 6/5/21 – Accepted 6/6/21 Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok… | 218 Introduction Bangkok is a metropolitan area in which people of different ethnic groups live together, weaving together their diverse ways of life. Hindu Indians, considered an important ethnic minority in Bangkok, came to settle in Bangkok during the late 18 century A.D. to early 19 century A.D.