Immanuel Kant's Account of Cognitive Experience And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUMANISM Religious Practices

HUMANISM Religious Practices . Required Daily Observances . Required Weekly Observances . Required Occasional Observances/Holy Days Religious Items . Personal Religious Items . Congregate Religious Items . Searches Requirements for Membership . Requirements (Includes Rites of Conversion) . Total Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals . Death . Autopsies . Mourning Practices Sacred Writings Organizational Structure . Headquarters Location . Contact Office/Person History Theology 1 Religious Practices Required Daily Observance No required daily observances. Required Weekly Observance No required weekly observances, but many Humanists find fulfillment in congregating with other Humanists on a weekly basis (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) or other regular basis for social and intellectual engagement, discussions, book talks, lectures, and similar activities. Required Occasional Observances No required occasional observances, but some Humanists (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) celebrate life-cycle events with baby naming, coming of age, and marriage ceremonies as well as memorial services. Even though there are no required observances, there are several days throughout the calendar year that many Humanists consider holidays. They include (but are not limited to) the following: February 12. Darwin Day: This marks the birthday of Charles Darwin, whose research and findings in the field of biology, particularly his theory of evolution by natural selection, represent a breakthrough in human knowledge that Humanists celebrate. First Thursday in May. National Day of Reason: This day acknowledges the importance of reason, as opposed to blind faith, as the best method for determining valid conclusions. June 21 - Summer Solstice. This day is also known as World Humanist Day and is a celebration of the longest day of the year. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy The Renaissance was one of the most innovative periods in Western civi- lization.1 New waves of expression in fijine arts and literature bloomed in Italy and gradually spread all over Europe. A new approach with a strong philological emphasis, called “humanism” by historians, was also intro- duced to scholarship. The intellectual fecundity of the Renaissance was ensured by the intense activity of the humanists who were engaged in collecting, editing, translating and publishing the ancient literary heri- tage, mostly in Greek and Latin, which had hitherto been scarcely read or entirely unknown to the medieval world. The humanists were active not only in deciphering and interpreting these “newly recovered” texts but also in producing original writings inspired by the ideas and themes they found in the ancient sources. Through these activities, Renaissance humanist culture brought about a remarkable moment in Western intel- lectual history. The effforts and legacy of those humanists, however, have not always been appreciated in their own right by historians of philoso- phy and science.2 In particular, the impact of humanism on the evolution of natural philosophy still awaits thorough research by specialists. 1 By “Renaissance,” I refer to the period expanding roughly from the fijifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century, when the humanist movement begun in Italy was difffused in the transalpine countries. 2 Textbooks on the history of science have often minimized the role of Renaissance humanism. See Pamela H. Smith, “Science on the Move: Recent Trends in the History of Early Modern Science,” Renaissance Quarterly 62 (2009), 345–75, esp. -

An Interpretation of Kant's Political Philosophy in Light of His Critical-Regulative Method

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 11-2011 Politics, history, critique: An interpretation of Kant's political philosophy in light of his critical-regulative method. Dilek Huseyinzadegan DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Huseyinzadegan, Dilek, "Politics, history, critique: An interpretation of Kant's political philosophy in light of his critical-regulative method." (2011). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 110. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/110 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POLITICS, HISTORY, CRITIQUE: AN INTERPRETATION OF KANT’S POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY IN LIGHT OF HIS CRITICAL-REGULATIVE METHOD A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2011 By Dilek Huseyinzadegan Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. The Department of Philosophy at DePaul University provided a doctoral scholarship for eight years of graduate study. I thank the faculty for their help and support throughout this process, especially my dissertation director Avery Goldman, whose approach to Kant and his method inspired this project in the first place, my committee members Elizabeth Millàn, Kevin Thompson, and Rick Lee, whose graduate seminars gave rise to numerous fruitful discussions on German Idealism and Romanticism, history and politics, and critical theory. -

A Short Course on Humanism

A Short Course On Humanism © The British Humanist Association (BHA) CONTENTS About this course .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction – What is Humanism? ............................................................................. 7 The course: 1. A good life without religion .................................................................................... 11 2. Making sense of the world ................................................................................... 15 3. Where do moral values come from? ........................................................................ 19 4. Applying humanist ethics ....................................................................................... 25 5. Humanism: its history and humanist organisations today ....................................... 35 6. Are you a humanist? ............................................................................................... 43 Further reading ........................................................................................................... 49 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 1 03/05/2013 13:08 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 2 03/05/2013 13:08 About this course This short course is intended as an introduction for adults who would like to find out more about Humanism, but especially for those who already consider themselves, or think they might be, humanists. Each section contains a concise account of humanist The unexamined life thinking and a section of questions -

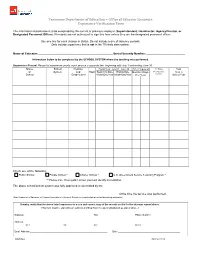

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Was Immanuel Kant a Humanist? This Article Continues FI 'S Ongoing Series on the Precursors of Modern-Day Humanism

Was Immanuel Kant a Humanist? This article continues FI 's ongoing series on the precursors of modern-day humanism. Finngeir Hiorth erman philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is can be found in antiquity, the proofs were mainly developed generally regarded to be one of the greatest philos- in the Middle Ages. And during this time Thomas Aquinas Gophers of the Western world. His reputation is based was their major advocate and systematizer. mainly on his contributions to the theory of knowledge and Kant undertook a new classification of the proofs, or to moral philosophy, although he also has contributed to other arguments, as we shall call them. He distinguished between parts of philosophy, including the philosophy of religion. Kant ontological, cosmological, and physico-theological arguments, was a very original philosopher, and his historical importance and rejected them. He believed that there were no other is beyond any doubt. And although some contemporary arguments of importance. Thus, for Kant, it was impossible humanists do not share the general admiration for Kant, he to prove the existence of God. to some extent, remains important for modern humanism. God's position was not improved in Kant's next important Kant is sometimes regarded to be the philosopher of the publication, Foundation of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785). Protestants, just as Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) is considered In this rather slim (about seventy pages) publication, Kant to be the philosopher of the Catholics. One might think a gave an analysis of the foundation of ethics. What is philosopher who is important to Protestantism is an unlikely remarkable from a humanistic point of view is that God is candidate for a similar position among secular humanists. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Connecting Science and Wisdom Derstood Them in Her Lifetime

ew concepts are so rich in meaning and at the same time so open to a diversity of interpretations as is “nature.” “Na- ture” refers to the immense reality in which every thing and Fperson exists and of which they constitute an integral part. It is precisely this reality of nature that I will discuss, tracing briefly The “Book of Nature” some of its characteristics as Chiara Lubich experienced and un- Connecting Science and Wisdom derstood them in her lifetime. The term “nature” generally refers to all existing things, with Sergio Rondinara particular regard to their objective configuration and their essen- Sophia University Institute tial constitutive principles. This connection between totality and essentiality—as the etymology of the word “nature” suggests1—is also found in Chiara’s reflections. Their deeply theological charac- Rondinara explores the reality of nature, both in its totality and in ter must be understood not so much as human speech about God its essence, from different perspectives. In so doing, he discusses how and the divine mystery but in their proper meaning as a subjective Chiara Lubich envisions nature in relation to God and humankind. genitive—a word that is both noun and verb.2 In language that First, he examines the God- nature relation as Chiara understood it, as seems ordinary, her texts shine with clarity and incisiveness. They both immanent and transcendent. Then, he turns to Chiara’s notion of offer God’s vision of things and of the natural world, a contempla- nature as an ongoing “event” in history leading to the recapitulation of tive gaze that—metaphorically speaking—comes from the “eyes of all things in God. -

Kant on Formative Power

26 Ina Goy INA GOY KANT(Concordia ON FORMATIVE University, Montreal POWER) The notion of a formative1 power is one of the most obscure in Kant’s theory of biology . Before I discuss Kant’s biological use of the term ‘formative power’, in section 1 of this paper I provide a list of all passages in which Kant uses the term, claiming that the older meaning of ‘formative power’ in Kant’s writings is an epi- stemological one, whereas the biological meaning of the term ap- pears not before the mid-1780s. I present and discuss some of thoseCriti passagesque of thein closer power detail, of jud andgment give a precise interpretation of the most central passage in Kant’s philosophy2 of biology in §65 of the . I defend the view that, for Kant, the formative power is a basic, immaterial, and intrinsic natural power in the organism belonging to an account of final causation. As a cause, it does not generate form and matter, or the matter of organisms, but only the end-directed teleological3 form of the matter of an organism. AsKant an on alternative vital force. Metaphysical to White’s concernsclaim ver- sus1 scientific practice Kants Philosophie der Natur. Ihre Entwick- lungFor imrecent inquiries seeund H. van ihre den WirkungBerg, Bildungskraft, in E.-O. und Onnasch Bildungstrieb (ed.), bei ibid. Der Baum imOpus Baum. postumumModellkörper, reproductive, Berlin Systeme- New und York, die DeDifferenzGruyterzwischen, 2009, pp. Leben 115- digem136; G.F. und Frigo, Unlebendigem bei Kant und Bonnet ibidKant, in , pp. 9-23; T. BlCheung,umenbach and Kant on mechanism and teleology in nature: the case of the formative drive The problem of animal generation in early, in modern, pp. -

CHAPTER 2.1 Augustine: Commentary

CHAPTER 2.1 Augustine: Commentary Augustine Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis (henceforth Augustine) was born in 354 A.D. in the municipium of Thagaste (modern day Souk Ahras, Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia). He died in 430, as the Arian1 Vandals besieged the city of Hippo where he was bishop, marking another stage in the demise of the Roman Empire. Rome had already been sacked in 410 by Alaric the Visigoth, but the slow decline of Roman grandeur took place over a period of about 320 years which culminated in 476 when Romulus Augustus, the last Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, was deposed by Odoacer, a Germanic chieftain. Augustine thus lived at a time which heralded the death knell of the ancient world and the beginnings of mediaeval western European Christendom.2 Augustine‘s great legacy to western civilization is that intellectually he united both worlds in drawing from the ancient thought of Greece and Rome and providing a Christian understanding of the intellectual achievements of the ancients. His new synthesis is a remarkable achievement even today and for those of us, who remain Christians in the West, our debates, agreements and disagreements are still pursued in Augustine‘s shadow.3 1 Arianism was a schismatic sect of Christianity that held the view that the Second Person of the Trinity, Christ, is created and thus does not exist eternally with the Father. 2 See J. M. Rist‘s magnificent Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003. Rist notes that, ‗Despite his lack of resources he managed to sit in judgment on ancient philosophy and ancient culture.‘ p.