Flags and Emblems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. George's Cross and St. John's Cross

FAHNEN FLAGS DRAPEAUX (Proceedings of the 15'^ ICV, Zurich, 1993) ST GEORGE'S CROSS AND ST JOHN'S CROSS care for pilgrims First came the Order of the Hospitallers named after St John the Baptist, Christ's cousin. The Paul Dechaix founders are said to be Italian merchants from Amalfi, south of Naples, one of the four great maritime cities Introduction along with Venice, Genoa and Pisa. The armorial bea A vexillologist even before the word wds coined, I am rings of Amalfi consist of a blue field bearing a white only an amateur if a dedicated one. Coming from Savoy, eight-pointed cross known nowadays as Maltese Cross and welcomed by my friendly neighbours in Aldo Ziggiotto has written an article about the Amalfi Switzerland, I think proper to honour our two countries republic said to date from 838. Ziggioto thinks he can by means of flags. As a matter of fact, I will have the state that the original Hospitallers were really Amalfi opportunity to state that their emblemiS proceed from merchants, their Order dating from 1048. On the otner the same source and are identical in many respects. hand, a blue national banner bearing a typical white They belong to the group of flags with a white cross eight-pointed cross was in existence. The Italian repu upon red ground which I purpose to examine In the blic has created, for the Navy, a flag bearing a blazon same way, I will try to list the flags with inverted colours, composed of four others, those of Venice, Genoa, that is a red cross on white ground, called St George's Amalfi and Pisa, the whole being encompassed with Cross. -

Flags: Stripes and Crosses

Flags: stripes and crosses There are things that we take for granted in use, with few exceptions, two different our life, not bothering what their origins or approaches with their flags. real meanings are. Such are the flags of our One is the striped, tricolour- kind of flag. nations. We salute them, we respect them The tricolour origins from the French but nobody, at least very few of us wonder revolution, where the three colours ever, that maybe a hundred years ago, our symbolised brotherhood, freedom, and grandfathers, or the fathers of our equality. grandfathers, (or the fathers of our Tricolours became popular in the time of grandfathers' fathers or their fathers; if we the birth of the nations in the 19th century. want to quote some Monty Python here) Some countries, however, rotated the may have respected other flags. This is vertical position to horizontal position. especially true for Germany or the Eastern European "newly formed" states. It was not necessary, nevertheless, that the Has the highly regarded reader audience country is a republic to have a tricolour- ever wondered about the origins of their type of flag. Just think of the black-white- national flags? Have you ever realised that red flag of the Bismarck- Germany. Or different cultural circles use similar today's Netherlands. symbols for their flags and these differ Among the countries being dealt with on from area to area. this website, the followings have striped Northern European and European countries flags: The other approach, used in Northern had on each other. Except for Finland, all Europe is the crossed flag. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

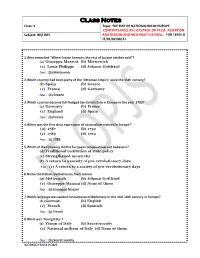

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

Flags of Asia

Flags of Asia Item Type Book Authors McGiverin, Rolland Publisher Indiana State University Download date 27/09/2021 04:44:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/12198 FLAGS OF ASIA A Bibliography MAY 2, 2017 ROLLAND MCGIVERIN Indiana State University 1 Territory ............................................................... 10 Contents Ethnic ................................................................... 11 Afghanistan ............................................................ 1 Brunei .................................................................. 11 Country .................................................................. 1 Country ................................................................ 11 Ethnic ..................................................................... 2 Cambodia ............................................................. 12 Political .................................................................. 3 Country ................................................................ 12 Armenia .................................................................. 3 Ethnic ................................................................... 13 Country .................................................................. 3 Government ......................................................... 13 Ethnic ..................................................................... 5 China .................................................................... 13 Region .................................................................. -

Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a Case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian Group in Toronto

Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a Case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian Group in Toronto By Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Trinity College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar 2016 Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian group in Toronto PhD 2016 Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar University of St.Michael’s College Abstract This study explores how the Macedono-Bulgarian and Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox churches in Toronto have attuned themselves to the immigrant community—specifically to post-1990 immigrants who, while unchurched and predominantly secular, have revived diaspora churches. This paradox raises questions about the ways that religious institutions operate in diaspora, distinct from their operations in the country of origin. This study proposes and develops the concept “institutional vernacularization” as an analytical category that facilitates assessment of how a religious institution relates to communal factors. I propose this as an alternative to secularization, which inadequately captures the diaspora dynamics. While continuing to adhere to their creeds and confessional symbols, diaspora churches shifted focus to communal agency and produced new collective and “popular” values. The community is not only a passive recipient of the spiritual gifts but is also a partner, who suggests new forms of interaction. In this sense, the diaspora church is engaged in vernacular discourse. The notion of institutional vernacularization is tested against the empirical results of field work in four Greater Toronto Area churches. -

A Democratic Design? the Political Style of the Northern Ireland Assembly

A Democratic Design? The political style of the Northern Ireland Assembly Rick Wilford Robin Wilson May 2001 FOREWORD....................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................4 Background.........................................................................................................................................7 Representing the People.....................................................................................................................9 Table 1 Parties Elected to the Assembly ........................................................................................10 Public communication......................................................................................................................15 Table 2 Written and Oral Questions 7 February 2000-12 March 2001*........................................17 Assembly committees .......................................................................................................................20 Table 3 Statutory Committee Meetings..........................................................................................21 Table 4 Standing Committee Meetings ..........................................................................................22 Access to information.......................................................................................................................26 Table 5 Assembly Staffing -

CHAPTER IV at the Census Taken in 1911, the Last Before the Outbreak Of

CHAPTER IV THE ENEMY WITHIN THE GATES AT the census taken in 1911, the last before the outbreak of the war, there were within the Commonwealth 32,990 persons who were born in Germany, and 2,774 born in Austria- Hungary. These figures do not afford a clue to the total number of inhabitants of German origin, or who had ties of affinity connecting them with enemy countries, nor do the census statistics afford a dependable means of estimating the probable number of such persons. As will be explained in a later section of this chapter, there were in South Australia and Queensland, and to a lesser extent in Victoria and Tasmania, towns whose population consisted mainly of people of Australian birth, and whose forbears had for several generations been Australian, but who nevertheless were senti- nientally attached to Germany as the land of their family origin. Very many of these habitually spoke German, were Lutheran in religion, and piobably had never seriously thought of being placed in the predicament of having to discriminate between the allegiance which they owed to the, British Crown and nation by virtue of citizenship, and the feeling--which there had never been any need for them to suppress-of affection for the L'nterland of their ancestors, whence came to them their literature, language and religion. It was not uii- natural that some of the many thousands of German descent were prepared, from recklessness, or bravado, or quite honest patriotic motives, to help the German cause if they could, and their intimate knowledge of Australia and of Australian industry increased their power of injuring her cause. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Vexillum, March 2018, No. 1

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association March 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Mars 2018 1 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 2017 NAVA Membership Map 3 Steamboat’s a-Comin’: Flags Used Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Afloat in the Nineteenth Century 4 The Mississippi Identity: Summary of an Academic Project in Flag Design 11 Flag Heritage Foundation: Japanese Heraldry and Heraldic Flags 12 Regional Groups Report: PFA and VAST 12 • Grants Committee Report • Letters • New Flags • Projected Publication Schedule 13 11 Oh Say, Can You See...? 14 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 16 Treasurer’s Report 16 Flags for the Fallen 18 Annual Meeting Notice, Call for Papers 24 18 4 2 | March 2018 • Vexillum No. 1 March / Mars 2018 Issue 1 / Numéro 1 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: No. 1 Welcome to the first edition of Vexillum. Please allow me to explain its origins and our Research and news of the North American plans for it. Vexillological Association / Recherche et NAVA has a long history of publishing for its members and others interested in vexill- nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine ological matters. NAVA News began in 1967 as a newsletter about association affairs, and de vexillologie. Published quarterly / Publié later expanded its coverage to include reprints of newspaper articles about flags and original quatre fois par an. research papers. Raven has delivered twenty-four volumes of peer-reviewed vexillological Please submit correspondence and research since 1994. In 2013, Flag Research Quarterly was launched to provide a forum for submissions to / Veuillez envoyer toute correspondance à l’adresse suivante: amply illustrated, shorter research articles. -

Symbols of Ireland

Activity Book for Families Symbols of Ireland A symbol is something that represents another thing – for example, a shamrock stands for Ireland. If you see a shamrock in the exhibition, it will mean that the people who use the symbol want to show their attachment to Ireland. Such symbols help people to feel that they belong to a group or to a country. My Name: • Search the Soldiers and Chiefs galleries to discover how armies have used Irish symbols since the 17th century. • Examine the evidence in the objects and pictures on display for examples of symbols used for different reasons. • You will find symbols on uniforms and flags, but also in History Detective Be a some unexpected places. 1 Soldiers and Chiefs Galleries To find the symbols in the exhibits just follow the numbers shown on these plans of all the galleries. The numbers on the plans match the activity numbers. The title with each plan is the name of that gallery. Note to Adults: Answers to the activities are on the back page. First floor The British Garrison Irish Soldiers in Introduction in Ireland Warfare in Ireland Foreign Armies 1 3 2 Balcony Irish in the American Irish in the British The Wild Geese Civil War Service Taking Flight 8 4 5 6 5 5 9 5 7 Claiming the Future The Emergency: The Second World War The Irish Wars The First World War Ground floor Defending the Peace 12 12 12 14 14 14 11 10 1916 – The Easter Rising 13 You can find explanations of military terms in the booklet, 'Military Speak', a glossary to accompany these Activity Books, which is available at the start of the exhibition or at Museum reception. -

The Vietnam War, 1965-1975

How I will compress four lectures into one because I’ve run out of time. A last‐minute addition to my bibliography: • B.G. Burkett (Vanderbilt, 66) and Glenna Whitley, Stolen Valor: How the Vietnam Generation was robbed of its Heroes and its History (Dallas, 1998). • Burkett makes many claims in this book, but the most fascinating aspect of it is his exposure of the “phony Vietnam veteran,” a phenomenon that still amazes me. “Many Flags” campaign ‐ Allied support 1.) South Korea –largest contingent – 48,000(would lose 4407 men)‐US financial support 2.) Australia – 8000, lost 469 3.)New Zealand, 1000, lost 37 4.) Thailand – 12,000 troops, 351 lost 5.) Philippines – medical and small number of forces in pacification 6.) Nationalist China –covert operations American Force levels/casualties in Vietnam(K=killed W=wounded) 1964 23,200 K 147 W 522 1965 190,000 K 1369 W 3308 1966 390,000 5008 16,526 1967 500,000 9377 32,370 1968 535,000 14,589 46,797 1969 475,000 9414 32,940 1970 334,000 4221 15,211 1971 140,000 1381 4767 1972 50,000 300 587 Soviet and Chinese Support for North Vietnam • 1.) Despite Sino‐Soviet dispute and outbreak of Cultural Revolution in China, support continues • 2.) Soviet supply of anti‐aircraft technology and supplies to the North –along with medical supplies, arms, tanks, planes, helicopters, artillery, and other military equipment. Soviet ships provided intelligence on B‐52 raids – 3000 soldiers in North Vietnam (Soviet govt. concealed extent of support) • 3.) Chinese supply of anti‐aircraft units and engineering -

Peacelines, Interfaces and Political Deaths in Belfast During the Troubles

Political Geography 40 (2014) 64e78 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Political Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/polgeo Hard to miss, easy to blame? Peacelines, interfaces and political deaths in Belfast during the Troubles Niall Cunningham a,*, Ian Gregory b,1 a CRESC: ESRC Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change, University of Manchester, 178 Waterloo Place, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK b Department of History, Bowland College, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YT, UK abstract Keywords: As Northern Ireland moves further from the period of conflict known as the ‘Troubles’, attention has Belfast increasingly focussed on the social and material vestiges of that conflict; Northern Ireland is still a Troubles deeply-divided society in terms of residential segregation between Catholic nationalists and Protestant Walls unionists, and urban areas are still, indeed increasingly, characterised by large defensive walls, known as GIS ‘ ’ Segregation peacelines , which demark many of the dividing lines between the two communities. In recent years a Violence body of literature has emerged which has highlighted the spatial association between patterns of conflict fatality and proximity to peacelines. This paper assesses that relationship, arguing that previous analyses have failed to fully take account of the ethnic complexity of inner-city Belfast in their calculations. When this is considered, patterns of fatality were more intense within the cores or ‘sanctuaries’ of highly segregated Catholic and Protestant communities rather than at the fracture zones or ‘interfaces’ between them where peacelines have always been constructed. Using census data at a high spatial resolution, this paper also provides the first attempt to provide a definition of the ‘interface’ in clear geographic terms, a spatial concept that has hitherto appeared amorphous in academic studies and media coverage of Belfast during and since the Troubles.