Playing with Words Dav Pilkey's Literary Success in Humorous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Shakespeare: Text Clues 101

Teaching Romeo and Juliet Workshop Saturday, October 26, 2019 Instructor: Kevin Long Teaching Shakespeare: Text Clues 101 ...everyone according to his cue. A Midsummer Night’s Dream Definitions Know exactly what you are saying at all times. Use the Lexicons, Shakespeare’s Words, Shakespeare A to Z, Shakespeare’s Bawdy, and footnotes. Anoint two dueling “Lexicon Masters” each day. Make dictionary work COOL! Verse & Prose Shakespeare is about 75% verse (poetic line form) and 25% prose form. The form of writing might indicate a clue as to the type of character you are playing. Prose is sometimes an indication that the character might be of a lower class, comic or mad, while verse might indicate that your character is of higher class, intelligent, clever, etc. Pay particular attention to when a character switches from poetry to prose and visa versa. This is a major clue from Shakespeare. Verse PRINCE And for that offence Immediately we do exile him hence. I have an interest in your hearts’ proceeding: My blood for your rude brawls doth lie a-bleeding; But I’ll amerce you with so strong a fine That you shall all repent the loss of mine. I will be deaf to pleading and excuses, Nor tears nor prayers shall purchase out abuses: Therefore use none. Let Romeo hence in haste, Else, when he is found, that hour is his last. Bear hence this body, and attend our will: Mercy but murders, pardoning those that kill. Romeo and Juliet, Act 3, scene 1 Prose NURSE Well, you have made a simple choice, you know not how to choose a man: Romeo? no, not he; though his face be better than any man’s, yet his leg excels all men’s, and for a hand and a foot and a body, though they be not to be talked on, yet they are past compare. -

Non-Serious Text Types, Comic Discourse, Humour, Puns, Language Play, Limericks, Punning and Joking Leonhard Lipka

Non-serious Text Types, Comic Discourse, Humour, Puns, Language Play, Limericks, Punning and Joking Leonhard Lipka Text Types, in a broad sense, may be classified, according to the intention of the text- producer, as either serious or not. Another binary distinction is spoken vs. written texts, neutralized in the category discourse. Such classifications may be used in the composition of corpora, where humour is often neglected as a criterion. Basically, word play and joking must be analysed and described from a pragmatic perspective. Keywords: discourse, word-play, humour, pun, pragmatics 1. Text Types and Corpora 1.1 Humour in the ICE, LOB and elsewhere As described in Greenbaum (1991) the detailed composition of the International Corpus of English (ICE) does not contain the class of humorous texts at all. Fries, in his teaching, called jokes, headlines, captions, texts on greeting cards, prefaces, dedications ‘Minor Text Types’. He would also include limericks in this category (personal communication). Another binary classification possible would be if a text is invited or not. Invited texts are e.g. book reviews or contributions to festschrifts or to collections of articles and special volumes and numbers of journals (including online journals – responding to call for papers). In contrast, as shown in Lipka (1999: 90) the Lancaster-Oslo-Bergen (or LOB) Corpus contains only two instances and samples of humour. This observation demonstrates a clear neglect of such an important aspect of human communication. However, various books deal with the phenomenon and provide a wealth of illustrations of verbal play, puns and jokes such as Blake (2007), Chiaro (1992), Crystal (1998), Nash (1985) and Redfern (1984). -

Captain Underpants and the Attack of the Talking Toilets Free Download

CAPTAIN UNDERPANTS AND THE ATTACK OF THE TALKING TOILETS FREE DOWNLOAD Dav Pilkey | 144 pages | 16 Jun 2000 | Scholastic | 9780439995443 | English | London, United Kingdom Captain Underpants and the Attack of the Talking Toilets This book is not my level but it is funny and fun to read. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Captain Underpants in the comic stops and defeats them. Krupp, they turn him into Captain Underpants—the world's most underdressed superhero. These books are becoming my guilty pleasure. They find cafeteria food and use it to fight the Talking Toilets. Universal Conquest Wiki. Paperback Book. To create our March 4,is a popular children's author and artist. Value-priced paper-over-board hardcovers with foil for just Amusing and silly story with lots of gimmicky things to keep the reluctant reader turning the pages. George and Harold see a sign on there way to school it says "second annual invention convention" then suddenly Mr. Now let me talk about the age of my children. After the argument Mr Meaner opens the door to the gym Captain Underpants and the Attack of the Talking Toilets Harold and George told him not to only to him being eaten Captain Underpants and the Attack of the Talking Toilets flushed by a talking man eating toilet. First edition cover. Lolo forgot about the fliporamas Brought back great memories and I laughed the whole time lol. However, Melvin Sneedly breaks his promise and tattles on George and Harold. Is this book interesting or is it to kiddish. That's because they glued Principal Krupp to Captain Underpants and the Attack of the Talking Toilets chair at last year's science fair. -

Approximate Weight of Goods PARCL

PARCL Education center Approximate weight of goods When you make your offer to a shopper, you need to specify the shipping cost. Usually carrier’s shipping pricing depends on the weight of the items being shipped. We designed this table with approximate weight of various items to help you specify the shipping costs. You can use these numbers at your carrier’s website to calculate the shipping price for the particular destinations. MEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 70 - 100 Jacket 1000 - 1200 Sports shirt, T-shirt 220 - 300 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 UnderpantsShirt 70120 - -100 180 JacketWind-breaker 1000800 - -1200 1200 SportsBusiness shirt, suit T-shirt 2201200 - -300 1800 Coat,Autumn duster jacket 9001200 - -1500 1400 Sports suit 1000 - 1300 Winter jacket 1400 - 1800 Pants 600 - 700 Fur coat 3000 - 8000 Jeans 650 - 800 Hat 60 - 150 Shorts 250 - 350 Scarf 90 - 250 UnderpantsJersey 70450 - -100 600 JacketGloves 100080 - 140 - 1200 SportsHoodie shirt, T-shirt 220270 - 300400 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 WOMEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 15 - 30 Shorts 150 - 250 Bra 40 - 70 Skirt 200 - 300 Swimming suit 90 - 120 Sweater 300 - 400 Tube top 70 - 85 Hoodie 400 - 500 T-shirt 100 - 140 Jacket 230 - 400 Shirt 100 - 250 Coat 600 - 900 Dress 120 - 350 Wind-breaker 400 - 600 Evening dress 120 - 500 Autumn jacket 600 - 800 Wedding dress 800 - 2000 Winter jacket 800 - 1000 Business suit 800 - 950 Fur coat 3000 - 4000 Sports suit 650 - 750 Hat 60 - 120 Pants 300 - 400 Scarf 90 - 150 Leggings -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Lost Pigs and Broken Genes: The search for causes of embryonic loss in the pig and the assembly of a more contiguous reference genome Amanda Warr A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh 2019 Division of Genetics and Genomics, The Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has been carried out, and the thesis composed, by the candidate Amanda Warr. Contributions by other individuals have been indicated throughout the thesis. These include contributions from other authors and influences of peer reviewers on manuscripts as part of the first chapter, the second chapter, and the fifth chapter. Parts of the wet lab methods including DNA extractions and Illumina sequencing were carried out by, or assistance was provided by, other researchers and this too has been indicated throughout the thesis. -

The Cognitive Psychology of Humour in Written Puns

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-23-2018 10:00 AM The Cognitive Psychology of Humour in Written Puns James Boylan The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Katz, Albert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Psychology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © James Boylan 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Cognition and Perception Commons, and the Cognitive Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Boylan, James, "The Cognitive Psychology of Humour in Written Puns" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5947. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5947 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The primary purpose of this dissertation was to investigate how humour from written puns is produced. Prior models have emphasized that novel or surprising incongruities should be important for humour appreciation (Suls, 1972; Topolinski, 2014). In study 1, a new approach to operationalizing incongruity as semantic dissimilarity was developed and tested using Latent Semantic Analysis (Landauer, Foltz & Laham, 1998). “Latent semantic incongruity” was associated with humour ratings, but only for puns with low ratings of familiarity from a prior occasion or for those with a low level of aggressive content. Overall, there was also an unexpected strong positive association between familiarity and humour ratings. Study 2 demonstrated that humour ratings for puns decreases with repeated exposures. -

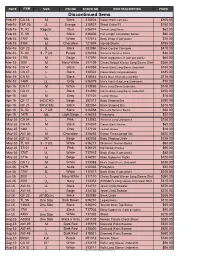

2017 Nefful Product Discontinued List

DATE ITEM SIZE COLOR STOCK NO. ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE 2017 NeffulCO Product Discontinued List Discontinued Items Feb-16 CA 48 M Black 318026 Classic Black Camisole $105.00 Feb-16 DW 05 LL Orange 315937 Shawl Collar PJ $780.00 Feb-16 TL 52 Regular Blue 616074 Teviron Long Socks $62.00 Feb-16 TL 59 L Black 616406 Full Length Circulation Socks $90.00 Feb-16 1707 ML White 717014 Body Wrap (1 per pack) $70.00 Feb-16 3364 M Chocolate 121834 Hip-Up Shorts $155.00 Mar-16 QF 23 3L Black 382094 Black Control Camisole $410.00 Mar-16 TL 02 5 - 7 US Purple 616063 Women's Summer Socks $38.00 Mar-16 1705 M Beige 717091 Wrist supporters (1 pair per pack) $60.00 Mar-16 2001 M Navy-White 317109 Chess Striped Woven Long Sleeve Shirt $360.00 Mar-16 CA 41 M Black 314059 Classic Black Long-Sleeve Undershirt $150.00 Mar-16 CA 47 L Black 318024 Classic Black Long Underpants $185.00 Mar-16 CA 52 L Black 318044 Men's Black Short-Sleeved Shirt $178.00 Mar-16 1489 LL Gray 616079 Men's Tight-Fitting Long Underpants $70.00 Apr-16 CA 11 M White 313085 Men's Long-Sleeve Undershirt $148.00 Apr-16 CA 41 L Black 314060 Classic Black Long-Sleeve Undershirt $150.00 Apr-16 1461 M Gray 717101 Teviron Gloves $18.00 Apr-16 QF 11 36C(C80) Beige 382013 Body Shaping Bra $290.00 Apr-16 QF 21 38C(C85) Black 382064 Black Shaping Bra $315.00 Apr-16 TL 02 5 - 7 US Black 616058 Women's Summer Socks $38.00 Apr-16 1479 ML Light Beige 616033 Pantyhose $30.00 May-16 CA 04 L Pink 313082 Women's Long Underpants $150.00 May-16 CA 45 M Black 314067 Classic Black Panties $65.00 May-16 1461 L -

JEFF KINNEY: Might Act Them Out, Or Even Create Scenarios for the TELLING FUNNY STORIES Different Types of Laughter

SPONSORED BY IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AGES 9-11 NOTES FOR TEACHERS & LIBRARIANS type of laugh that they list – or, better still, they JEFF KINNEY: might act them out, or even create scenarios for the TELLING FUNNY STORIES different types of laughter. Ask students to share their different types of laughter with their classmates. Are they ready to snigger, giggle or snort when they watch Jeff’s video? AFTER WATCHING THE VIDEO AND READING THE EXTRACT: DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Do you think the series title Diary of a Wimpy Kid is a funny title? Why? 2. What is effective about using the form of adiary to document Greg’s adventures? Do you like this format? Why? How does it change the experience BEFORE WATCHING THE VIDEO AND of reading? READING THE EXTRACT: 3. Jeff Kinney often uses words made up of capital GET IN THE ZONE! letters in his writing. Can you find any examples of this in the extract? What is the effect of using The Diary of a Wimpy Kid series by Jeff Kinney capital letters? What do they show? is well-known for its humour and ability to make people laugh. 4. Can you find an example ofonomatopoeia in the extract? Why is this an effective technique for A good way to get students in the right frame creating comedy? of mind for telling funny stories is to get them thinking about laughter. Ask them to consider the 5. How does Jeff Kinney present the relationship following questions in pairs: What is laughter? between Greg and his parents in the extract from When do we laugh? Why is it important? When Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Meltdown? Why is was the last time you really laughed? this funny? Then, ask students to list as many types of laughs 6. -

Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric Paul Butler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Butler, Paul, "Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric" (2008). All USU Press Publications. 162. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/162 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 6679-0_OutOfStyle.ai79-0_OutOfStyle.ai 5/19/085/19/08 2:38:162:38:16 PMPM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K OUT OF STYLE OUT OF STYLE Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric PAUL BUTLER UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2008 Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-87421-679-0 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-680-6 (e-book) “Style in the Diaspora of Composition Studies” copyright 2007 from Rhetoric Review by Paul Butler. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group, LLC., http:// www. informaworld.com. Manufactured in the United States of America. Cover design by Barbara Yale-Read. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Butler, Paul, Out of style : reanimating stylistic study in composition and rhetoric / Paul Butler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

A Stylistic Approach to the God of Small Things Written by Arundhati Roy

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of English 2007 A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy Wing Yi, Monica CHAN Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chan, W. Y. M. (2007). A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14793/eng_etd.2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY CHAN WING YI MONICA MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2007 A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY by CHAN Wing Yi Monica A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in English Lingnan University 2007 ABSTRACT A Stylistic Approach to The God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy by CHAN Wing Yi Monica Master of Philosophy This thesis presents a creative-analytical hybrid production in relation to the stylistic distinctiveness in The God of Small Things, the debut novel of Arundhati Roy. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Discourse Types in Stand-Up Comedy Performances: an Example of Nigerian Stand-Up Comedy

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2015.3.1.filani European Journal of Humour Research 3 (1) 41–60 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Discourse types in stand-up comedy performances: an example of Nigerian stand-up comedy Ibukun Filani PhD student, Department of English, University of Ibadan [email protected] Abstract The primary focus of this paper is to apply Discourse Type theory to stand-up comedy. To achieve this, the study postulates two contexts in stand-up joking stories: context of the joke and context in the joke. The context of the joke, which is inflexible, embodies the collective beliefs of stand-up comedians and their audience, while the context in the joke, which is dynamic, is manifested by joking stories and it is made up of the joke utterance, participants in the joke and activity/situation in the joke. In any routine, the context of the joke interacts with the context in the joke and vice versa. For analytical purpose, the study derives data from the routines of male and female Nigerian stand-up comedians. The analysis reveals that stand-up comedians perform discourse types, which are specific communicative acts in the context of the joke, such as greeting/salutation, reporting and informing, which bifurcates into self- praising and self denigrating. Keywords: discourse types; stand-up comedy; contexts; jokes. 1. Introduction Humour and laughter have been described as cultural universal (Oring 2003). According to Schwarz (2010), humour represents a central aspect of everyday conversations and all humans participate in humorous speech and behaviour. This is why humour, together with its attendant effect- laughter, has been investigated in the field of linguistics and other disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology and anthropology.