The Neo-Vaishnavite Movement of Assam Unit 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposal Under Demand No-07-3054-04-337-0865-21007'District Head Quarter Road for the Year 2019-20 SI

Proposal under Demand No-07-3054-04-337-0865-21007'District Head Quarter Road for the year 2019-20 SI. Name of the Amount Name of the Work No. (R&B) Division (Rs. In lakh) 1 2 3 4 S/R to New Jagannath Sadak from 0/630 to Q/660km ( Such as providing 1 Puri 4.76 Cement Concrete pavement at Chandanpur Bazar Portion ) S/R to New Jagannath Sadak from 0/665 to 0/695km ( Such as providing 2 Puri 4.91 Cement Concrete pavement at Chandanpur Bazar Portion ) Construction of entry gate on approach to Makara Bridge at ch,23/80km of New 3 Puri 4.23 Jagannath Sadak, Puri S/r ro New Jagannath Sadak from 14/070 to 14/240 Km such as construction of 4 Puri 4.82 Toe-wall & Packing on right side Construction of Retaining wall in U/S of Ratnachira Bridge at 13/290Km of New 5 Puri 4.98 Jagannath Sadak 6 Puri S/R to Jagannath Sadak road {Such as construction of Toe-wall at 2/300 Km) 4.74 Providing temporary Bus parking at Chupuring & approach road to Melana 7 Puri padia Jankia Gadasahi near New Jagannath Sadak for the visit of Hon’ble Chief 2.57 Minister of Odisha on 20.02,2019 Providing temporary Helipad ground Jankia Gadasahi near New Jagannath 8 Puri 3.00 Sadak for the visit of Hon'ble Chief Minister of Odisha on 20.02.2019 Providing temporary parking at Jankia Gadasahi near New Jagannath Sadak for 9 Puri 2.41 the visit of Hon'ble Chief Minister of Odisha on 20.02.2019 Providing temporary parking at Kanas side & Gadasahi near New Jagannath 10 Puri 4.88 Sadak for the visit of Hon'ble Chief Minister of Odisha on 20.02.2019 Repair of road from Hotel Prachi to -

Indian Cultural Dance Logos Free Download Indian Cultural Dance Logos Non Watermarked Dance

indian cultural dance logos free download indian cultural dance logos non watermarked Dance. Information on North Central Zonal Cultural Centre (NCZCC) under the Ministry of Culture is given. Users can get details of various art forms of various states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Uttaranchal and Delhi. Get detailed information about the objectives, schemes, events of the centre. Links of other zonal cultural centers are also available. Website of Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre. The Eastern Zonal Cultural Center (EZCC) is one of the seven such Zonal Cultural Centers set up by the Ministry of Culture with a vision to integrate the states and union territories culturally. Users can get information about the objectives, infrastructure, events, revival projects, etc. Details about the member states and their activities to enhance the cultural integrity are also available. Website of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) under the Ministry of Culture is functioning as a centre for research, academic pursuit and dissemination in the field of the arts. Information about IGNCA, its organizational setup, functions, functional units, regional centres, etc. is given. Details related to archeological sites, exhibitions, manuscripts catalogue, seminars, lectures. Website of Jaipur Kathak Kendra. Jaipur Kathak Kendra is a premier Institution working for Training, Promotion & Research of North Indian Classical Dance Kathak. It was established in the year 1978 by the Government of Rajasthan and formally started working from 19th May 1979. Website of North East Zone Cultural Centre. North East Zone Cultural Centre (NEZCC) under Ministry of Culture aims to preserve, innovate and promote the projection and dissemination of arts of the Zone under the broad discipline of Sangeet Natak, Lalit Kala and Sahitya. -

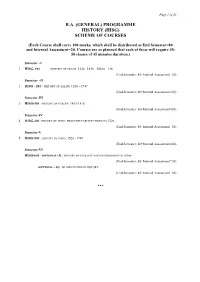

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Assam - a Study on Bihugeet in Guwahati (GMA), Assam

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Impact Factor (2018): 7.426 Female Participation in Folk Music of Assam - A Study on Bihugeet in Guwahati (GMA), Assam Palme Borthakur1, Bhaben Ch. Kalita2 1Department of Earth Science, University of Science and Technology, Meghalaya, India 2Professor, Department of Earth Science, University of Science and Technology, Meghalaya, India Abstract: Songs, instruments and dance- the collaboration of these three ingredients makes the music of any region or society. Folk music is one of the integral facet of culture which also poses all the essentials of music. The instruments used in folk music are divided into four halves-taat (string instruments), aanodha(instruments covered with membrane), Ghana (solid or the musical instruments which struck against one another) and sushir(wind instruments)(Sharma,1996). Out of these four, Ghana and sushirvadyas are being preferred to be played by female artists. Ghana vadyas include instruments like taal,junuka etc. and sushirvadyas include instruments that can be played by blowing air from the mouth like flute,gogona, hkhutuli etc. Women being the most essential part of the society are also involved in the process of shaping up the culture of a region. In the society of Assam since ancient times till date women plays a vital role in the folk music that is bihugeet. At times Assamese women in groups used to celebrate bihu in open spaces or within forest areas or under big trees where entry of men was totally prohibited and during this exclusive celebration the women used to play aforesaid instruments and sing bihu songs describing their life,youth and relation with the environment. -

The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, Pp 232

Book Discussion Dilip K Chakrabarti: The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, pp 232 Understanding Indian Borderlands Dilip K Chakrabarti he Indian subcontinent shares borders with Iran, Afghanistan, the plateau of Tibet Tand Myanmar. The sub-continent’s influence extends beyond these borders, creating distinct ‘borderlands’ which are basically geographical, political, economic and religious interaction zones. It is these ‘borderlands’ which historically constitute the subcontinent’s ‘area of influence’ and underlines its civilizational role in the Asian landmass. A clear understanding of this civilizational role may be useful in strengthening India’s perception of her own geo-strategic position. Iran One may begin with Iran at the western limit of these borderland. There are two main mountain ranges in Iran : the Zagros which separates Iran from Iraq and has to its south the plain of Khuzestan giving access to south Iraq ; and the Elburz which separates the inland Iran from the Caspian belt, Turkmenistan and (to a limited extent , Azerbaijan). The Caspian shores form a well-wooded verdant belt which poses a strong contrast to the dry Iranian plateau. There are two deserts inside the Iranian plateau -- dasht-i-lut and dasht-i-kevir, which do not encourage human habitation. The population concentration of Iran is along the margins of the mountain belt and also in Khuzestan. The following facts are noteworthy. The eastern rim of Iran carries an imprint of the subcontinent. There is a ready access to Iranian Baluchistan through the Kej valley in Pakistani Baluchistan. At its eastern edge this valley leads both to lower Sindh and Kalat. -

The Divine Name

THE DIVINE NAME by Raghava Chaitanya Das Published by BHAKTI VIGYAN NITYANANDA BOOK TRUST SRI KRISHNA CHAITANYA MISSION (Regd.) SRI BHAKTI VINOD ASHRAM BERHAMPUR-6(GM) (INDIA) SRI GAUR JAYANTI 24 March 1997 (WWW Edition - Vamana dvadasi 2007) All Rights Reserved By BHAKTI VIGYAN NITYANANDA BOOK TRUST CONTENTS PREFACE........................................................................................................9 DIVINE NAME AND ITS EFFICACIES.................................................................14 DIVINE NAME - THE SWEETEST OF ALL..........................................................................................14 DIVINE NAME - THE SOLE REMEDY FOR ALL ILLS...............................................................................15 DIFFERENT DIVINE DISPENSATIONS..............................................................................................15 DIVINE NAME - THE BEST IN KALI YUGA.......................................................................................16 AGE OF MACHINES................................................................................................................16 AGE OF FREE CONTROVERSY......................................................................................................17 ABODES OF KALI..................................................................................................................17 DIVINE GRACE - ESSENTIAL......................................................................................................18 SELF-SURRENDER - WAY -

Magazine-2-3.Qxd (Page 2)

SUNDAY, AUGUST 30, 2015 (PAGE-3) SACRED SPACE BOOK REVIEW Upanishads Rediscovering Hinduism in the Himalayas Surinder Koul sacerdotal rites. Description about several obliterated sculptures of Source of Spirituality Albeit, the writer is professionally medical doctor, who often trav- images of Hindu Goddess and Gods , carved pillars, floral designs els to Arunachal Pradesh, the remotest part of the country and other on plinth slabs, full lotus carved on circular stone slab in Malinithan R C Kotwal Rajasthan and M.P. of present day India. places, out of her inquisitiveness and yearning to study cultural and temple premises are mentioned in minute details . Book also car- The exact numbers of the Upanishads are not clearly architectural sites in the country, yet she has produced the book as ries out various performances of worshipping that was prevalent in Upanishads means the inner or mystic teaching. The term known. Scholars differ on the total number of Upanishads as an intellectual fallow for interested people to undertake further deep main land India among the Hindus and had been practiced by the research about cultural heritage, sociological and environmental people in Arunachal Pradesh also from ages. It has identified tem- "Upanishad" is derived from Upa(Near) , ni ( down) and shad well as what constitutes an Upanishad. Some of the Upan- (to sit) i.e sitting down near. Groups of pupils sit near the aspects of earlier called NEFA now lately rechristened as Arunachal ples precincts and ruins where worshipping of Shiva Linga, worship- ishads are very ancient, but some are of recent origin. Pradesh. This region Arunachal Pradesh, had remained neglected ping of Durga as Malini still exist and on auspicious occasion devo- teacher to learn from him the secret doctrine. -

Hindutva Paper

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Power of Persuasion Citation for published version: Longkumer, A 2017, 'The Power of Persuasion: Hindutva, Christianity, and the discourse of religion and culture in Northeast India', Religion, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 203-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Religion Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Religion on 7/12/2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 The Power of Persuasion: Hindutva, Christianity, and the discourse of religion and culture in Northeast India.1 Abstract: The paper will examine the intersection between Sangh Parivar activities, Christianity, and indigenous religions in relation to the state of Nagaland. I will argue that the discourse of ‘religion and culture’ is used strategically by Sangh Parivar activists to assimilate disparate tribal groups and to envision a Hindu nation. -

The Classical Tradition in the Vaisnava Music of Assam

The Classical Tradition in the Vaisnava Music of Assam Maheswar Neog --- www.atributetosankaradeva.org presents before the readers a pioneering paper on the Vaisnava music of Assam, authored by Dr. Maheswar Neog. It covers virtually every aspect of the music of the Sankaradeva Movement (and also touches upon other traditions of music in Assam). As is evidenced by some of its references, this paper was written in the early part of the latter half of the 20th century when Bargit research was still at a nascent stage. We have retained these references as they reflect the important milestones in the progress of research on the Sankaradeva Movement in Assam. The paper is redacted from the Journal of the Srimanta Sankaradeva Research Institute, Nagaon (2006). Editing note(s):- Diacritics has been used sparingly; only the long diacritic (macron) pertaining to a/A has been highlighted and that too, depending upon the context. --- We do not have any particular evidence to show what exact type of music was prevalent in Assam anterior to the spread of the wave of neo-Vaisnavism which was ushered into the valley of the Brahmaputra in the last decades of the 15th and the initial decades of the 16th century by Sankaradeva. We are left to our imagination in this matter; but this imagination can be based on the evidence of the writings of a few pre- Sankaradeva poets, and the song compositions of at least two poets, Mankara and Durgavara, who seem to have remained outside of the neo-Vaisnava circle of Sankaradeva. In the early period of Assamese literature preceding the neo-Vaisnava movement of the last part of the 15th century and the early part of the 16th, the Ramayana and portions of the Mahabharata were rendered into Assamese verse; and these verses were put to ragas or recited in simple tunes. -

Download Itinerary

Starting From Rs. 14102.4 (Per Person twin sharing) PACKAGE NAME : No 11 North East Triangle PRICE INCLUDE Hotel,Only Breakfast,Activity,Sightseeing,Car On Disposal Day : 1 Guwahati - Kaziranga National Park (230 KM 4.5 Hrs) Welcome to Guwahati. Meet and be assisted by our representative at the airport/Railway Station. Transfer to Kaziranga National Park, the home of the One Horn Indian Rhinoceros. Check in at your hotel/Lodge/resort. Evening you may visit Orchid Park and the nearby Tea Plantations. Overnight stay at Kaziranga National Park. HOTEL Florican Lodge SIGHTSEEING Orchid Park Day : 2 Kaziranga National Park Early morning explore Kaziranga National Park on back of elephant. Apart from world's endangered One Horn Indian Rhinoceros, the Park sustains half the world's population of genetically pure Wild Water Buffaloes, over 1000 Wild elephants and perhaps the densest population of Royal Bengal Tiger anywhere. Kaziranga National Park is also a bird watcher's paradise and home to some 500 species of Birds. The Crested Serpent Eagle, Palla's Fishing Eagle, Greyheaded Fishing Eagle, Swamp Partridge, Bar-headed goose, whistling Teal, Bengal Florican, Storks, Herons and Pelicans are some of the species found here. We will return to the resort for breakfast. Afternoon we proceed for a jeep safari. Evening come back to the hotel. Overnight stay at Kaziranga National Park. HOTEL Florican Lodge SIGHTSEEING Elephant Safari (Kaziranga), Jeep Safari (Kaziranga) Day : 3 Kaziranga National Park– Shillong (280 Km | 6 Hrs) After breakfast drive to Shillong, also called 'Scotland of the East". Reach the majestic Umium Lake (Barapani). -

Renaissance in Assamese Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 3 Issue 9 ǁ September. 2014 ǁ PP.45-47 Renaissance in Assamese Literature Dr. Chandana Goswami Associate Professor Dept. of History D.H.S.K. College Dibrugarh, Assam, India ABSTRACT : The paper entitled “Renaissance in Assamese Literature” attempts to highlight the growing sense of consciousness in the minds of the Assamese people. From 1813 to 1854, the year of Wood’s Despatch, this was the period when Assam was experiencing the beginning of a new phase of national life, being thrown into contact with the west. It was trade that had already brought the British salt merchants into Assam. When finally the British took over Assam it had been suffering for a long period from internal disturbances which were closely followed by the Burmese invasions. Education in the country in the early years of British rule was in a retrograde state. In 1837 when Bengali replaced the Assamese as the language of the court, the missionaries had just arrived in Assam. They took up cudgels against the imposition of the Bengali language. The near total darkness shrouding Assam from the outside world was gradually removed with the entry of the British who gradually broke Assam’s isolation by establishing new routes of communication. The educated elite of the time contributed largely towards the development of Assamese literature. I. INTRODUCTION : The term “renaissance” was first used in a specific European context, to describe the great era from about the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries, when the entire socio-cultural atmosphere of Europe underwent a spectacular transformation.