Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

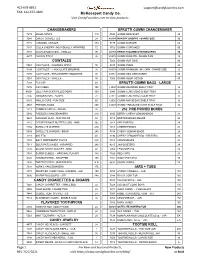

Mckeesport Candy Co. CANDY CIGARETTES & CIGARS

412-678-8851 [email protected] FAX: 412-673-4406 McKeesport Candy Co. Visit CandyFavorites.com to view products. *** Please note that website prices reflect suggested retail *** CHANGEMAKERS EFRUTTI GUMMI CHANGEMAKER 7272 ANGEL MINTS 110 4090 GUMMI BRACELET 40 7248 CANDY CIGARETTES 24 42134 BAKERY SHOPPE - SHARE SIZE 12 7171 CARAMEL CREAMS 170 7177 GUMMI BURGER 60 7347 CELLA CHERRY- INDIVIDUALLY WRAPPED 72 3752 GUMMI CUPCAKES 60 7173 CHARLSTON CHEW - VANILLA 96 42133 EFRUTTI GUMMI CHEESECAKES 30 4277 CHICKO STICK 36 40078 GUMMI DONUTS - SHARE SIZE 12 COWTALES 7262 GUMMI HOT DOG 60 5067 COWTALES - CARAMEL APPLE 36 4105 GUMMI PIZZA 48 5304 COWTALES - CHOCOLATE BROWNIE 36 40079 GUMMI RAINBOW UNICORN - SHARE SIZE 12 7270 COWTALES - STRAWBERRY SMOOTHIE 36 63151 GUMMI SEA CREATURES 60 7263 COWTALES - VANILLA 36 7266 GUMMI SOUR GECKO 40 7269 FUN DIP 48 EFRUTTI GUMMI BAGS - LARGE 7275 ICE CUBES 100 43030 GUMMIUNIVERSE SHELF TRAY 12 46001 JOLLY RANCHER FILLED POPS 100 6943 GUMMI LUNCH BAG SHELF TRAY 12 7286 JUNIOR MINTS - BOXES 72 42111 GUMMI LUNCH BAG SOUR TRAY 12 5443 MALLO CUPS - FUN SIZE 60 42008 GUMMI MOVIE BAG SHELF TRAY 12 4848 PRETZEL RODS 450 43203 GUMMI TREASURE HUNT SHELF TRAY 12 7313 PUMPKIN SEEDS - INDIAN 36 25¢ PRE-PRICED BOXES 5040 RAZZLES CHANGEMAKERS 240 3395 BERRY CHEWY LEMONHEADS 24 4423 RAIN-BLO GUM - MINI PACKS 48 4018 BOSTON BAKED BEANS 24 7215 REESE PEANUT BUTTER CUPS - MINI 105 7912 APPLEHEADS 24 7156 SATELLITE WAFERS 240 7913 CHERRYHEADS 24 5089 SATELLITE WAFERS - SOUR 240 5154 CHEWY LEMONHEADS 24 7318 SIXLETS -

Counterculture Brian Rande Daykin University of Maine - Main

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 2001 Counterculture Brian Rande Daykin University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Daykin, Brian Rande, "Counterculture" (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 46. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/46 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. COUNTERCULTURE BY Brian Rande Daykin B.A. University of Michigan, 1995 ATHESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in English) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2001 Advisory Committee: Elaine Ford, Professor of English, Advisor Welch Everman, Professor of English Naomi Jacobs, Professor of English 0 2001 Rande Daykin All Rights Reserved COUNTERCULTURE By Rande Daykin Thesis Advisor: Elaine Ford An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in English) May, 2001 Counterculture is a creative thesis written to earn the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Maine in spring of 2001. The short novel tells the story of Cannister Barnes, a young man who goes to England in the late summer for study and briefly catches a glimpse of a young woman while he’s lost in the winding streets and paths of Eton. His trip is also marred by a dreadful experience in the London Underground, in which he sees an indigent man in a wheelchair roll himself into the path of an oncoming train. -

A Stylistic Approach to the God of Small Things Written by Arundhati Roy

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of English 2007 A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy Wing Yi, Monica CHAN Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chan, W. Y. M. (2007). A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14793/eng_etd.2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY CHAN WING YI MONICA MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2007 A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY by CHAN Wing Yi Monica A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in English Lingnan University 2007 ABSTRACT A Stylistic Approach to The God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy by CHAN Wing Yi Monica Master of Philosophy This thesis presents a creative-analytical hybrid production in relation to the stylistic distinctiveness in The God of Small Things, the debut novel of Arundhati Roy. -

Explorations the Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities for the State of North Carolina

Volume VI, 2011 Explorations The Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities for the State of North Carolina www.uncw.edu/csurf/explorations.html [email protected] Center for the Support of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships UNCW Honors College Randall Library University of North Carolina Wilmington Wilmington, NC 28403 copyright © 2011 University of North Carolina Wilmington Cover photographs: “Smoky Mountain Sunset” © Frank Kehren “Sunset Poplar” © BlueRidgeKitties “Outer Banks” © Patrick McKay ISBN: 978-0-9845922-7-2 Original Design by The Publishing Laboratory Department of Creative Writing 601 South College Road Wilmington, North Carolina 28403 www.uncw.edu/writers Dedication George Timothy Barthalmus (October 27, 1942- May 12, 2011) We lost our good friend George last spring. He was the inspiration behind Explorations and the State of North Carolina Undergraduate Research and Creativity Symposium, SNCURCS. George was known for his outreach to and support of student researchers- indeed, we feel he was the champion for undergraduate research in our state. We miss his infectious smile and bright, engaging eyes, his energy and excitement. Our hearts go out to his family, and we are glad for the time we shared with him. Volume VI of Explorations is dedicated to the memory of George Barthalmus. Photo courtesy of http://www.ncsu.edu/faculty-and-staff/bulletin/2011/05/students-colleagues- remember-barthalmus/ Staff Editor-in-Chief Katherine E. Bruce, PhD Director, Honors College and Center for the Support of Undergraduate -

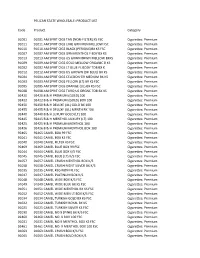

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

Campbell Wholesale Company, Inc. Order Book 6849 E

Campbell Wholesale Company, Inc. Order Book 6849 E. 13th 1104 W. Broadway Tulsa, Oklahoma 74112 Muskogee, Oklahoma 74401 1(800) 722-2359 1(888) 516-2997 (918) 836-8774 (918) 682-6608 Fax: (918) 832-5689 Fax: (918) 686-8182 Customer No.: ________________________________________________ Customer Name: _____________________________________________ Date: _________________________________________________________ Written By: ___________________________________________________ ITEM NO. QTY. DESCRIPTION ITEM NO. QTY. DESCRIPTION _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ -

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~. -

Master Candy List

412-678-8851 [email protected] FAX: 412-673-4406 McKeesport Candy Co. Visit CandyFavorites.com to view products. CHANGEMAKERS EFRUTTI GUMMI CHANGEMAKER 7272 ANGEL MINTS 110 4090 GUMMI BRACELET 40 7248 CANDY CIGARETTES 24 42134 BAKERY SHOPPE - SHARE SIZE 12 7171 CARAMEL CREAMS 170 7177 GUMMI BURGER 60 7347 CELLA CHERRY- INDIVIDUALLY WRAPPED 72 3752 GUMMI CUPCAKES 60 7173 CHARLSTON CHEW - VANILLA 96 42133 EFRUTTI GUMMI CHEESECAKES 30 4277 CHICKO STICK 36 40078 GUMMI DONUTS - SHARE SIZE 12 COWTALES 7262 GUMMI HOT DOG 60 5067 COWTALES - CARAMEL APPLE 36 4105 GUMMI PIZZA 48 5304 COWTALES - CHOCOLATE BROWNIE 36 40079 GUMMI RAINBOW UNICORN - SHARE SIZE 12 7270 COWTALES - STRAWBERRY SMOOTHIE 36 63151 GUMMI SEA CREATURES 60 7263 COWTALES - VANILLA 36 7266 GUMMI SOUR GECKO 40 7269 FUN DIP 48 EFRUTTI GUMMI BAGS - LARGE 7275 ICE CUBES 100 43030 GUMMIUNIVERSE SHELF TRAY 12 46001 JOLLY RANCHER FILLED POPS 100 6943 GUMMI LUNCH BAG SHELF TRAY 12 7286 JUNIOR MINTS - BOXES 72 42111 GUMMI LUNCH BAG SOUR TRAY 12 5443 MALLO CUPS - FUN SIZE 60 42008 GUMMI MOVIE BAG SHELF TRAY 12 4848 PRETZEL RODS 450 43203 GUMMI TREASURE HUNT SHELF TRAY 12 7313 PUMPKIN SEEDS - INDIAN 36 25¢ PRE-PRICED BOXES 5040 RAZZLES CHANGEMAKERS 240 3395 BERRY CHEWY LEMONHEADS 24 4423 RAIN-BLO GUM - MINI PACKS 48 4018 BOSTON BAKED BEANS 24 7215 REESE PEANUT BUTTER CUPS - MINI 105 7912 APPLEHEADS 24 7156 SATELLITE WAFERS 240 7913 CHERRYHEADS 24 5089 SATELLITE WAFERS - SOUR 240 5154 CHEWY LEMONHEADS 24 7318 SIXLETS 48 3396 CHEWY LEMONHEADS - REDRIFIC 24 7154 SOFT PEPPERMINT PUFFS -

Large Whale Restraint – Page 1 of 108 REPORT of LARGE WHALE

Large Whale Restraint – Page 1 of 108 REPORT OF LARGE WHALE RESTRAINT WORKSHOP Feb 7th & 8th 2006 AT CARRIAGE HOUSE WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION WOODS HOLE MA 02543 SPONSORED BY NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE Order # EM133F05SE5824 Requisition/ Reference # NFFM5100-5-00800 AUTHORS Andrea Bogomolni1, Regina Campbell-Malone1, Nadine Lysiak1 and Michael Moore2 1Rapporteurs, 2Chair Biology Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Woods Hole MA 02543 Large Whale Restraint – Page 2 of 108 Executive Summary The Problem: until large whale entanglements can be avoided, disentanglement is a necessary stop gap measure to enhance the survival of critically endangered large whales. Cases that are refractory to the standard protocols developed and used by the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies (PCCS) are especially head and flipper wraps in right whales. There is a need both for immediately deployable solutions and development of better technology and techniques. Such advances must avoid proliferation of at sea personnel and include plans for next steps in each possible contingency. These are not currently supported within the Disentanglement Network or NOAA. History: two prior workshops resulted in a focus on the potential for sedation to enhance tractability, the delivery of hyper-concentrated Meperidine and Midazolam via a pole delivered, gas powered syringe to an entangled right whale, the acquisition of a working right whale tail model and its use to develop tail harness systems, and the conceptualization of a suction cup tag that could deliver drugs on demand and monitor the status of the individual. Experience from sedating marine mammals in captivity, and observation of sleeping right whales suggests that adequate tractability might be achieved in free swimming animals without significant loss of equilibrium. -

A Portrait My Mentor

PACIFIC UNION COLLEGE JANUARY 2015 A PORTRAIT^ ] OF MY MENTOR Six stories of guidance & inspiration A Home on Mentoring Goes Friendships and Mana Island 04 Mobile 08 Faith 15 PACIFIC UNION COLLEGE • JANUARY 2015 president’s message STAFF Editor Cambria Wheeler, ’08 [email protected] Layout and Design Haley Wesley A Campus Built for Mentorship [email protected] Art Director Cliff Rusch, ’80 [email protected] Walk across campus during any school day and Most of all, this dedication means that students Photographers Allison Regan, ’15; Haley you’ll see the incredible teaching and learning that are known, remembered, and prayed for by their Wesley; Mackenzie White, ’17. happens at Pacific Union College. I don’t refer to teachers in all disciplines. These prayers can result Contributors David Bell; Herb Ford, ’54; the classrooms (though of course, it happens there), in wonderful blessings such as the baptism of Sonia Lee Ha, ’92; Scott Herbert; Michael Lawrence, ‘17; Emily Mathe, ’16; Amanda but the offices. With open doors and comfortable sisters Crystal and Tina Lin last year. Through the Navarrete, ’15; Darin West, ’11; Midori chairs, professors invite students in to meet with mentorship of faculty and the PUC Church com- Yoshimura, ’12. them one-on-one every day. While the students munity, these two students chose to dedicate their PUC ADMINISTRATION stop by to ask questions about the subject matter lives to Christ (see page 15). in their classes, just as often they go to their profes- President Heather J. Knight, Ph.D. sors for conversations about life, about faith, and With the highest on-campus enrollment in 19 Vice President for Academic Administration “It is important Nancy Lecourt, Ph.D. -

Enter the Cube by Nicholas and Daniel Dobkin January 2002 to December 2004

Enter the Cube by Nicholas and Daniel Dobkin January 2002 to December 2004 Table of Contents: Chapter 1: Playtime, Paytime ..............................................................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Not in Kansas Any More....................................................................................................................................6 Chapter 3: A Quiz in Time Saves Six................................................................................................................................18 Chapter 4: Peach Pitstop....................................................................................................................................................22 Chapter 5: Copter, Copter, Overhead, I Choose Fourside for my Bed...........................................................................35 Chapter 6: EZ Phone Home ..............................................................................................................................................47 Chapter 7: Ghost Busted....................................................................................................................................................58 Chapter 8: Pipe Dreams......................................................................................................................................................75 Chapter 9: Victual Reality................................................................................................................................................102 -

EXPLORING the HIDDEN CURRICULUM WITHIN a DOCTORAL PROGRAM a Dissertation Submitted To

“IT’S NOT ALWAYS WHAT IT SEEMS”: EXPLORING THE HIDDEN CURRICULUM WITHIN A DOCTORAL PROGRAM A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College and Graduate School of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Rachel Elizabeth Foot August, 2017 © Copyright, 2017 by Rachel E. Foot All Rights Reserved ii A dissertation written by Rachel E. Foot B.A. (Hons), University of the West of England, 2000 M.Sc., Clarion University, 2003 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by __________________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Alicia R. Crowe __________________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Joanne Kilgour Dowdy __________________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Tricia Niesz Accepted by __________________________________, Director, School of Teaching, Learning Alexa L. Sandmann and Curriculum Studies __________________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health James C. Hannon and Human Services iii FOOT, RACHEL, E. Ph.D., August 2017 TEACHING, LEARNING AND CURRICULUM STUDIES “IT’S NOT ALWAYS WHAT IT SEEMS”: EXPLORING THE HIDDEN CURRICULUM WITHIN A DOCTORAL PROGRAM (pp. 315) Dissertation Director: Alicia R. Crowe Ph.D. The purpose of this qualitative, naturalistic study was to explore the ways in which hidden curriculum might influence doctoral student success. Two questions guided the study: (a) How do doctoral students experience the hidden curriculum? (b) What forms of hidden curricula can be identified in a PhD program? Data were collected from twelve doctoral students within a single program at one university. Participants took part in three sets of semi-structured interviews and data were analyzed using a cross-case analysis. Findings suggest that doctoral students experience mixed messages related to the values and norms of the program when the intended, explicit curriculum is contradicted by a hidden curriculum.