Zanthoxylum Americanum Mill., Rutaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

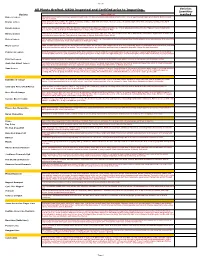

Tomorrow's Harverst Variety Info Common Name

Tomorrow's Harverst Variety Info Common Name Botanical Name Variety Description Chill Pollinator Ripens Flesh Ornamental citrus tree with distinctive aroma under dense canopy of leaves. AKA the Key Lime Citrus aurantiifolia Bartender's lime. No chill required No pollinator required Classic aromatic, green fruit grows well in contianers. Excellent specimen plant. Fragrant Mexican Lime Citrus aurantiifolia Unlikespring blooms.other citrus fruit, the sweetest part of the kumquat is the peel. Ripe fruit is stored No chill required No pollinator required on the tree! Pick whenever you feel like a great tasting snack. Yields little fruits to pop Nagami Kumquat Citrus fortunella 'Nagami' right into your mouth. No chill required No pollinator required Kaffir Lime Citrus hystrix Unique bumpy fruits are used in Thai cooking. Zest of rind or leaves are used. No chill required No pollinator required Best in patio containers, evergreen foliage and fragrant flowers. Harvest year round in Kaffir Dwarf Lime Citrus hystrix Dwarf frost free areas. No chill required No pollinator required Bearss Lime Citrus latifolia Juicy, seedless fruit turns yellow when ripe. Great for baking and juicing. No chill required No pollinator required Yellow flesh Eureka Lemon Citrus limon 'Eureka' Reliable, consistent producer is most common market lemon. Highly acidic, juicy flesh. No chill required No pollinator required Classic market lemon, tart flavor, evergreen foliage and fragrant flowers. Vigorous Eureka Dwarf Lemon Citrus limon 'Eureka' Dwarf productive tree. No chill required No pollinator required Lisbon Lemon Citrus limon 'Lisbon' Productive, commercial variety that is heat and cold tolerant. Harvest fruit year round. No chill required No pollinator required Meyer Improved Lemon Citrus limon 'Meyer Improved' Hardy, ornamental fruit tree is prolific regular bearer. -

Zamia Pumila L. Coontie

VWYZ genera Layout 1/31/08 1:11 PM Page 1178 Z Zamiaceae—Sago-palm family Zamia pumila L. coontie W. Gary Johnson Mr. Johnson retired from the USDA Forest Service’s National Seed Laboratory Synonyms. Zamia angustifolia Jacq., Z. debilis Ait., cm long, and often clustered 2 to 5 per plant. The female Z. floridana A. DC., Z. integrifolia Ait., Z. latifoliolata cones are elongate-ovoid, up to 5 to 19 cm long (LHBH Preneloup, Z. media Jacq., Z. portoricensis Urban, Z. silvi- 1976; FNAEC 1993). The period of receptivity and matura- cola Small, and Z. umbrosa Small. tion of seed is December to March (FNAEC 1993). Insects Other common names. Florida arrowroot, sago (usually beetles or weevils) pollinate coontie. Good seed set [palm] cycad, comptie, Seminole-bread. is helped by hand-pollination (Dehgan 1995). Growth habit, occurrence, and use. Coontie is a Collection of cones, extraction, and storage. Two cycad (a low, palm-like plant) with the trunk underground or seeds are produced per cone scale. The seeds are drupe-like, extending a short distance above ground. It is native to bright orange, 1.5 to 2 cm long (FNAEC 1993). The seeds Georgia, Florida, and the West Indies and is found in may be collected from dehiscing cones in the winter pine–oak woodlands and scrub, and on hammocks and shell (January in Gainesville, Florida). The pulpy flesh should be mounds. About 30 Zamia species are native to the American partially dried by spreading out the seeds to air-dry for tropics and subtropics. Zamia classification in Florida has about a month. -

Topic: Apomixis - Definition and Types

Course Teacher: Dr. Rupendra Kumar Jhade, JNKVV, College of Horticulture,Chhindwara(M.P.) B.Sc.(Hons) Horticulture- 1st Year, II Semester 2019-20 Course: Plant Propagation and Nursery Management Lecture No. 12 Topic: Apomixis - Definition and types Apomixis, derived from two Greek word “APO” (away from) and “MIXIS” (act of mixing or mingling). The first discovery of this phenomenon is credited to Leuwen hock as early as 1719 in Citrus seeds. In apomixes, seeds are formed but the embryos develop without fertilization. The genotype of the embryo and resulting plant will be the same as the seed parent. Definition: “The process of development of diploid embryos without fertilization.” Or “Apomixis is a form of asexual reproduction that occurs via seeds, in which embryos develop without fertilization.” Or “Apomixis is a type of reproduction in which sexual organs of related structures take part but seeds are formed without union of gametes.” In some species of plants, an embryo develops from the diploid cells of the seed and not as a result of fertilization between ovule and pollen. This type of reproduction is known as apomixis and the seedlings produced in this manner are known as apomicts. Apomictic seedlings are identical to mother plant and similar to plants raised by other vegetative means, because such plants have the same genetic make-up as that of the mother plant. Such seedlings are completely free from viruses. In apomictic species, sexual reproduction is either suppressed or absent. When sexual reproduction also occurs, the apomixes is termed as facultative apomixis. But when sexual reproduction is absent, it is referred to as obligate apomixis. -

Systematic Significance of Pollen Morphology of Citrus (Rutaceae) from Owerri

Arom & at al ic in P l ic a n d Inyama et al., Med Aromat Plants 2015, 4:3 t e s M Medicinal & Aromatic Plants DOI: 10.4172/2167-0412.1000191 ISSN: 2167-0412 ResearchResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Systematic Significance of Pollen Morphology of Citrus (Rutaceae) from Owerri Inyama CN1*, Osuoha VUN2, Mbagwu FN1 and Duru CM3 1Department of Plant Science and Biotechnology, Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria 2Department of Biology, Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Owerri, Nigeria 3Department of Biotechnology, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria Abstract Palynological features of C. sinensis, C. limon, C. aurantifolia, C. paradisi, C. reticulata and C. maxima collected from various parts of Owerri were examined and evaluated in order to determine the taxonomic value of the observed internal peculiarities. Features related to pollen shape showed circular to elliptic shapes in all the taxa while rectangular shape distinguished C. limon, C. paradise and C. maxima. Polar view showed that C. paradisi and C. maxima have closer affinity than the other taxa studied. Palynological characters as observed in this study were found useful especially in delimiting the investigated taxa and thus could be exploited in conjunction with other evidences in specie identification and characterization. Keywords: Citrus; Pollen morphology; Systematic; Rutaceae Materials and Methods Introduction Specimen collection The use of palynological studies in solving taxonomic problems The studies were made on matured living materials of the six Citrus is gradually gaining grounds with vigorous extensive investigation species collected from Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources in the field of science. Diversified morphological details of pollen Nekede, Agricultural Development Programme (ADP) farms, Owerri. -

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 1

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Lecture 32 Citrus Citrus: Citrus spp., Rutaceae Citrus are subtropical, evergreen plants originating in southeast Asia and the Malay archipelago but the precise origins are obscure. There are about 1600 species in the subfamily Aurantioideae. The tribe Citreae has 13 genera, most of which are graft and cross compatible with the genus Citrus. There are some tropical species (pomelo). All Citrus combined are the most important fruit crop next to grape. 1 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 The common features are a superior ovary on a raised disc, transparent (pellucid) dots on leaves, and the presence of aromatic oils in leaves and fruits. Citrus has increased in importance in the United States with the development of frozen concentrate which is much superior to canned citrus juice. Per-capita consumption in the US is extremely high. Citrus mitis (calamondin), a miniature orange, is widely grown as an ornamental house pot plant. History Citrus is first mentioned in Chinese literature in 2200 BCE. First citrus in Europe seems to have been the citron, a fruit which has religious significance in Jewish festivals. Mentioned in 310 BCE by Theophrastus. Lemons and limes and sour orange may have been mutations of the citron. The Romans grew sour orange and lemons in 50–100 CE; the first mention of sweet orange in Europe was made in 1400. Columbus brought citrus on his second voyage in 1493 and the first plantation started in Haiti. In 1565 the first citrus was brought to the US in Saint Augustine. 2 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Taxonomy Citrus classification based on morphology of mature fruit (e.g. -

Cuban Tree Frog He's a Bad Boy!!

Dear Extension Friends, August 2014 We hope you are enjoying your summer by taking the proper precau- Inside this issue: tions to prevent sunburn and heat exhaustion. If you find yourself needing a Cuban Treefrog 1 break from the heat, you are welcome to visit Dr. Kyle Brown for gardening information and advice in the comfort of the air-conditioned office (1pm to Citrus Species and 2 5pm, Monday through Friday). Hybrids Best Regards, Join Us On Facebook! Bamboo Control 3 UF IFAS Extension Baker County Garden Spot Fruit Tree 4 Alicia R. Lamborn https://www.facebook.com/ Calendar: August Horticulture Extension Agent UFIFASBakerCountyGardenSpot Baker County Extension Service CUBAN TREE FROG HE’S A BAD BOY!! A Cuban Tree Frog has been found in Baker County recently. Please keep an eye out for this invasive pest as he eats native tree frogs and smaller lizards and snakes. Should you find one, bring to the Extension Office for positive identification. Make a Tree Frog Hangout from a 3 foot length of 1.25 inch diameter PVC pipe, stand upright in ground near house or shrubs. Check it often to see if you have this Bad Boy! For more information on the Cuban tree frog, see the following UF/ IFAS publications: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw259 http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw346 Photo Credits: Steven Johnson, University of Florida The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) is an Equal Opportunity Institution authorized to provide research, educational information, and other services only to individ- uals and institutions that function with non-discrimination with respect to race, creed, color, religion, age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, national origin, political opinions, or affiliations. -

Citrus Trifoliata (Rutaceae): Review of Biology and Distribution in the USA

Nesom, G.L. 2014. Citrus trifoliata (Rutaceae): Review of biology and distribution in the USA. Phytoneuron 2014-46: 1–14. Published 1 May 2014. ISSN 2153 733X CITRUS TRIFOLIATA (RUTACEAE): REVIEW OF BIOLOGY AND DISTRIBUTION IN THE USA GUY L. NESOM 2925 Hartwood Drive Fort Worth, Texas 76109 www.guynesom.com ABSTRACT Citrus trifoliata (aka Poncirus trifoliata , trifoliate orange) has become an aggressive colonizer in the southeastern USA, spreading from plantings as a horticultural novelty and use as a hedge. Its currently known naturalized distribution apparently has resulted from many independent introductions from widely dispersed plantings. Seed set is primarily apomictic and the plants are successful in a variety of habitats, in ruderal habits and disturbed communities as well as in intact natural communities from closed canopy bottomlands to open, upland woods. Trifoliate orange is native to southeastern China and Korea. It was introduced into the USA in the early 1800's but apparently was not widely planted until the late 1800's and early 1900's and was not documented as naturalizing until about 1910. Citrus trifoliata L. (trifoliate orange, hardy orange, Chinese bitter orange, mock orange, winter hardy bitter lemon, Japanese bitter lemon) is a deciduous shrub or small tree relatively common in the southeastern USA. The species is native to eastern Asia and has become naturalized in the USA in many habitats, including ruderal sites as well as intact natural commmunities. It has often been grown as a dense hedge and as a horticultural curiosity because of its green stems and stout green thorns (stipular spines), large, white, fragrant flowers, and often prolific production of persistent, golf-ball sized orange fruits that mature in September and October. -

Winter 2014-2015 (22:3) (PDF)

Contents NATIVE NOTES Page Fern workshop 1-2 Wavey-leaf basket Grass 3 Names Cacalia 4 Trip Report Sandstone Falls 5 Kate’s Mountain Clover* Trip Report Brush Creek Falls 6 Thank yous memorial 7 WEST VIRGINIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER News of WVNPS 8 VOLUME 22:3 WINTER 2014-15 Events, Dues Form 9 Judy Dumke-Editor: [email protected] Phone 740-894-6859 Magnoliales 10 e e e visit us at www.wvnps.org e e e . Fern Workshop University of Charleston Charleston WV January 17 2015, bad weather date January 24 2015 If you have thought about ferns, looked at them, puzzled over them or just want to know more about them join the WVNPS in Charleston for a workshop led by Mark Watson of the University of Charleston. The session will start at 10 A.M. with a scheduled end point by 12:30 P.M. A board meeting will follow. The sessions will be held in the Clay Tower Building (CTB) room 513, which is the botany lab. If you have any pressed specimens to share, or to ask about, be sure to bring them with as much information as you have on the location and habitat. Even photographs of ferns might be of interest for the session. If you have a hand lens that you favor bring it along as well. DIRECTIONS From the North: Travel I-77 South or 1-79 South into Charleston. Follow the signs to I-64 West. Take Oakwood Road Exit 58A and follow the signs to Route 61 South (MacCorkle Ave.). -

Chemical Constituents and Biological Activities of Zanthoxylum Limonella (Rutaceae): a Review

Supabphol & Tangjitjareonkun Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research December 2014; 13 (12): 2119-2130 ISSN: 1596-5996 (print); 1596-9827 (electronic) © Pharmacotherapy Group, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Benin City, 300001 Nigeria. All rights reserved. Available online at http://www.tjpr.org http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v13i12.25 Review Article Chemical Constituents and Biological Activities of Zanthoxylum limonella (Rutaceae): A Review Roongtawan Supabphol1 and Janpen Tangjitjareonkun2* 1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Srinakharinwirot University, Bangkok 10110, 2Department of Basic Science and Physical Education, Faculty of Science at Si Racha, Kasetsart University, Si Racha Campus, Chonburi 20230, Thailand *For correspondence: Email: [email protected] Received: 9 December 2013 Revised accepted: 20 October 2014 Abstract Zanthoxylum limonella belongs to the family of aromatic deciduous trees and shrubs, Rutaceae. In traditional medicine practice, various parts of Z. limonella are used for the treatment of dental caries, febrifugal, sudorific, rheumatism, diuretic, stomach ache and diarrhea. Secondary metabolites have been isolated the stems, stem barks, and fruits. The plant contains alkaloid, amide, lignin, coumarin and terpenoid compounds. The extracts of the various parts, essential oil from the fruits and some pure compounds of Z. limonella have been found to have biological activities, for example, mosquito repellent and mosquito larvicidal, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antitumour properties. -

A New Otter of Giant Size, Siamogale Melilutra Sp. Nov. \(Lutrinae

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title A new otter of giant size, Siamogale melilutra sp. nov. (Lutrinae: Mustelidae: Carnivora), from the latest Miocene Shuitangba site in north-eastern Yunnan, south-western China, and a total- evidence phylogeny of lutrines Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/11b1d0h9 Journal Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 16(1) ISSN 1477-2019 Authors Wang, X Grohé, C Su, DF et al. Publication Date 2018-01-02 DOI 10.1080/14772019.2016.1267666 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of Systematic Palaeontology ISSN: 1477-2019 (Print) 1478-0941 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjsp20 A new otter of giant size, Siamogale melilutra sp. nov. (Lutrinae: Mustelidae: Carnivora), from the latest Miocene Shuitangba site in north- eastern Yunnan, south-western China, and a total- evidence phylogeny of lutrines Xiaoming Wang, Camille Grohé, Denise F. Su, Stuart C. White, Xueping Ji, Jay Kelley, Nina G. Jablonski, Tao Deng, Youshan You & Xin Yang To cite this article: Xiaoming Wang, Camille Grohé, Denise F. Su, Stuart C. White, Xueping Ji, Jay Kelley, Nina G. Jablonski, Tao Deng, Youshan You & Xin Yang (2017): A new otter of giant size, Siamogale melilutra sp. nov. (Lutrinae: Mustelidae: Carnivora), from the latest Miocene Shuitangba site in north-eastern Yunnan, south-western China, and a total-evidence phylogeny of lutrines, Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2016.1267666 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2016.1267666 View supplementary material Published online: 22 Jan 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tjsp20 Download by: [UCLA Library] Date: 23 January 2017, At: 00:17 Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2016.1267666 A new otter of giant size, Siamogale melilutra sp. -

Supplementary Material for RUSSELL, DYRANA N., JAWWAD A

Supplementary Material for RUSSELL, DYRANA N., JAWWAD A. QURESHI, SUSAN E. HALBERT AND PHILIP A. STANSLY−Host Suitability of Citrus and Zanthoxylum Spp. for Leuronota fagarae and Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Psylloidea). Florida Entomologist 97(4) (December 2014) at http://purl.fcla.edu/fcla/entomologist/browse Corresponding author: Dr. J. A. Qureshi University of Florida/IFAS Southwest Florida Research and Education Center (SWFREC) 2685 SR 29N, Immokalee, Fl 34142, USA Phone: (239) 658-3400 Fax: (239) 658-3469 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Leuronota fagarae Burckhardt (Hemiptera: Psylloidea), an exotic psyllid described from South America, was first observed in 2001on a citrus relative Zanthoxylum fagara (L.) Sarg. (Sapindales: Rutaceae) in southern Florida. Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) is principal vector of the bacteria ‘Candidatus Liberibacter spp.’ causal agent of huanglongbing (HLB) or citrus greening disease. Both vector and disease are now well established in Florida and also reported throughout the Americas and Asia. The host range of D. citri is limited to citrus and some rutaceous relatives. Additional vectors and host plants could accelerate spread of HLB in citrus and threaten endangered species such as Zanthoxylum coriaceum A. Rich. and Zanthoxylum flavum Vahl. Experiments were conducted to evaluate adult survival, reproduction and nymphal development of psyllids on 3 Citrus and 4 Zanthoxylum species as well as orange jasmine, Murraya paniculata (Syn. M. exotica) (Sapindales: Rutaceae), a common ornamental and preferred host of D. citri. Leuronota fagarae in single male−female pairs at 24 °C lived an average 4-47 days, 4-12 fold longer on Zanthoxylum spp. (except Z. flavum) than on citrus. -

2019 Full Provisional List

Sheet1 All Plants Grafted. USDA inspected and Certified prior to Importing. Varieties Quantities Variety Description required Baboon Lemon A Brazilian lemon with very intense yellow rind and flesh. The flavour is acidic with almost a hint of lime. Tree is vigorous with large green leaves. Both tree and fruit are beautiful. Bearss Lemon 1952. Fruit closely resembles the Lisbon. Very juicy and has a high rind oil content. The leaves are a beautiful purple when first emerging, turning a nice dark green. Fruit is ready from June to December. Eureka Lemon Fruit is very juicy and highly acidic. The Eureka originated in Los Angeles, California and is one of their principal varieties. It is the "typical" lemon found in the grocery stores, nice yellow colour with typical lemon shape. Harvested November to May Harvey Lemon 1948.Having survived the disastrous deep freezes in Florida during the ’60’s and ’70’s. this varieties is known to withstand cold weather. Typical lemon shape and tart, juicy true lemon flavour. Fruit ripens in September to March. Self fertile. Zones 8A-10. Lisbon Lemon Fruit is very juicy and acic. The leaves are dense and tree is very vigorous. This Lisbon is more cold tolerant than the Eureka and is more productive. It is one of the major varieties in California. Fruit is harvested from February to May. Meyer Lemon 1908. Considered ever-bearing, the blooms are very aromatic. It is a lemon and orange hybrid. It is very cold hardy. Fruit is round with a thin rind. Fruit is juicy and has a very nice flavour, with a low acidity.