Arkell's Endings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Pages

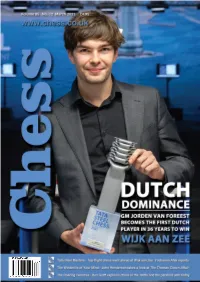

01-01 Cover -March 2021_Layout 1 17/02/2021 17:19 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/02/2021 09:47 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Jorden van Foreest.......................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with the man of the moment after Wijk aan Zee Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Dutch Dominance.................................................................................................8 The Tata Steel Masters went ahead. Yochanan Afek reports Subscription Rates: United Kingdom How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Daniel King presents one of the games of Wijk,Wojtaszek-Caruana 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 Up in the Air ........................................................................................................21 Europe There’s been drama aplenty in the Champions Chess Tour 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Howell’s Hastings Haul ...................................................................................24 3 year (36 issues) £165 David Howell ran -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

The Art of Staying Neutral the Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918

9 789053 568187 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 1 THE ART OF STAYING NEUTRAL abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 2 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 3 The Art of Staying Neutral The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 Maartje M. Abbenhuis abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 4 Cover illustration: Dutch Border Patrols, © Spaarnestad Fotoarchief Cover design: Mesika Design, Hilversum Layout: PROgrafici, Goes isbn-10 90 5356 818 2 isbn-13 978 90 5356 8187 nur 689 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 5 Table of Contents List of Tables, Maps and Illustrations / 9 Acknowledgements / 11 Preface by Piet de Rooij / 13 Introduction: The War Knocked on Our Door, It Did Not Step Inside: / 17 The Netherlands and the Great War Chapter 1: A Nation Too Small to Commit Great Stupidities: / 23 The Netherlands and Neutrality The Allure of Neutrality / 26 The Cornerstone of Northwest Europe / 30 Dutch Neutrality During the Great War / 35 Chapter 2: A Pack of Lions: The Dutch Armed Forces / 39 Strategies for Defending of the Indefensible / 39 Having to Do One’s Duty: Conscription / 41 Not True Reserves? Landweer and Landstorm Troops / 43 Few -

Dutch Arms Export Policy in 2018

Dutch Arms Export Policy in 2018 Report by the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation and the Minister of Foreign Affairs on the export of military goods July 2019 Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................... 3 2. Profile of the Dutch defence industry ....................................................... 4 3. Procedures and principles ....................................................................... 6 3.1 Procedures .............................................................................................................................. 6 3.2 Changes in 2018 ..................................................................................................................... 6 3.3 Principles ................................................................................................................................ 7 4. Transparency in Dutch arms export policy ................................................ 8 4.1 Trade in military goods ........................................................................................................... 8 4.2 Trade in dual-use goods ......................................................................................................... 9 4.3 Procedures .............................................................................................................................. 9 5. Dutch arms export in 2018 .................................................................... 11 6. Relevant developments -

Do First Mover Advantages Exist in Competitive Board Games: the Importance of Zugzwang

DO FIRST MOVER ADVANTAGES EXIST IN COMPETITIVE BOARD GAMES: THE IMPORTANCE OF ZUGZWANG Douglas L. Micklich Illinois State University [email protected] ABSTRACT to the other player(s) in the game (Zagal, et.al., 2006) Examples of such games are chess and Connect-Four. The players try to The ability to move first in competitive games is thought to be secure some sort of first-mover advantage in trying to attain the sole determinant on who wins the game. This study attempts some advantage of position from which a lethal attack can be to show other factors which contribute and have a non-linear mounted. The ability to move first in competitive board games effect on the game’s outcome. These factors, although shown to has thought to have resulted more often in a situation where that be not statistically significant, because of their non-linear player, the one moving first, being victorious. The person relationship have some positive correlations to helping moving first will normally try to take control from the outset and determine the winner of the game. force their opponent into making moves that they would not otherwise have made. This is a strategy which Allis refers to as “Zugzwang”, which is the principle of having to play a move INTRODUCTION one would rather not. To be able to ensure that victory through a gained advantage In Allis’s paper “A Knowledge-Based Approach of is attained, a position must first be determined. SunTzu in the Connect-Four: The Game is Solved: White Wins”, the author “Art of War” described position in this manner: “this position, a states that the player of the black pieces can follow strategic strategic position (hsing), is defined as ‘one that creates a rules by which they can at least draw the game provided that the situation where we can use ‘the individual whole to attack our player of the red pieces does not start in the middle column (the rival’s) one, and many to strike a few’ – that is, to win the (Allis, 1992). -

In This Issue

CHESS MOVES The newsletter of the English Chess Federation | 6 issues per year | May/June 2015 John Nunn, Keith Arkell and Mick Stokes at the 15th European Senior Chess Championships - John with his Silver Medal and Keith with his Bronze for the Over 50s section IN THIS ISSUE - ECF News 2-4 Calendar 14-16 Tournament Round-Up 5-6 Supplement --- Junior Chess 6-8 Simon Williams S7 Euro Seniors 9-10 Readers’ Letters S36 National Club 10 Never Mind the GMs S44 Grand Prix 11-12 Home News S52-53 Book Reviews 13 1 ECF NEWS The Chess Trust The Chess Trust has now been approved by the Charity Commission as registered charity no. 1160881. This will be the charitable arm of the ECF with wide ranging charitable purposes to support the provision and development of chess within England. This is good news There is still work to be done to enable the Trust to become operational, which the trustees will address over the next few months. The initial trustees are Ray Edwards, Keith Richardson, Julian Farrand, Phil Ehr and David Eustace. Questions about the Trust can be raised on the ECF Forum at http://www.englishchess.org.uk/Forum/view- topic.php?f=4&t=261 FIDE – ECF meeting report FIDE President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, ECF President Dominic Lawson and Russian Chess Federation President Andrei Filatov met in London on 11 March 2015. The other ECF participants were Chief Executive Phil Ehr and FIDE Delegate Malcolm Pein. The other FIDE participants were Assistant to the FIDE President Barik Balgabaev and Secretary of FIDE’s Chess in Schools Commission Sainbayar Tserendorj, who is also the founder and ECF Council member for the UK Chess Academy. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Electronic Funds Transfer Agreement and Disclosure VISA Checkmate and Electronic Services

Electronic Funds Transfer Agreement and Disclosure VISA CheckMate and Electronic Services This Electronic Fund Transfers Agreement and Disclosure is the contract which covers your and our rights and responsibilities concerning the electronic fund transfers (EFT) services offered to you by University of Virginia Community Credit Union (“Credit Union”). In this Agreement, the words “you,” “your,” and “yours” mean those who sign the application or account card as applicants, joint owners, or any authorized users. The words “we,” “us,” and “our” mean the Credit Union. The word “account” means any one (1) or more share and checking accounts you have with the Credit Union. Electronic fund transfers are electronically initiated transfers of money from your account through the EFT services described below. By signing an application or account card for EFT services, signing your card, or using any service, each of you, jointly and severally, agree to the terms and conditions in this Agreement and any amendments for the EFT services offered. Furthermore, electronic fund transfers that meet the definition of remittance transfers are governed by 12 C.F.R. part 1005, subpart B—Requirements for remittance transfers, and consequently, terms of this agreement may vary for those types of transactions. A “remittance transfer” is an electronic transfer of funds of more than $15.00 which is requested by a sender and sent to a designated recipient in a foreign country by a remittance transfer provider. Terms applicable to such transactions may vary from those disclosed herein and will be disclosed to you at the time such services are requested and rendered in accordance with applicable law. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3

01-01 Cover - October 2020_Layout 1 18/09/2020 14:00 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Peter Wells.......................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine The acclaimed author, coach and GM still very much likes to play Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Online Drama .........................................................................................................8 Danny Gormally presents some highlights of the vast Online Olympiad Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Carlsen Prevails - Just ....................................................................................14 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Nakamura pushed Magnus all the way in the final of his own Tour 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Find the Winning Moves.................................................................................18 3 year (36 issues) £125 Can you do as well as the acclaimed field in the Legends of Chess? Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Opening Surprises ............................................................................................22 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 -

Owen Mccoy on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess US Chess Master Owen Mccoy

orthwes $3.95 N t C h May 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Washington, and Idaho Owen McCoy On the front cover: Northwest Chess US Chess Master Owen McCoy. (See story pp. 4-7.) May 2018, Volume 72-05 Issue 844 Photo credit: Sarah McCoy. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: GM Julio Sadorra doing a pushup at Kerry Park on Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Queen Anne overlooking downtown Seattle. (Don’t try Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. this at home, kids!) Photo credit: Jacob Mayer. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, NWC Staff of West Linn, Oregon. Editor: Jeffrey Roland, [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Submissions Publisher: Duane Polich, [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. All rights reserved. -

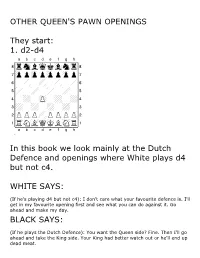

OTHER QUEEN's PAWN OPENINGS They Start: 1. D2-D4 XABCDEFGH

OTHER QUEEN'S PAWN OPENINGS They start: 1. d2-d4 XABCDEFGH 8rsnlwqkvlntr( 7zppzppzppzpp' 6-+-+-+-+& 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-zP-+-+$ 3+-+-+-+-# 2PzPP+PzPPzP" 1tRNvLQmKLsNR! Xabcdefgh In this book we look mainly at the Dutch Defence and openings where White plays d4 but not c4. WHITE SAYS: (If he's playing d4 but not c4): I don't care what your favourite defence is. I'll get in my favourite opening first and see what you can do against it. Go ahead and make my day. BLACK SAYS: (If he plays the Dutch Defence): You want the Queen side? Fine. Then I'll go ahead and take the King side. Your King had better watch out or he'll end up dead meat. XABCDEFGHY 8rsnlwq-trk+( 7zppzp-vl-zpp' The Classical Dutch. 6-+-zppsn-+& Black's plans are to play e6-e5 or to 5+-+-+p+-% attack on the King side with moves like 4-+-+-+-+$ Qd8-e8, Qe8-h5, g7-g5, g5-g4. White 3+-+-+-+-# will try to play e2-e4, open the e-file 2-+-+-+-+" and attack Black's weak e-pawn. For this reason he will usually develop his 1+-+-+-+-! King's Bishop on g2. xabcdefghy xABCDEFGH 8rsnlwq-trk+( 7zpp+-+-zpp' The Dutch Stonewall. 6-+pvlpsn-+& Black gains space but leaves a 5+-+p+p+-% weakness on e5. He can either play for 4-+-+-+-+$ a King side attack, again with Qd8-e8, 3+-+-+-+-# Qe8-h5, g7-g5, or play in the centre 2-+-+-+-+" with b7-b6 and c6-c5. White will aim to control or occupy the e5 square with a 1+-+-+-+-! Knight while trying to break with e2-e4.