Macron and the Gilets Jaunes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Populism in Europe

2018 State of Populism in Europe The past few years have seen a surge in the public support of populist, Eurosceptical and radical parties throughout almost the entire European Union. In several countries, their popularity matches or even exceeds the level of public support of the centre-left. Even though the centre-left parties, think tanks and researchers are aware of this challenge, there is still more OF POPULISM IN EUROPE – 2018 STATE that could be done in this fi eld. There is occasional research on individual populist parties in some countries, but there is no regular overview – updated every year – how the popularity of populist parties changes in the EU Member States, where new parties appear and old ones disappear. That is the reason why FEPS and Policy Solutions have launched this series of yearbooks, entitled “State of Populism in Europe”. *** FEPS is the fi rst progressive political foundation established at the European level. Created in 2007 and co-fi nanced by the European Parliament, it aims at establishing an intellectual crossroad between social democracy and the European project. Policy Solutions is a progressive political research institute based in Budapest. Among the pre-eminent areas of its research are the investigation of how the quality of democracy evolves, the analysis of factors driving populism, and election research. Contributors : Tamás BOROS, Maria FREITAS, Gergely LAKI, Ernst STETTER STATE OF POPULISM Tamás BOROS IN EUROPE Maria FREITAS • This book is edited by FEPS with the fi nancial support of the European -

2020 France Country Report | SGI Sustainable Governance Indicators

France Report Yves Mény, Henrik Uterwedde, Reimut Zohlnhöfer (Coordinator) Sustainable Governance Indicators 2020 © vege - stock.adobe.com Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2020 | 2 France Report Executive Summary France enjoys solid institutions of governance, and under the Fifth Republic has benefited from the most stable, consensual and efficient period of the past 200 years. Yet the country has struggled to effectively address the challenges associated with Europeanization and globalization. The helplessness of the previous conservative and socialist governments faced with the deep economic crisis has contributed to the rise of radical populist parties on the left (La France Insoumise) and the right (National Rally), and a deep distrust between large segments of the population and the political class. The 2017 presidential election failed to remedy this situation, as the upsurge of the Yellow Vest movement (Gilets jaunes) showed particularly between November 2018 and June 2019. The social tensions are still acute and ready to unfold. Politically, aside from the unexpected landslide victory of a candidate who had no party support, one of the most striking consequences of the 2017 election has been the dramatic fragmentation of the traditional parties of government. The Socialist party of former President François Hollande is in pieces, lacking either a viable program or viable leadership. In October 2018, the left wing seceded, and the leaders of each the various factions have either been defeated or have retired. After the collapse of their candidate in the presidential election, the Conservatives (Les Républicains) chose a young new leader (Laurent Wauquiez) who was later forced to resign in June 2019 after the failure of his strategy at the European elections. -

EUI RSCAS Working Paper 2021Safety of Journalists in Europe

RSC 2021/43 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom Safety of journalists in Europe: Threats and best practices to tackle them Edited by Mária Žuffová and Roberta Carlini European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom Safety of journalists in Europe: Threats and best practices to tackle them Edited by Mária Žuffová and Roberta Carlini EUI Working Paper RSC 2021/43 Terms of access and reuse for this work are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC- BY 4.0) International license. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper series and number, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Edited by Mária Žuffová and Roberta Carlini, 2021 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0) International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Published in Μarch 2021 by the European University Institute. Badia Fiesolana, via dei Roccettini 9 I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual author(s) and not those of the European University Institute. This publication is available in Open Access in Cadmus, the EUI Research Repository: https://cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. -

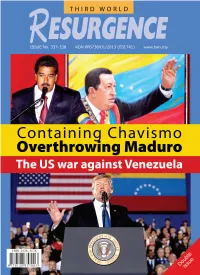

Editor's Note

Editor’s Note VENEZUELA is currently being crucified by a US- to the extent of consulting his advisers on how he could led coalition of states simply because it has chosen to trigger a war with Venezuela to seize the oilfields as embark on an alternative path of development. Such a war booty. brutal response by the US to any nation state opting Given this obsession, Trump’s first concern was for a different model of development is not in itself to ensure that the man at the helm in Venezuela was a anything new. Cuba has been the victim of US sanctions pliable person who would dutifully see to it that US since 1959 when Fidel Castro emerged victorious in interests were protected. Since Maduro did not fit the the guerilla war which toppled the corrupt US-backed bill, the only way out was regime change. In a brazen regime of Fulgencio Batista. Originally limited to the display of imperial power, Trump even effectively purchase of arms, the restrictions were subsequently nominated the candidate whom the Venezuelan people expanded to make it a more comprehensive sanctions were supposed to elect if they wanted the US to lift regime. sanctions. When Hugo Chavez became the President of The US’ man was Juan Guaido, who had been Venezuela in 1999 and proclaimed the Bolivarian groomed by an elite US-funded regime change training Revolution (a socialist political programme named after academy. Known by its acronym CANVAS, the the South American independence hero Simon Bolivar), organisation has, according to award-winning journalist the US was anything but pleased. -

Section Tests Tests

Section Tests Tests In this section, the reader will find 600 questions mostly based on the contents of the book and testing the whole spectrum of cultural references in the French press. For the general reader, these tests can be seen as an entertaining way to check on their general knowledge about France and the French language. For the student working alone, these tests can be a useful tool for self-assessment. For the teacher, these tests can be useful in several ways. They can be used as ‘entry’ or upstream ‘diagnostic’ tests for students starting a new course, or as tests for continued assessment. They may also be used as exit tests at the end of a given course, the teacher being free to fix what he or she considers to be a ‘pass’ mark in the light of previous students’ results. Test 1: Popular cultural references 1) Which of the following is not an expression associated with French childhood? a) Jeu de main, jeu de vilain b) C’est celui qui dit, qui l’est c) La souris verte d) Droit dans mes bottes 2) Which of the following is not a song by Serge Gainsbourg? a) Sea, sex and sun b) Je t’aime moi non plus c) Le Poinçonneur des Lilas d) Foule sentimentale 3) Which of the following is not the title of a famous film? a) La Grande Vadrouille b) La Bonne du curé c) Elle court, elle court la banlieue d) Le Bonheur est dans le pré Information Classification: General 4) Which of the following is not associated with Sartre and de Beauvoir? a) La Coupole b) Les Deux Magots c) Le Café de Flore d) Le Pavillon Gabriel 5) Which of the following is not a French cinema classic? a) Quai des brumes b) Hôtel du Nord c) La Guerre des Boutons d) Le Passager de la pluie 6) Find the odd man out among the following slang words. -

Qatar Vows to Continue with Support to Palestinians

BUSINESS | 13 SPORT | 16 GWC records 10% Qatar’s Haroun storms growth in H1 net to 400m win in London profits with record run Sunday 22 July 2018 | 9 Dhul-Qa’da I 1439 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 23 | Number 7595 | 2 Riyals Qatar ranks high in Global Entrepreneurship Index Amir to Visit Qatar vows to continue with UK today 22nd 55% 137 14 QNA support to Palestinians Rank Qatar Score of Countries Areas secured in Qatar ranked in covered DOHA: Amir H H Sheikh the index in the index the study in GEI Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani THE PENINSULA “The State of the eternal capital of the Israeli will visit the United Kingdom Qatar, under the entity, transferring embassies to today, at the invitation of DOHA: Advisory Council leadership of H H remove the issue of Jerusalem Prime Minister Theresa May. Speaker H E Ahmed bin Zaid Al from any negotiations and sub- H H the Amir and the Mahmoud has stressed that the the Amir, has been sequent agreements to an unjust Prime Minister will hold talks State of Qatar, under the lead- and will continue to siege on the Gaza Strip, an on Tuesday to discuss the ership of Amir H H Sheikh support the people attempt to end and bring down strengthening of the friendly Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, has in Gaza Strip and the refugee issue and the right relations and cooperation been and will continue to to return and the Israeli par- between the two countries in support the people in Gaza Strip the West Bank with liament adoption of the “nation- various fields, in addition to and the West Bank with deter- determination and state law” that perpetuates dis- a number of regional and mination and sincerity in all sincerity in all their crimination and abhorrent international issues of their conditions. -

By JUAN BRANCO

CREPUSCULE By JUAN BRANCO 1 Foreword, by DENIS ROBERT1 It was early November 2018 when the French President completed his remembrance tour with a visit to Pont-à-Mousson, on the Moselle river. He was to close a conference, using English loanwords to “make up” the future world as he saw it: Choose France Grand Est. I have a friend there who is a doctor. I suspect he might have voted for Emmanuel Macron in both rounds of the presidential election. Let’s be perfectly honest, I did the same in the second round, without any qualms whatsoever. This friend of mine, who I suspect always votes for the right wing, sent me a long e-mail message a few days later with ten or so instructive photographs attached. It was as though a lethal gas had wiped out an entire town. Not a single inhabitant of Pont-à-Mousson was in the streets. Place Duroc was completely shut off to the population. The same was true for Prémontrés abbey where the five hundred conference attendees, elected officials and leaders, hand-picked, searched and wearing ties, were penned in. That afternoon, it was as if the town was anaesthetized. The people had been sidelined. There was not a soul around, no free citizen in a radius of approximately 500 meters around Emmanuel Macron. Nothing but metal barriers, rural police forces and anti-riot police waiting in dozens of coaches parked along the river banks. Television that evening, and newspapers the day after, noted the success of the presidential visit, but failed to report the sidelining of the unwelcome common people. -

State-Backed Information Manipulation: the French Node

State-backed Information Manipulation: The French Node POLICY PAPER FEBRUARY 2021 Institut Montaigne is a nonprofit, independent think tank based in Paris, France. Our mission is to craft public policy proposals aimed at shaping political debates and decision making in France and Europe. We bring together leaders from a diverse range of backgrounds - government, civil society, corporations and academia - to produce balanced analyses, international benchmarking and evidence-based research. We promote a balanced vision State-backed Information of society, in which open and competitive markets go hand in hand with equality of opportunity and social cohesion. Our strong commitment to representative democracy and citizen participation, on the one hand, and European sovereignty and integration, Manipulation: The French on the other, form the intellectual basis for our work. Institut Montaigne is funded by corporations and individuals, none of whom contribute to more than 3% of its annual budget. Node POLICY PAPER – FEBRUARY 2021 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexandra Pavliuc, visiting fellow on information manipulation networks at Institut Montaigne and doctoral student at the Oxford Internet Institute. Alexandra is a DPhil student in Social Data Science at the Oxford Internet Institute and a researcher on the Computational Propaganda Project. Alexandra’s research explores how network analysis can highlight structures and strategies of manipulative communication across social media platforms. Her research in this field has been published by the NATO Defence Strategic Communications Journal and The Wilson Center. Alexandra holds an MSc in Data Science at City, University of London and a BA in Professional Communication with a Minor in Physics from Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada. -

Top French Presidential Aide Held for Illegally Assaulting

افغانستان آزاد – آزاد افغانستان AA-AA چو کشور نباشـد تن من مبـــــــاد بدین بوم و بر زنده یک تن مــــباد همه سر به سر تن به کشتن دهیم از آن به که کشور به دشمن دهیم www.afgazad.com [email protected] زبانهای اروپائی European Languages 21 July 2018 By Anthony Torres 23.07.2018 Top French presidential aide held for illegally assaulting peaceful protesters Alexandre Benalla, a close aide of President Emmanuel Macron and his deputy chief of staff, has been detained for questioning by police after it emerged that he illegally donned a CRS riot police helmet and its insignia, and then assaulted two peaceful protesters on May Day. For several months the Elysée presidential palace covered up this brutal and illegal attack on protesters exercising their democratic rights. The scandal involving the man charged with security for Macron’s presidential campaign erupted on Wednesday evening, when Le Monde posted an article reporting: “Alexandre Benalla, a close adviser of the President … wearing a helmet of the police forces though he is not a policeman, attacked a youth lying on the ground during a demonstration taking place on the Place de la Contrescarpe in Paris. The helmeted man loses control, drags the youth on the ground, violently grabs him by the neck then strikes him several times.” In a video published by Le Monde, a group of CRS first drags the youth along the ground. Benalla, wearing a CRS helmet and armband, then returns and again forces the youth to the ground, grabs his neck and strikes him repeatedly on the head and body. -

9729 Sommaire Analytique Commission Des Affaires

9729 SOMMAIRE ANALYTIQUE COMMISSION DES AFFAIRES SOCIALES ................................................................ 9733 Projet de loi constitutionnelle pour une démocratie plus représentative, responsable et efficace – Audition de M. Benjamin Ferras, haut fonctionnaire au sein des ministères sociaux, maître de conférences à Sciences Po Paris .................................................................... 9733 Projet de loi pour la liberté de choisir son avenir professionnel – Examen, en nouvelle lecture, du rapport et du texte de la commission ......................................................................... 9744 Nomination de rapporteurs .......................................................................................................... 9754 COMMISSION DE LA CULTURE, DE L'ÉDUCATION ET DE LA COMMUNICATION ......................................................................................................... 9755 Proposition de loi relative à la lutte contre la manipulation de l'information - Examen des amendements de séance ............................................................................................................... 9755 Mission d’information sur le métier d’enseignant - Présentation du rapport d’information ...... 9755 Mission d’information sur le mécénat - Présentation du rapport d’information ......................... 9763 COMMISSION DES FINANCES ..................................................................................... 9771 Projet de loi ratifiant l’ordonnance n° 2017-1252 -

Aug. 2, 2018, Vol. 60, No. 31

Trump, Putin y Helsinki 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 60, No. 31 August 2, 2018 $1 Anthem policy on hold NFL players push back bosses By Monica Moorehead dented one. In January 1934, the fascist take place. A July 19 public joint state- defensive end for the Tennessee Titans, Nazi government banned its football club ment read: “No new rules relating to the stated that he will continue to protest July 30 — The struggle between Na- from playing against a French team when anthem will be issued or enforced for the during the anthem, policy or no policy. tional Football League players and bil- the club refused to give the Nazi salute next several weeks while these confiden- Casey told CNN: “I’m going to take a lionaire owners continues to dominate before a game. tial discussions are ongoing.” (CNN.com) fine this year. Why not? I’m going to pro- sports and political headlines on social A July 10 press release from the NFL- If the bosses’ decision eventually gets test during the flag.” (July 18) issues. The NFL Players Association, PA stated: “Our union filed its non-injury enforced, it would give the NFL hierar- Where pro football is concerned, the union representing the players in a grievance today on behalf of all players chy the right to fine any player for taking standing for the U.S. national anthem league that is at least 70 percent Black, challenging the NFL’s recently imposed a knee or expressing any kind of protest first began in 2009. -

France Report Yves Mény, Henrik Uterwedde, Reimut Zohlnhöfer (Coordinator)

France Report Yves Mény, Henrik Uterwedde, Reimut Zohlnhöfer (Coordinator) Sustainable Governance Indicators 2019 © vege - stock.adobe.com Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2019 | 2 France Report Executive Summary France enjoys solid institutions of governance, and is enjoying its most stable, consensual and efficient period over the past 200 years. Yet, the country has struggled to effectively address the challenges associated with Europeanization and globalization. The helplessness of the previous conservative and socialist governments faced with the deep economic crisis has contributed to the rise of radical populist parties on the left (Mélenchon) and the right (National Front), and a deep distrust between large segments of the population and the political class. In the wake of President Trump’s election in the United States and of the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, there were fears that right-populist Marine Le Pen might be the winner of a polarized presidential election in France, which has raised serious doubts about the country’s capacity for systemic reforms. The presidential election and the victory of Macron over Le Pen has opened a completely new horizon both in political and policy terms. Politically, aside from the unexpected landslide victory of a candidate who had no party support, the striking consequence is the dramatic fragmentation of the traditional parties of government. The Socialist party of former president Hollande is in pieces, has no program and no real leadership. It is not even guaranteed 5% of the vote in the forthcoming European elections, according to recent opinion polls. In October 2018, the left wing seceded and all the leaders of the various factions have been defeated or have retired.