The Following PDF Documents Total 271 Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

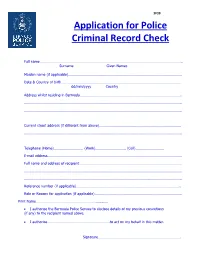

Application for Police Criminal Record Check

SF39 Application for Police Criminal Record Check Full name……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Surname Given Names Maiden name (if applicable)…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Date & Country of birth…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… dd/mm/yyyy Country Address whilst residing in Bermuda………………………………………………………………………………………….. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Current street address (if different from above)………………………………………………………………………… …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Telephone (Home)………………………… (Work)…………………………. (Cell)……………………….. E-mail address……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Full name and address of recipient…………………………………………………………………………………………… …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Reference number (if applicable)…………………………………………………………………………………………….. Role or Reason for application (if applicable)…………………………………………………………………………….. Print Name……………………………………………………............ I authorize the Bermuda Police Service to disclose details of my previous convictions (if any) to the recipient named above. I authorize……………………………………………………….to act on my behalf in this matter. Signature…………………………………………………………………………. Instructions for Submitting Requests & Documentation IMPORTANT The Bermuda Police Service will only accept applications for Police Record Checks under the following circumstances: 1. Local applicants: A fee of $100 should be submitted -

Criminal Background Check Procedures

Shaping the future of international education New Edition Criminal Background Check Procedures CIS in collaboration with other agencies has formed an International Task Force on Child Protection chaired by CIS Executive Director, Jane Larsson, in order to apply our collective resources, expertise, and partnerships to help international school communities address child protection challenges. Member Organisations of the Task Force: • Council of International Schools • Council of British International Schools • Academy of International School Heads • U.S. Department of State, Office of Overseas Schools • Association for the Advancement of International Education • International Schools Services • ECIS CIS is the leader in requiring police background check documentation for Educator and Leadership Candidates as part of the overall effort to ensure effective screening. Please obtain a current police background check from your current country of employment/residence as well as appropriate documentation from any previous country/countries in which you have worked. It is ultimately a school’s responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate police background documentation for their Educators and CIS is committed to supporting them in this endeavour. It is important to demonstrate a willingness and effort to meet the requirement and obtain all of the paperwork that is realistically possible. This document is the result of extensive research into governmental, law enforcement and embassy websites. We have tried to ensure where possible that the information has been obtained from official channels and to provide links to these sources. CIS requests your help in maintaining an accurate and useful resource; if you find any information to be incorrect or out of date, please contact us at: [email protected]. -

Standard & Poor's Review of HSBC Bank Bermuda

Research Update: HSBC Bank Bermuda Ltd. Outlook Revised To Stable From Negative On Encouraging Indicators; Ratings Affirmed Primary Credit Analyst: Nikola G Swann, CFA, FRM, Toronto (1) 416-507-2582; [email protected] Secondary Contact: E.Robert Hansen, CFA, New York (1) 212-438-7402; [email protected] Table Of Contents Overview Rating Action Rationale Outlook Related Criteria Ratings List WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT FEBRUARY 19, 2019 1 Research Update: HSBC Bank Bermuda Ltd. Outlook Revised To Stable From Negative On Encouraging Indicators; Ratings Affirmed Overview • We continue to see encouraging recent economic indicators in Bermuda, the principal jurisdiction of operations for HSBC Bank Bermuda (HBBM), one of two banks that control the vast majority of the local market. • A strategy update by the bank's parent (HSBC Holdings PLC) appears to have concluded without meaningfully reducing HBBM's strategic importance to the group, lowering the likelihood of this downside risk. • We believe the likelihood that future capital payouts to the parent are as high a share of annual net income as the amounts paid in 2016 and certain previous years is also lower. • In light of this, we now view the probability of upside and downside movement in the ratings as approximately balanced. • Therefore, we are revising our outlook on HBBM to stable from negative and affirming our 'A-/A-2' issuer credit ratings on the bank. Rating Action On Feb. 19, 2019, S&P Global Ratings revised its outlook on HSBC Bank Bermuda (HBBM) to stable from negative. At the same time, S&P Global Ratings affirmed its 'A-/A-2' issuer credit ratings on the bank. -

HSBC BERMUDA – 13Th YEAR AS PROUD LEAD SPONSOR for the CUP MATCH CLASSIC

News Release July 9th, 2019 HSBC BERMUDA – 13th YEAR AS PROUD LEAD SPONSOR FOR THE CUP MATCH CLASSIC As host of the 2019 Cup Match Classic, St. George’s Cricket Club’s President Neil Paynter, today announced the return of HSBC Bermuda (‘HSBC’) as lead sponsor. Steve Banner, HSBC Bermuda CEO said, “This will be HSBC’s 13th consecutive year as the lead sponsor of this exciting competition. At HSBC we are delighted to be able to once again support the respective efforts of the St. George’s and Somerset Cricket Clubs, and we all look forward to a wonderful community event.” St. George’s Cricket Club’s President Neil Paynter shared: “We have had a long and successful history with HSBC and Cup Match. The Club are particularly grateful for all that the bank’s sponsorship enables us to be able to provide to the local community. -ends more- This news release is issued by Registered Office: 37 Front Street, Hamilton HM11, Bermuda. HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited “It is a fantastic event and on behalf of the Club I extend my sincere thanks to HSBC for once again sponsoring us as we strive to bring the Cup back ‘home’ to St. George’s.” Head of Retail Banking Wealth Management – Renee Bullock-Cann and St. George’s Club President – Neil Paynter Head of Retail Banking Wealth Management – Renee Bullock-Cann had this to say: “In the lead up to the two day event our employees will be busy with a number of community focused, Cup Match related activities. There will also be a number of them on hand during the two day event at the grounds of the St. -

HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited Financial Statements 2020 1 Independent Auditor's Report

;+;+ 2020 HSBC BANK BERMUDA LIMITED Consolidated Financial Statements Contents Page Independent auditor’s report 2 Consolidated financial statements 4 Consolidated income statement 4 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 4 Consolidated balance sheet 5 Consolidated statement of cash flows 6 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 7 Notes on the consolidated financial statements 8 1 Basis of preparation 8 2 Significant accounting policies 9 3 Net interest income and net fee income 17 4 Employee compensation and benefits 17 5 Share-based payments 19 6 Tax expense 20 7 Derivatives 20 8 Loans and advances to banks 21 9 Credit risk 23 10 Loans and advances to customers 26 11 Financial investments 28 12 Fair values of financial investments carried at fair value 30 13 Property and equipment 31 14 Group entities 31 15 Provisions 32 16 Contingent liabilities, contractual commitments and guarantees 32 17 Maturity analysis of financial assets and financial liabilities 33 18 Interest rate analysis of financial instruments 35 19 Foreign currency exposures 36 20 Risk management 36 21 Litigation 46 22 Related party transactions 47 23 Equity 48 HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited Financial Statements 2020 1 Independent auditor's report To the Board of Directors and Shareholder of HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited Our opinion In our opinion, the consolidated financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the consolidated financial position of HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited (the Company) and its subsidiaries (together ‘the Group’) as at 31 December 2020, and their consolidated financial performance and their consolidated cash flows for the year then ended in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards. -

Getting to Know You Your Account Opening Journey

Getting to Know You Your Account Opening Journey What will happen during your Account Opening appointment? Which account Getting to Opening of Advice on is best for you ? know you Account Next Steps What to Bring to your Appointment: Your HSBC Debit Card Each applicant will need to bring one form of identification 4 Your Debit Card will be ready for collection from the and proof of address, as well as an initial deposit of branch of your choice 7 business days following BMD$100 (or equivalent currency) to open an account. your Account Opening Appointment. 4 Please bring valid ID to collect your Debit Card Identification (ID) Bermudian Non-Bermudian* Personal Internet Banking & your ► Passport 4 Passport HSBC Security Device ► Bermuda Driver’s Licence Once you have your Debit Card, you will be able to set up ► Bermuda Voter’s your Personal Internet Banking. Registration Card 4 To register, visit www.hsbc.bm and click on Personal ► Special Person’s Card Internet Banking at the bottom of our homepage. *If Non -Bermudian , please also bring your tie to Bermuda 4 You will be provided with your HSBC Security Device (i.e. Work Permit, Spouse Letter, Permanent Resident when you collect your Debit Card. The HSBC document). Security Device allows you to transfer funds securely and offers enhanced fraud protection for your To avoid disappointment, please ensure that your ID is account. For detailed instructions, visit www.hsbc.bm current and includes your full name. and follow the Online Security link at the bottom of the page. Verification of Address Fixed Residence Temporary Residence HSBC Mobile Banking App ► Driver’s Licence ► Work Permit ► Lease Agreement ► Employment Letter 4 Download the HSBC Mobile Banking App to your smartphone (visit the App store or ► Utility bill (i.e. -

DONOR FUND CONTRIBUTION THIRD PARTY PAYMENT INSTRUCTIONS Banking and Payment Information Wire Transfer Correspondent Bank

DONOR FUND CONTRIBUTION THIRD PARTY PAYMENT INSTRUCTIONS Banking and Payment Information Wire Transfer Correspondent Bank: HSBC Bank USA, N.A. 452 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10018, U.S.A. SWIFT Codes (non-US banks): MRMD US33 Fedwire ABA Code (US banks) 021001088 The above code identifies HSBC New York, however, only one is needed. The choice of code is dependent on the payment system used by the remitting bank. Beneficiary Account Name: Friends of Bermuda Community Foundation Beneficiary Bank Name: HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited, Hamilton SWIFT Codes (non-US banks): BBDA BMHM Bermuda Bank Address: 37 Front Street, Hamilton HM 11, Bermuda Beneficiary Name: Friends of Bermuda Community Foundation Beneficiary Account Number: Account # 011-131570-501 CUI USD Beneficiary Address: c/o Sterling House, 16 Wesley Street, 4th Floor, Hamilton HM 11, Bermuda Bank Contact Phone Number: 1 441 299 5555 Local Transfers (HSBC) - For other banks, please follow your bank’s process - Go to: Transfers Make a transfer Input the personal account number/ fund code provided by FBCF (a 4-6 alpha code) For the last four-digits of the “beneficiary’s account”, enter “0000” Note to beneficiary and account: First Initial, Last Name or Fund Reference provided by FBCF Online Banking: Direct payment through HSBC – AVAILABLE SOON. Go to: Pay bills Add Friends of Bermuda Community Foundation as a payee Pay multiple bills (BMD only) Proceed with the transaction Note to beneficiary and account: First Initial, Last Name or Fund Reference provided by FBCF ***Payment reference # _______________________ Date of Payment: _________________M/D/Y Return form to: Friends of BCF c/o Bermuda Community Foundation, Sterling House, 16 Wesley Street, 4th Floor, Hamilton HM 11, Bermuda, [email protected] (scan) or (441) 295-4897 (fax). -

Mastercard® Summary of Benefits for Consumer Credit Cards

Mastercard® Summary of Benefits for Consumer Credit Cards Benefits provided by Mastercard®. This general guide is for informational purposes and applies to HSBC Mastercard® cardholders only. www.hsbc.bm/cards ©HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited. September 2020 Issued by HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited, of 37 Front Street, Hamilton Bermuda, which is licensed to conduct Banking and Investment Business by the Bermuda Monetary Authority. Mastercard® Summary of Benefits for Consumer Credit Cards HSBC Mastercard® HSBC BermudaCard HSBC Advance HSBC Premier HSBC Premier (Standard) Mastercard® (Gold) Mastercard® (Platinum) Mastercard® Black Credit Cards Description of Benefits Mastercard Global Service provides emergency card- related assistance, anytime, anywhere, Mandated Mandated Mandated Mandated via one toll-free phone call. Conceirge Service provides N/A N/A Yes Yes personal assistance 24/7/365 to fulfill every cardholder request resourcefully, efficiently and, often, with a little touch of magic. We provide global and local service, allowing us to offer all types of assistance tailored to each cardholder’s specific needs, with restaurant reservations, special experiences arrangements, entertainment information and booking, and referrals among others. Mastercard Airport Experience N/A N/A N/A Yes provided by LoungeKey, offers cardholders the opportunity to relax, refresh and escape the common airport headaches as they wait for their flight. Boingo Wi-Fi for Mastercard N/A N/A Cardholders are provided Cardholders are provided Cardholders provides global free and unlimited access free and unlimited access access to over 1 million hotspots on up to four devices on up to four devices with connections 4x faster than global after registering for after registering for average broadband speed. -

Standard & Poor's Review of HSBC Bank Bermuda

HSBC Bank Bermuda Ltd. Primary Credit Analyst: Lidia Parfeniuk, Toronto + 1 (416) 507 2517; [email protected] Secondary Contact: Shameer M Bandeally, Toronto + 1 (416) 507 3230; [email protected] Table Of Contents Credit Highlights Outlook Anchor: 'bbb-' For A Bank Operating In Bermuda Business Position: Significant Market Share Position In Bermuda Capital And Earnings: Very Strong RAC Ratio, But The Bank Pays Large Dividends To The Parent Risk Position: NPAs Are Significantly Higher Than Peers' Though Loan Losses Could Rise Only Modestly Funding And Liquidity: Funding Is Average For A Bermudian Bank And Liquidity Is Strong Support: Three Notches Of Uplift Given Our View Of HBBM's Strategic Importance To Its Parent Key Statistics Related Criteria WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JULY 28, 2021 1 HSBC Bank Bermuda Ltd. Additional SACP bbb- Support +3 0 + + Factors Anchor bbb- Issuer Credit Rating ALAC 0 Business Support Adequate Position 0 Capital and GRE Support Very Strong 0 Earnings +2 Risk Position Weak -2 Group A-/Stable/A-2 Support +3 Funding Average 0 Sovereign Liquidity Strong Support 0 Credit Highlights Overview Key strengths Key risks Strategically important subsidiary of HSBC Holdings PLC Elevated nonperforming assets (NPAs) versus those of peers Leading competitive position in Bermuda Geographically concentrated loan portfolio, with large single-name exposures Very strong S&P Global Ratings risk-adjusted capital (RAC) ratio Large capital returns to shareholders on several occasions in the past decade Large proportion of high-quality liquid assets Very strong S&P Global Ratings RAC ratio would be somewhat pressured should there be a special dividend to the parent and the expectation of higher risk-weighted assets (RWA) growth. -

HSBC Corporate Money Funds Limited - Canadian Dollar Fund

BM-BE HSBC Corporate Money Funds Limited - Canadian Dollar Fund Share Class R 31 Aug 2021 R BMG4641E1416 31/08/2021 Fund Objective and Strategy HSBC Corporate Money Fund aims to provide a high level of current income consistent with the preservation of capital and the maintenance of liquidity by investing in a diversified portfolio of money market instruments. Instrument Mix % Maturity Ladder % Credit Quality Mix % Share Class Details UCITS V Compliant No Distribution Type Accumulating Dealing Frequency Daily Valuation Time 13:30 Bermuda Dealing Cut Off Time 11:00 Bermuda Min. Initial Investment CAD 10,000 Bond (23.86) Management Fee 0.65% Overnight (19.77) Share Class Base Currency CAD A-1+/P-1 (58.45) Domicile Bermuda Bankers Acceptance (9.89) 2 days - 1 week (44.58) ISIN BMG4641E1416 Share Class Inception Date 08 Dec 1993 Commercial Paper (6.23) 1 week - 1 month (13.49) Fund Size CAD 54,543,167 A-1/P-1 up to 5 days (21.19) Bloomberg Ticker CMYCADR BH CD (1.5) 1 - 3 months (17.51) MLFI - ICE BofA Canadian Dollar Reference Benchmark Overnight Deposit bid Rate Index Time Deposit (19.36) 3 - 6 months (3.82) Manager Edward J Dombrowski A-1/P-1 above 5 days (20.36) HSBC Global Liquidity 6 months - 397 days (0.83) Treasury Bill (39.17) Funds PLC - HSBC Master Fund Name Canadian Dollar Liquidity Top 10 Issuers (%) Fund GOVERNMENT OF CANADA 24.51 Master Fund Size CAD 120,274,512 NATIONAL BANK OF CANADA 9.73 CREDIT AGRICOLE GROUP 9.56 Rating BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 3.35 Moody's Rating 1 Aaa-mf ROYAL BANK OF CANADA 3.33 S&P Rating 1 AAAm CANADIAN IMPERIAL BANK OF COMMERCE 3.33 TORONTO-DOMINION BANK/THE 3.32 Characteristics PROVINCE OF MANITOBA CANADA 3.32 Weighted Average Life 2 48 PROVINCE OF NOVA SCOTIA CANADA 3.32 Weighted Average Maturity 3 48 PROVINCE OF QUEBEC CANADA 3.32 Source: HSBC Global Asset Management, data as at 31 August 2021 Fund Manager Information IMMFA Member 4 01/07/2000 Risk Disclosure 1The “AAAm”, “Aaa-mf” and "AAAmmf" money market fund • The Fund's unit value can go up as well as down, and any capital invested in the Fund may be at risk. -

Hsbc Bank Bermuda Limited

February 24th 2017 HSBC BANK BERMUDA LIMITED “HSBC Bermuda” YEAR END 2016 RESULTS - HIGHLIGHTS Consolidated reported net profit of US$117m for the year ended 31 December 2016, an increase of US$30m or 34% compared with the prior year. Consolidated net operating income of US$262m for the year ended 31 December 2016, a decrease of US$6m or 2% compared with the prior year. Consolidated operating expenses for the year ended 31 December 2016 decreased by US$10m or 6% to US$166m. Excluding impairment on buildings of US$21m, consolidated operating expenses for the year ended 31 December 2016 were US$145m, a decrease of US$31m or 18%. Total assets of US$9,757m at 31 December 2016, decreased by 19% compared with the prior year end, mainly due to the disposal of our Private Banking operations. Total loans and advances to customers were US$2,290m at 31 December 2016, a decrease of 7% compared with the prior year end. Total loan impairment provisions as a percentage of total gross loans and advances to customers decreased to 3% at 31 December 2016, compared to 5% for the prior year. Total capital adequacy ratio is 24% at 31 December 2016, compared to 22% at 31 December 2015. HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited’s (HSBC Bermuda) total operating income before loan impairment charges reduced by US$23m or 8% reflecting the disposal of the bank’s Private Banking operations at the end of April 2016. Net operating income decreased by only US$6m as the business benefited from the impact of lower loan impairment charges. -

Epoch Investments Funds P.L.C. Prospectus

If you are in any doubt about the contents of this Prospectus, the risks involved in investing in the Company or the suitability for you of investment in the Company, you should consult your stock broker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent financial adviser. Prices for Shares in the Company may fall as well as rise. The Directors of the Company whose names appear under the heading “Management and Administration” in this Prospectus accept responsibility for the information contained in this Prospectus. To the best of the knowledge and belief of the Directors (who have taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case) the information contained in this Prospectus is in accordance with the facts in all material respects and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. The Directors accept responsibility accordingly. Epoch Investment Funds plc An umbrella company with segregated liability between Funds (an open-ended umbrella investment company with variable capital and segregated liability between Funds incorporated with limited liability in Ireland under the Companies Act 2014 with registration number 519955 and established as an undertaking for collective investment in transferable securities pursuant to the European Communities (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) Regulations, 2011 (S.I. No. 352 of 2011). P R O S P E C T U S The date of this Prospectus is 26 November, 2020. 1 /8071528v1 IMPORTANT INFORMATION This Prospectus should be read in conjunction with the Section entitled “Definitions”. The Prospectus This Prospectus describes Epoch Investment Funds plc, an open-ended umbrella investment company incorporated with variable capital in Ireland and authorised by the Central Bank as an undertaking for collective investment in transferable securities pursuant to the European Communities (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) Regulations, 2011 (S.I.