Notes on Special Functions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics 412 Partial Differential Equations

Mathematics 412 Partial Differential Equations c S. A. Fulling Fall, 2005 The Wave Equation This introductory example will have three parts.* 1. I will show how a particular, simple partial differential equation (PDE) arises in a physical problem. 2. We’ll look at its solutions, which happen to be unusually easy to find in this case. 3. We’ll solve the equation again by separation of variables, the central theme of this course, and see how Fourier series arise. The wave equation in two variables (one space, one time) is ∂2u ∂2u = c2 , ∂t2 ∂x2 where c is a constant, which turns out to be the speed of the waves described by the equation. Most textbooks derive the wave equation for a vibrating string (e.g., Haber- man, Chap. 4). It arises in many other contexts — for example, light waves (the electromagnetic field). For variety, I shall look at the case of sound waves (motion in a gas). Sound waves Reference: Feynman Lectures in Physics, Vol. 1, Chap. 47. We assume that the gas moves back and forth in one dimension only (the x direction). If there is no sound, then each bit of gas is at rest at some place (x,y,z). There is a uniform equilibrium density ρ0 (mass per unit volume) and pressure P0 (force per unit area). Now suppose the gas moves; all gas in the layer at x moves the same distance, X(x), but gas in other layers move by different distances. More precisely, at each time t the layer originally at x is displaced to x + X(x,t). -

Chapter 9 Some Special Functions

Chapter 9 Some Special Functions Up to this point we have focused on the general properties that are associated with uniform convergence of sequences and series of functions. In this chapter, most of our attention will focus on series that are formed from sequences of functions that are polynomials having one and only one zero of increasing order. In a sense, these are series of functions that are “about as good as it gets.” It would be even better if we were doing this discussion in the “Complex World” however, we will restrict ourselves mostly to power series in the reals. 9.1 Power Series Over the Reals jIn this section,k we turn to series that are generated by sequences of functions :k * ck x k0. De¿nition 9.1.1 A power series in U about the point : + U isaseriesintheform ;* n c0 cn x : n1 where : and cn, for n + M C 0 , are real constants. Remark 9.1.2 When we discuss power series, we are still interested in the differ- ent types of convergence that were discussed in the last chapter namely, point- 3wise, uniform and absolute. In this context, for example, the power series c0 * :n t U n1 cn x is said to be3pointwise convergent on a set S 3if and only if, + * :n * :n for each x0 S, the series c0 n1 cn x0 converges. If c0 n1 cn x0 369 370 CHAPTER 9. SOME SPECIAL FUNCTIONS 3 * :n is divergent, then the power series c0 n1 cn x is said to diverge at the point x0. -

Special Functions

Chapter 5 SPECIAL FUNCTIONS Chapter 5 SPECIAL FUNCTIONS table of content Chapter 5 Special Functions 5.1 Heaviside step function - filter function 5.2 Dirac delta function - modeling of impulse processes 5.3 Sine integral function - Gibbs phenomena 5.4 Error function 5.5 Gamma function 5.6 Bessel functions 1. Bessel equation of order ν (BE) 2. Singular points. Frobenius method 3. Indicial equation 4. First solution – Bessel function of the 1st kind 5. Second solution – Bessel function of the 2nd kind. General solution of Bessel equation 6. Bessel functions of half orders – spherical Bessel functions 7. Bessel function of the complex variable – Bessel function of the 3rd kind (Hankel functions) 8. Properties of Bessel functions: - oscillations - identities - differentiation - integration - addition theorem 9. Generating functions 10. Modified Bessel equation (MBE) - modified Bessel functions of the 1st and the 2nd kind 11. Equations solvable in terms of Bessel functions - Airy equation, Airy functions 12. Orthogonality of Bessel functions - self-adjoint form of Bessel equation - orthogonal sets in circular domain - orthogonal sets in annular fomain - Fourier-Bessel series 5.7 Legendre Functions 1. Legendre equation 2. Solution of Legendre equation – Legendre polynomials 3. Recurrence and Rodrigues’ formulae 4. Orthogonality of Legendre polynomials 5. Fourier-Legendre series 6. Integral transform 5.8 Exercises Chapter 5 SPECIAL FUNCTIONS Chapter 5 SPECIAL FUNCTIONS Introduction In this chapter we summarize information about several functions which are widely used for mathematical modeling in engineering. Some of them play a supplemental role, while the others, such as the Bessel and Legendre functions, are of primary importance. These functions appear as solutions of boundary value problems in physics and engineering. -

The Calculus of Trigonometric Functions the Calculus of Trigonometric Functions – a Guide for Teachers (Years 11–12)

1 Supporting Australian Mathematics Project 2 3 4 5 6 12 11 7 10 8 9 A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 Calculus: Module 15 The calculus of trigonometric functions The calculus of trigonometric functions – A guide for teachers (Years 11–12) Principal author: Peter Brown, University of NSW Dr Michael Evans, AMSI Associate Professor David Hunt, University of NSW Dr Daniel Mathews, Monash University Editor: Dr Jane Pitkethly, La Trobe University Illustrations and web design: Catherine Tan, Michael Shaw Full bibliographic details are available from Education Services Australia. Published by Education Services Australia PO Box 177 Carlton South Vic 3053 Australia Tel: (03) 9207 9600 Fax: (03) 9910 9800 Email: [email protected] Website: www.esa.edu.au © 2013 Education Services Australia Ltd, except where indicated otherwise. You may copy, distribute and adapt this material free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes, provided you retain all copyright notices and acknowledgements. This publication is funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Supporting Australian Mathematics Project Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute Building 161 The University of Melbourne VIC 3010 Email: [email protected] Website: www.amsi.org.au Assumed knowledge ..................................... 4 Motivation ........................................... 4 Content ............................................. 5 Review of radian measure ................................. 5 An important limit .................................... -

![[AVV5] We Studied Classical Special Functions, Such As the Gamma Function, the Hypergeometric Function 2F1, and the Complete Elliptic Inte- Grals](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1630/avv5-we-studied-classical-special-functions-such-as-the-gamma-function-the-hypergeometric-function-2f1-and-the-complete-elliptic-inte-grals-1241630.webp)

[AVV5] We Studied Classical Special Functions, Such As the Gamma Function, the Hypergeometric Function 2F1, and the Complete Elliptic Inte- Grals

CONFORMAL GEOMETRY AND DYNAMICS An Electronic Journal of the American Mathematical Society Volume 11, Pages 250–270 (November 8, 2007) S 1088-4173(07)00168-3 TOPICS IN SPECIAL FUNCTIONS. II G. D. ANDERSON, M. K. VAMANAMURTHY, AND M. VUORINEN Dedicated to Seppo Rickman and Jussi V¨ais¨al¨a. Abstract. In geometric function theory, conformally invariant extremal prob- lems often have expressions in terms of special functions. Such problems occur, for instance, in the study of change of euclidean and noneuclidean distances under quasiconformal mappings. This fact has led to many new results on special functions. Our goal is to provide a survey of such results. 1. Introduction In our earlier survey [AVV5] we studied classical special functions, such as the gamma function, the hypergeometric function 2F1, and the complete elliptic inte- grals. In this survey our focus is different: We will concentrate on special functions that occur in the distortion theory of quasiconformal maps. The definitions of these functions involve the aforementioned functions, and therefore these two surveys are closely connected. However, we hope to minimize overlap with the earlier survey. Extremal problems of geometric function theory lead naturally to the study of special functions. L. V. Ahlfors’s book [Ah] on quasiconformal mappings, where the extremal length of a curve family is a crucial tool, discusses among other things the extremal problems of Gr¨otzsch and Teichm¨uller and provides methods for studying the boundary correspondence under quasiconformal automorphisms of the upper half plane or the unit disk. These problems have led to many ramifications and have greatly stimulated later research. -

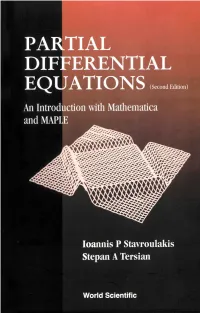

Partial Differential Equations: an Introduction with Mathematica And

PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS (Second Edition) An Introduction with Mathernatica and MAPLE This page intentionally left blank PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS (Scond Edition) An Introduction with Mathematica and MAPLE Ioannis P Stavroulakis University of Ioannina, Greece Stepan A Tersian University of Rozousse, Bulgaria WeWorld Scientific NEW JERSEY 6 LONDON * SINGAPORE * BElJlNG SHANGHAI * HONG KONG * TAIPEI CHENNAI Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Re. Ltd. 5 Toh Tuck Link, Singapore 596224 USA ofice: Suite 202, 1060 Main Street, River Edge, NJ 07661 UK ofice: 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS An Introduction with Mathematica and Maple (Second Edition) Copyright 0 2004 by World Scientific Publishing Co. Re. Ltd. All rights reserved. This book or parts thereoj may not be reproduced in anyform or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the Publisher. For photocopying of material in this volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. In this case permission to photocopy is not required from the publisher. ISBN 981-238-815-X Printed in Singapore. To our wives Georgia and Mariam and our children Petros, Maria-Christina and Ioannis and Takuhi and Lusina This page intentionally left blank Preface In this second edition the section “Weak Derivatives and Weak Solutions” was removed to Chapter 5 to be together with advanced concepts such as discontinuous solutions of nonlinear conservation laws. -

ON MEANS, POLYNOMIALS and SPECIAL FUNCTIONS Johan Gielis

THE TEACHING OF MATHEMATICS 2014, Vol. XVII, 1, pp. 1–20 ON MEANS, POLYNOMIALS AND SPECIAL FUNCTIONS Johan Gielis, Rik Verhulst, Diego Caratelli, Paolo E. Ricci, and Ilia Tavkhelidze Abstract. We discuss how derivatives can be considered as a game of cubes and beams, and of geometric means. The same principles underlie wide classes of polynomials. This results in an unconventional view on the history of the differentiation and differentials. MathEduc Subject Classification: F50, H20 MSC Subject Classification: 97E55, 97H25, 51M15 Key words and phrases: Derivative; polynomial; special function; arithmetic, geometric and harmonic means. 1. On derivation and derivatives In On Proof and Progress in Mathematics William Thurston describes how people develop an “understanding” of mathematics [31]. He uses the example of derivatives, that can be approached from very different viewpoints, allowing individuals to develop their own understanding of derivatives. “The derivative can be thought of as: (1) Infinitesimal: the ratio of the infinitesimal change in the value of a function to the infinitesimal change in a function. (2) Symbolic: the derivative of xn is nxn¡1, the derivative of sin (x) is cos (x), the derivative of f ± g is f 0 ± g £ g0, etc ::: (3) Logical: f 0 (x) = d if and only if for every ² there is a ±, such that 0 < j∆xj < ± when ¯ ¯ ¯f(x + ∆x) ¡ f(x) ¯ ¯ ¡ d¯ < ± 1 ¯ ∆x ¯ (4) Geometric: the derivative is the slope of a line tangent to the graph of the function, if the graph has a tangent. (5) Rate: the instantaneous speed of f (t) = d, when t is time. -

Solutions to Differential Equations: Special Functions

Solutions to Differential Equations: Special Functions 1 Visualizing a few special functions 2 Lecture-26.nb Bessel's equation ‡ Bessel's equation is a second-order ODE having the following form, with the parameter n being real and nonnegative. In[155]:= 1 BesselODE = x2 y'' x + x y' x + x2 - n2 y x ã 0 @ D @ D H L @ D Lecture-26.nb 3 Out[155]= x2 - n2 y x + x y¢ x + x2 y¢¢ x ä 0 Bessel'sI equationM @ arisesD in@ problemsD @in Dheat conduction and mass diffusion for prob- lems with cylindrical symmetry (and many other situations). It's solution is a linear combination of two special functions called Bessel functions of the first kind, BesselJ in Mathematica, and Bessel functions of the second kind, BesselY in Mathematica. 4 Lecture-26.nb In[156]:= 2 DSolve BesselODE, y x , x Out[156]= @ y x Æ BesselJ@ D n,D x C 1 + BesselY n, x C 2 88 @ D @ D @ D @ D @ D<< Lecture-26.nb 5 ‡ The functions BesselJ and BesselY can be evaluated numerically and of course Mathematica has this capability built-in. In[157]:= MyPlotStyle HowMany_Integer := 3 Table Hue 0.66* i HowMany , Thickness 0.01 , i, 0, HowMany In[158]:= @ D 4 Plot BesselJ 0, x , BesselY 0, x , x, 0, 20 , PlotStyle Ø MyPlotStyle 2 @8 @ ê D @ D< 8 <D @8 @ 1D @ D< 8 < @ DD 0.5 5 10 15 20 -0.5 -1 6 Lecture-26.nb 1 0.5 5 10 15 20 -0.5 -1 1 0.5 Lecture-26.nb 7 5 10 15 20 -0.5 -1 1 0.5 5 10 15 20 8 -0.5 Lecture-26.nb -1 Out[158]= Ö Graphics Ö In[159]:= 5 Plot BesselJ 5, x , BesselY 5, x , x, 0, 20 , PlotStyle Ø MyPlotStyle 2 @8 @ D @ D< 8 < @ DD 5 10 15 20 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 Lecture-26.nb 9 5 10 15 -

4 Trigonometry and Complex Numbers

4 Trigonometry and Complex Numbers Trigonometry developed from the study of triangles, particularly right triangles, and the relations between the lengths of their sides and the sizes of their angles. The trigono- metric functions that measure the relationships between the sides of similar triangles have far-reaching applications that extend far beyond their use in the study of triangles. Complex numbers were developed, in part, because they complete, in a useful and ele- gant fashion, the study of the solutions of polynomial equations. Complex numbers are useful not only in mathematics, but in the other sciences as well. Trigonometry Most of the trigonometric computations in this chapter use six basic trigonometric func- tions The two fundamental trigonometric functions, sine and cosine, can be de¿ned in terms of the unit circle—the set of points in the Euclidean plane of distance one from the origin. A point on this circle has coordinates +frv w> vlq w,,wherew is a measure (in radians) of the angle at the origin between the positive {-axis and the ray from the ori- gin through the point measured in the counterclockwise direction. The other four basic trigonometric functions can be de¿ned in terms of these two—namely, vlq { 4 wdq { @ vhf { @ frv { frv { frv { 4 frw { @ fvf { @ vlq { vlq { 3 ?w? For 5 , these functions can be found as a ratio of certain sides of a right triangle that has one angle of radian measure w. Trigonometric Functions The symbols used for the six basic trigonometric functions—vlq, frv, wdq, frw, vhf, fvf—are abbreviations for the words cosine, sine, tangent, cotangent, secant, and cose- cant, respectively.You can enter these trigonometric functions and many other functions either from the keyboard in mathematics mode or from the dialog box that drops down when you click or choose Insert + Math Name. -

C 1 : Power Series Solutions and Special Functions

CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 POWER SERIES SOLUTIONS 03 1.1 INTRODUCTION 03 1.2 POWER SERIES SOLUTIONS 04 1.3 REGULAR SINGULAR POINTS – 05 FROBENIUS SERIES SOLUTIONS 1.4 GAUSS’S HYPER GEOMETRIC EQUATION 07 1.5 THE POINT AT INFINITY 09 CHAPTER 2 SPECIAL FUNCTIONS 11 2.1 LEGENDRE POLYNOMIALS 11 2.2 BESSEL FUNCTIONS – GAMMA FUNCTION 15 CHEPTER 3 SYSTEMS OF FIRST ORDER EQUATIONS 20 3.1 LINEAR SYSTEMS 20 3.2 HOMOGENEOUS LINEAR SYSTEMS WITH 21 CONSTANT COEFFICIENTS 3.3 NON LINEAR SYSTEM 24 CHAPTER 4 NON LIEAR EQUATIONS 26 4.1 AUTONOMOUS SYSTEM 26 4.2 CRITICAL POINTS & STABILITY 28 4.3 LIAPUNOV’S DIRECT METHOD 31 4.4 SIMPLE CRITICAL POINTS -NON LINEAR SYSTEM 34 CHAPTER 5 FUNDAMENTAL THEOREMS 38 5.1 THE METHOD OF SUCCESSIVE APPROXIMATIONS 38 5.2 PICARD’S THEOREM 39 Differential Equations 3 CHAPTER 6 FIRST ORDER PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS 46 6.1 INTRODUCTION – REVIEW 46 6.2 FORMATION OF FIRST ORDER PDE 48 6.3 CLASSIFICATION OF INTEGRALS 50 6.4 LINEAR EQUATIONS 54 6.5 PFAFFIAN DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS 56 6.6 CHARPIT’S METHOD 62 6.7 JACOBI’S METHOD 66 6.8 CAUCHY PROBLEM 70 6.9 GEOMETRY OF SOLUTIONS 74 CHAPTER 7 SECOND ORDER PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS 7.1 CLASSIFICATION 78 7.2 ONE DIMENSIONAL WAVE EQUATION 81 7.3 RIEMANN’S METHOD 87 7.4 LAPLACE EQUATION 89 7.5 HEAT CONDUCTION PROBLEM 95 - 98 Differential Equations 4 CHAPTER 1 POWER SERIES SOLUTIONS AND SPECIAL FUNCTIONS 1.1 Introduction An algebraic function is a polynomial, a rational function, or any function that satisfies a polynomial equation whose coefficients are polynomials. -

Fractional Calculus and Special Functions

LECTURE NOTES ON MATHEMATICAL PHYSICS Department of Physics, University of Bologna, Italy URL: www.fracalmo.org FRACTIONAL CALCULUS AND SPECIAL FUNCTIONS Francesco MAINARDI Department of Physics, University of Bologna, and INFN Via Irnerio 46, I{40126 Bologna, Italy. [email protected] [email protected] Contents (pp. 1 { 62) Abstract . p. 1 A. Historical Notes and Introduction to Fractional Calculus . p. 2 B. The Liouville-Weyl Fractional Calculus . p. 8 C. The Riesz-Feller Fractional Calculus . p.12 D. The Riemann-Liouville Fractional Calculus . p.18 E. The Gr¨unwald-Letnikov Fractional Calculus . p.22 F. The Mittag-Leffler Functions . p.26 G. The Wright Functions . p.42 References . p.52 The present Lecture Notes are related to a Mini Course on Introduction to Fractional Calculus delivered by F. Mainardi, at BCAM, Bask Cen- tre for Applied Mathematics, in Bilbao, Spain on March 11-15, 2013, see http://www.bcamath.org/en/activities/courses. The treatment reflects the research activity of the Author carried out from the academic year 1993/94, mainly in collaboration with his students and with Rudolf Gorenflo, Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at the Freie Universt¨at,Berlin. ii Francesco MAINARDI c 2013 Francesco Mainardi FRACTIONAL CALCULUS AND SPECIAL FUNCTIONS 1 FRACTIONAL CALCULUS AND SPECIAL FUNCTIONS Francesco MAINARDI Department of Physics, University of Bologna, and INFN Via Irnerio 46, I{40126 Bologna, Italy. [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The aim of these introductory lectures is to provide the reader with the essentials of the fractional calculus according to different approaches that can be useful for our applications in the theory of probability and stochastic processes. -

A Table of Integrals of the Error Functions*

JOURNAL OF RESEAR CH of the Natiana l Bureau of Standards - B. Mathematical Sciences Vol. 73B, No. 1, January-March 1969 A Table of Integrals of the Error Functions* Edward W. Ng** and Murray Geller** (October 23, 1968) This is a compendium of indefinite and definite integrals of products of the Error function with elementary or transcendental functions. A s'ubstantial portion of the results are ne w. Key Words: Astrophysics; atomic physics; Error functions; indefi nite integrals; special functions; statistical analysis. 1. Introduction Integrals of the error function occur in a great variety of applicati ons, us ualJy in problems involvin g multiple integration where the integrand contains expone ntials of the squares of the argu me nts. Examples of applications can be cited from atomic physics [16),1 astrophysics [13] , and statistical analysis [15]. This paper is an attempt to give a n up-to-date exhaustive tabulation of s uch integrals. All formulas for indefi nite integrals in sections 4.1, 4.2, 4.5, a nd 4.6 below were derived from integration by parts and c hecked by differe ntiation of the resulting expressions_ Section 4.3 and the second hali' of 4.5 cover all formulas give n in [7] , with omission of trivial duplications and with a number of additions; section 4.4 covers essentially formulas give n in [4], Vol. I, pp. 233-235. All these formulas have been re-derived and checked, eithe r from the integral representation or from the hype rgeometric series of the error function. Sections 4.7,4_8 and 4_9 ori ginated in a more varied way.