Revisiting Modern Art in India Prior to Independence: a Capsule Account of Beginnings, Confrontations, Conflicts and Milestones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notification No. 1 Dated : 30-03-2021

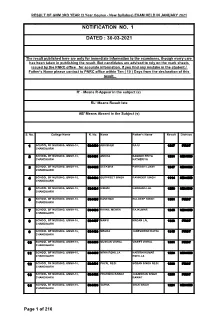

RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 30-03-2021 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject (s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent in the Subject (s) S. No. College Name R. No. Name Father's Name Result Division 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534480 ABHISHEK RAJU 1287 FIRST CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534481 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 1231 SECOND CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534482 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 1247 SECOND CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534483 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 1114 SECOND CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534484 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 1250 SECOND CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534485 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 1381 FIRST CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534486 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 1245 SECOND CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534487 MANSI MADAN LAL 1338 FIRST CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534488 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 1315 FIRST CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534489 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 1301 FIRST CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534490 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 1223 SECOND CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534491 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 1296 FIRST CHANDIGARH 13 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534492 PRATIBHA RAWAT JAGMOHAN SINGH 1266 FIRST CHANDIGARH RAWAT 14 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534493 SAPNA SHER SINGH 1221 SECOND CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 216 RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 S. -

Result of Gnm 1St Year Exam Held in December - 2018

RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 31-05-2019 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject,(s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent S. College Name Roll No Name Father Name Result No. 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483001 ABHISHEK RAJU 354 CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483002 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 315 CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483003 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 334 CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483004 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 312 CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483005 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 332 CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483006 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 366 CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483007 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 328 CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483008 MANSI MADAN LAL 356 CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483009 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 347 CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483010 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 355 CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483011 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 324 CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483012 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 346 CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 304 RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 S. -

Utopias and Dystopias in World Literature

MEJO The MELOW Journal of World Literature Volume 4 February 2020 ISSN: 2581-5768 A peer-refereed journal published annually by MELOW (The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World) Sunny Pleasure Domes and Caves of Ice: Utopias and Dystopias in World Literature Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang Volume Sub-Editors Neela Sarkar Barnali Saha 1 Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang, Professor of English, Guru Gobind Singh IP University, Delhi Email: [email protected] Volume Sub-Editors Neela Sarkar, Associate Professor, New Alipore College, W.B. Email: [email protected] Barnali Saha, Research Scholar, Guru Gobind Singh IP University, Delhi Email: [email protected] Editorial Board: Anil Raina, Professor of English, Panjab University Email: [email protected] Debarati Bandyopadhyay, Professor of English, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Email: [email protected] Himadri Lahiri, Professor of English, University of Burdwan Email: [email protected] Manju Jaidka, Professor, Shoolini University, Solan Email: [email protected] Rimika Singhvi, Associate Professor, IIS University, Jaipur Email: [email protected] Roshan Lal Sharma, Professor, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala Email: [email protected] 2 3 EDITORIAL NOTE MEJO, or the MELOW Journal of World Literature, is a peer-refereed E-journal brought out biannually by MELOW, the Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World. It is a reincarnation of the previous publications brought out in book or printed form by the Society right since its inception in 1998. MELOW is an academic organization, one of the foremost of its kind in India. -

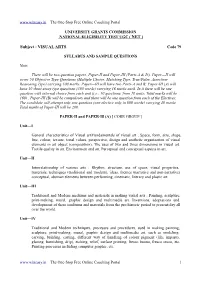

Subject : VISUAL ARTS Code 79

www.wineasy.in – The One-Stop Free Online Coaching Portal UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION NATIONAL ELIGIBILITY TEST UGC ( NET ) Subject : VISUAL ARTS Code 79 SYLLABUS AND SAMPLE QUESTIONS Note: There will be two question papers, Paper-II and Paper-III (Parts-A & I3). Paper—II will cover 50 Objective Type Questions (Multiple Choice, Matching Type, True/False, Assertion- Reasoning Type) carrying 100 marks. Paper—III will have two Parts-A and B; Paper-III (A) will have 10 short essay type questions (300 words) carrying 16 marks each. In it there will be one question with internal choice from each unit (i.e., 10 questions. from 10 units; Total marks will be 160) . Paper-III (B) will be compulsory and there will be one question from each of the Electives. The candidate will attempt only one question (one elective only in 800 words) carrying 40 marks. Total marks of Paper-III will be 200. PAPER-II and PAPER-Ill (A) [ CORE GROUP ] Unit—I General characteristics of Visual art/Fundamentals of visual art : Space, form, size, shape, line, colour, texture, tonal values, perspective, design and aesthetic organization of visual elements in art object (composition). The uses of two and three dimensions in visual art. Tactile quality in art. Environment and art. Perceptual and conceptual aspects in art. Unit—II Interrelationship of various arts : Rhythm, structure, use of space, visual properties. materials, techniques (traditional and modern), ideas, themes (narrative and non-narrative) conceptual, abstract elements between performing, cinematic, literary and plastic art. Unit—III Traditional and Modern mediums and materials in making visual arts : Painting, sculpture, print-making, mural, graphic design and multimedia art. -

Introduction to Indian Art Kl Lifestyle Art Space Presents 3 Indian Artists

INTRODUCTION TO INDIAN ART KL LIFESTYLE ART SPACE PRESENTS 3 INDIAN ARTISTS BY HIRANMAYII AWLI MOHANAN Indian art encompasses a variety of forms and originated about five thousand years ago, sometime during the peak of the Indus Valley civilisation. Largely influenced by a civilisation that came into existence in the 3rd millennium B.C., it blends the spiritual and the sensual, making it rather distinctive in form and appearance. However, progressively, Indian art has undergone several transformations and influenced by various cultures, making it more diverse and more inclusive of its people. PARITOSH SEN Paritosh Sen was a painter, illustrator, tutor and writer, who was a part of the world of Indian art, for close to four decades. He was born in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh on Oct 18, 1919 and was a founding member of the Calcutta Group — an art movement established in 1942 which played an important role in ushering modernism into Indian art. Allured by the pages of the Bengali art journal, Prabasi, Sen ran away to Madras, to learn art. Graduating with a Diploma in Fine Arts from the Government College of Arts and Crafts, Chennai, Sen moved to Calcutta in 1942, where he and a group of young Bengalis formed the Calcutta Group — an association of artists that sought to incorporate contemporary values in Indian art. In 1949, Sen left for Paris to pursue his passion, attending, among other institutes, the Ecole des Beaux Arts. He received a Fellowship for 1970-’71 from the John D. Rockefeller III Fund. The Indian artist’s visit to Paris in 1949 was what got him closer acquainted with European art and its artists. -

Humanties Science (HSS)

DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Course Number & Title: HS 101 (English Communication Skills) L-T-P-C: 2-0-2-0 Type of Letter Grading (Regular Letter Grades / PP or NP Letter Grades): Kind of Proposal (New Course / Revision of Existing Course): Revision of Existing Course Offered as (Compulsory / Elective): Compulsory Offered to: B Tech/B.Des Semester I Offered in (Odd/ Even / Any): Odd Offered by (Name of Department/ Center): Humanities and Social Sciences Pre-Requisite: A Classroom with movable furniture for flipped class ; Multi-media Language Laboratory Preamble / Objectives (Optional): The Course has the following objectives: The Course will help the learners to develop general proficiency in English in terms of listening, speaking, reading and writing, gain confidence to use grammatically accepted English for communication, gain confidence to speak English intelligibly, learn to use self - study strategies, use interpersonal communication skills effectively, become aware of the skills of critical thinking, information transfer and problem solving, develop analytical skills. Course Content/ Syllabus (as a single paragraph if it is not containing more than one subject. Sub-topics/ Sections may be separated by commas(,). Topics may be separated by Semi-Colons(;). Chapters may be separated by Full-Stop(.). While starting with broad heading, it may be indicated with Colon symbol before the topics. For example: Multi- variable Calculus: Limits of functions, Continuity, ……) General proficiency in English and Communication skills: -

Price List 2015.Indd

Lalit Kala Publications 2015 Lalit Kala Akademi Rabindra Bhavan, New Delhi-110001 MONOGRAPHS The monographs in the Lalit Kala Series of Contemporary Indian Art have been undertaken by the Lalit Kala Akademi with the intention of popularising the works of India’s leading painters, sculptors and printmakers. Effort is made to present a bird’s eye view of the development of their artistic career. Each monograph is in the format 17.5 x 12 cms. on foreign art paper. It contains a brief introduction of the artist along with colour plates and b/w illustrations. Monographs Available Rs. 1. Dhanraj Bhagat 50 2. Prodosh Das Gupta 50 3. Biren De 50 4. L. Munuswamy 50 5. K. S. Kulkarni 50 6. Ram Gopal Vijaiwargiya 50 7. S. H. Raza 50 8. Y. K. Shukla 50 9. Ranvir Singh Bisht 50 10. V. P. Karmarkar 50 11. Bimal Das Gupta 50 12. Radhamohan 50 13. Sarat Chandra Debo 50 14. Goverdhan Lal Joshi 50 15. P. T. Reddy 50 16. K. Madhava Menon 50 17. Nicholas Roerich 50 18. Amarnath Sehgal 50 19. Chittaprosad 50 20. Kanwal Krishna & Devyani Krishna 50 21. J. Swaminathan 50 22. Gurcharan Singh 50 23. Piraji Sagara 50 24. M. Reddappa Naidu 50 25. Devki Nandan Sharma 75 26. A. P. Santhanaraj 75 27. R. K. Rao 75 28. Balbir Singh Katt 75 29. Sakti Burman 75 30. Kripal Singh Shekhawat 75 Monographs Large Format (Hard Bound 9”x9”) 31. J. Sultan Ali 100 32. Pilloo Pochkhanawala 100 33. Somnath Hore 100 34. V. S. Gaitonde 100 35. -

Modernisms in India

Modernisms in India Modernisms in India Supriya Chaudhuri The Oxford Handbook of Modernisms Edited by Peter Brooker, Andrzej Gąsiorek, Deborah Longworth, and Andrew Thacker Print Publication Date: Dec 2010 Subject: Literature, Literary Studies - 20th Century Onwards, Literary Studies - Postcolonial Literature Online Publication Date: Sep 2012 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199545445.013.0053 Abstract and Keywords This article examines the history of modernism in India. It suggests that though the dis tinctions between modernity, modernization, and modernism are particularly complicated in the case of India, they remain crucial to a historical understanding of the ‘modern’ in all its senses. The article argues that the characteristic feature of Indian modernism in In dia is that it is manifestly social and historical rather than a hypostasis of the new as in the West. It contends that modernisms in India are deeply implicated in the construction of a secular national identity at home in the world, and in this respect answer a historical need to fashion a style for the modern as it is locally experienced. Keywords: modernism, India, modernization, modernity, national identity, hypostasis THE distinctions between modernity, modernization, and modernism are particularly com plicated in the case of India, but remain crucial to a historical understanding of the ‘mod ern’ in all its senses. Modernity, as a social and intellectual project, and modernization, as its means, are associated with the influence in India of Europe and of Enlightenment ra tionality from the eighteenth century onwards. Modernism, as an aesthetic, is far more limited in period and scope. Nevertheless, just as recent cultural criticism has proposed the existence of ‘alternative modernities’1 not native to the West, so too our attention has been drawn to ‘alternative modernisms’, or ‘modernisms at large’.2 The question of peri odicity, as of location, is complicated by the historical fact that modernism as an aesthetic was simultaneously restricted and elitist, and international and democratic. -

Bva Cbcs Syllabus 2.Pdf

Telephone No. 2419677/2419361 e-mail: [email protected] Fax: 0821-2419363/2419301 www.uni-mysore.ac.in UNIVERSITY OF MYSORE Estd. 1916 VishwavidyanilayaKaryasoudha Crawford Hall, Mysuru- 570 005 No.AC6/32/2018-19 Dated: 15th June 2018 NOTIFICATION Sub: To Change the nomenclature from Three year BFA (Annual Scheme) to Four year B.V.A (Semester Scheme) and Syllabus, Scheme of Examination as per CBCS Pattern from the academic year 2018-19. Ref: 1. Decision of the Board of Studies in Visual Arts (CB) held on 09-03-2018. 2. Decision of the Faculty of Arts Meeting held on 20-04- 2018. 3. Decision of the Deans committee Meeting held on 22.05.2018. ***** The Board of Studies in Visual Arts (CB) which met on 09th March 2018 has recommended To Change the nomenclature from Three year BFA (Annual Scheme) to Four year B.V.A of (Semester Scheme) and Syllabus, Scheme of Examination as per CBCS Pattern from the academic year 2018-19. The Faculty of Arts and the Deans Committee held on 20.04.2018 and 22.05.2018 respectively have approved the above said proposal with pending ratification of Academic Council and the same is hereby notified. The contents may be downloaded from the University Website i.e.,www.uni- mysore.ac.in Sd/- Deputy Registrar(Academic) Draft Approved by the Registrar To: 1. The Registrar (Evaluation), University of Mysore, Mysuru. 2. The Dean, Faculty of Arts, Department of Studies in English,Manasagangotri, Mysuru. 3. The Principal, Fine Arts College, Manasagangothri, Mysuru. 4. The Chairman, Board of Studies in Fine Arts, Fine Arts College, Manasagangotri, Mysuru. -

The Silver Series - 3

DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 THE SILVER SERIES EDITION 3 6 - 10 JULY 2020 10% SALE PROCEEDS TO 1 DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 THE SILVER SERIES EDITION 3 100 ARTISTS ² 100 WORKS Modern and Contemporary Indian Art 6 - 10 JULY 2020 FIXED-PRICE ONLINE SALE The Silver Series is DAG’s initiative towards raising funds for charity through its fixed-price online sales For further information please contact us at [email protected] 1 DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 FROM ASHISH ANAND’S DESK Hundreds of great artists have marked every decade of the twentieth century, which is why I have always been surprised at the invisibility of so many of our masters. Painters, sculptors, printmakers, teachers, they have made a name for themselves, but in the absence of their work being shown nationally—rather than regionally, as has been the norm—many have remained outside mainstream discourse. At DAG, it has been our effort to ensure their rediscovery and recognition, something we continue to do with our Silver Series, fixed-price online sales. The outstanding success of the first two editions is an indicator that art-lovers also have an appreciation for lesser-known names, as well as those whose works do not appear frequently in the market. Our endeavour with every edition will be to continue to surprise you with the mix of artists and the quality of their work. I hope the additions in this edition will bring you joy. If you miss any favourites, I assure you that you will find them in subsequent editions. -

Government College of Art and Craft Calcutta Four Year (Eight Semesters) B.F.A

GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ART AND CRAFT CALCUTTA FOUR YEAR (EIGHT SEMESTERS) B.F.A. (HONOURS) C.B.C.S. SYLLABUS DEPARTMENT OF PAINTING [P (Practical): 1 Credit = 2 Contact Hours. TH (Theoretical): 1 Credit = 1 Hour] Semester 3 Course Course paper Credit Marks Examination System/ code Detailed Course of Studies/ Nature of Studies Assessment Procedure PCC 3.1 Composition : 04 50 Practical paper. Understanding of Space, Form, Construction, Line, To be examined by a Colour, Texture through study of elements around us. board of at least one External Learning from old and contemporary masters through and their works and experimenting with suitable media on one Internal Examiner. paper/ paper board such as Water colour, UE : 80 % Marks Gouache/Opaque Water colour, Pastel, collage etc. IE : 10 % Marks Percentage of Attendants: 10% Marks PCC 3.2 Object study in Oil : 04 50 Practical paper. Composed objects such as drapery, metal/ wood/ To be examined by a stone/ glass/ porcelain/ ceramic/ terracotta (vas, pot, board of at least one External mask, toy, etc). and Monochrome/ Multi colour in oil colour. Detail one Internal Examiner. observation of materialistic differences between UE : 80 % Marks different objects, arrangement, tonal variations, IE : 10 % Marks modulation, chiaroscuro/ light & shade and reflection Percentage of Attendants: of different lights. 10% Marks PCC 3.3 Study from nature in Oil: 04 50 Practical paper. Outdoor/ indoor study in oil on canvas. To be examined by a Detail observation of environment, perspective, board of at least one External arrangement of living and manmade objects, and application of pigments, tonal variations, brush one Internal Examiner. -

Download Abby Grey and Indian Modernism Checklist

Abby Grey and Indian Modernism: Selections from the NYU Art Collection Grey Art Gallery Exhibition Checklist 1. Ambadas Faceless Divinity, 1967 Oil on canvas 60 1/8 x 36 in. (152.7 x 91.4 cm) G1975.184 Work ID: 1 2. Jaya Appasamy Ethonic Figures, 1967 Oil on canvas 35 3/4 x 48 1/4 in. (90.8 x 122.6 cm) G1975.186 Work ID: 3 3. Prabhakar Barwe Yantra III, 1964 Watercolor, ink, and silver paper on paper 19 3/8 x 29 1/8 in. (49.2 x 74 cm) G1975.152 Work ID: 5 4. Prabhakar Barwe King and Queen of Spades, 1967 Paper and oil on canvas 39 3/16 x 54 1/8 in. (99.5 x 137.5 cm) G1975.188 Work ID: 6 1 5. Dhanraj Bhagat Symbols, 1968 Wood and nails 48 x 7 3/4 x 4 3/4 in. (121.9 x 19.7 x 12.1 cm) G1975.187 Work ID: 4 6. Shanti Dave Composition #1, 1968 Oil and wax on canvas 31 3/4 x 16 inches (80.6 x 40.6 cm) G1975.196 Work ID: 3 7. Satish Gujral Christ in the Desert, 1960 Oil on canvas 20 3/4 x 37 1/4 in. (52.7 x 94.6 cm) G1975.156 Work ID: 8 8. Somnath Hore Birth of a White Rose, 1961 Etching on paper 19 3/4 x 17 3/4 in. (50.2 x 45.1 cm) Edition, 4/10 G1975.157 Work ID: 9 9. Somnath Hore Shepherd, 1965 Etching on paper 8 x 9 7/8 in.