Sharing by the Concerned Citizens of Abra for Good Government, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quintin Paredes 1884–1973

H former members 1900–1946 H Quintin Paredes 1884–1973 RESIDENT COMMISSIONER 1935–1938 NACIONALISTA FROM THE PHILIPPINES s the first Resident Commissioner to represent eventually moved to Manila and studied law under the the Philippines after it became a commonwealth direction of another of his brothers, Isidro. He worked during of the United States, Quintin Paredes worked the day, studied at night, and after passing the bar exam, toA revise the economic relationship between his native Paredes briefly took a job with the Filipino government in archipelago and the mainland. Paredes championed Manila before moving to the private sector.4 Paredes married Philippine independence, constantly reminding policymakers Victoria Peralta, and the couple had 10 children.5 of his home’s history as a valuable and vital trading partner. In 1908 Paredes joined the solicitor general’s office In testimony before congressional committees and in in Manila as a prosecuting attorney and rapidly rose to speeches on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, the solicitor general post in 1917. The very next year, Paredes countered common misconceptions about Filipinos Paredes accepted the job as attorney general, becoming and worked to place the islands on stable economic footing as the Philippines’ top lawyer. Within two years, he became they moved toward independence. secretary of justice in the cabinet of Governor General One of 10 children, Quintin Paredes was born in the Francis Burton Harrison, a former Member of the U.S. northwestern town of Bangued, in the Philippines’ Abra House of Representatives from New York. President Province, on September 9, 1884, to Juan Felix and Regina Woodrow Wilson nominated Paredes to serve as an Babila Paredes. -

BSP Holdings 2012 Production ABRA APAYAO BENGUET SAFETY

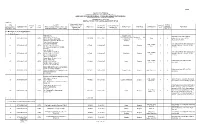

Mineral Production III. Exports Environmental Protection and Enhancement Program A. Metallic Quantity Value (PhP) Commodity/ Quantity Value (PhP) Value (US$) AEPEP Commitment Gold (Kg) 3,400.69 8,326,807,058.00 Destination Company 2012 Commitment Silver (Kg) 3,680.31 97,288,217.00 A. Gold (kg) 3,080.64 6,998,402,339 412,991,653 (PhP) Copper (DMT) 40,532.00 3,802,572,437.00 China, Japan, Philex Mining Corporation 261,213,336.00 7,482.13 7,398,440.00 London, Canada, SSM-Gold (gms) Lepanto Consolidated Mining Company 106,250,000.00 B. Non-Metallic Switzerland ML Carantes Devt. & Gen. Const. Entp. 308,154.00 Quicklime (MT) 8,884.71 63,616,454.14 B. Silver (kg) 3,660.40 215,133,289.40 10,980,778 Slakelime (MT) 461.11 2,377,603.85 China, Japan, Mountain Rock Aggregates 440,500.00 London, Canada, I. Large Scale Metallic Non-Metallic BC-BAGO 2,111,000.00 Mining Switzerland A. Number of 3 1 C. Copper (DMT) 40,136 3,426,102,554 60,400,939 BC-ACMP 4,802,000.00 Producers Japan Itogon Suyoc Resources, Inc. 1,385,310.00 B. Total Area 1,637.0800 19.09 IV. Sand & Gravel TOTAL 376,113,850.00 Covered (Has.) Province ABRA APAYAO BENGUET C. Employment 4,953 Males 406 Females A. Quantity Produced 35,191 250,318 66,553 D. Local Sales (PhP) (cu.m.) Gold (Kg) 194.52 437,814,493.00 B. Value (PhP) 1,294,911 100,127,312 12,235,927 SAFETY STATISTICS January-December 2012 SSM-Gold (gms) 7,705.13 7,875,105.00 C. -

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, Dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1. Pateros 1st CAR ABRA 1 Baay-Licuan 5th 2 Bangued 1st 3 Boliney 5th 4 Bucay 5th 5 Bucloc 6th 6 Daguioman 5th 7 Danglas 5th 8 Dolores 5th 9 La Paz 5th 10 Lacub 5th 11 Lagangilang 5th 12 Lagayan 5th 13 Langiden 5th 14 Luba 5th 15 Malibcong 5th 16 Manabo 5th 17 Penarrubia 6th 18 Pidigan 5th 19 Pilar 5th 20 Sallapadan 5th 21 San Isidro 5th 22 San Juan 5th 23 San Quintin 5th 24 Tayum 5th 25 Tineg 2nd 26 Tubo 4th 27 Villaviciosa 5th APAYAO 1 Calanasan 1st 2 Conner 2nd 3 Flora 3rd 4 Kabugao 1st 5 Luna 2nd 6 Pudtol 4th 7 Sta. Marcela 4th BENGUET 1. Atok 4th 2. Bakun 3rd 3. Bokod 4th 4. Buguias 3rd 5. Itogon 1st 6. Kabayan 4th 7. Kapangan 4th 8. Kibungan 4th 9. La Trinidad 1st 10. Mankayan 1st 11. Sablan 5th 12. Tuba 1st blgf/ltod/updated 1 of 30 updated 4-27-16 Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 13. Tublay 5th IFUGAO 1 Aguinaldo 2nd 2 Alfonso Lista 3rd 3 Asipulo 5th 4 Banaue 4th 5 Hingyon 5th 6 Hungduan 4th 7 Kiangan 4th 8 Lagawe 4th 9 Lamut 4th 10 Mayoyao 4th 11 Tinoc 4th KALINGA 1. Balbalan 3rd 2. Lubuagan 4th 3. Pasil 5th 4. Pinukpuk 1st 5. Rizal 4th 6. Tanudan 4th 7. Tinglayan 4th MOUNTAIN PROVINCE 1. Barlig 5th 2. Bauko 4th 3. Besao 5th 4. -

Chronic Food Insecurity Situation Overview in 71 Provinces of the Philippines 2015-2020

Chronic Food Insecurity Situation Overview in 71 provinces of the Philippines 2015-2020 Key Highlights Summary of Classification Conclusions Summary of Underlying and Limiting Factors Out of the 71 provinces Severe chronic food insecurity (IPC Major factors limiting people from being food analyzed, Lanao del Sur, level 4) is driven by poor food secure are the poor utilization of food in 33 Sulu, Northern Samar consumption quality, quantity and provinces and the access to food in 23 provinces. and Occidental Mindoro high level of chronic undernutrition. Unsustainable livelihood strategies are major are experiencing severe In provinces at IPC level 3, quality of drivers of food insecurity in 32 provinces followed chronic food insecurity food consumption is worse than by recurrent risks in 16 provinces and lack of (IPC Level 4); 48 quantity; and chronic undernutrition financial capital in 17 provinces. provinces are facing is also a major problem. In the provinces at IPC level 3 and 4, the majority moderate chronic food The most chronic food insecure of the population is engaged in unsustainable insecurity (IPC Level 3), people tend to be the landless poor livelihood strategies and vulnerable to seasonal and 19 provinces are households, indigenous people, employment and inadequate income. affected by a mild population engaged in unsustainable Low-value livelihood strategies and high chronic food insecurity livelihood strategies such as farmers, underemployment rate result in high poverty (IPC Level 2). unskilled laborers, forestry workers, incidence particularly in Sulu, Lanao del Sur, Around 64% of the total fishermen etc. that provide Maguindanao, Sarangani, Bukidnon, Zamboanga population is chronically inadequate and often unpredictable del Norte (Mindanao), Northern Samar, Samar food insecure, of which income. -

The People of the Mountains

The People of the Mountains Mata, Ritchelle Abigail P. Polido, Pristine Joy B. TINGUE = mountaineers Therefore, TINGGUIAN means “the people of the mountains” ITNEG: Samtoy (Ilocano) name for tingguians LOKASYON Apay nga awan ti gobyerno da? because their communities are relatively small and easy to govern They are peace-loving people. council of elders: wields their authority PANGLACAYEN: term used for elders Anya ti itsura da? Anya ti langa da? SUBTRIBES AND THEIR SUBSISTENCE Banaos: made their reputation in agriculture, deriving their livelihood from what the soil yeilds. The Banaos are in municipalities of Daguioman and Malibcong. Masadi-its: nomadic in existence; the kaingeros in the tribe. The Masadi-its are found in Manabo, Bucloc, Sallapadan and Boliney. Maengs: ranchers found in towns of Tubo, San Isidro, Villaviciosa, and Malibcong. Mabacas: game hunters and fishermen. They are found in Lacub and Malibcong. Adasen: found in Dolores, Langilang, Sallapadan and Tineg Balatocs: the Tingguian counterpart of the Tubo tribe of Mindanao wilds for being the skilled craftsmen. Crafts include: carve mortars, grinding stones, cast bolos and similar impalements. Binongans: summate romantics, they are carefree, they are more pre- occupied with their guitars and musical instruments. Other sub-tribes: Adasen: found in Dolores, Langilang, Sallapadan and Tineg Gubangs: found in Malibcong and Tayum. Danak: relatively a small group, they are scattered throughout the province of Abra. Ang KOMUNIDAD The Tinguian are familiar with the Igorot town, made -

Cordillera Administrative Region

` CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION I. REGIONAL OFFICE Room 111 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-2180 Email ADDress: [email protected] Janette S. Padua - Regional Officer-In-Charge (ROIC) Cosme D. Ibis, Jr. - CPPO/Special Assistant to the ROIC Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Kirk John S. Yapyapan - Administrative Officer IV/Acting Accountant Mur Lee C. Quezon - Administrative Officer II/BuDget Officer Redentor R. Ambanloc - Probation anD Parole Officer I/Assistant CMRU Ma. Christina R. Del Rosario - Administrative Officer I Kimberly O. Lopez - Administrative AiDe VI/Acting Property Officer Cleo B. Ballo - Job Order Personnel Aledehl Leslie P. Rivera - Job Order Personnel Ronabelle C. Sanoy - Job Order Personnel Monte Carlo P. Castillo - Job Order Personnel Karl Edrenne M. Rivera - Job Order Personnel II. CITY BAGUIO CITY PAROLE AND PROBATION OFFICE Room 109 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-8660 Email ADDress: [email protected] PERSONNEL COMPLEMENT Daisy Marie S. Villanueva - Chief Probation and Parole Officer Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Mary Ann A. Bunaguen - Senior Probation and Parole Officer Anniebeth B. TriniDad - Probation and Parole Officer II Romuella C. Quezon - Probation and Parole Officer II Maria Grace D. Delos Reyes - Probation and Parole Officer I Josefa V. Bilog - Job Order Personnel Kristopher Picpican - Job Order Personnel AREAS OF JURISDICTION 129 Barangays of Baguio City COURTS SERVED RTC Branches 3 to 7 - Baguio City Branches 59 to 61 - Baguio City MTCC Branches 1 to 4 - Baguio City III. -

Region Penro Cenro Municipality Barangay

AREA IN REGION PENRO CENRO MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT NAME OF ORGANIZATION TYPE OF ORGANIZATION SPECIES COMMODITY COMPONENT YEAR ZONE TENURE WATERSHED SITECODE REMARKS HECTARES CAR Abra Bangued Sallapadan Ududiao Lone District 50.00 UDNAMA Highland Association Inc. PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0001-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Amti Lone District 50.00 Amti Minakaling Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0002-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Danac east Lone District 97.00 Nagsingisinan Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0003-0097 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Danac West Lone District 100.00 Danac Pagrang-ayan Farmers Tree Planters Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0004-0100 CAR Abra Bangued Daguioman Cabaruyan Lone District 50.00 Cabaruyan Daguioman Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0005-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Kilong-olao Lone District 100.00 Kilong-olao Boliney Farmers Association Inc. PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0006-0100 CAR Abra Bangued Sallapadan Bazar Lone District 50.00 Lam aoan Gayaman Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0007-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Bucloc Lingey Lone -

Humanitarian Bulletin Typhoon Yutu Follows in the Destructive Path Of

Humanitarian Bulletin Philippines Issue 10 | November 2018 HIGHLIGHTS In this issue • Typhoon Yutu causes Typhoon Yutu follows Typhoon Mangkhut p.1 flooding and landslides in the northern Philippines, Marawi humanitarian response update p.2 affecting an agricultural ASG Ursula Mueller visit to the Philippines p.3 region still trying to recover Credit: FAO/G. Mortel from the devastating impact of Typhoon Mangkhut six weeks earlier. Typhoon Yutu follows in the destructive path of • As the Government looks to rebuilding Marawi City, there Typhoon Mankhut is a need to provide for the residual humanitarian needs Just a month after Typhoon Mangkhut, the strongest typhoon in the Philippines since of the displaced: food, shelter, Typhoon Haiyan, Typhoon Yutu (locally known as Rosita) entered the Philippine Area of health, water & sanitation, Responsibility (PAR) on 27 October. The typhoon made landfall as a Category-1 storm education and access to on 30 October in Dinapigue, Isabela and traversed northern Luzon in a similar path to social services. Typhoon Mankghut. By the afternoon, the typhoon exited the western seaboard province • In Brief: Assistant Secretary- of La Union in the Ilocos region and left the PAR on 31 October. General for humanitarian Affected communities starting to recover from Typhoon Mangkhut were again evacuated affairs Ursula Mueller visits and disrupted, with Typhoon Yutu causing damage to agricultural crops, houses and the Philippines from 9-11 October, meeting with IDPs schools due to flooding and landslides. In Kalinga province, two elementary schools affected by the Marawi were washed out on 30 October as nearby residents tried to retrieve school equipment conflict and humanitarian and classroom chairs. -

A. Mining Tenement Applications 1

MPSA Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU - CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF JULY 2021 MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) ANNEX-B %Ownership of Major SEQ HOLDER WITHIN PARCEL TEN Filipino and Foreign DATE FILED DATE APPROVED APPRVD (Integer no. of TENEMENT NO (Name, Authorized Representative with AREA (has.) MUNICIPALITY PROVINCE COMMODITY MINERAL REMARKS No. TYPE Person(s) with (mm/dd/yyyy) (mm/dd/yyyy) (T/F) TENEMENT NO) designation, Address, Contact details) RES. (T/F) Nationality A. Mining Tenement Applications 1. Under Process Shipside, Inc., Buguias, Beng.; With MAB - Case with Cordillera Atty. Pablo T. Ayson, Jr., Tinoc, Ifugao; Bauko Benguet & Mt. 49 APSA-0049-CAR APSA 4,131.0000 22-Dec-1994 Gold F F Exploration, Inc. formerly NPI Atty in fact, BA-Lepanto Bldg., & Tadian, Mt. Province (MGB Case No. 013) 8747 Paseo de Roxas, Makati City Province Jaime Paul Panganiban Wrenolph Panaganiban Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 63 APSA-0063-CAR APSA Authorized Representative 85.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver AC 152, East Buyagan, La Trinidad, 127172) Benguet June Prill Brett James Wallace P. Brett, Jr. Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 64 APSA-0064-CAR APSA Authorized Representative. 98.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver #1 Green Mansions Rd. 127172) Mines View Park, B.C. Itogon Suyoc Resoucres, Inc. -

Department of Social Welfare and Development Cordillera Administrative Region Baguio City

Department of Social Welfare and Development Cordillera Administrative Region Baguio City Minutes of the Meeting: Pre-Bid Conference June 6, 2019 Attendance: Concepcion Navales, Alternate,Vice-Chairperson, BAC Eleonor Bugalin-Ayan, End-user Lailani Amora, Technical Expert Leonila G. Lapada, BAC Secretariat Observer: None Prospective Bidder: None Subject: 1. ITB 2019-DSWD-CAR-012: Purchase of Food Supplies for Supplementary Feeding Program in Flora, Luna, Sta. Marcela and Pudtol, Apayao 2. ITB 2019-DSWD-CAR-013: Purchase of Food Supplies for Supplementary Feeding Program in Asipulo, Banaue, Kiangan, Lagawe, Lamut, Tinoc and Aguinaldo, Ifugao 3. ITB 2019-DSWD-CAR-014: Purchase of Food Supplies for the implementation of SupplementaryFeeding Program in Bangued, Boliney, Bucay, Daguioman, Danglas, La Paz, Lacub, Lagayan, Langiden, Licuan- Baay, Luba, Malibcong, Manabo, Penarrubia, Pidigan, Sallapadan, San Isidro, San Quintin and Tubo, Abra under ITB 2019-DSWD-CAR-014 Highlights of the Meeting: A meeting was called to order by Ms. Concepcion Navales, Alternate Vice- Chairperson, Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) in her office at 9:00 AM for the Pre- Bid Conference for the procurement of Food Supplies for the Implementation of Supplementary Feeding Program in Apayao, Ifugao and Abra. There was no prospective bidder attended the activity and none among the invited observers from Jaime Ongpin Foundation, Blessed Association of Retired Persons Foundation, Inc., Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry, DSWD Internal Auditor and COA-CAR attended the said activity. The BAC went on with the meeting upon determination of a quorum and reviewed the bidding documents and technical specifications. The BAC discussed the following: 1 Subject Matter Discussions Agreements Reached/ Recommendations Absence of It was reported that no prospective bidder prospective yet who signified interest to participate in bidder the bidding process. -

2016 Was Indeed a Challenging and Fulfilling Year for the Mines and Geosciences Bureau-Regional Office No

Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU Regional Office No. 1 San Fernando City, La Union REGIONAL PROFILE ASSESSMENT Assessment Physical vis-a-vis Financial Performance Organizational Issues Assessment of Stakeholder’s Responses NARRATIVE REPORT OF ACCOMPLISHMENT General Management and Supervision MINERAL RESOURCE SERVICES Communication Plan for Minerals Development Geosciences and Development Services Geohazard Survey and Assessment Geologic Mapping Groundwater Resource and Vulnerability Assessment Miscellaneous Geological Services MINING REGULATION SERVICES Mineral Lands Administration Mineral Investment Promotion Program Mining Industry Development Program CHALLENGES FOR 2017 PERFORMANCE INFORMATION REPORT PHYSICAL ACCOMPLISHMENT vis-à-vis Prepared by: FUND UTILIZATION REPORT CHRISTINE MAE M. TUNGPALAN Planning Officer II ANNEXES MGB-I Key Officials Directory MGB-I Manpower List of Trainings Attended/Conducted Noted by: Tenement Map CARLOS A. TAYAG OIC, Regional Director REGIONAL PROFILE Region I, otherwise known as the Ilocos Region, is composed of four (4) provinces – Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, La Union and Pangasinan – and nine (9) cities – Laoag, Batac, Candon, Vigan, San Fernando, Dagupan, San Carlos, Alaminos, and Urdaneta. The provinces have a combined number of one hundred twenty five (125) cities and municipalities and three thousand two hundred sixty five (3,265) barangays. Region I is situated in the northwestern part of Luzon with its provinces stretching along the blue waters of West Philippine Sea. Bounded on the North by the Babuyan Islands, on the East by the Cordillera Provinces, on the west by the West Philippine Sea, and on the south by the provinces of Tarlac, Nueva Ecija and Zambales. It falls within 15°00’40” to 18°00’40” North Latitude and 119°00’45” to 120°00’55” East Longitude. -

In the Matter of the Application For

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION Pacific Center Building San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR APROVAL OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PROJECT FOR 2020, NAMELY: PURCHASE AND INSTALLATION OF NEW 10 MVA POWER TRANSFORMER FOR CALABA SUBSTATION ERC CASE NO. 2021-039_______ RC May 27, 2021 ABRA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE (ABRECO), Applicant. x - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x APPLICATION APPLICANT, ABRA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE (ABRECO) thru counsel, unto this Honorable Commission, most respectfully alleges that: THE APPLICANT 1. ABRECO is an electric cooperative duly organized and existing by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with principal office address at Calaba, Bangued, Abra; 2. It holds an exclusive franchise issued by the National Electrification Commission to operate an electric light and power distribution service in the twenty-seven (27) municipalities of the province of Abra, namely: Bangued, Baay-Licuan, Boliney, Bucay, Bucloc, Daguioman, Danglas, Dolores, Lacub, Lagangilang, Lagayan, 1 | P a g e La Paz, Langiden, Luba, Malibcong, Manabo, Peñarrubia, Pidigan, Pilar, Sallapadan, San Isidro, San Juan, San Quintin, Tayum, Tineg, Tubo and Villaviciosa. LEGAL BASES FOR THE APPLICATION 3. Pursuant to Republic Act No. 9136, ERC Resolution 26, Series of 2009 and other laws and rules, and in line with its mandate to provide safe, quality, efficient and reliable electric service to electric consumers in its franchise area, ABRECO submits the instant application for the Honorable Commission’s consideration, permission and approval of its Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) Project for 2020, namely: Purchase and Installation of New 10 MVA Power Transformer for its Calaba Substation located at Brgy.