House of Representatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 2021

Monthly Weather Review Australia February 2021 The Monthly Weather Review - Australia is produced by the Bureau of Meteorology to provide a concise but informative overview of the temperatures, rainfall and significant weather events in Australia for the month. To keep the Monthly Weather Review as timely as possible, much of the information is based on electronic reports. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of these reports, the results can be considered only preliminary until complete quality control procedures have been carried out. Any major discrepancies will be noted in later issues. We are keen to ensure that the Monthly Weather Review is appropriate to its readers' needs. If you have any comments or suggestions, please contact us: Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 Australia [email protected] www.bom.gov.au Units of measurement Except where noted, temperature is given in degrees Celsius (°C), rainfall in millimetres (mm), and wind speed in kilometres per hour (km/h). Observation times and periods Each station in Australia makes its main observation for the day at 9 am local time. At this time, the precipitation over the past 24 hours is determined, and maximum and minimum thermometers are also read and reset. In this publication, the following conventions are used for assigning dates to the observations made: Maximum temperatures are for the 24 hours from 9 am on the date mentioned. They normally occur in the afternoon of that day. Minimum temperatures are for the 24 hours to 9 am on the date mentioned. They normally occur in the early morning of that day. -

Flinders Island Tourism and Business Inc. /Visitflindersisland

Flinders Island Tourism and Business Inc. www.visitflindersisland.com.au /visitflindersisland @visitflindersisland A submission to the Rural & Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee The operation, regulation and funding of air route service delivery to rural, regional and remote communities with particular reference to: Background The Furneaux Islands consist of 52 islands with Cape Barren and Flinders Island being the largest. The local Government resident population at the 2016 census was 906 and rose 16 % between the last two censuses. The Flinders Island Tourism & Business Inc. (FITBI)represents 70 members across retail, tourism, fishing and agriculture. It plays a key role in developing the visitor economy through marketing to potential visitors as well as attracting residents to the island. In 2016, FITBI launched a four-year marketing program. The Flinders Island Airport at Whitemark is the gateway to the island. It has been owned by the Flinders Council since hand over by the Commonwealth Government in the early 1990’s. Being a remote a community the airport is a critical to the island from a social and economic point of view. It’s the key connection to Tasmania (Launceston) and Victoria. The local residents must use air transport be that for health or family reasons. The high cost of the air service impacts on the cost of living as well as discouraging visitors to visit the island. It is particularly hard for low income families. The only access via sea is with the barge, Matthew Flinders 11, operated by Furneaux Freight out of Bridport. This vessel has very basic facilities for passengers and takes 8hours one way. -

Monthly Weather Review Australia January 2021

Monthly Weather Review Australia January 2021 The Monthly Weather Review - Australia is produced by the Bureau of Meteorology to provide a concise but informative overview of the temperatures, rainfall and significant weather events in Australia for the month. To keep the Monthly Weather Review as timely as possible, much of the information is based on electronic reports. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of these reports, the results can be considered only preliminary until complete quality control procedures have been carried out. Any major discrepancies will be noted in later issues. We are keen to ensure that the Monthly Weather Review is appropriate to its readers' needs. If you have any comments or suggestions, please contact us: Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 Australia [email protected] www.bom.gov.au Units of measurement Except where noted, temperature is given in degrees Celsius (°C), rainfall in millimetres (mm), and wind speed in kilometres per hour (km/h). Observation times and periods Each station in Australia makes its main observation for the day at 9 am local time. At this time, the precipitation over the past 24 hours is determined, and maximum and minimum thermometers are also read and reset. In this publication, the following conventions are used for assigning dates to the observations made: Maximum temperatures are for the 24 hours from 9 am on the date mentioned. They normally occur in the afternoon of that day. Minimum temperatures are for the 24 hours to 9 am on the date mentioned. They normally occur in the early morning of that day. -

3Rd Quarterly Report January – March 2017

Annexure 17 - D8 - April 2017 3rd Quarterly Report January – March 2017 1 Annexure 17 - D8 - April 2017 Flinders Council BRANCH QUARTERLY PROGRESS AGAINST OPERATIONAL PLAN (March 16/17) Business Unit Quarterly Progress Report Against Operational Plan Airport Strategic 3 Access and Connectivity - Work with service providers and other relevant stakeholders to improve security, reliability Focus and cost effectiveness. Area: Strategic 3.2 Maintain air access to the Island and improve performance of the airport. Direction: ACTIONS STATUS % COMP PROGRESS COMMENTS RESP. OFFICER START DATE COMP DATE Output: 3.2.1 Improved operation and financial performance of airport. 3.2.1.2 Carry out runway pavement Ongoing 1st Quarter: Council is continuing to carry out the priority pavement repair program as Airport Operations 1/07/2016 30/06/2017 repairs as required. recommended by Simon Oakley from aurecon. Each quarter Simon Oakley conducts a Officer full visual inspection of all pavement areas of the Flinders Island Airport and provides a maintenance plan which Council then carries out. Simon Oakley will carry out his next inspection on the 5th October where he will provide a maintenance plan for the next 3 months. Simon also provides Flinders Council with a letter notifying CASA of the current runway serviceability condition. 2nd Quarter: Simon Oakley carried out his inspection on October and notified CASA that Runway 14/32 is continuing to be actively managed to a safe standard. Council recently went to tender for stabilisation works, Hiway Stabilisers were the successful tenderer and will be on the Island at the end of February/Early March to complete stabilisation works on runway 14/32. -

MINUTES AAA Tasmanian Division Meeting AGM

MINUTES AAA Tasmanian Division Meeting AGM 13 September 2019 0830 – 1630 Hobart Airport Chair: Paul Hodgen Attendees: Tom Griffiths, Airports Plus Samantha Leighton, AAA David Brady, CAVOTEC Jason Rainbird, CASA Jeremy Hochman, Downer Callum Bollard, Downer EDI Works Jim Parsons, Fulton Hogan Matt Cocker, Hobart Airport (Deputy Chair) Paul Hodgen, Launceston Airport (Chair) Deborah Stubbs, ISS Security Michael Cullen, Launceston Airport David McNeil, Securitas Transport Aviation Security Australia Michael Burgener, Smiths Detection Dave Race, Devonport Airport, Tas Ports Brent Mace, Tas Ports Rob Morris, To70 Aviation (Australia) Simon Harrod, Vaisala Apologies: Michael Wells, Burnie Airport Sarah Renner, Hobart Airport Ewan Addison, ISS Security Robert Nedelkovski, ISS Security Jason Ryan, JJ Consulting Marcus Lancaster, Launceston Airport Brian Barnewall, Flinders Island Airport 1 1. Introduction from Chair, Apologies, Minutes & Chairman’s Report: The Chair welcomed guests to the meeting and thanked the Hobart team for hosting the previous evenings dinner and for the use of their boardroom today. Smith’s Detection were acknowledged as the AAA Premium Division Meetings Partner. The Chair detailed the significant activity which had occurred at a state level since the last meeting in February. Input from several airports in the region had been made into the regional airfares Senate Inquiry. Outcomes from the Inquiry were regarded as being more political in nature and less “hard-hitting” than the recent WA Senate Inquiry. Input has been made from several airports in the region into submissions to the Productivity Commission hearing into airport charging arrangements. Tasmanian airports had also engaged in a few industry forums and submissions in respect of the impending security screening enhancements and PLAGs introduction. -

St Helens Aerodrome Assess Report

MCa Airstrip Feasibility Study Break O’ Day Council Municipal Management Plan December 2013 Part A Technical Planning & Facility Upgrade Reference: 233492-001 Project: St Helens Aerodrome Prepared for: Break Technical Planning and Facility Upgrade O’Day Council Report Revision: 1 16 December 2013 Document Control Record Document prepared by: Aurecon Australia Pty Ltd ABN 54 005 139 873 Aurecon Centre Level 8, 850 Collins Street Docklands VIC 3008 PO Box 23061 Docklands VIC 8012 Australia T +61 3 9975 3333 F +61 3 9975 3444 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Report Title Technical Planning and Facility Upgrade Report Document ID 233492-001 Project Number 233492-001 File St Helens Aerodrome Concept Planning and Facility Upgrade Repot Rev File Path 0.docx Client Break O’Day Council Client Contact Rev Date Revision Details/Status Prepared by Author Verifier Approver 0 05 April 2013 Draft S.Oakley S.Oakley M.Glenn M. Glenn 1 16 December 2013 Final S.Oakley S.Oakley M.Glenn M. Glenn Current Revision 1 Approval Author Signature SRO Approver Signature MDG Name S.Oakley Name M. Glenn Technical Director - Title Senior Airport Engineer Title Airports Project 233492-001 | File St Helens Aerodrome Concept Planning and Facility Upgrade Repot Rev 1.docx | -

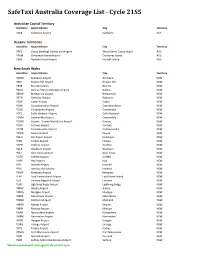

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Northern Integrated Transport Plan

NORTHERN INTEGRATED TRANSPORT PLAN November 2013 questions? Copies of the Plan are also available at: www.dier.tas.gov.au Comments on the Plan should be submitted to: Northern Integrated Transport Plan Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources GPO Box 936 Hobart 7000 or e: [email protected] Your comments are important and we look forward to your input to enable us to deliver a transport system that meets the future need of the Northern Region. contents foreword ................................................................................................2 introduction .........................................................................................3 the northern region ........................................................................5 future transport system ................................................................9 freight ....................................................................................................10 people ..................................................................................................13 land use planning ............................................................................16 environment .....................................................................................18 tourism.................................................................................................20 principles .............................................................................................22 implementation ...............................................................................23 -

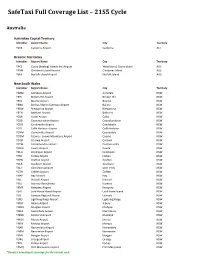

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Program of Activities

CAREC Off-Grid Systems and New Technology Training 21-24 November 2016 Victoria and Tasmania, Australia Program of Activities 20 November 2016 (Sunday) Day 1 Activity Remarks Arrival of CAREC participants Oaks on Collins Hotel Welcome to Australia! 480 Collins St, Melbourne Please see attached documents regarding the logistical arrangements and detailed information regarding this training. (There may be additional information available at the reception desk for delegates at check-in) 7:00 PM-9:00 PM Dinner Venue to be announced CAREC 21 November 2016 (Monday) Day2 Activity Remarks 7:00 AM-8:30 AM Breakfast in Oats on Collins 8:30AM-8:40AM Leave for Tesla Office Assemble in the hotel lobby and leave for Tesla office at 8:40AM sharp. Delegates will leave by rented taxi. 9:00 AM-11:00 AM Electric Vehicles by Tesla Australia Presenter: Mr. Tim McBride Objective: - to understand how electric cars compare with traditional internal combustion engine cars and its charging options from the power grid - the demonstration will include Tesla Power Wall, the Tesla's home battery system Tesla Motors was founded in 2003 by a group of engineers in Silicon Valley who wanted to prove that electric cars could be better than gasoline-powered cars. 11:30AM-12:30PM MoreLunch details at www.tesla.com 12:30PM-3:40PM Energy Sector Coordinating Committee (ESCC) Meeting • ESCC Meeting Agenda • Energy Investment Forum 2 • Proposed Concept Note: RETA on the use of Battery for RE • RETA on Leapfrogging • Work Plan for 2017 • CAREC Strategy for the next five years • ESCC and Climate Change • ESCC Updates Presenter: Mr. -

Supporting Primary Health Care Within Regional Tasmania

Supporting primary health care within regional Tasmania Annual Report 2013/14 TASMANIA CONTENTS > Highlights 4 Message from the National Chair 7 Message from our President 8 Our community 10 Fred Mckay Medical Student Scholarship Report 14 Robin Miller RFDS Nursing Scholarship 16 John Flynn Dental Assistant Scholarship Report 18 Corporate Governance Statement 20 RFDS Tasmania Board 21 Summary Financial Report 22 In Appreciation 23 OUR MISSION > To provide excellence The Royal Flying Doctor Service was in aeromedical and established in Tasmania in 1960, using single primary health care engine aircraft chartered from Tasmanian across Australia aero clubs. Today, in partnership with Ambulance Tasmania, the RFDS operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and provides Tasmanians with services which include emergency trauma evacuations and inter- hospital transfers to take patients to the special care they need. COVER: JORDAN DE HOOG, INAUGURAL ROBIN MILLER RFDS NURSING SCHOLARSHIP RECIPIENT. 2 ROYAL FLYING DOCTOR SERVICE | TASMANIA 2013/14 ANNUAL REPORT 3 THE YEAR’S HIGHLIGHTS > RFDS Tasmania Primary Health Initiative being developed 2013/14 Dental scholarshp awarded to Sam Simpson Preparations are Medical Scholarship Inter-hospital transfers Robin Miller RFDS Nursing underway for the awarded to Scholarship awarded to construction of two patient transfer 1025 facilities at King and Cate Jordan Flinders Islands Kube de Hoog 2 Dental patients treated RFDS Tasmania Flown around Tasmania and Interstate on Flinders Island continues support of the Menzies Institute 271 ASPREE Study 440, 754 km 4 ROYAL FLYING DOCTOR SERVICE | TASMANIA 2013/14 ANNUAL REPORT 5 MESSAGE FROM THE NATIONAL CHAIR The RFDS is the most iconic Australian used to provide regional airports around not-for-profit organisation. -

MINUTES TAS Division Meeting

MINUTES TAS Division Meeting Date: Thursday 25 June 2015 Time: 9.00am – 1.00pm Location: Launceston Airport Boardroom Attendees: Mel Percival Hobart Airport Matt Cocker Hobart Airport Michael Cullen Launceston Airport Peter Holmes Launceston Airport Michael Wells Burnie Wynyard Airport Geoff Grace Flinders Island Airport Peter Friel Devonport Airport Jared Feehely AAA Geoff Dugan Tas Ports Ross Loakim Downer Tom Griffiths Airports Plus Pty Ltd Rod Sullivan Burnie Wynyard Airport Apologies: Paul Hodgen Launceston Airport Rod Parry Hobart Airport Kent Quigley AirServices Australia Caroline Wilkie AAA Arthur Johnson King Island Airport 1. Welcome and Introductions Mel Percival, Chair of AAA Tas Division opened the meeting and thanked members for attendance. The minutes from the joint TAS/VIC meeting were tabled and noted by members. 2. AAA National Update Jared Feehely, AAA Regional Airports Officer, provided members with a summary of major initiatives undertaken in 2014/15 by the AAA and also outlined the focus areas for 2015/16. This summary included: 60 major milestones being identified for 2015/16 with a particular focus on education delivery (including the appointment of education manager in AAA) and a strong focus on security/CASA and compliance. Major initiatives delivered include Ops Swap, Airport Safety Week, MOS 139 Post Implementation Review and delivering a new AAA website Policy focus areas for the year have focused on lobbying a ‘risk based approach’ to security, in addition to work on planning, deregulation and aerodrome safety. Information on a senate enquiry into aviation security is expected soon, unsure of the outcome The Chair moved to congratulate the AAA on their achievements in 2015 and the focus areas being targeted, and also provided an overview of the work being completed on an all of state access strategy for Tasmania, which is seeking to deliver a coordinated access plan and strategy.