Calgary, Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article: Delcosecurity Featured in Itbusiness

6 TECHNOLOGYin GOVERNMENT News December 2003 CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES ...~ '" ~ Iu ~ 0 , if] ii..0 ..~ EdmontonInstitutionupdatesprison SKI!)!I doorcontrolsystemwithtouchscreens Overhaulispartof anITupgradethat will replacecurrentpush-locksystem BY NEIL SUTTON is replacing "a console that's safe environment for both staff anada's prison system is un- probably eight feet long and five and offenders," said Tim Krause, dergoing an IT upgrade feet deep that wraps around and regional prairie region commu- Cwhereby certain institutions takes up most of the control cen- nications manager for the Cor- are replacing push-button lock- tre room. It's full of switches rectional Service of Canada. ing systems with touch-screen (and) LEDs," he said. By com- "The biggest thing would be technology to im- parison, the Delco ease of operation for the security prove security. technology is "a staff that are going to be operat- The most recent smaller console ing all the different locking addition is the with a flat panel mechanisms," he added. "This is Delco Automation's touch-screen technology keeps Edmonton Institution inmates behind bars. Edmonton Insti- monitor with a part of a standard operations and tution, a maxi- few other systems maintenance program that we're Stony Mountain Institution in Legimodiere. mum security mounted on the seeing in the prairie region that Manitoba. Julia Noonan, a spokesperson prison which console. " updates various systems to the Other facilities across the with the Ontario Ministry of houses more than In the event of a modern-day technology." country are receiving the same Public Safety and Security, says 300 inmates. It's power failure, the Edmonton Institution inmates treatment. -

A Message from the President …

Share Enjoy Enrich Newsletter of the Faculty Women’s Club, University of Alberta Vol. 32, No. 1 August 2018 A message from the President … Summer greetings to you all. I hope you are enjoying these summer days here in Edmonton or wherever your travels have taken you. I wish to extend a hearty welcome to all new and returning members of the Faculty Women's Club. I hope to see you at our annual Wine and Cheese Registration Event on September 18 at the Faculty Club. The gathering will launch our eighty-fifth year, and is always a wonderful time to meet new people and to catch up with old friends, as well as to see what our interest groups have planned for the coming year. A special thanks to the Program Committee for their hard work and dedication in planning this first event of the year. Our Executive Committee works very hard to help the FWC run smoothly. I'm excited to introduce this outstanding team to you: Past-President, Jan Heaman, continues to share her experience and wisdom in the leadership of FWC. Lucie Moussu, our new Vice-President, will be co-ordinating the various interest groups, which are the heart of the FWC. Linda Seale has accepted the role of Secretary and will be maintaining and distributing minutes for our Executive meetings. Our new Treasurer, Sandra Wiebe, will monitor our organization's finances and maintain our records. Marie Dafoe is in charge of memberships - registration, renewal, and fee payment. Tricia Unsworth has stepped up to maintain our directory, which has been maintained by Joan Hube for many years. -

Designated Airspace Handbook

TP 1820E DESIGNATED AIRSPACE HANDBOOK (Aussi disponible en français) PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MINISTER OF TRANSPORT ISSUE NO 280 EFFECTIVE 0901Z 30 JANUARY 2020 (Next Issue: 26 MARCH 2020) CAUTION THE INFORMATION IN THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE SUPERSEDED BY NOTAM SOURCE OF CANADIAN CIVIL AERONAUTICAL DATA: NAV CANADA SOURCE OF CANADIAN MILITARY AERONAUTICAL DATA: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL DEFENCE PRODUCED BY DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL DEFENCE PUBLISHED BY NAV CANADA TRANSPORT CANADA DESIGNATED AIRSPACE HANDBOOK Table of Contents Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.) General...............................................................................................................................................................................2 1.1) Standards........................................................................................................................................................2 1.2) Abbreviations & Acronyms..............................................................................................................................3 1.3) Glossary of Aeronautical Terms and Designations of Miscellaneous Airspace ..............................................4 2.) Navigation Aid and Intersection/Fix Coordinates Used to Designate Airspace .......................................................15 2.1) Navigation -

Kiyâm MINGLING VOICES Series Editor: Manijeh Mannani

kiyâm MINGLING VOICES Series editor: Manijeh Mannani Give us wholeness, for we are broken. But who are we asking, and why do we ask? — PHYLLIS WEBB Mingling Voices draws on the work Poems for a Small Park of both new and established poets, E.D. Blodgett novelists, and writers of short stories. Dreamwork The series especially, but not exclusively, Jonathan Locke Hart aims to promote authors who challenge Windfall Apples: Tanka and Kyoka traditions and cultural stereotypes. It Richard Stevenson is designed to reach a wide variety of readers, both generalists and specialists. The dust of just beginning Mingling Voices is also open to literary Don Kerr works that delineate the immigrant Roy & Me: This Is Not a Memoir experience in Canada. Maurice Yacowar Zeus and the Giant Iced Tea Leopold McGinnis Musing Jonathan Locke Hart Praha E.D. Blodgett Dustship Glory Andreas Schroeder The Kindness Colder Than the Elements Charles Noble The Metabolism of Desire: The Poetry of Guido Cavalcanti Translated by David R. Slavitt kiyâm Naomi McIlwraith poems by Naomi McIlwraith Copyright © 2012 Naomi McIlwraith Second printing 2012 Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 ISBN 978-1-926836-69-0 (print) 978-1-926836-70-6 (PDF) 978-1-926836-71-3 (epub) A volume in Mingling Voices ISSN 1917-9405 (print) 1917-9413 (online) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printers. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication McIlwraith, Naomi L. Kiyâm : poems / by Naomi McIlwraith. (Mingling voices, ISSN 1917-9405) Issued also in electronic formats. -

Youth Pathways in Articulated Postsecondary Systems: Enrolment and Completion Patterns of Urban Young Women and Men*

The Canadian Journal of Higher Education La revue canadienne d'enseignement supérieur Volume XXIX, No. 1,1999 pages 47-46 Youth Pathways in Articulated Postsecondary Systems: Enrolment and Completion Patterns of Urban Young Women and Men* LESLEY ANDRES & HARVEY KRAHN The University of British Columbia & University of Alberta ABSTRACT This paper uses panel survey data to document the postsecondary educational activity of high school graduates in Edmonton and Vancouver over a five-year period. It enquires whether, in "articulated" postsec- ondary systems offering a range of institutional choices and a variety of transfer options, large class and gender differences in participation and completion continue to be observed. The results reveal that even in sys- tems explicitly designed to improve access to and encourage completion of postsecondary programs, family background continues to strongly influence postsecondary outcomes. In both cities, social class advantages appear to be passed from one generation to the next, to a large extent, through the high school tracking system, since high school academic pro- gram is a strong predictor of postsecondary participation and completion. Gender also continues to matter, but in more subtle ways than in the past. * The authors would like to thank several anonymous reviewers for this journal for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We wish to acknowledge the sup- port received from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada in the form of a strategic research grant in the theme area of Education and Work in a Changing Society. The grant has enabled the co-investigators to develop a collabora- tive network in order to compare and contrast their longitudinal data sets. -

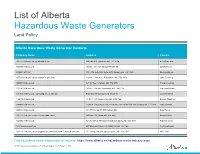

List of Hazardous Waste Generators

List of Alberta Hazardous Waste Generators Land Policy Alberta Hazardous Waste Generator Contacts Company Name Address Contact 1037128 Alberta Ltd o/a Alberta Hotel PO Box 430 Vegreville AB T9C 1R4 Kun Whan Kim 1038900 Alberta Ltd 10945 - 101 AVE Grande Prairie AB Ed McKenzie 1049601 BC Ltd 350 - 7th AVE SW, Suite 2800 Calgary AB T2P 3N9 Michael Baleja 1057974 Alberta Ltd o/a Global Dewatering 16813 - 128A Ave Edmonton AB T5V 1K9 John Devaney 1065579 Alberta Ltd. 42148 Hwy 1 Calgary AB T3Z 2P2 Fiona Kreschuk 1111041 Alberta Ltd. 14325 - 114 AVE Edmonton AB T5M 2Y8 Carmello Mirante 1131895 Alberta Ltd - operating as J.C. Metals P.O. Box 58 Dunmore AB T0J 1A0 Jennifer Millen 1142386 Alberta Ltd. 11404 143 ST Edmonton AB T5M 1V6 Bernie Westover 1148447 Alberta Ltd. c/o MDC Property Services Ltd 200, 1029 17th AVE SW Calgary AB T2T 0A9 Gary Dundas 1204612 Alberta Ltd. #3 - 5504 - 1A ST SW Calgary AB Kulu Punia 1207201 Alberta Limited (Crossroads Esso) PO Box 509 Viking AB T0B 4N0 Kimook Shin 1228002 Alberta Ltd. 72130 R.P.O. Glenmore Landing Calgary AB T2V 5H9 Robert Hoang 1-2-3 Development Inc. 207 Atkinson Lane Fort McMurray AB T9J 1E8 Scott Tenhuser 1237776 Alberta Ltd o/a Dragons Breath Production Testing & Hot Shot 51112 Rge Rd 270 Spruce Grove AB T7Y 1G7 Mike Hall Find hazardous waste information for industry: https://www.alberta.ca/hazardous-waste-industry.aspx ©2018 Government of Alberta | Published: August 2018 | Page 1 of 178 Alberta Hazardous Waste Generator Contacts Company Name Address Contact 1240796 Alberta Ltd. -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report A community that supports, respects and empowers all women and girls Table of Contents 4 Who was Elizabeth Fry? 5 Message from the President and Executive Director 8 Board of Directors 12 Financial Statements 2019 15 Bridging New Journeys Program Annual Report 2019 18 Edmonton Attendance Center Addictions Program Annual Report 2019 20 Centre 170 - Video Visitation Centre Annual Report 2019 22 Women’s Empowerment Project (WEP) Annual Report 2019 25 Edmonton Remand Centre Rehabilitative Programs Annual Report 2019 27 Housing Support Program Annual Report 2019 30 Girls Empowered and Strong Annual Report 2019 32 Community Resources Program Annual Report 2019 35 Independent Legal Advice for Survivors of Sexual Violence Program Report 2019 37 Indigenous Women’s Program Annual Report 2019 39 Record Suspension Program Annual Report 2019 41 Stoplifting Program Annual Report 2019 43 Financial Literacy Program Annual Report 2019 45 The Work4Women Program Annual Report 2019 47 Provincial Prison Liaison Program Annual Report 2019 50 Courts Programs Annual Report 2019 55 Volunteer Program Annual Report 2019 Vision: A community that supports, respects and empowers all women and girls. Mission: The Elizabeth Fry Society of Edmonton advances the dignity and worth of all women and girls who are, or may be at risk of becoming criminalized. We value and believe... We believe that knowledge building and advocacy are necessary to overcome systemic injustices that impact women and girls. We believe that every person should be accepted and respected for their unique story and culture. We believe that all women and girls deserve non-judgmental support, when experiencing adversity. -

Horse Hill Area Structure Plan

HORSE HILL AREA STRUCTURE PLAN Office Consolidation February 2018 Prepared by: Current Planning Branch Sustainable Development Department City of Edmonton Bylaw 16353, as amended, was adopted by Council in May 2013. In February 2018, this document was consolidated by virtue of the incorporation of the following bylaws, which were amendments to the original bylaw. Bylaw 16353 Approved May 22, 2013 (to adopt the Horse Hill Area Structure Plan) Bylaw 17021 Approved April 28, 2015 (to update maps and statistics based upon the approved Neighbourhood Structure Plan for Neighbourhood #2) Bylaw 18197 Approved February 13, 2018 (to update the maps and statistics to reflect the associated NSP amendment for the area comprising of the Marquis Town Centre) Editor’s Note: This is an office consolidation edition for the Horse Hill ASP, Bylaw 16353, as approved by City Council on May 22, 2013. This edition contains all amendments and additions to Bylaw 16353. For the sake of clarity, new maps and a standardized format were utilized in this Plan. All names of City departments have been standardized to reflect their present titles. Private owner’s names have been removed in accordance with the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. All text changes are noted in the right margin and are italicized where applicable. Furthermore, all reasonable attempts were made to accurately reflect the original Bylaws. This office consolidation is intended for convenience only. In case of uncertainty, the reader is advised to consult the original Bylaws, available at the office of the City Clerk. City of Edmonton Sustainable Development Department Horse Hill Area Structure Plan Office Consolidation ‐ i ‐ HORSE HILL AREA STRUCTURE PLAN Prepared for: Private Developers* Prepared by: * Amended by Editor Horse Hill Area Structure Plan Office Consolidation ‐ ii ‐ CONTENTS *AMENDED BY EDITOR 1 Administration ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Report to the Community

2012 Report to the Community “There’s a certain bond that people establish when they focus their efforts on a common goal. Together, we focused on the goal of helping change lives – through education, income and wellness. We invested in people, helping lift our most vulnerable from poverty.” Dave Mowat • 2012 campaign chair Table of Contents 4 Message from the President & CEO and Chair of the Board 9 Focus Areas: Highlights of 2012–2013 22 A Community Engaged 24 Special Recognition 28 Days of Caring Participation 32 Awards of Distinction 34 Contributors 46 Leading the Way A MESSAGE FROM THE Community Awareness The need in our community is growing and United Ways worldwide have been broadly the cost of delivering services is substantial. Chair of the known for workplace fundraising efforts – In the province of Alberta, poverty costs Board and generating resources and allocating to social between $7.1 billion and $9.5 billion per year sector agencies. But over the past several – this is a monetary cost incurred by us all. In President & CEO years, we have seen a transition from this the Capital Region alone, there are 120,000 model of funder to collaborator – one that people living in poverty – and 37,000 of them What a difference we make when sees participation with partners across all are children. As one of the most prosperous we choose to make a contribution sectors. In the Alberta Capital Region, we regions in North America, it begs the to our community. We’re pleased to have our sights set on lifting people out of question, is it acceptable that anyone should share, through our 2012-13 Report poverty. -

Cafa Distinguished Academic Awards, 2019

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SEPTEMBER 9, 2019 CAFA DISTINGUISHED ACADEMIC AWARDS, 2019 (EDMONTON) – The Confederation of Alberta Faculty Associations (CAFA), the provincial organization representing academic staff associations at the University of Alberta, the University of Lethbridge, Mount Royal University, Grant MacEwan University and Athabasca University, is pleased to announce the recipients of the CAFA Distinguished Academic Awards for 2019. The CAFA Distinguished Academic Awards recognize academic staff members at Alberta’s research and undergraduate universities, who through their research and/or other scholarly, creative or professional activities have made an outstanding contribution to the wider community beyond the university. The recipient of the 2019 CAFA Distinguished Academic Award is Dr. Geoffrey Messier, Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Calgary, in recognition of both his influential research in the field of wireless and digital communication network and his committed to humanitarian contribution to serve people living with homelessness in Calgary and Alberta more broadly. Dr. Tracy Bear, Assistant Professor in the Department of Native Studies, University of Alberta, has been chosen to receive the 2019 CAFA Distinguished Academic Early Career Award for her innovative, interdisciplinary research and artistic practices in the fields of decolonialized sexuality and indigenous feminism. “The annual CAFA Distinguished Academic Awards for over ten years have celebrated the contributions of our members to the community beyond the academy through their research, scholarly and creative pursuits” notes Dr. Heather Bruce, President of CAFA. “On behalf of CAFA, I extend warmest congratulations to Dr. Geoffrey Messier and Dr. Tracy Bear, deserving recipients of our awards for 2019.” The 2019 CAFA Distinguished Academic Awards will be presented at a banquet at the Edmonton Convention Centre in Edmonton, on Thursday, September 12, 2019. -

Annual Report 2019

STAYANNUAL REPORT 2019 Edmonton Public Library 7 Sir Winston Churchill Square NW Edmonton, AB T5J 2V4 CURIOUS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Edmonton Public Library 1 2019 Board Of Trustees MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD CHAIR Dr. Fern Snart, Chair AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Mrs. Kenna Houncaren, Vice Chair The year 2019 has been transformative for the Edmonton Public Library (EPL) as we continue to innovate, collaborate and evolve—reimagining Mr. James Crossman the modern library to best serve the growing and changing needs of Edmontonians. It was the start of EPL’s 2019-2023 Strategic Plan, a five- Dr. Brian Heidecker year blueprint to help EPL be the best place in Edmonton to learn, create, Councillor Ben Henderson be and work. Ms. Jennifer Huntley We delivered exceptional customer experiences through our classes and events and increased our focus on early and digital literacy. As a new Ms. Sandra Marin approach to our adult services, we launched Life Skills classes—a series dedicated to developing specific characteristics and capabilities that Mrs. Zainul Mawji enhance Edmontonians’ chances of success and well-being in life. As one of the first pilot partners in Google’s IT Certificate Program, we helped over 40 Ms. Aaida Peerani students graduate from the program and saw the first student in the program across Canada land an IT job. Ms. Jill Scheyk We increased our memberships by 6% thanks in large part to partnerships with organizations like Northlands who offered Edmontonians free access to K-Days and FarmFair International. In addition, we launched a new website, refreshed our branches with new furniture and equipment, expanded our early literacy program, Welcome Baby, to the Stollery Children’s Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), and became the first public library in North America to create a vinyl album, Riversides, which garnered us an Urban Libraries Council Honourable Mention. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Sandra M. Bucerius Henry Marshall Tory Chair Professor of Sociology and Criminology (As of July 2021) Phone: 1

CURRICULUM VITAE Sandra M. Bucerius Henry Marshall Tory Chair Professor of Sociology and Criminology (as of July 2021) phone: 1-780-709-7954 Director Centre for Criminological Research [email protected] Department of Sociology University of Alberta https://www.ualberta.ca/arts/about/people-collection/sandra-bucerius German citizen; Canadian permanent resident Education 2009 Ph.D., summa cum laude, University of Frankfurt; “The Relationship between Migration, Social Exclusion, and Informal Economies – an Ethnographic Study with Young Migrants” ● 2nd place Deutscher Studienpreis, Koerberstiftung, highest national award for social science dissertations ● Funded by the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes (German National Academic Foundation – funds the top 0.5% of the German student population) and the Frankfurt Graduate School of Social Sciences and Humanities. Current position Since September 2020 Henry Marshall Tory Chair, UAlberta Since July 2020 - Director, Centre for Criminological Research, Department of Sociology, UAlberta Since July 2016 Associate Professor of Sociology and Criminology, Department of Sociology, UAlberta Current key roles Since 2019 Oxford University Handbook Series Editor for Criminology Since 2016 Director of the University of Alberta Prison Project (UAPP) Previous positions 2016 – 2021 Associate Professor of Sociology and Criminology, Department of Sociology, UAlberta 2013 – 2016 Assistant Professor of Sociology and Criminology, Department of Sociology, UAlberta, tenure track 2009 – 2013 Assistant Professor