Rhino Global Cautive Action Plan Propagation Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext

Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. 373 STATE CITY INSTITUTION RECIPROCITY Canada Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Quebec - Granby Granby Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Winnipeg Assiniboine Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% Off Admission Tickets Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Alaska Seward Alaska Sealife Center 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Off Admission Tickets California Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Mateo CuriOdyssey 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets California Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. -

Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Peninsular Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

IN-SITU CONSERVATION OF THE SUMATRAN RHINOCEROS (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) A MALAYSLAN EXPERIENCE Mohd. Khan Momin Khan Burhanuddin Hj. Mohd. Nor Ebil Yusof Mustafa Abdul Rahman Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Peninsular Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. INTRODUCTION The Sumatran rhino is considered to be one of the most endangered wildlife species in Peninsular Malaysia. Surveys conducted throughout the peninsula in 1987 estimated that the population stands at more than 100 animals with most of the population inhabiting the forest of Taman Negara, Endau Rompin and the forest between Gunung Inas and Ulu Selama in Perak. The population in these three locations are considered viable for long- term genetic management. The remainder of the population suwives in the forest reserves and state land throughout the peninsula (Map 1, Table 1). The Sumatran rhinoceros population in the wild is found in mountain ranges and forest of higher elevations in Peninsular Malaysia. This should provide a consolation in terms of the animals' protection, as these forests are seldom logged because they play an important part in water catchment and ithe prevention of soil erosion. Nevertheless, steps should be taken to ensure the survival of these animals, as deforestation is rapidly approaching these areas. Poaching activities increase with the demand for rhino products. The popular beliefs of the horn's medicinal property, especially as an aphrodisiac, escalates the demand for rhino products. This, coupled with the high price of horns, prompts illegal hunters to hunt down these animals. The risks of selling illegal rhino products is high, especially in Kuala Lumpur, thus contributing to the high price of the products. -

2006 Reciprocal List

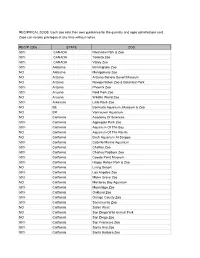

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits List created by © birdsandbats on www.zoochat.com. Last Updated: 19/08/2019 African Clawless Otter (2 holders) Metro Richmond Zoo San Diego Zoo American Badger (34 holders) Alameda Park Zoo Amarillo Zoo America's Teaching Zoo Bear Den Zoo Big Bear Alpine Zoo Boulder Ridge Wild Animal Park British Columbia Wildlife Park California Living Museum DeYoung Family Zoo GarLyn Zoo Great Vancouver Zoo Henry Vilas Zoo High Desert Museum Hutchinson Zoo 1 Los Angeles Zoo & Botanical Gardens Northeastern Wisconsin Zoo & Adventure Park MacKensie Center Maryland Zoo in Baltimore Milwaukee County Zoo Niabi Zoo Northwest Trek Wildlife Park Pocatello Zoo Safari Niagara Saskatoon Forestry Farm and Zoo Shalom Wildlife Zoo Space Farms Zoo & Museum Special Memories Zoo The Living Desert Zoo & Gardens Timbavati Wildlife Park Turtle Bay Exploration Park Wildlife World Zoo & Aquarium Zollman Zoo American Marten (3 holders) Ecomuseum Zoo Salomonier Nature Park (atrata) ZooAmerica (2.1) 2 American Mink (10 holders) Bay Beach Wildlife Sanctuary Bear Den Zoo Georgia Sea Turtle Center Parc Safari San Antonio Zoo Sanders County Wildlife Conservation Center Shalom Wildlife Zoo Wild Wonders Wildlife Park Zoo in Forest Park and Education Center Zoo Montana Asian Small-clawed Otter (38 holders) Audubon Zoo Bright's Zoo Bronx Zoo Brookfield Zoo Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Dallas Zoo Denver Zoo Disney's Animal Kingdom Greensboro Science Center Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens 3 Kansas City Zoo Houston Zoo Indianapolis -

Additional Member Benefits Reciprocity

Additional Member Benefits Columbus Member Advantage Offer Ends: December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted As a Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Member, you can now enjoy you can now enjoy Buy One, Get One Free admission to select Columbus museums and attractions through the Columbus Member Advantage program. No coupon is necessary. Simply show your valid Columbus Zoo Membership card each time you visit! Columbus Member Advantage partners for 2016 include: Columbus Museum of Art COSI Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens (Valid August 1 - October 31, 2016) King Arts Complex Ohio History Center & Ohio Village Wexner Center for the Arts Important Terms & Restrictions: Receive up to two free general admissions of equal or lesser value per visit when purchasing two regular-priced general admission tickets. Tickets must be purchased from the admissions area of the facility you are visiting. Cannot be combined with other discounts or offers. Not valid on prior purchases. No rain checks or refunds. Some restrictions may apply. Offer expires December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted. Nationwide Insurance As a Zoo member, you can save on your auto insurance with a special member-only discount from Nationwide. Find out how much you can save today by clicking here. Reciprocity Columbus Zoo Members Columbus Zoo members receive discounted admission to the AZA accredited Zoos in the list below. Columbus Zoo members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains their own discount policies, and the Columbus Zoo strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 hello stimulate learning, by inspiring and engagingRhinos, cheetahs and okapi, and the places they live in diverse audiences acting locally while thinking globally the world, are facing serious threats — often suffering at 4 foster teamworkthe hand of humans. A year is simply notthrough enough time to effective communication, integration, and collaboration completely turn the tide to ensure their safe future, but I am proud to say that in 2017 theencourage White Oak team has once again our community through positive experience in a caring, welcoming environment stepped up to the challenge. practice responsible stewardship of the natural world with respect for our From the expansion of our property to more than 16,000 acres to doubling summer camp capacity and protecting greater numbers of endangered wildlife, our work in 2017 reflects our commitment to the mission of White Oak: strive for consistent excellence with passion, workplace pridesaving endangered and wildlife and habitats through sustainable commitattention to effective leadership to motivate and empower stakeholders to detail conservation breeding, education and land stewardship. practice responsible stewardship of the natural saving species for future generations Throughout 2017, the White Oak team has showcased our commitment. We believe that every member of the White Oak Team,foster whether working in wildlife, hospitality,teamwork through effective communication, integration, and collaboration education, maintenance, or administration, can impact 18 conservation. This core belief extends beyond White Oak, as encourage our community through positive10 experience in a caring, welcoming environment we believe that every individual, regardless of age, career, or interests can make daily decisions to help protect wildlife commit to effective connectingpractice people to responsible conservation stewardship of the natural world with respect for our and wild places. -

JUNIOR CATEGORY FIRST PRIZE Ariscca Michael Sekolah

JUNIOR CATEGORY FIRST PRIZE Ariscca Michael Sekolah Menengah Sains Seri Puteri, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia TOPIC 1 Write about your favourite primate and say where it is found, and why you like it. My favourite channel has always been Animal Planet since I was a young girl. I could watch a show about orangutans for hours just imagining what the world would have been like without these primates. I’ve always found the behavior of orangutans fascinating yet similar to us humans. Ethology has always been something I’ve wanted to study. It intrigues me how orangutans have personalities, minds and feelings so similar to humans. Jane Goodall, who is a primatologist, shared the same thoughts when she first started her research about primates. One of the other reasons why I love these furry and loving mammals is because of their odd yet warm hands that look like humans’. I still clearly remember the day when my family and I visited the Malacca Zoo. We stayed back to watch the animal show in the evening and we were lucky to get the experience to meet and greet one of the famous orangutans there. Her name was Diana and she could give the best hugs ever. I will never forget that sweet moment when she held my hand. The feeling of her hand was beyond my expectations. At the innocent age of six, I never expected the hands of an orangutan to be warm, smooth and very ladylike. I can still remember crying and not wanting to let go of her warm grasp but I was forced to leave anyway. -

The Husbandry and Veterinary Care of Captive Sumatran Rhinoceros at Zoo Melaka, Malaysia

.klalayan Nature Journal 1990 44: 1-1 9 The Husbandry and Veterinary Care of Captive Sumatran Rhinoceros at Zoo Melaka, Malaysia Abstract: The husbandry, adaptation to captivity, nutrition, biological data and medical problems of the rare and endangered Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) at Zoo Melaka, Peninsular hfalaysia, are described. The clinical management focuses on p problems of the captive Sumatran rhinoceros in this region:Currently, 42% of the world's captive Sumatran rhinoceros populations is located in Zoo Melaka. A female Sumatran rhinoceros, suspected pregnant prior to her capture, gave birth after 469 days in captivity at Zoo hlelaka. The average daily weight gain of the rhinoceros calf was 0.86 kg for the first 12 months. Problems of the skin, adnexa, sensory organs, genitalia, and digestive system are common in the captive Sumatran rhinoceros. A severe necrotizing enteritis suggestive of Salrnonellosis (Salmonella blockley) claimed a female Sumatran rhinoceros. The first mating of captive Sumatran rhinoceros was observed in 1987. However. intro- mission was unsuccessful due to a chronic and severe foot problem in the male. The Sumatran rhinoceros, Dicerortzinus sumatrensis, is the smallest of the five living rhinoceros and one of the most rare and endangered species or large mammals in the world. The Sumatran rhinoceros population oncc estended from thc hilly tracts of Assam on the Eastern borders of India to Burma, Thailand. Indochina, I'eninsular Malaysia. Sumatra and Borneo. Now the species is confined to a fcw island habitats in Thailand, Peninsular hlalaysia, Borneo and Sumatra. Little is known of its status in Burma which P holds the subspecies D. -

FOI Summary, Thianil (Thiafentanil Oxalate), MIF 900-000

Date of Index Listing: June 16, 2016 FREEDOM OF INFORMATION SUMMARY ORIGINAL REQUEST FOR ADDITION TO THE INDEX OF LEGALLY MARKETED UNAPPROVED NEW ANIMAL DRUGS FOR MINOR SPECIES MIF 900-000 THIANIL (thiafentanil oxalate) Captive non-food-producing minor species hoof stock “For immobilization of captive minor species hoof stock excluding any member of a food- producing minor species such as deer, elk, or bison and any minor species animal that may become eligible for consumption by humans or food-producing animals.” Requested by: Wildlife Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Freedom of Information Summary MIF 900-000 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. GENERAL INFORMATION: ............................................................................. 1 II. EFFECTIVENESS AND TARGET ANIMAL SAFETY: .............................................. 1 A. Findings of the Qualified Expert Panel: ...................................................... 2 B. Literature Considered by the Qualified Expert Panel: ................................... 4 III. USER SAFETY: ............................................................................................. 6 IV. AGENCY CONCLUSIONS: .............................................................................. 7 A. Determination of Eligibility for Indexing: .................................................... 7 B. Qualified Expert Panel: ............................................................................ 7 C. Marketing Status: ................................................................................... 7 D. Exclusivity: -

Cop15 Inf. 22 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

CoP15 Inf. 22 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Doha (Qatar), 13-25 March 2010 A STUDY OF PROGRESS ON CONSERVATION OF AND TRADE IN CITES-LISTED TORTOISES AND FRESHWATER TURTLES IN ASIA This document has been submitted by the Secretariat at the request of IUCN/SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group * as an update to Annex 2 of CoP15 Doc 49. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP15 Inf. 22 – p. 1 Implementation of Decision 14.128 A study of progress on conservation of and trade in CITES-listed tortoises and freshwater turtles in Asia This report has been prepared by the IUCN/SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group as an update to Annex 2 of CoP15 Doc 49. Submission of this report fulfills the direction of the Conference of the Parties under Decision 14.128. Background Worldwide some 313 species of tortoises and freshwater turtles inhabit tropical, subtropical and some temperate regions, of which about 90 inhabit Asia (Fritz & Havas, 2007). The IUCN Red List records 128 non-marine turtle species as threatened, placing tortoises and freshwater turtles among the most threatened groups of vertebrates. -

Issue 23.Indd

Issue 23 • February 2, 2010 Copyright 2008 - An IN FOCUS...4 YOU Publication FREE COPY N FOCUS ...4 YOU FOR YOUR READING PLEASURE Administration and Advertising P.O. Box 2 Mee Chok Plaza #4 Chiangmai, Thailand 50300 Email: [email protected] Website: www.infocus4.com The Power of Positive Thinking 18/1 Vieng-kaew Road Tambon Sriphoom Amphur Muang Chiang Mai 50200 by Remez Sasson ositive thinking is a mental attitude that admits into the mind thoughts, words and images that Pare conductive to growth, expansion and success.ss. It 4 is a mental attitude that expects good and favorable results. A ContentsTO YOUR GOOD HEALTH positive mind anticipates happiness, joy, health and a success- ful outcome of every situation and action. Whatever the mind 5 DID YOU expects, it fi nds. KNOW... 7 Not everyone accepts or believes in positive thinking. Some 6 consider the subject as just nonsense, and others scoff at people who believe and accept it. Among the people who accept it, not TIPSTIPS many know how to use it effectively to get results. Yet, it seems that many are becoming YOU CAN USE attracted to this subject, as evidenced by the many books, lectures and courses about it. 8 TECHNOBYTES This is a subject that is gaining popularity. PUBLIC AND MORE INFORMATION 11 It is quite common to hear people say: “Think positive!”, to someone who feels down and CHIANG MAI 121 worried. Most people do not take these words seriously, as they do not know what they HAPPENINGS really mean, or do not consider them as useful and effective. -

Publications of Veterinary Staff White Oak Conservation

Publications of Veterinary Staff White Oak Conservation Stover J, Jacobson ER, Lukas J, Lappin MR, and Buergelt CD : Toxoplasma Gondii in a collection of nondomestic ruminants, JZWM, 21(3):295-301, 1990. Citino SB : Chronic, intermittent Clostridium perfringens enterotoxicosis in a group of cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus), JZWM, 26(2) : 279-285, 1995. Citino SB : Diagnosis of Clostridium perfringens Enterotoxicosis in a Collection of Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus), Proc. American Association of Zoo Veterinarians, 1994, pp. 347-349. Young LE, Hopkins, A, Citino, SB, Papendick, R, and BL Homer : Eastern Equine Encephalomyelitis in a Gerenuk (Litocranius walleri), Proc. American Association Of Zoo Veterinarians, 1994, p. 324. Swanson WF, Wildt DE, Cambre RC, Citino SB, et al : Reproductive survey of endemic felid species in Latin American zoos: Male reproductive status and implications for conservation, Proc. Amercican Association of Zoo Veterinarians, 1995, pp. 374-380. Klein L, and Citino SB : Comparison of detomidine/carfentanil/ketamine and medetomidine/ketamine anesthesia in Grevy=s zebra, Proc. American Association of Zoo Veterinarians, 1995, pp. 290-295. Schumacher J, Heard DJ, Young, L, and Citino SB : Cardiopulmonary effects of Carfentanil in dama gazelles (Gazella dama), Proc. American Association of Zoo Veterinarians,1995, p. 296. Citino SB : The Use of a Modified, Large Cervid Hydraulic Squeeze Chute for Restraint Of Exotic Ungulates, Proc. American Association of Zoo Veterinarians, 1995, pp. 336-337. Bush M, Munson L, Citino S, Junge R : Anesthesia and preventive health of cheetahs, In: Cheetah Management Manual, IUCN CBSG, Apple Valley, Minnesota, In Press. Bratthauer AD, Fischer DC, Citino SB, Taylor SK, and Montali RJ : Use of 25% EDTA as an improved anticoagulant for some avian species, 15th Annual Proc.