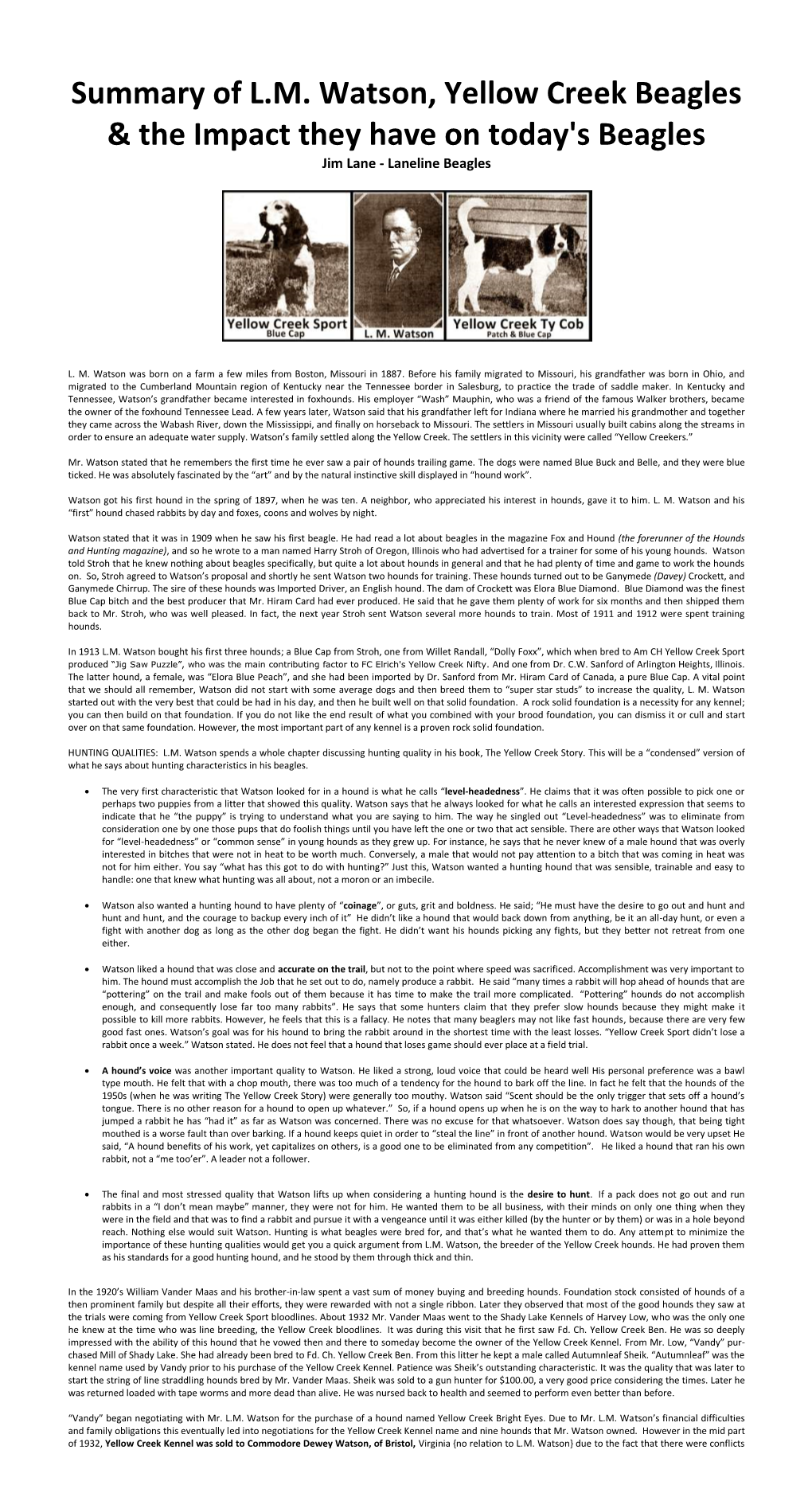

Summary of L.M. Watson, Yellow Creek Beagles & the Impact They

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promote, Preserve, Protect

Annual Hunt Roster Edition Fall 2020 The Magazine of Mounted Foxhunting Promote, Preserve, Protect Helping to Save Foxhunting for Future Generations Starting Point Farm Contents Standing irish Stallions for foxhunting & eventing 3 Letter from the President North America’s largerst breeder of Irish Draughts & Irish Sport Horses 4 MFHA Roster of Foxhound Packs 76 Index of Foxhound Packs by State 77 Membership Application 78 Index of Foxhound Masters 82 Professional Hunt Staff Index 84 Roster of Beagle, Basset and Harrier Packs *Cyan Night RID Dandelion Lord Tim Cover illustration by Tiffany Youngblood, Sweetgum Studio Officers and Directors *Macha Breeze RID OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expires Patrick Anthony Leahy, MFH President Canada • Dr. Charlotte McDonald, MFH .......................................... 2023 6267 E. Thoren Road, Elizabeth, IL 61028 Carolinas • Fred Berry, MFH .....................................................2021 Leslie Rhett Crosby, MFH Central • Arlene Taylor, MFH ....................................................2021 First Vice-President Great Plains • Dr. Luke Matranga, MFH 2022. 2022 Q-Course Sparrow’s Zeus Priscilla Rogers Denegre, MFH Maryland-Delaware • John McFadden, MFH .....................................2023 Second Vice-President Midsouth • Lilla Mason, MFH ...................................................2026 William Haggard, MFH SPF welcomes the foals of 2020! New England • Suzanne Levy, MFH .............................................2024 Secretary-Treasurer New York-New Jersey • David Feureisen, -

Ifaw-Trail-Of-Lies-Full-Report.Pdf

Trail of Lies Report on the role of trail hunting in preventing successful prosecutions against illegal hunters in the UK By Jordi Casamitjana Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................5 2. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................8 2.1. Hunting with dogs.................................................................................................................................8 2.1.1. A typical foxhunting day ............................................................................................................ 11 2.1.2. Cub hunting ............................................................................................................................... 16 2.1.3. Hunting roles ............................................................................................................................. 18 2.2. Drag hunting and bloodhounds hunting ........................................................................................... 22 2.3. The hunting ban ................................................................................................................................. 30 2.4. Enforcement of the hunting ban ....................................................................................................... 36 2.5. The NGOs’ role in the enforcement of the ban ................................................................................ -

Pine Shadows Imprinting

® Today’s Breeder A Nestlé Purina Publication Dedicated to the Needs of Canine Enthusiasts Issue 73 BREEDER PROFILE Pine Shadows Kennel Sunup’s Kennels Warming Up Winter Learning the Ropes Rare Breeds at Purina Farms I especially enjoyed your article Edelweiss-registered dogs have “The Heyday of St. Louis Dog Shows” competed in conformation since the in Issue 72. The Saint Bernard pic- kennel began in 1894. tured winning Best in Show at the Thank you for bringing back mem- 1949 Mississippi Valley Kennel Club ories from our past. Dog Show is CH Gero-Oenz V. Edel - Kathy Knoles weiss, owned and han- Edelweiss Kennels dled by Frank Fleischli, Springfield, IL the second-generation Pro Club members Suzy and Chris owner of Edelweiss Ken - I loved reading about David Holleran feed their Bulldogs, nels. This dog won three Fitzpatrick and the Peke “Malachy” Michelle Gainsley poses her Pekingese, H.T. “Sassy,” above, and “Punkin’,” Bests in Show and the in Issue 72 of Today’s Breeder. I also Purina Pro Plan dog food. feed Purina Pro Plan to my Peke, H.T. Satin Doll, after going Best of Winners at the National Specialty before 2010 Pekingese Club of America National Satin Doll, or “Dolly.” In October, Thank you, Purina, for being blinded in a BB Specialty. “Dolly” also went Best of Opposite Sex. Dolly went Winners Bitch, Best of making Purina Pro Plan gun accident. Winners and Best of Opposite Sex I have been told by other exhibitors dog food. We are Walkin’ I am Frank’s grand- at the Pekingese National in New how wonderful Dolly’s coat is. -

Spring 2017 £3.00 / Volume 9 771476 824001 GUNDOG & ANGLING SPECIAL EDITION Fairs E O M F A

ON SALE TO 12th MAY 2017 Irish COUNTRY SPORTS and COUNTRY LIFE 5.00 € 05 Volume 16 Number 1 Spring 2017 £3.00 / Volume 9 771476 824001 GUNDOG & ANGLING SPECIAL EDITION Fairs e o m f a I r G e l t a greatgamefairs a n e d r G ofireland Irish Game Fair and Fine Food Festival (inc the NI Angling Show) Ireland’s largest Game Fair and international countrysports event featuring action packed family entertainment in three arenas; a Living History Festival including medieval jousting; a Fine Food Festival; a Bygones Area, a huge tented village of trade stands and the top Irish and international countrysports competitions and displays. Shanes Castle, Antrim 24th & 25th June 2017 www.irishgamefair.com Irish Game & Country Fair and Fine Food Festival Main Arena sponsored by the NARGC The ROI’s national Game Fair featuring action packed family entertainment in two arenas; a Living History Village including medieval jousting; a Fine Food Festival; a huge tented village of trade stands and top Irish and International countrysports competitions and displays PLUS all the attractions of the beautiful world famous Birr Castle Demesne. Birr Castle, Co Offaly 26th & 27th August 2017 www.irishgameandcountryfair.com Supported by Irish Countrysports and Country Life magazine (inc The Irish Game Angler) Available as a hard copy glossy quarterly or FREE to READ online at www.countrysportsandcountrylife.com For further details contact: Great Game Fairs of Ireland: Tel: 028 (from ROI 048) 44839167 /44615416 Email: [email protected] Irish COUNTRY SPORTS -

Fox Hunting Algorithm (FHA)

International Conference on Applied Mathematics, Simulation and Modelling (AMSM 2016) A New and Fast Optimization Algorithm: Fox Hunting Algorithm (FHA) Murat Onay Erciyes University, Faculty of Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Turkey Abstract—A new population-based search algorithm called the Optimization algorithms usually have two search Fox Hunting Algorithm (FHA) is presented here. FHA is a mechanisms. The first one is a global search mechanism and general-purpose algorithm that can be applied to solve almost the second one is a local search mechanism. By the experience any optimization problem. The algorithm mimics the fox hunting researchers knows that the local search mechanism must be activity which is formed and improved since 16th century. The modified while searching approaches to the solution. Because algorithm performs some neighborhood searches combined with of that two search mechanisms are not efficient for real world random search. It can be used for both combinatorial problems. So in this optimization algorithm there are three optimization and functional optimization. search mechanisms for searching in a more efficient way. The first one is a global search mechanism; second one is a local Keywords-component; fox hunting algorithm, functional optimization, swarm intelligence search mechanism; third one is the deeper local search mechanism. They are similar to the fox hunting activity. The first search with horses is like global search in the I. INTRODUCTION optimization process; it is fast and searches bigger areas with Classical methods often face great difficulties in solving biggest steps in the whole search mechanism. The second one many complex multi-variable Optimization problems that with trained foxhounds is like local search; it is slower than abound in the real world. -

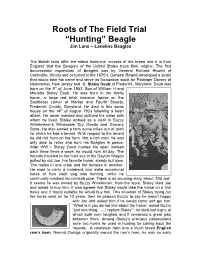

Roots of the Field Trial "Hunting" Beagle

Roots of The Field Trial “Hunting” Beagle Jim Lane – Laneline Beagles The British Isles offer the oldest historical records of the breed and it is from England that the Beagles of the United States trace their origins. The first documented importation of Beagles was by General Richard Rowett of Carlinville, Illinois and occurred in the 1870’s. General Rowett developed a strain that would take his name and serve as foundation stock for Pottinger Dorsey of Newmarket, New Jersey and C. Staley Doub of Frederick, Maryland. Doub was born on the 8th of June 1853, Son of William H and Marietta Staley Doub. He was born in the family home, a large red brick mansion house on the Southeast corner of Market and Fourth Streets, Frederick County, Maryland. He died in this same house on the 14th of August 1933 following a heart attack. He never married and outlived his sister with whom he lived. Staley worked as a clerk in Buzzy Winebrener’s Wholesale Dry Goods and Grocery Store. He also owned a farm some miles out of town for which he had a tenant. With respect to the tenant he did not hunt on the farm. Not a rich man, he was only able to retire and hunt his Beagles in peace. After WW I Staley Doub hunted his open marked pack three times a week, he would hunt all day. The hounds traveled to the hunt site in his Dayton Wagon pulled by old Joe, his favorite horse, steady but slow. The males in one crate and the females in another. -

Hare-Hunting and Harriers : with Notices of Beagles and Basset Hounds

THE -HDrrnNG -uzmss: HHREHDNTIN6 HnDHflECIERS Ha-BRYDE ^-vJ. JOHNA.SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 3 9090 014 537 142 Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University 200 Westboro Road NorthGrafton, MA 01536 T'he Hunting Library EDITED BY F. G. AFLALO, F.R.G.S^ F.Z^. Volume I HARE-HUNTING AND HARRIERS The Hunting Library Edited by F. G. AFLALO, F.R.G.S. Profusely illustrated, stnall dewy ^vo, cloth gilt, -js. dd. net each 7'olume I HARE-HUNTING AND HARRIERS BY H. A. BRYDEN Autlior of " Gun and Camera in Southern Africa," &c. II FOX-HUNTING IN THE SHIRES BY T. F. DALE, M.A. Author of " The History of the Belvoir Hunt," &c. Ill THE MASTER OF HOUNDS C. F. UNDERBILL " Author of " A Century of Fox-Hunting With contributions by Lord Ribblesdale, Lt. -Colonel G. C. Ricardo, Arthur Heinemann, John Scott, &c. London : GRANT RICHARDS 48 Leicester Square, W.C. J'lOiii (in c ngniTini; of the orii;iiiai pnintiui; lunv in tiic .\atn'iuii /oil>,iit (,nlii>y WILLIAM SOMERVILE AUTHOR OK "the CHACK" Platk I HARE-HUNTING AND HARRIERS WITH NOTICES OF BEAGLES AND BASSET HOUNDS BY H. A. BRYDEN AUTHOR OF 'GUN AND CAMERA IN SOUTHERN AFRICA," "NATURE AND SPORT IN SOUTH AFRICA," ETC. ETC. ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY R. B. LODGE AND OTHERS LONDON GRANT RICHARDS 48 LEICESTER SQUARE, W.C. 1903 3 1 '\o3 TO SIR JOHN HEATHCOAT AMORY OF KNIGHTSHAYES COURT, TIVERTON, DEVON BARONET A VETERAN MASTER OF HARRIERS THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR EDITOR'S PREFACE In the following pages a keen all-round sportsman has given what may claim to be in the nature of an exhaustive account, both practical and historic, of hare-hunting. -

Thomas' Hunting Diary, 1905-1906

THOMAS' HUNTING DIARY 1905^1906. !/• fC EDITED BY WALTER M. MAY and ARTHUR W. COATEN. ILLUSTRATED BY MISS DOROTHY HARDY. Price 2/6 Net. PUBLISHED AT "THE COUNTY GENTLEMAN AND LAND AND WATER" OFFICE. 4 AND 5 DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. " i»>iiii i ii;ii . ^ CO Telegraphic Address: " BROWBOUND, LONDON." Telephone: 78+ MAYFAIR. Huntiiig Hats TO H. M THE KING Herbert Johnson, ^^^^>«00ro^^ ^"T"% 38 NEW BOND STREET, LONDON, W. B .ou'^^f^o^^^ H.R.H. The es of Denmark, Leopold of Prussia, H.I.H. The i Frederick H.R H. The lias of Greece. of Clarence and .Avondale, K.G. H.R.H rriiK ie etc., etc. CAMBROyE I7A:CC\RK Htmtiitg and 1{i(Jing Hats. {Yiarhcd success obtained in the fitting of Cadies' Riding I^ats. nylleasuri-s of /lead tal^en by a ne-w method •xhich has proved highly successful in the most difficult eases. ii ( ) ^^ IBv lU'pomtmcnt to ?; ^^ V V "-^f. '!', >o^ '^., iS?' '^O >>"-" ^' HIS MAJESTY THE RING, md H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES. Benson & Hedges,ltd. Importers ofHavana Cigars IN ALL THE LEADING BRANDS. (A LARGE VARIETY SUITABLE FOR HUNTING PURPOSES). Manufacturers &f Importers of Oriental Cigarettes Special Brands: CAIRO EL HOUSSOUN (ClUidcl Trcldc iMark) MAGNOLIA EL KAHLA NEW YORK LONDON MONTREAL 17 West 31ST Street 13 Old Bond Street 183 St. James Street 509 Fifth Avenue W. 74 Broadway 4- THOMAS HUNTING DIARY 1905^1906. EDITED BY WALTER M. MAY and ARTHUR W. COATEN. ILLUSTRATED BY MISS DOROTHY HARDY. PUBLISHED AT "THE COUNTY GENTLEMAN AND LAND AND WATER" OFFICE. -

Report of Committee of Inquiry Into Hunting with Dogs in England &Wales

Report of Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs in England &Wales 9th June 2000 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited On behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office Dd 5067685 6/00 521462 19585 published by The Stationery Office Report of Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs in England &Wales CONTENTS Letter from The Rt. Hon Jack Straw MP ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 1.INTRODUCTION 2.HUNTING 3.HUNTING AND THE RURAL ECONOMY 4.SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ASPECTS 5.POPULATION MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL 6.ANIMAL WELFARE 7.MANAGEMENT AND CONSERVATION OF HABITAT AND OTHER WILDLIFE 8.DRAG AND BLOODHOUND HUNTING 9.PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF HUNTING: THE CONCERNS 10.IMPLEMENTING A BAN APPENDICES 1.Organisations which submitted written evidence, first round 2. Organisations which submitted written evidence, second round 3. Analysis of written evidence submitted by individuals 4.Details of commissioned research 5.Visits undertaken by the Committee 6.Role, rules and recommendations of the Masters' Associations and other organisations 7.A statistical account of hunting in England and Wales 8.Legal provisions relevant to the scope of the Inquiry 9.The international perspective 10.List of abbreviations Report of Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs in England &Wales The Rt. Hon Jack Straw MP Secretary of State for the Home Department 50 Queen Anne's Gate London SW1A 0AA 9 June 2000 You appointed us in December 1999 to carry out an inquiry into hunting with dogs, with the following terms of reference: "To inquire into: the practical aspects of different types of hunting with dogs and its impact on the rural economy, agriculture and pest control, the social and cultural life of the countryside, the management and conservation of wildlife, and animal welfare in particular areas of England and Wales; the consequences for these issues of any ban on hunting with dogs; and how any ban might be implemented. -

A Message from the Chairman of the Trustees

A Message from the Chairman of the Trustees. Redcar Farm Dear All, We wanted you to be aware that an opportunity has arisen to establish kennel huntsman accommodation alongside kennels at Redcar Farm in the valley near Ampleforth. After some initial discussions the Ampleforth Abbey Trustees indicated to us just before Easter that it may be possible for us to take on a lease for Redcar Farm although we should stress there is a long way to go before any final agreement is reached. Such an opportunity to establish a home for the hunt staff and hounds will provide us with a long-term stable arrangement around which we can plan our future and look towards the bicentenary. We will try to keep you informed as and when we can over the next few months. Should any of you have particular expertise/knowledge/ability in respect of the various issues which will arise such as planning or the building work that will be required we hope you will make yourselves known to us as we would be grateful for any assistance over the coming months. We should stress this is only an opportunity at present but, we hope you will agree, it is a very exciting one for the future of the Hunt. Regards, Michael Spencer Toby Pedley parades hounds at Exhibition 2016. L - R Ben Sanders, Henry Kirk, Xavier Wain-Blisset, Toby, Georgina Eglinton, George Crowder Forrard-on into the The Point to Point which Bicentenary! was first started in 1922 was won this year by Edward Plowden (D), in just 21 minutes, equalling the course When Paddy Dunne Cullinan’s mother sent record of James Channer D12 who four couples of beagles over from Ireland to was Captain of Beagling in 2010-11. -

Irish COUNTRY SPORTS and COUNTRY LIFE 5.00 € 02 Volume 15 Number 4 Winter 2016 £3.00 / Volume 9 771476 824001 & IRISH GAME ANGLER MAGAZINE Fairs E O M F A

28th FEBRUARYON SALE 2017TO Irish COUNTRY SPORTS and COUNTRY LIFE 5.00 € 02 Volume 15 Number 4 Winter 2016 £3.00 / Volume 9 771476 824001 & IRISH GAME ANGLER MAGAZINE Fairs e o m f a I r G e l t a greatgamefairs a n e d r G ofireland Irish Game Fair and Fine Food Festival (inc the NI Angling Show) Ireland’s largest Game Fair and international countrysports event featuring action packed family entertainment in three arenas; a Living History Festival including medieval jousting; a Fine Food Festival; a Bygones Area, a huge tented village of trade stands and the top Irish and international countrysports competitions and displays. Shanes Castle, Antrim 24th & 25th June 2017 www.irishgamefair.com Irish Game & Country Fair and Fine Food Festival The ROI’s national Game Fair featuring action packed family entertainment in two arenas; a Living History Village including medieval jousting; a Fine Food Festival; a huge tented village of trade stands and top Irish and International countrysports competitions and displays PLUS all the attractions of the beautiful world famous Birr Castle Demesne. Birr Castle, Co Offaly 26th & 27th August 2017 www.irishgameandcountryfair.com Supported by Irish Countrysports and Country Life magazine (inc The Irish Game Angler) Available as a hard copy glossy quarterly or FREE to READ online at www.countrysportsandcountrylife.com For further details contact: Great Game Fairs of Ireland: Tel: 028 (from ROI 048) 44839167 /44615416 Email: [email protected] Irish COUNTRY SPORTS and COUNTRY LIFE Contents 4 Northern Comment 88 Woodcock Hunting in Ireland Group’s Charity Clay Shoot ROI Comment 5 Success Countryside News 6 90 Winter Wonderland Escape - 36 Lifetime Commitment Awards - By Margaret Annett Top Accolades In Countrysports 92 Pointer & Setter Champion & Conservation Front Cover: An iconic painting of Stake 2016 - by David Hudson ‘The Stag In Moorland’ by John R. -

2559 REC ^ February 1,2007 FEB2 6 REC%

2559 REC ^ February 1,2007 FEB2 6 REC% DogLawAdvisoryBoard: "S%S^%^ Mary Bender, Director Pennsylvania Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement 2301 North Cameron Street Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17110 I am writing on behalf of the Pennsylvania Beagle Gundog Association to comment and provide feedback on the proposed amendments to the Dog Law Regulations Act 225 issued on December 16, 2006. Please see the attached which describes the PBGA. The PBGA is dedicated to support and promote the Beagle for which the breed was originally developed and to support the sport of Beagling which is intended to improve the breed through competition. The following in an excerpt from the American Kennel Club's website providing competition history: Then in 1888, the National Beagle Club was formed and held its first trial. From that time on field trials carrying championship points sprang up rapidly all over the United States, and classes developed for hounds under 13 inches and 13-15 inches. The PBGA would suggest and comment on the proposed law changes which the Bureau of Dog Law Enforcements developing which would impact the members of our association negatively. Please see the below: The PBGA supports the suggestion of removing enforcement from the local district magistrate to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Many of the proposed changes are impractical and burdensome. These changes will not likely improve the conditions in licensed kennels. The proposed regulations will require a substantial increase in manpower with many hours dedicated to filling out bureaucratic reports or recordkeeping. Several areas will be difficult to enforce and the proposed regulations are very general to not include definitions to terms such as: o 20 minute exercise requirements, o Quarantine o A number of standards are poorly worded.