Alice Munro: an Appreciation Michael Boyd Bridgewater State University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exploration of Human Complexities in Alice Munro's Short

The Exploration of Human Complexities in Alice Munro’s Short Stories P. Jayakar Rao M.A, UGC-NET, AP-SET, (Ph.D.) Asst. Professor of English, Govt. Degree & PG College, Siddipet, Telangana India Abstract Alice Munro is a Canadian short story writer and the recipient of many literary honours, including the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature for her work as "master of the contemporary short story", and the 2009 Man Booker International Prize for her lifetime body of work. Munro's work has been described as having reformed the architecture of short stories, especially in its propensity to move forward and backward in time. Her stories explore human complexities in straightforward prose style. Alice Munro, writing about ordinary people in ordinary situations, creates a portrait of life in all of its complexities. In her magnificently textured stories, she explores the distinction of relationships, the profundity of emotions, and the influence that one’s past has on the present. With a few details, she is able to invoke someone’s character or an entire geographical region. Munro is a master at creating a short story that is as fully developed as a novel. Key words: recipient, reformed, propensity, explore, complexities, portrait, profundity, invoke Introduction Canadian writer Alice Munro is considered one of the finest short story writers of the present times. Born in 1931, her highly acclaimed stories chronicle small town life, usually around Ontario, where she grew up, and primarily deal with human relationships, deeper truths and www.ijellh.com 212 ambiguities. In her tales, primarily written from an entirely feminine point of view, the incidents of life get redefined in the inner landscape of intellect and emotion of the narrator / protagonist which in turn are a reflection of the author’s own perceptions. -

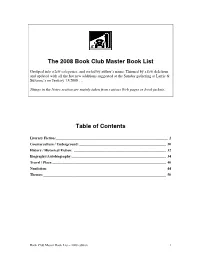

The 2008 Book Club Master Book List Table of Contents

The 2008 Book Club Master Book List Grouped into a few categories, and sorted by author’s name. Thinned by a few deletions and updated with all the hot new additions suggested at the Sunday gathering at Larrie & Suzanne’s on January 13/2008 … Things in the Notes section are mainly taken from various Web pages or book jackets. Table of Contents Literary Fiction:______________________________________________________________ 2 Counterculture / Underground: ________________________________________________ 30 History / Historical Fiction: ___________________________________________________ 32 Biography/Autobiography: ____________________________________________________ 34 Travel / Place:_______________________________________________________________ 40 Nonfiction: _________________________________________________________________ 44 Themes:____________________________________________________________________ 50 Book Club Master Book List – 2008 edition 1 Title / Author Notes Year Literary Fiction: Lucky Jim In Lucky Jim, Amis introduces us to Jim Dixon, a junior lecturer at 2004 (Kingsley Amis) a British college who spends his days fending off the legions of malevolent twits that populate the school. His job is in constant danger, often for good reason. Lucky Jim hits the heights whenever Dixon tries to keep a preposterous situation from spinning out of control, which is every three pages or so. The final example of this--a lecture spewed by a hideously pickled Dixon--is a chapter's worth of comic nirvana. The book is not politically correct (Amis wasn't either), but take it for what it is, and you won't be disappointed. Oryx and Crake Depicts a near-future world that turns from the merely horrible to 2004 (Margaret Atwood) the horrific, from a fool's paradise to a bio-wasteland. Snowman (a man once known as Jimmy) sleeps in a tree and just might be the only human left on our devastated planet. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Identity, Gender, and Belonging In

UNIVERSITY OF DUBLIN, TRINITY COLLEGE Explorations of “an alien past”: Identity, Gender, and Belonging in the Short Fiction of Mavis Gallant, Alice Munro, and Margaret Atwood A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Kate Smyth 2019 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. ______________________________ Kate Smyth i Table of Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: Mavis Gallant Chapter 1: “At Home” and “Abroad”: Exile in Mavis Gallant’s Canadian and Paris Stories ................ 28 Chapter 2: “Subversive Possibilities”: -

Table of Contents

Contents About This Volume, Charles E. May vii Career, Life, and Influence On Alice Munro, Charles E. May 3 Biography of Alice Munro, Charles E. May 19 Critical Contexts Alice Munro: Critical Reception, Robert Thacker 29 Doing Her Duty and Writing Her Life: Alice Munro’s Cultural and Historical Context, Timothy McIntyre 52 Seduction and Subjectivity: Psychoanalysis and the Fiction of Alice Munro, Naomi Morgenstern 68 Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro: Writers, Women, Canadians, Carol L. Beran 87 Critical Readings “My Mother’s Laocoon Inkwell”: Lives of Girls and Women and the Classical Past, Medrie Purdham 109 Who does rose Think She is? Acting and Being in The Beggar Maid: Stories of Flo and Rose, David Peck 128 Alice Munro’s The Progress of Love: Free (and) Radical, Mark Levene 142 Friend of My Youth: Alice Munro and the Power of Narrativity, Philip Coleman 160 in Search of the perfect metaphor: The Language of the Short Story and Alice Munro’s “Meneseteung,” J. R. (Tim) Struthers 175 The complex Tangle of Secrets in Alice munro’s Open Secrets, Michael Toolan 195 The houses That Alice munro Built: The community of The Love of a Good Woman, Jeff Birkenstein 212 honest Tricks: Surrogate Authors in Alice munro’s Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage, David Crouse 228 Narrative, Memory, and Contingency in Alice Munro’s Runaway, Michael Trussler 242 v Alice_Munro.indd 5 9/17/2012 9:01:50 AM “Secretly Devoted to Nature”: Place Sense in Alice Munro’s The View from Castle Rock, Caitlin Charman 259 “Age Could Be Her Ally”: Late Style in Alice Munro’s Too Much Happiness, Ailsa Cox 276 Resources Chronology of Alice Munro’s Life 293 Works by Alice Munro 296 Bibliography 297 About the Editor 301 Contributors 303 vi Critical Insights Alice_Munro.indd 6 9/17/2012 9:01:50 AM. -

"Spelling:" Alice Munro and the Caretaking Daughter

“SPELLING”: ALICE MUNRO AND THE CARETAKING DAUGHTER Debra Nicholson A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2010 Committee: Dr. Bill Albertini, Advisor Dr. Beth Casey, Emeritus © 2010 Debra Nicholson All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Dr. Bill Albertini, Advisor Alice Munro, the renowned Canadian short story writer, has written, over the course of her long career, no fewer than seventeen stories that feature an ill mother as the primary or tangential theme in a daughter’s narrative. While some critics focus on uncovering autobiographical elements of the stories (Munro’s mother endured early-onset Parkinson’s disease), and others vaguely complain that Munro is merely re-writing the same story again and again, no critic has investigated the range and depth of affect produced by maternal illness proffered in her stories, a topic that appears to be a major concern of Munro’s creative life. Not only is it important to analyze the stories of daughters and their ill mothers because of the topic’s importance to Munro, it is essential to illuminate the texts’ contributions to the intersecting discourses of illness, death, and daughters and mothers. This thesis serves to initiate this critical discussion. An analysis of Munro’s story, “Spelling,” provides fruitful material for the discussion of the discourse of caretaking. I track Rose’s caretaking journey by first discussing her entrapment in the gendered norms of caretaking. Then, I argue that Rose capitulates to the discourse of sacrificial caretaking by desiring to care for Flo in a full-time capacity. -

The Love of a Good Woman” Ulrica Skagert University of Kristianstad

Things within Things Possible Readings of Alice Munro’s “The Love of a Good Woman” Ulrica Skagert University of Kristianstad Abstract: Alice Munro’s “The Love of a Good Woman” is perhaps one of the most important stories in her œuvre in terms of how it accentuates the motivation for the Nobel Prize of Literature: “master of the contemporary short story.” The story was first published in The New Yorker in December 1996, and over 70 pages long it pushes every rule of what it means to be categorised as short fiction. Early critic of the genre, Edgar Allan Poe distinguished short fiction as an extremely focused attention to plot, properly defined as that to which “no part can be displaced wit- hout ruin to the whole”. Part of Munro’s art is that of stitching seemingly disparate narrative threads together and still leaving the reader with a sense of complete- ness. The story’s publication in The New Yorker included a subtitle that is not part of its appearing in the two-year-later collection. The subtitle, “a murder, a mystery, a romance,” is interesting in how it is suggestive for possible interpretations and the story’s play with genres. In a discussion of critical readings of Munro’s story, I propose that the story’s resonation of significance lies in its daring composition of narrative threads where depths of meaning keep occurring depending on what aspects one is focusing on for the moment. Further, I suggest that a sense of completion is created in tone and paralleling of imagery. -

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018 www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca # The Boys in the Trees, Mary Swan – 2008 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Mona Awad - 2016 Brother, David Chariandy – 2017 419, Will Ferguson - 2012 Burridge Unbound, Alan Cumyn – 2000 By Gaslight, Steven Price – 2016 A A Beauty, Connie Gault – 2015 C A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews – 2004 Casino and Other Stories, Bonnie Burnard – 1994 A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry – 1995 Cataract City, Craig Davidson – 2013 The Age of Longing, Richard B. Wright – 1995 The Cat’s Table, Michael Ondaatje – 2011 A Good House, Bonnie Burnard – 1999 Caught, Lisa Moore – 2013 A Good Man, Guy Vanderhaeghe – 2011 The Cellist of Sarajevo, Steven Galloway – 2008 Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood – 1996 Cereus Blooms at Night, Shani Mootoo – 1997 Alligator, Lisa Moore – 2005 Childhood, André Alexis – 1998 All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews – 2014 Cities of Refuge, Michael Helm – 2010 All That Matters, Wayson Choy – 2004 Clara Callan, Richard B. Wright – 2001 All True Not a Lie in it, Alix Hawley – 2015 Close to Hugh, Mariana Endicott - 2015 American Innovations, Rivka Galchen – 2014 Cockroach, Rawi Hage – 2008 Am I Disturbing You?, Anne Hébert, translated by The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Wayne Johnston – Sheila Fischman – 1999 1998 Anil’s Ghost, Michael Ondaatje – 2000 The Colour of Lightning, Paulette Jiles – 2009 Annabel, Kathleen Winter – 2010 Conceit, Mary Novik – 2007 An Ocean of Minutes, Thea Lim – 2018 Confidence, Russell Smith – 2015 The Antagonist, Lynn Coady – 2011 Cool Water, Dianne Warren – 2010 The Architects Are Here, Michael Winter – 2007 The Crooked Maid, Dan Vyleta – 2013 A Recipe for Bees, Gail Anderson-Dargatz – 1998 The Cure for Death by Lightning, Gail Arvida, Samuel Archibald, translated by Donald Anderson-Dargatz – 1996 Winkler – 2015 Curiosity, Joan Thomas – 2010 A Secret Between Us, Daniel Poliquin, translated by The Custodian of Paradise, Wayne Johnston – 2006 Donald Winkler – 2007 The Assassin’s Song, M.G. -

Reading Alice Munro, 1973-2013

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2016-02 Reading Alice Munro, 1973-2013 Thacker, Robert University of Calgary Press Thacker, R. "Reading Alice Munro: 1973-2013." University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51092 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca READING ALICE MUNRO, 1973–2013 by Robert Thacker ISBN 978-1-55238-840-2 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Alice Munro, at Home and Abroad: How the Nobel Prize in Literature Affects Book Sales

BNC RESEARCH Alice Munro, At Home And Abroad: How The Nobel Prize In Literature Affects Book Sales + 12.2013 PREPARED BY BOOKNET CANADA STAFF Alice Munro, At Home And Abroad: How The Nobel Prize In Literature Affects Book Sales December 2013 ALICE MUNRO, AT HOME AND ABROAD: HOW THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE AFFECTS BOOK SALES With publications dating back to 1968, Alice Munro has long been a Canadian literary sweetheart. Throughout her career she has been no stranger to literary awards; she’s taken home the Governor General’s Literary Award (1968, 1978, 1986), the Booker (1980), the Man Booker (2009), and the Giller Prize (1998, 2004), among many others. On October 10, 2013, Canadians were elated to hear that Alice Munro had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Since the annual award was founded in 1901, it has been awarded to 110 Nobel Laureates, but Munro is the first Canadian—and the 13th woman—ever to win. In order to help publishers ensure they have enough books to meet demand if one of their titles wins an award, BookNet Canada compiles annual literary award studies examining the sales trends in Canada for shortlisted and winning titles. So as soon as the Munro win was announced, the wheels at BookNet started turning. What happens when a Canadian author receives the Nobel Prize in Literature? How much will the sales of their books increase in Canada? And will their sales also increase internationally? To answer these questions, BookNet Canada has joined forces with Nielsen Book to analyze Canadian and international sales data for Alice Munro’s titles. -

Dynamics of Intimacies in Alice Munro's 'Runaway'

Dynamics of Intimacies in Alice Munro’s ‘Runaway’ A Dissertation Submitted to Department of English For the complete fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts in English Submitted by: Supervised By: Rimsy Ms. Priyanka Sharma Registration No:11605805 Assistant Professor Department of English Lovely Professional University Punjab 2017 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitle ―Dynamics of Intimacies in Alice Munro‘s Runaway‖ is a record of first hand research work done by me during the period of my study in the year 2017 and that this dissertation has not formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associate ship, Fellowship, or other similar title. Place: Jalandhar Signature of the Candidate Date: ii CERTIFICATE I hereby certify that this dissertation entitle ―Dynamics of Intimacies in Alice Munro‘s Runaway‖ by Alice Munro for the award of M.A. degree is a record of research work done by the candidate under my supervision during the period of her subject (2017) and that the dissertation has not formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associate ship, Fellowship, or other similar title and that this dissertation represents independent work on the part of the candidate. Place: Jalandhar Miss Priyanka Sharma Date: Supervisor iii ABSTRACT Alice Munro is regarded as Canadian pure short story writer. Her writing can help enlightening man centric structures which entangle women in traditional gender roles. This dissertation deals with well know work of Alice Munro that is Runaway Stories. This dissertation represents the Dynamics of Intimacies in the relationships in the Runaway Stories. -

Award Winning Novels: Plot Summaries for Books in Bayside's Resource Centre (Courtesy of Chapters Website)

Award Winning Novels: Plot Summaries for Books in Bayside's Resource Centre (Courtesy of Chapters website) Man Booker Award Winners Mantel, Hilary. Bring Up the Bodies. By 1535 Thomas Cromwell, the blacksmith''s son, is far from his humble origins. Chief Minister to Henry VIII, his fortunes have risen with those of Anne Boleyn, Henry''s second wife, for whose sake Henry has broken with Rome and created his own church. But Henry''s actions have forced England into dangerous isolation, and Anne has failed to do what she promised: bear a son to secure the Tudor line. When Henry visits Wolf Hall, Cromwell watches as Henry falls in love with the silent, plain Jane Seymour. The minister sees what is at stake: not just the king''s pleasure, but the safety of the nation. As he eases a way through the sexual politics of the court, and its miasma of gossip, he must negotiate a "truth" that will satisfy Henry and secure his own career. But neither minister nor king will emerge undamaged from the bloody theatre of Anne''s final days. Barnes, Julian. The Sense of An Ending. The story of a man coming to terms with the mutable past, Julian Barnes''s new novel is laced with his trademark precision, dexterity and insight. It is the work of one of the world''s most distinguished writers. Webster and his clique first met Adrian Finn at school. Sex-hungry and book-hungry, they navigated the girl drought of gawky adolescence together, trading in affectations, in-jokes, rumour and wit.