China Vanke (A-1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUNAC CHINA HOLDINGS LIMITED 融創中國控股有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 01918)

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt about any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your licensed securities dealer or registered institution in securities, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional advisers. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Sunac China Holdings Limited, you should at once hand this circular together with the enclosed form of proxy to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s) or to the bank, licensed securities dealer or registered institution in securities or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s). Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. This circular appears for information purposes only and does not constitute an invitation or offer to acquire, purchase or subscribe for any securities. SUNAC CHINA HOLDINGS LIMITED 融創中國控股有限公司 (incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 01918) (1) CONNECTED TRANSACTION — PROPOSED SHARE ISSUANCE UNDER SPECIFIC MANDATE AND (2) APPLICATION FOR WHITEWASH WAIVER Independent Financial Adviser to the Independent Board Committee and the Independent Shareholders Capitalised terms used on this cover shall have the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definition” in this circular, unless the context requires otherwise. -

Three Red Lines” Policy

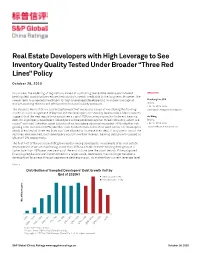

Real Estate Developers with High Leverage to See Inventory Quality Tested Under Broader “Three Red Lines” Policy October 28, 2020 In our view, the widening of regulations aimed at controlling real estate developers’ interest- ANALYSTS bearing debt would further reduce the industry’s overall credit risk in the long term. However, the nearer term may see less headroom for highly leveraged developers to finance in the capital Xiaoliang Liu, CFA market, pushing them to sell off inventory to ease liquidity pressure. Beijing +86-10-6516-6040 The People’s Bank of China said in September that measures aimed at monitoring the funding [email protected] and financial management of key real estate developers will steadily be expanded. Media reports suggest that the new regulations would see a cap of 15% on annual growth of interest-bearing Jin Wang debt for all property developers. Developers will be assessed against three indicators, which are Beijing called “red lines”: whether asset liability ratios (excluding advance) exceeded 70%; whether net +86-10-6516-6034 gearing ratio exceeded 100%; whether cash to short-term debt ratios went below 1.0. Developers [email protected] which breached all three red lines won’t be allowed to increase their debt. If only one or two of the red lines are breached, such developers would have their interest-bearing debt growth capped at 5% and 10% respectively. The first half of the year saw debt grow rapidly among developers. In a sample of 87 real estate developers that we are monitoring, more than 40% saw their interest-bearing debt grow at a faster rate than 15% year over year as of the end of June (see the chart below). -

Evergrande Real Estate Group (Stock Code: 3333.HK)

Evergrande Real Estate Group (Stock code: 3333.HK) 1 Table of Contents • ExecuBve Summary Page 3 • SecBon 1: Fraudulent AccounBng Masks Insolvent Balance Sheet Page 13 • SecBon 2: Bribes, Illegally Procured Land Rights and Severe Idle Land LiabiliBes Page 27 • Secon 3: Crisis Page 39 • SecBon 4: Chairman Hui Page 47 • SecBon 5: Pet Projects Page 52 • Appendix: Recent development Page 57 2 ExecuBve Summary 3 Evergrande Valuaon Evergrande has a market capitalizaon of US$ 8.9bn and trades at 1.6x book value. By market capitalizaon, Evergrande ranks among the top 5 listed Chinese properBes companies. [1] [2] RMB, HKD and USD in billions, except as noted 6/15/2012 in RMB in HKD in USD Share Price 3.80 4.60 0.59 Total Shares Outstanding 14.9 Market Capitalization 56.7 68.7 8.9 + Current Borrowing 10.2 + Non-Current Borrowing 41.5 + Income Tax Liability 11.6 + Cash Advance from Customers 31.6 Subtotal: Debt 95.0 115.0 14.8 - Unrestricted cash (20.1) (24.3) (3.1) Net debt 74.9 90.7 11.7 Enterprise value 131.6 159.4 20.6 Book Value as of 12/31/2011 34.9 Ratio of Equity Market Capitalization to Book Value 1.6x Note: Assuming RMB /USD exchange rate of 6.4 and HKD/ USD exchange rate of 7.75 1] As of June 15, 2012, Evergrande ranked 5th in market capitalizaon behind China Overseas (668 HK), Vanke (000002 SZ), Poly Real Estate (6000048 SH) and China Resources Land (1109 HK) 2] Balance sheet data as of December 31, 2011 4 PercepBon • Evergrande, which primarily operates in 2nd and 3rd Ber ciBes, has grown its assets 23 fold since 2006, becoming the largest condo/ home developer in China. -

Global Offering

(Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: Global Offering Joint Sponsors, Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Leadad ManagersManagers (in alphabetical order) Other Joint Global Coordinator, Joint Bookrunner and Joint Lead Manager Other Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers (in alphabetical order) Project A_PPTUS cover(Eng) Cover size: 210 x 280mm / Open size: 445.3 x 280mm / Spine width: 25.3mm IMPORTANT If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this prospectus, you should obtain independent professional advice. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) GLOBAL OFFERING Number of Offer Shares under : 550,000,000 Shares (subject to the Over- the Global Offering allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Offer Shares : 27,500,000 Shares (subject to reallocation) Number of International Offer Shares : 522,500,000 Shares (including 55,000,000 Reserved Shares under the Preferential Offering) (subject to reallocation and the Over-allotment Option) Maximum Offer Price : HK$22.30 per Share plus brokerage of 1.0%, SFC transaction levy of 0.0027% and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application, subject to refund) Nominal value : US$0.00001 per Share Stock code : 1209 Joint Sponsors, Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers (in alphabetical order) Other Joint Global Coordinator, Joint Bookrunner and Joint Lead Manager Other Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers (in alphabetical order) Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this prospectus. -

The Annual Report on the Most Valuable and Strongest Real Estate Brands June 2020 Contents

Real Estate 25 2020The annual report on the most valuable and strongest real estate brands June 2020 Contents. About Brand Finance 4 Get in Touch 4 Brandirectory.com 6 Brand Finance Group 6 Foreword 8 Executive Summary 10 Brand Finance Real Estate 25 (USD m) 13 Sector Reputation Analysis 14 COVID-19 Global Impact Analysis 16 Definitions 20 Brand Valuation Methodology 22 Market Research Methodology 23 Stakeholder Equity Measures 23 Consulting Services 24 Brand Evaluation Services 25 Communications Services 26 Brand Finance Network 28 © 2020 All rights reserved. Brand Finance Plc, UK. Brand Finance Real Estate 25 June 2020 3 About Brand Finance. Brand Finance is the world's leading independent brand valuation consultancy. Request your own We bridge the gap between marketing and finance Brand Value Report Brand Finance was set up in 1996 with the aim of 'bridging the gap between marketing and finance'. For more than 20 A Brand Value Report provides a years, we have helped companies and organisations of all types to connect their brands to the bottom line. complete breakdown of the assumptions, data sources, and calculations used We quantify the financial value of brands We put 5,000 of the world’s biggest brands to the test to arrive at your brand’s value. every year. Ranking brands across all sectors and countries, we publish nearly 100 reports annually. Each report includes expert recommendations for growing brand We offer a unique combination of expertise Insight Our teams have experience across a wide range of value to drive business performance disciplines from marketing and market research, to and offers a cost-effective way to brand strategy and visual identity, to tax and accounting. -

Sustainable Investment Report Marketing Material Second Quarter 2019 Contents 1 13 Introduction Influence

Sustainable Investment Report Marketing material Second quarter 2019 Contents 1 13 Introduction INfluence Corporate governance: Thinking fast and slow The past, present and future of engaging for better transparency 2 17 INsight Second quarter 2019 "Flygskam": Total company engagement The very real impact of climate change on Swedish airlines Shareholder voting The five practical issues of incorporating Engagement progress ESG into multi-asset portfolios The material consequences of choosing sustainable fashion Trash talk: Why waste might not be wasted What is the Green New Deal and what does it mean for investors? Have we hit a tipping point when it comes to public concern over climate change? Students are striking, extinction rebellions are shutting down our cities, Greta Thunberg is being granted audiences with the most senior politicians and the Greens are making unprecedented inroads at the European Parliament. Jessica Ground Global Head of Stewardship, Schroders We have long viewed public pressure as an However, we are aware that we are asking more of important piece of solving the climate puzzle. our investments than ever before, and run the risk of Our Climate Progress Dashboard tracks the level of overwhelming companies with an endless list of asks. public concern about climate change by using Gallup’s We take stock of the current state of engagement, annual survey on the attitudes of major countries to and set out some important markers for the future. climate change. We assume that if 90% of respondents Meanwhile, in Thinking Fast and Slow on Corporate are concerned about climate change, the rise in global Governance, we attempt to strip governance back to temperatures will be limited to 2°C. -

Company Report: Longfor Properties (00960 HK) Van Liu 刘斐凡 Equity Research Equity 公司报告:龙湖地产 (00960 HK) +86 755 23976672 [email protected]

股 票 研 究 Company Report: Longfor Properties (00960 HK) Van Liu 刘斐凡 Equity Research Equity 公司报告:龙湖地产 (00960 HK) +86 755 23976672 [email protected] 28 March 2017 Benign Prospective Fundamentals with Strong Contracted Sales, Reiterate "Buy" 强劲合约销售下的良好基本面展望,重申“买入” 公 2016 underlying net profit missed our expectation. Top line increased by 司 Rating: Buy 15.6% YoY to RMB54,799 mn. Underlying net profit increased 7.0% YoY to Maintained 报 RMB8,169 mn. 评级: 买入 维持 ( ) 告 The Company is expected to have sustainable revenue growth with Company Report Company stable margins. Contracted sales are likely to experience fast growth despite 目标价 policy tightening. Rental income is expected to grow fast. In addition, a quality 6-18m TP : HK$15.07 Revised from 原目标价: HK$13.22 land bank, appropriate unit land cost (27.6% of ASP in 2016) and low funding costs could result in stable margins. 股价: HK$13.120 Share price The Company is expected to maintain a healthy financial position. We estimate net gearing ratios to gradually decline in 2017-2019 and to maintain Stock performance below 60.0%. 股价表现 We think that Longfor deserves a low NAV discount. We revise up our target price from HK$13.22 to HK$15.07, representing a 24% discount to its 2017E 证 NAV, 7.0x 2017 underlying PER and 1.1x 2017 PBR. Therefore, we reiterate "Buy". Risk: lower-than-expected contracted sales and absent rental income 券 growth. 研 究 2016 年核心净利低于预期。总收入同比增长 15.6%到人民币 54,799 百万元。核心净利同 比上升 7.0%到人民币 8,169 百万元。 报 公司预计获得在稳定利润率下的可持续收入增长。尽管政策收紧但合约销售很有可能快速 告 增长。租金收入将快速增长。另外,有质量的土储,合适的单位土地成本(2016 年销售单 Equity Research Report Research Equity 价的 )以及低的财务成本能导致稳定的利润率。 27.6% 公司能够维持一个健康的财务状况。我们预测净资产负债率在 2017-2019 年逐渐降低并维 Change in Share Price 1 M 3 M 1 Y 股价变动 1 个月 3 个月 1 年 持在 60.0%以下。 Abs. -

Corporate Banking in an Ecosystem World

The power of many: Corporate banking in an ecosystem world August 2019 Authors and acknowledgements Akash Lal Senior Partner Mumbai Daniele Chiarella Senior Partner London Feng Han Partner Shanghai Giulio Romanelli Partner Sydney Markus Röhrig Partner Munich Vincent Zheng Associate Partner Beijing Xing Liu Consultant Beijing The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Roger Rudisuli, Kevin Buehler, Jacob Dahl, Joe Ngai, John Qu, Andras Havas, Istvan Rab, Fumiaki Katsuki, and Shinichiro Oda to this report. The power of many: Corporate banking in an ecosystem world Corporate banking is being transformed by digitization. From core business processes to the way that clients engage and transact, digital has become the sine qua non of almost every action. However, digitization is still in the early stages in corporate banking. As it matures, more fundamental changes will ensue, enabled by the free flow of data between banks, their clients, and third parties. The resulting “ecosystems” will catalyze new operating models and disruption on an unprecedented scale. Already, tech giants such as Alibaba, Tencent, strategies, talent, and IT to do so. They need to and Amazon operate ecosystems with multiple identify potential partners, and determine which businesses. Some already offer financial services, business models work best for them. The task is from trade finance, to payments and marketplace nuanced and complex, but in a world of increasing lending. The implication of these changes is that the competition, it represents an opportunity that traditional boundaries between corporate banks cannot be ignored. and the industries they serve can no longer be taken for granted. In an ecosystem context, information, Corporate banking’s performance resources, and expertise have coalesced; everything challenge is up for grabs. -

Bay to Bay: China's Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US And

June 2021 Bay to Bay China’s Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US and San Francisco Bay Area Business Acknowledgments Contents This report was prepared by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute for the Hong Kong Trade Executive Summary ...................................................1 Development Council (HKTDC). Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Institute, led the analysis with support from Overview ...................................................................5 Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute who co-authored Historic Significance ................................................... 6 the paper. The Economic Institute is grateful for the valuable information and insights provided by a number Cooperative Goals ..................................................... 7 of subject matter experts who shared their views: Louis CHAPTER 1 Chan (Assistant Principal Economist, Global Research, China’s Trade Portal and Laboratory for Innovation ...9 Hong Kong Trade Development Council); Gary Reischel GBA Core Cities ....................................................... 10 (Founding Managing Partner, Qiming Venture Partners); Peter Fuhrman (CEO, China First Capital); Robbie Tian GBA Key Node Cities............................................... 12 (Director, International Cooperation Group, Shanghai Regional Development Strategy .............................. 13 Institute of Science and Technology Policy); Peijun Duan (Visiting Scholar, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Connecting the Dots .............................................. -

STOXX Hong Kong All Shares 50 Last Updated: 01.12.2016

STOXX Hong Kong All Shares 50 Last Updated: 01.12.2016 Rank Rank (PREVIOUS ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) ) KYG875721634 BMMV2K8 0700.HK B01CT3 Tencent Holdings Ltd. CN HKD Y 128.4 1 1 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 69.3 2 2 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 60.3 3 4 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 57.5 4 3 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 37.7 5 5 CNE1000001Z5 B154564 3988.HK CN0032 BANK OF CHINA 'H' CN HKD Y 32.6 6 7 KYG217651051 BW9P816 0001.HK 619027 CK HUTCHISON HOLDINGS HK HKD Y 32.0 7 6 HK0388045442 6267359 0388.HK 626735 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing HK HKD Y 28.5 8 8 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 26.5 9 9 CNE1000002L3 6718976 2628.HK CN0043 China Life Insurance Co 'H' CN HKD Y 20.4 10 15 HK0016000132 6859927 0016.HK 685992 Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. HK HKD Y 19.4 11 10 HK0883013259 B00G0S5 0883.HK 617994 CNOOC Ltd. CN HKD Y 18.9 12 12 HK0002007356 6097017 0002.HK 619091 CLP Holdings Ltd. HK HKD Y 18.3 13 13 KYG2103F1019 BWX52N2 1113.HK HK50CI CK Property Holdings HK HKD Y 17.9 14 11 CNE1000002Q2 6291819 0386.HK CN0098 China Petroleum & Chemical 'H' CN HKD Y 16.8 15 14 HK0688002218 6192150 0688.HK 619215 China Overseas Land & Investme CN HKD Y 14.8 16 16 HK0823032773 B0PB4M7 0823.HK B0PB4M Link Real Estate Investment Tr HK HKD Y 14.6 17 17 CNE1000003W8 6226576 0857.HK CN0065 PetroChina Co Ltd 'H' CN HKD Y 13.5 18 19 HK0003000038 6436557 0003.HK 643655 Hong Kong & China Gas Co. -

China Reits Property Landlords to Shine 19

SECTOR BRIEFING number DBS Asian Insights DBS Group59 Research • May 2018 China REITs Property Landlords to Shine 19 DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 59 02 China REITs Property Landlords to Shine Ken HE Equity Analyst DBS (Hong Kong) [email protected] Carol WU Head of Greater China Research DBS (Hong Kong) [email protected] Danielle WANG CFA Equity Analyst DBS (Hong Kong) [email protected] Derek TAN Equity Analyst DBS Group Research [email protected] Jason LAM Equity Analyst DBS (Hong Kong) [email protected] Produced by: Asian Insights Office • DBS Group Research go.dbs.com/research @dbsinsights [email protected] Goh Chien Yen Editor-in-Chief Jean Chua Managing Editor Martin Tacchi Art Director 19 DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 59 03 04 Executive Summary 08 China REITs Are Lagging Edging Towards Onshore REITs Major Obstacles in Fostering 18 an Onshore REIT Regime CMBS/CMBNs Are Growing Faster C-REITs Are Imminent Which Asset Type Will Benefit 28 More? Modern Logistics Properties The Rise of Active Property Asset Management Which Developer Will Benefit From the Establishment of C-REITs? 49 Appendix DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 59 04 Executive Summary No REIT regime yet he real estate investment trust (REIT) has become an important investment vehicle as evidenced by its separation from the financial sector in the Global Industry Classification Standard as a sector on its own. Major Asian countries/regions have joined western countries to kickstart local versions of REITs, leaving China the last Tbig economy that has yet to have such an investment vehicle. Two major technical In our view, removing legislative obstacles (publicly traded funds are not allowed to obstacles hold commercial properties) is the first step that the government needs to take towards establishing a modern REIT regime. -

Vanke - a (000002 CH) BUY (Initiation) Steady Sales Growth Target Price RMB31.68 Up/Downside +16.8% Current Price RMB27.12 SUMMARY

10 Jun 2019 CMB International Securities | Equity Research | Company Update Vanke - A (000002 CH) BUY (Initiation) Steady sales growth Target Price RMB31.68 Up/downside +16.8% Current Price RMB27.12 SUMMARY. We initiate coverage with a BUY recommendation on Vanke – A share. Vanke is a pioneer in China property market, in terms of leasing apartment, prefabricated construction and etc. We set TP as RMB31.68, which is equivalent to China Property Sector past five years average forward P/E of 9.0x. Upside potential is 16.8%. Share placement strengthened balance sheet. Vanke underwent shares Samson Man, CFA placement and completed in Apr 2019. The Company issued and sold 263mn (852) 3900 0853 [email protected] new H shares at price of HK$29.68 per share. The newly issued H shares represented 16.67% and 2.33% of the enlarged total issued H shares and total Chengyu Huang issued share capital, respectively. Net proceeds of this H shares placement was (852) 3761 8773 HK$7.78bn and used for debt repayment. New capital can flourish the balance [email protected] sheet although net gearing of Vanke was low at 30.9% as at Dec 2018. Stock Data Bottom line surged 25% in 1Q19. In 1Q19, revenue and net profit surged by Mkt Cap (RMB mn) 302,695 59.4% to RMB48.4bn and 25.2% to RMB1.12bn, respectively. The slower growth Avg 3 mths t/o (RMB mn) 1,584 in bottom line was due to the scale effect. Delivered GFA climbed 88.2% to 52w High/Low (RMB) 33.60/20.40 3.11mn sq m in 1Q19 but only represented 10.5% of our forecast full year Total Issued Shares (mn) 9.742(A) 1,578(H) delivered GFA.