Scene on Radio Little War on the Prairie (Seeing White, Part 5): Transcript Part-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Episode 2: the Breakup

Episode 2: The Breakup Detective Why don’t you go ahead and tell us what you know about the death of Hae Lee. Jay Ok. Ira Glass Previously, on Serial. Detective So he wanted an alibi. Jay Yes. Adnan The only thing I can say is, man, it was just a normal day to me. There was absolutely nothing abnormal about that day to me. Detective She was concerned because she was being asked questions about an affidavit she had written. Asia McClain Even now, it would be nice if there was some technicality that then would prove his innocence. Great. Sarah Koenig But I think, I think, Asia, like, you might be that technicality. Automated voice This is a Global-Tel link prepaid call from Adnan Syed an inmate at a Maryland Correctional facility… Sarah Koenig From This American Life and WBEZ in Chicago, it’s Serial. One story week by week. I’m Sarah Koenig. We’re at episode two. You probably heard episode one on This American Life, or through our website, SerialPodcast.org, but if you haven’t, stop. Go back to the beginning. We’re telling this story in order, the story of Hae Min Lee, an 18-year-old girl, who was killed in Baltimore in 1999, and the story of Adnan Syed, her ex-boyfriend who was convicted of the crime. So to pick up where we left off, last episode, you heard how the prosecution told the story of this murder at Adnan’s trial. And the motive the State supplied, the basis for the whole thing, was that after Hae broke up with Adnan, he couldn’t accept it. -

Tossups by Alice Gh;,\

Tossups by Alice Gh;,\. ... 1. Founded in 1970 with a staff of 35, it now employs more than 700 people and has a weekly audience of over 23 million. The self-described "media industry leader in sound gathering," its ·mission statement declares that its goal is to "work in partnership with member stations to create a more informed public." Though it was created by an act of Congress, it is not a government agency; neither is it a radio station, nor does it own any radio stations. FTP, name this provider of news and entertainment, among whose most well-known products are the programs Morning Edition and All Things Considered. Answer: National £ublic Radio . 2. He's been a nanny, an insurance officer and a telemarketer, and was a member of the British Parachute Regiment, earning medals for service in Northern Ireland and Argentina. One of his most recent projects is finding a new lead singer for the rock band INXS, while his less successful ventures include Combat Missions, The Casino, and The Restaurant. One of his best-known shows spawned a Finnish version called Diili, and shooting began recently on a spinoff starring America's favorite convict. FTP, name this godfather of reality television, the creator of The Apprentice and Survivor. Answer: Mark Burnett 3. A girl named Fern proved helpful in the second one, while Sanjay fulfilled the same role during the seventh. Cars made of paper, plastic pineapples, and plaster elephants have been key items, and participants have been compelled to eat chicken feet, a sheep's head, a kilo of caviar, and four pounds of Argentinian barbecue, although not all in the same season. -

Family Violence Frontmatter 2/24/04 9:13 AM Page 1

Family Violence Frontmatter 2/24/04 9:13 AM Page 1 Family Violence Family Violence Frontmatter 2/24/04 9:13 AM Page 2 Other Books in the Current Controversies Series: The Abortion Controversy Marriage and Divorce Alcoholism Medical Ethics Assisted Suicide Mental Health Capital Punishment Minorities Censorship Nationalism and Ethnic Computers and Society Conflict Conserving the Environment Native American Rights Crime Police Brutality The Disabled Politicians and Ethics Drug Legalization Pollution Drug Trafficking Prisons Ethics Racism Europe Reproductive Technologies Free Speech The Rights of Animals Gambling Sexual Harassment Garbage and Waste Smoking Gay Rights Suicide Guns and Violence Teen Addiction Hate Crimes Teen Pregnancy and Parenting Hunger Urban Terrorism Illegal Drugs Violence Against Women Illegal Immigration Violence in the Media The Information Highway Women in the Military Interventionism Youth Violence Iraq Family Violence Frontmatter 2/24/04 9:13 AM Page 3 Family Violence J.D. Lloyd, Book Editor David Bender, Publisher Bruno Leone,Executive Editor Bonnie Szumski, Editorial Director Stuart Miller, Managing Editor CURRENT CONTROVERSIES Family Violence Frontmatter 2/24/04 9:13 AM Page 4 No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical, or otherwise, including, but not limited to, photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, with- out prior written permission from the publisher. Cover photo: © Tony Stone Images/Claudia Kunin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Family violence / J.D. Lloyd, book editor. p. cm. — (Current controversies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7377-0451-9 (pbk) — ISBN 0-7377-0452-7 (lib) 1. -

Radio-Aig for PDF CS6.Indd 1 7/23/12 1:00 PM

radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 1 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 2 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 3 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 4 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 5 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 6 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 7 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 8 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 9 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 10 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 11 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 12 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 13 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 14 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 15 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 16 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 17 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 18 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 19 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 20 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 21 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 22 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 23 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 24 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 25 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 26 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 27 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 28 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 29 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 30 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 31 7/23/12 1:00 PM radio-aIG for PDF CS6.indd 32 7/23/12 1:00 PM STAFF In April 1999 (when this comic was written) This American Life was produced by Ira Glass, Julie Snyder, Alix Spiegel and Nancy Updike, with help from Todd Bachmann, Jorge Just and Sylvia Lemus. -

Disserta__O___Diogo Tognolo R

PARA ALÉM DE UMA DÚVIDA RAZOÁVEL: Serial e a busca da verdade Diogo Tognolo Rocha UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação Social Diogo Tognolo Rocha PARA ALÉM DE UMA DÚVIDA RAZOÁVEL: Serial e a busca da verdade Belo Horizonte 2018 Diogo Tognolo Rocha PARA ALÉM DE UMA DÚVIDA RAZOÁVEL: Serial e a busca da verdade Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação Social da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Comunicação Social. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Bruno Souza Leal Coorientadora: Profª. Drª. Sônia Caldas Pessoa Linha de pesquisa: Textualidades Midiáticas Belo Horizonte 2018 301.16 Rocha, Diogo Tognolo R672p Para além de uma dúvida razoável [manuscrito] : serial e 2018 a busca da verdade / Diogo Tognolo Rocha. - 2018. 147 f. Orientador: Bruno Souza Leal. Coorientador: Sônia Caldas Pessoa. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.Comunicação – Teses. 2. Podcasters - Teses 3.Jornalismo - Teses I. Leal, Bruno Souza. II. Pessoa, Sônia Caldas. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV. Título. AGRADECIMENTOS O percurso da pós-graduação é muitas vezes solitário e desafiador. Poder contar com amigos e colegas ao longo desse caminho fez com que a experiência fosse muito mais prazerosa. A todos que ajudaram com contribuições, seja na pesquisa, seja na amizade, meu muito obrigado. Ao Bruno e a Sônia, que fizeram desses dois anos momentos de aprendizado e afeto. Obrigado pela paciência, pelos ensinamentos e pelo carinho com que sempre trataram meu trabalho e minha formação como pesquisador. -

Spare Times for Oct. 30-Nov. 5

http://nyti.ms/1kf8BNw ARTS Spare Times for Oct. 30-Nov. 5 By JOSHUA BARONE OCT. 29, 2015 Around Town Information on events for possible inclusion in Spare Times should be sent to [email protected] by Friday at 5 p.m. for publication that week. Longer versions of Around Town and For Children listings are in a searchable guide at nytimes.com/events. Museums and Sites American Museum of Natural History: ‘Countdown to Zero’(continuing) Smallpox is the only human disease to have been eradicated, but what about Guinea worm, polio, malaria and others? This exhibition, presented in collaboration with the Carter Center, examines international efforts to control and wipe out infection. Daily from 10 a.m. to 5:45 p.m., Central Park West and 79th Street, 212-769-5200, amnh.org. Brooklyn Historical Society: ‘Brooklyn Americans: Hockey’s Forgotten Promise’(through March 27) The New York Islanders may be new to Brooklyn, but the borough isn’t new to hockey. This exhibition tells the story of its first National Hockey League team, the Brooklyn Americans. The team wore red, white and blue jerseys and represented Kings County at the height of World War II and in the early days of the N.H.L. Still, as the exhibition shows, the team was unsuccessful and ultimately financially doomed. 128 Pierrepont Street, near Clinton Street, Brooklyn Heights, 718- 222-4111, brooklynhistory.org. ‘Global Citizen: The Architecture of Moshe Safdie’(through Jan. 10) This touring exhibition, a retrospective of Mr. Safdie’s career of more than 50 years, makes its way to New York with new material based on the architect’s recent work related to dense urbanism in Asia. -

Chris Brookes

Praise for Reality Radio: Telling True Stories in Sound “Somehow in this manic digital age, Reality Radio—a mere book! —is more relevant than ever. Form and function manifest, here is the story of contemporary documentary audio, thoughtfully composed and offered straight from its most respected producers. Reality Radio is required reading for anyone at the beginning of her audio career. Or in the middle. Or finishing up. And for all invested listeners. This is radio canon.” —Julie Shapiro, executive producer, Radiotopia from prx “The essays in this book were written by people thinking with their ears.” —rick Moody, author and audio maker “[Biewen] offers a lively history of creative documentary radio in his introduction to [twenty-five] passionate, instructive, and unex- pectedly moving essays by innovative audio journalists and artists who use sound to tell true stories artfully. Invaluable and many- faceted coverage of a thriving, populist, and mind- expanding art form.” —Booklist “What is striking about this collection is how clearly the reader can ‘hear’ the diverse voices and stories, despite the print medium. A wonderful and accessible read. Highly recommended.” —Choice “An incredibly important contribution to the field of public media, one that will invite introspection, spark creativity, and hopefully teach people that the first step in learning is listening.” —Public Radio Makers Quest 2.0 “The producers who wrote these essays prove that there’s nothing more moving than real, truthful radio. I read a lot of the book in bed and soon heard the voices whispering in my ear: ‘Get up. Go record something. Now.’ You will feel the same.” — NeeNah elliS, independent radio producer and author of If I Live to Be 100: Lessons from the Centenarians “In [these] highly autobiographical essays . -

POL3235W: Democracy & Citizenship

DRAFT SYLLABUS—EDITS MAY BE MADE BEFORE THE BEGINNING OF CLASS Instructor: Christopher Stone SSB 737 [email protected] Office Hours: Mon. 4:15-5:15, and by appointment POL3235W: Democracy & Citizenship Key Dates Paper 1 Draft 1: June 28 Paper 2 Draft 1: July 12 Final Drafts Paper 1 & 2: August 2 Final Presentation: August 2 Course Description Democracy seems to be an intuitively simple concept to many Americans. Americans know what democracy, and the corresponding values of freedom and equality mean because they live under a democratic system of government that guarantees liberty and justice for all, and equality regardless of race, color, national origin, religion, or sex. Likewise, Americans know that being a citizen means we have certain rights. (and duties?) When we delve a little deeper into what these concepts mean, however, we discover that this apparent certainty papers over a host of disagreements, divisions, and uncertainties. These complexities have bubbled up to the surface today, as they have historically, through a number of contemporary concerns espoused by the Occupy Movement, the Tea Party Movement, Black Lives Matter, anti-establishment politics, etc. This class helps students to engage in the contemporary problems of democracy by grounding the conversation in the historical debates of democratic theory. Rather than suggesting any simple answers, our class will instead pose questions with which we, together, must wrestle. What is the democracy? How should we understand basic concepts of democracy like freedom, equality, and solidarity? How should we respond when these concepts come into conflict? Is capitalism inherently in conflict with democracy? Working through these questions, we will tack back and forth between theoretical debates and contemporary and historical political problems, gaining a more nuanced understanding of the political stakes behind these questions, as well as a more critical perspective from which to understand the political challenges of this moment in history. -

New York University Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute Syllabus JOUR

New York University Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute Syllabus JOUR-UA-202 SPECIALIZED REPORTING: PODCASTING Summer 2021 Professor: Todd Whitney Mondays & Thursdays 9a-12p EST 20 Cooper Square, Room TBD/Zoom To contact professor: [email protected] Office hours: TBD Course Description Podcasting has become one of the premiere mediums for creative storytelling and journalism. In this summer course, students will learn to craft compelling stories solely in sound. By the end of the summer session, they will complete professional-quality pieces to add to their portfolios. Students will engage podcasting as an art unto itself while developing storytelling skills useful in any medium. They'll learn essential skills like field recording, editing tape with software, and sound design. They'll also develop the research and interview techniques necessary to craft compelling audio narratives. Importantly, students will develop their own creative voices and abilities to explain the world through sound. Learning Objectives Demonstrate the ability to exercise journalism’s core ethical values as well as: ❑ Learn the elements of audio reportage ❑ Produce thoughtful and engaging audio stories ❑ Demonstrate critical thinking, independence, and creativity appropriate for producing media in a democratic society ❑ Interview subjects, conduct research, and evaluate information ❑ Work ethically in pursuit of truths, accuracy, fairness, and diverse perspectives ❑ Use technological tools and apply quantitative concepts as appropriate Course Structure A typical class will be structured as such: 1. Discuss the previous class’ assignment 2. Case studies, discussion, lecture, listening, exercise 3. Workshopping Readings Outside of class there will be additional readings, fieldworks, and story production. There’s a good amount of homework but by the end of the semester your focus will be on your projects. -

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

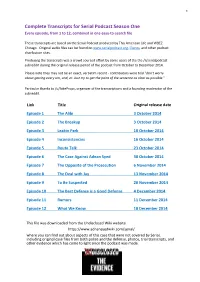

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

Serial Episode 12: “What We Know”

Serial Episode 12: “What we Know” Ira Glass: Previously, on Serial… Jay: He left his cell phone in the car with me, told me he’d call me. Detective Ritz: And now at this point, do you know why he’s leaving the car with you? Jay: Yes. Detective Ritz: And why is that? Jay: Because he said he’s going to kill Hae. Adnan Syed: I definitely understand that someone could look at this and say, “oh, you know he must be lying, it’s so coincidental.” Nisha: He told me to speak with Jay and I was like “ok,” because Jay wanted to say hi, so I said hi to Jay and that’s all I can really recall. Sarah Koenig: The uselessness of what we’re trying to do by recreating something that doesn’t fit, it’s like trying to plot the coordinates of someone’s dream or something. Adnan Syed: You know, perhaps I’ll never be able to explain it and it is what it is, if someone believes me or not, I have no control over it. Automated voice: This is a Global-Tel link prepaid call from Adnan Syed an inmate at a Maryland Correctional facility. This call will be recorded and monitored. If you wish to... Sarah Koenig: From This American Life and WBEZ Chicago it’s Serial. One story told week by week. And this, Episode Twelve is the final week, final episode of Season One of this podcast. It’s been a year since I first contacted Adnan and I’m still talking to him regularly. -

2013 Contest Categories

2013 Contest Categories The Education Writers Association National Awards in Education Reporting honor exceptional work covering stories that add to the understanding of education from early childhood through college and beyond. Entries will be judged on criteria that include the quality of writing, clarity, insight, innovative presentation, deadline pressures, and explanation of issues. Please note that the categories have changed and that applicants should review them all before entering their submissions. For example, we have added a category designated exclusively for data reporting. * In calculating the staff size, please consider all the FTE employees in the newsroom who contribute to a finished product. In addition to reporters, the calculation should include, among others, all editors, designers, online producers and multimedia content producers, such as photographers, data analysts and videographers. I. GENERAL NEWS OUTLETS, SMALL NEWSROOM Print or online journalism publications with 25 or fewer FTE newsroom staffers. Written sources of education news, such as dailies and news blogs, are eligible. A. Single-Topic News or Feature: First Prize: “Promise to Renew” by Sara Neufeld of The Hechinger Report and NJ Spotlight • http://bit.ly/1ho6VKM • http://bit.ly/1jqNkxt • http://bit.ly/1aPC59H “Beautifully written package of the stories about the challenges of teaching students with special needs. Sara Neufeld takes readers into the schools and classrooms, where they can get a taste of both the struggles and challenges of the children and the difficulties and stresses faced by the teachers and why there is a high turnover rate among them. She balances the experiences at one school with what is going on in the broader environment of special education.” “A superlative series that lays out the challenge of education reform in one of the most grueling settings.