Three Angry Men: an Augmented-Reality Experiment in Point-Of-View Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop Miege SUMMER READING LIST

Bishop Miege SUMMER READING LIST All students are required to read the selections AdditionAl optionAl reAding suggestions listed for their grades and levels of English. Testing over summer reading will take place the first week To encourage reading throughout the summer, the Bishop Miege English Department has put together a list of titles that students should have read before they go to college. of school. Students will not be responsible for Novels that will be required reading throughtout the students’ four years at Miege are taking notes along with their reading. However, indicated by an asterisk (*). The list is intended not only to prepare students for college highlighting and annotating in your own book but also to encourage a lifelong reading habit. We hope you make the rest of the list a goal is highly encouraged. for your own completion. Happy reading! Junior level AP students must write a paper based on their reading within the first quarter To Kill a Mockingbird, *Othello, William *The Scarlet Letter, of school. It is helpful to take chapter notes Harper Lee Shakespeare Nathaniel Hawthorne Of Mice and Men, The Old Man and the Sea, The Piano Lesson, marking specific quotes and literary devices to John Steinbeck Ernest Hemingway August Wilson be used in their paper. A notebook of summaries Lord of the Flies, Brave New World, The Joy Luck Club, Amy Tan might help note specific passages without having William Golding Aldous Huxley *The Glass Menagerie, *Night, Elie Weisel *Siddhartha, Tennessee Williams to review the entire text. *The Catcher in the Rye, Hermann Hesse Miracle Worker, J.D. -

Table of Contents

GEVA THEATRE CENTER PRODUCTION HISTORY TH 2012-2013 SEASON – 40 ANNIVERSARY SEASON Mainstage: You Can't Take it With You (Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman) Freud's Last Session (Mark St. Germain) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Next to Normal (Music by Tom Kitt, Book/Lyrics by Brian Yorkey) The Book Club Play (Karen Zacarias) The Whipping Man (Matthew Lopez) A Midsummer Night's Dream (William Shakespeare) Nextstage: 44 Plays For 44 Presidents (The Neofuturists) Sister’s Christmas Catechism (Entertainment Events) The Agony And The Ecstasy Of Steve Jobs (Mike Daisey) No Child (Nilaja Sun) BOB (Peter Sinn Nachtrieb, an Aurora Theatre Production) Venus in Fur (David Ives, a Southern Repertory Theatre Production) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2011-2012 SEASON Mainstage: On Golden Pond (Ernest Thompson) Dracula (Steven Dietz; Adapted from the novel by Bram Stoker) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Perfect Wedding (Robin Hawdon) A Raisin in the Sun (Lorraine Hansberry) Superior Donuts (Tracy Letts) Company (Book by George Furth, Music, & Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim) Nextstage: Late Night Catechism (Entertainment Events) I Got Sick Then I Got Better (Written and performed by Jenny Allen) Angels in America, Part One: Millennium Approaches (Tony Kushner, Method Machine, Producer) Voices of the Spirits in my Soul (Written and performed by Nora Cole) Two Jews Walk into a War… (Seth Rozin) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2010-2011 SEASON Mainstage: Amadeus (Peter Schaffer) Carry it On (Phillip Himberg & M. -

Twelve Angry Men: a Twenty-First Century Reflection of Race, Art, and Incarceration

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2021 Twelve Angry Men: A Twenty-First Century Reflection of Race, Art, and Incarceration Mackenzie A. Gross Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Africana Studies Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Legal Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Social Justice Commons Recommended Citation Gross, Mackenzie A., "Twelve Angry Men: A Twenty-First Century Reflection of Race, Art, and Incarceration" (2021). Honors Theses. 557. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/557 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i ii Twelve Angry Men: A Twenty-First Century Reflection of Race, Art, and Incarceration By Mackenzie A. Gross A Proposal Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in Department/Program 10/20/20 Approved By: Advisor signature: John Hunter Co-advisor or 2nd Reader: Carl Milofsky Co-advisor or 3rd Reader: Bryan Vandevender Department Chairperson: John Hunter Honors Council Representative: Ken Eisenstein iii Acknowledgments This paper is dedicated to Joel Carl, Tito McGill, Derrick Stevens, Rich Woodward, Tony Gomez and Rob Beckelback for opening my eyes to the work I want to dedicate my life to. I would not be here without you. Knowing you is a gift. Thank you to President John Bravman for being so present for your students. -

ELA English IIIC Unit 2 Teacher Resources.Pdf

Twelve Angry Men by REGINALD ROSE The following play was written for television. It begins with a list of characters, but on television you would not have the benefit of that list (although, of course, you would be able to tell something about each character from his appearance on the screen). Imagine, then, on the screen of your mind the scene described at the start: a courtroom, with the area, or box, in the foreground for the twelve members of the jury. The kinds of men they are will become clear as the play unfolds. One suggestion, though: pay particular attention to juror NO. 8: And it might be helpful to fix your mind the equation: 7+3=10. For jurors 7, 3, and 10 also play extremely important parts. CHARACTERS FOREMAN: A small, petty man who is impressed with the authority he has and handles himself quite formally. Not overly bright, but dogged. JUROR NO. 2: A meek, hesitant man who finds it difficult to maintain any opinions of his own. Easily swayed and usually adopts the opinion of the last person to whom he has spoken. JUROR NO. 3: A very strong, very forceful, extremely opinionated man within whom can be detected a streak of sadism. He is a humorless man who is intolerant of opinions other than his own and accustomed to forcing his wishes and views upon others. JUROR NO. 4: Seems to be a man of wealth and position. He is a practiced speaker who presents himself well at all times. He seems to feel a little bit above the rest of the jurors. -

Angels in America

Angels in America Part One Millennium Approaches Part Two Perestroika Belvoir presents Angels in America A Gay Fantasia on National Themes Part One Millennium Approaches Part Two Perestroika By TONY KUSHNER Director EAMON FLACK This production of Angels in America opened at Belvoir St Theatre on Saturday 1 June 2013. It transferred to Theatre Royal, Sydney, on Thursday 18 July 2013. Set Designer With MICHAEL HANKIN The Angel / Emily Costume Designer PAULA ARUNDELL MEL PAGE Louis Ironson Lighting Designer MITCHELL BUTEL NIKLAS PAJANTI Roy M. Cohn Associate Lighting Designer MARCUS GRAHAM ROSS GRAHAM Harper Amaty Pitt Composer AMBER McMAHON ALAN JOHN Prior Walter Sound Designer LUKE MULLINS STEVE FRANCIS Rabbi Isidor Chemelwitz / Hannah Assistant Director Porter Pitt / Ethel Rosenberg / Aleksii SHELLY LAUMAN ROBYN NEVIN Fight Director Belize / Mr Lies SCOTT WITT DEOBIA OPAREI American Dialect Coach Joseph Porter Pitt PAIGE WALKER-CARLTON ASHLEY ZUKERMAN Stage Manager All other characters are played by MEL DYER the company. Assistant Stage Manager ROXZAN BOWES Angels in America is presented by arrangement with Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd, on behalf of Josef Weinberger Ltd of London. Angels in America was commissioned by and received its premiere at the Eureka Theatre, San Francisco, in May 1991. Also produced by Centre Theatre Group/ Mark Taper Forum of Los Angeles (Gordon Davidson, Artistic Director/Producer). Produced in New York at the Walter Kerr Theatre by Jujamcyn Theatres, Mark Taper Forum with Margo Lion, Susan Quint Gallin, Jon B. Platt, The Baruch-Frankel-Viertel Group and Frederick Zollo in association with Herb Alpert. PRODUCTION THANKS José Machado, Jonathon Street and Positive Life NSW; Tia Jordan; Aku Kadogo; The National Association of People with HIV Australia. -

Nashville for Over 20 Years

Pictured from left to right: Matthew Harrison Jarrod Grubb Renee Chevalier Rita Mitchell Laura Folk Mary Carlson Vice President Vice President Vice President Senior Vice President Senior Vice President Vice President Relationship Relationship Relationship Private Client Services Medical Private Relationship Manager Manager Manager Banking Manager POWERING YOUR today a d tomorrow Personal Advantage Banking from First Tennessee. The most exclusive way we power the dreams of those with exclusive financial needs. After all, you’ve been vigilant in acquiring a certain level of wealth, and we’re just as vigilant in finding sophisticated ways to help you achieve an even stronger financial future. While delivering personal, day-to-day service focused on intricate details, your Private Client Relationship Manager will also assemble a team of CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNERTM professionals with objective advice, investment officers, and retirement specialists that meet your complex needs for the future. TO START EXPERIENCING THE EXCLUSIVE SERVICE YOU’VE EARNED, CALL 615-734-6165 Investments: Not A Deposit Not Guaranteed By The Bank Or Its Affiliates Not FDIC Insured Not Insured By Any Federal Government Agency May Go Down In Value Financial planning provided by First Tennessee Bank National Association (FTB). Investments available through First Tennessee Brokerage, Inc., member FINRA, SIPC, and a subsidiary of FTB. Banking products and services provided by First Tennessee Bank National Association. Member FDIC. ©2012 First Tennessee Bank National Association. www.firsttennessee.com Tires aren’T THE ONLY THing we’RE PASSIONATE ABOUT. BRIDGESTONEAMERICAS.com SUPPORTING THE ARTS IN NASHVILLE FOR OVER 20 YEARS. Letter from the Publishers Dear Readers, At a time when hard copy print publications are rapidly disappearing in favor of the ipad, iphone, kindle or whatever the next device may be that replaces print...it’s comforting to know that there are venues that exist where we still cherish the hard copy printed word. -

Miami Jazz & Film Society 2013 Jazz & Film Series

Miami Jazz & Film Society 2013 Jazz & Film Series JANUARY MAY SEPTEMBER (T) 1- The General | Safety Last | The Kid | The Circus | City Lights (T) 7- White Wedding | Story of a Three-Day Pass (T) 3- The Brother from Another Planet | Powder (Buster Keaton - Harold Lloyd - Charlie Chaplin silent films) (W) 8- Alice Day Band (Jazz) (T) 10- The Harder They Come | Music Is My Life, Politics My (T) 8- The Intouchables | Jo Jo Dancer (Richard Pryor) (T) 14- Baghdad Café | Border Café Mistress: The Story of Oscar Brown Jr. (W) 9- Yvonne Brown with Gary Thomas Trio (Jazz) (T) 21- Anne of Green Gables | Akeelah and the Bee (W) 11- Melton Mustafa Jr. (Jazz) (T) 15- King: A Man of Peace in a Time of War | Marley (T) 28- La Femme Nikita | Point of No Return (T) 17- Raising Arizona | The Straight Story (T) 22- Jean-Michel Basquiat | Purvis of Overtown (Th) 26- Biography of the Millennium: 100 People - 1000 Years (T) 29- Some Like it Hot | Almost Famous JUNE OCTOBER (T) 4- Where's Poppa? | Weekend at Bernie's (T) 1- The Temptress | Flesh and the Devil FEBRUARY (T) 11- Jazz: An American Story | The Cotton Club (Greta Garbo silent films) (T) 5- Lady be Good: Instrumental Women in Jazz (W) 12- Oriente (Jazz) (T) 8- The Five Heartbeats | What's Love Got to Do with it (T) 12- Mahogany | Camille (Greta Garbo) (T) 18- The Great Dictator | Lime Light (Charlie Chaplin) (W) 13- Yvonne Brown with Gary Thomas Trio (Jazz) (W) 9- Gary Thomas Quintet (Jazz) (T) 25- That's Dancing | The Red Shoes (T) 15- The Mysterious Lady | Garbo Archives (T) 19- The Goodbye Girl -

AMADEUS Previews Begin Wednesday, September 4

CONTACT: Nancy Richards – 917-873-6389 (cell) /[email protected] MEDIA PAGE: www.northcoastrep.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE: NORTH COAST REPERTORY THEATRE SELECTS TONY WINNING MASTERPIECE AMADEUS TO BEGIN SEASON 38 ON A ROUSING NOTE By Peter Shaffer Performances Beginning Wednesday, September 4, 2019 NOW EXTENDED TO OCTOBER 6TH Directed by Richard Baird Solana Beach, Calif. – With the glorious music of Mozart as a backdrop, Peter Shaffer’s AMADEUS assures North Coast Repertory Theatre of a grand start to Season 38. The Tony winner for Best Play weaves the fascinating tale of composers Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri. Told in a series of flashbacks laced with humor, intrigue and personal insight, AMADEUS examines two men – one consumed with jealousy; the other, blissfully unaware of his extraordinary gifts. Deemed “terrifically entertaining and highly theatrical” by The New York Times, this audience favorite deftly explores musical genius by a master playwright. Tickets are already going quickly, so order now. Richard Baird directs Tony Amendola,* Rafael Goldstein,* Kathryn Tkel,* Louis Lotorto,* Nick Kennedy, Andrew Oswald,*Andrew Barnicle,* Alice Sherman,* Christopher M. Williams,* and Leigh Ellen Akin in AMADEUS. The design team includes Marty Burnett (Scenic Design), Matthew Novotny (Lighting), Elisa Benzoni (Costumes), Philip Korth (Props) and Peter Herman (Hair and Wig Design). Aaron Rumley* is the Stage Manager. *The actor or stage manager appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association. For photos, go to www.northcoastrep.org/press. AMADEUS previews begin Wednesday, September 4. Opening Night on Saturday, September 7, at 8pm. A new Preview Matinee has been added on Friday, September 6 at 2pm and Wednesday, September 25 at 2pm.There will be a special talkback on Friday, September 13, with the cast and artistic director. -

TWELVE ANGRY MEN REGINALD ROSE (1920-2002) Was Born and Grew up in New York City

Table of Contents Title Page Copyright Page Introduction ACT I ACT II Furniture and Property List Lighting Plot Effects Plot FOR THE BEST IN PAPERBACKS, LOOK FOR THE TWELVE ANGRY MEN REGINALD ROSE (1920-2002) was born and grew up in New York City. After Pearl Harbor he enlisted, and served in the Philippines and Japan as a First Lieutenant until 1946. Writing since he was a teenager, he sold the first of his many television plays, The Bus to Nowhere, in 1950. He was called for jury duty for the first time in 1954. It was a manslaughter case and the jury argued bitterly for eight hours before bringing in a unanimous verdict. He decided this was a powerful situation on which to base a television play, and wrote Twelve Angry Men as a live one-hour drama for CBS’s Studio One. Its impact led to the film version in 1957, and he received Oscar nominations for Best Screenplay and Best Picture (as coproducer). The stage version was first produced in 1964, and revised versions in 1996 and 2004. In 1997 it was filmed for Showtime. Other TV plays include The Remarkable Incident at Carson Corners, Thunder on Sycamore Street, The Cruel Day, A Quiet Game of Cards, The Sacco-Vanzetti Story, Black Monday, Dear Friends, Studs Lonigan, The Rules of Marriage, and the award-winning Escape from Sobibor. Rose created, supervised, and wrote many of the episodes of the TV series The Defenders (1961-1965). His films include Crime in the Streets, Dino, Man of the West, The Man in the Net, Baxter!, Somebody Killed Her Husband, The Wild Geese, The Sea Wolves, and the film version of Whose Life Is It Anyway? He published Six Television Plays; The Thomas Book, written for children; and a memoir, Undelivered Mail. -

Kcstage-11-10.Pdf

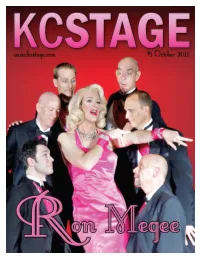

this halloween have guns. will rent. is your costume warehouse! Ask the Experts props + 9am-1pm Saturday, October 1 UMKC Solo & Small Firm Incubator, 4743 Troost accessories too! Non-profit Formation Workshop 6pm-8pm Thursday, November 17 Kansas City Artists Coalition, 201 Wyandotte . 1313 State Ave. Kansas City, have guns Kansas 66102 will rent. Phone: (913) 321-4867 Blog Notes www.kcstage.com/blog “Research: Art Works” Grants studies at UMKC. “Mastering the Screen- Grants are available in this new category play: Using Structure, Form and Imagery for research projects to analyze the value to Create a Successful Screenplay” is and impact of the arts in the US. Grants scheduled for November 19 from 12:30 generally range from $10,000 to $30,000 to 4:30 pm, and the workshop is $40 for and while they do not require matching members of the Writers Place, and $60 funds, applicants are expected to provide for nonmembers. More information can some cash or in-kind services in support be found at writersplace.org. of the project. The deadline is Nov 8. For COVER [CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT FRONT]: Damian more information, go to www.nea.gov/ Grants for School Buses grants/apply/Research/index.html. Blake, David Towery, Jeff Bell, Alan The Big Yellow School Bus Grant provides Tilson, Tim Taylor, David Schlumer, Ron up to $500 to help schools meet the trans- Megee in center. Photographer: Bob Amphitheater For Sale portation costs of educational field trips Compton. Hair and Makeup: Andrew An amphitheater located in Camdenton, to arts institutions and activities in Mis- Chambers. -

Twelve Angry Men

Twelve Angry Men by Reginald Rose 1 Leadership What is leadership? Who makes a good leader? What are the qualities of a strong leader? Here are several points to consider when reading the play and discussing leadership: 1. the ability to speak out, take a risk, act on one’s convictions 2. the ability to stand by oneself on an issue, even if there is no support 3. the ability to break from the crowd or be a role model for the crowd even if it is unpopular 4. the ability to act on, or voice, a concern on the behalf of others; being an advocate for others who may not have or feel they have a voice Add your own ideas about what makes a strong leader in the space below. 2 Twelve Angry Men “Courage” four corner exercise Respond as honestly as possible to the following statements by circling your response. 1. I work to solve problems without violence. SA A SD D 2. I work to solve problems with intimidation and threats. SA A SD D 3. I frequently cave in to peer pressure. SA A SD D 4. I seldom cave in to peer pressure. SA A SD D 5. I stand up for what is right even if I stand alone. SA A SD D 6. I prefer to have other people standing with me. SA A SD D 7. I am afraid to express myself just because other people might disapprove. SA A SD D 8. I do not hesitate to express my opinion even if it is unpopular. -

CABARET Is Produced by Arrangement with TAMS-WITMARK MUSIC LIBRARY, INC., 560 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY 10022

FLORIDA REPERTORY THEATRE 2017-2018 SEASON HISTORIC ARCADE THEATRE • FORT MYERS RIVER DISTRICT ROBERT CACIOPPO, PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PRESENTS SPONSORED BY CHIPPENDALE AUDIOLOGY STARRING BRITT MICHAEL GORDON* • JILLIAN LOUIS* • MICHAEL MAROTTA* JASON PARRISH*† • JACKIE SCHRAM* • GARY TROY* • LORI WILNER* and HALEY CLAY • HILLARY EKWALL* • DILLON FELDMAN • ALEXIS FISHMAN* • LEEDS HILL* • ANDREW HUBACHER* • LIAM HUTT • YSABEL JASA • VIRGINIA NEWSOME JULIA RIFINO • SEAN ROYAL DIRECTED BY STEPHANIE CARD** MUSIC DIRECTOR CHOREOGRAPHER SET DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER ALEX SHIELDS ARTHUR D’ALESSIO JORDAN MOORE STEFANIE GENDA*** ensemble member LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER/ENGINEER DIALECT COACH FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHER TYLER M. PERRY*** JOSH SCHACHT GREG LONGENHAGEN* KODY C. JONES ensemble member REHEARSAL STAGE MANAGER PERFORMANCE STAGE MANAGER ASST. STAGE MANAGERS JANINE WOCHNA* MOLLY BRAVERMAN* KASEY PHILLIPS* • LAURA WEST CABARET is produced by arrangement with TAMS-WITMARK MUSIC LIBRARY, INC., 560 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY 10022 2017-18 GRAND SEASON SPONSORS The Fred & Jean Allegretti Foundation • Naomi Bloom & Ron Wallace • Dinah Bloomhall • Jane & Bob Breisch Alexandra Bremner • Janet & Bruce Bunch • Chippendale Audiology • Berne Davis • Mary & Hugh Denison Ellie Fox • David Fritz/Cruise Everything • Nancy & Jim Garfield • Vici and Russ Hamm John Madden • Joel Magyar • Noreen Raney • Linda Sebastian & Guy Almeling • Arthur M. Zupko This entire season sponsored in part by the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs, and the Florida Council on Arts and Culture. Florida Repertory Theatre is a fully professional non-profit LOA/LORT Theatre company on contract with the Actors’ Equity Association that proudly employs members of the national theatrical labor unions. *Member of Actors’ Equity Association. **Member of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society.