The Meaning of South African Media's Expansion Into the Rest of African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Owns the News Media?

RESEARCH REPORT July 2016 WHO OWNS THE NEWS MEDIA? A study of the shareholding of South Africa’s major media companies ANALYSTS: Stuart Theobald, CFA Colin Anthony PhibionMakuwerere, CFA www.intellidex.co.za Who Owns the News Media ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We approached all of the major media companies in South Africa for assistance with information about their ownership. Many responded, and we are extremely grateful for their efforts. We also consulted with several academics regarding previous studies and are grateful to Tawana Kupe at Wits University for guidance in this regard. Finally, we are grateful to Times Media Group who provided a small budget to support the research time necessary for this project. The findings and conclusions of this project are entirely those of Intellidex. COPYRIGHT © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd This report is the intellectual property of Intellidex, but may be freely distributed and reproduced in this format without requiring permission from Intellidex. DISCLAIMER This report is based on analysis of public documents including annual reports, shareholder registers and media reports. It is also based on direct communication with the relevant companies. Intellidex believes that these sources are reliable, but makes no warranty whatsoever as to the accuracy of the data and cannot be held responsible for reliance on this data. DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS Intellidex has, or seeks to have, business relationships with the companies covered in this report. In particular, in the past year, Intellidex has undertaken work and received payment from, Times Media Group, Independent Newspapers, and Moneyweb. 2 www.intellidex.co.za © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd Who Owns the News Media CONTENTS 1. -

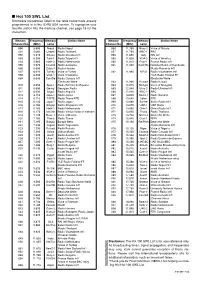

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

The Art of Pitching (2005) the Art of Co-Production the Art of Sourcing Content National and International Annual Observances Thought Memory

Producer Guide The PArti tofc hing Pitching A Handbook for Independent Producers 2013 Revised and Updated Published by the SABC Ltd as a service to the broadcast sector Pitch the act of presenting a proposal to a broadcaster – either in person or in the form of a document The word “pitch” became common practice in the early days of cinema when studios needed an expression of the passion that was not always evident in written words. “You write the words, but you pitch the feelings.” "If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together" - African proverb “A tree is known by its fruit” - Zulu proverb Content is Queen In this series The Art of Pitching (2005) The Art of Co-production The Art of Sourcing Content National and International Annual Observances Thought Memory © SABC Ltd 2013 Pitching The Art of PitchingPitching Revised Edition 2013 By Howard Thomas Commissioned by SABC Innovation and Editorial Conceptualised and initiated by Yvonne Kgame © SABC Ltd 2013 The Art of Pitching Howard Thomas has worked in the entertainment industry all his life, and in television since it first arrived in South Africa in 1976. He is an award-winning TV producer, and has worked in theatre, radio, films, magazines and digital media. He has been writing about the industry for over 20 years. He is also a respected trainer, lecturer and facilitator, columnist and SAQA accredited as an assessor and moderator. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by electrical or mechanical means, including any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. -

The South African Broadcasting Corporation’S (SABC) 2019/20 Annual Report Was Tabled in Parliament on Tuesday, 17 November 2020

MEDIA STATEMENT SABC TABLES 2019/20 ANNUAL REPORT Johannesburg, Tuesday, 17 November 2020 - The South African Broadcasting Corporation’s (SABC) 2019/20 Annual Report was tabled in Parliament on Tuesday, 17 November 2020. As detailed in the Annual Report, the public broadcaster continues to deliver on its extensive public service mandate despite very challenging conditions. While the Corporation faced another difficult year that was further compounded by depressed economic activities that particularly affected revenue generation, the public can be reassured that the building blocks to stabilise the Corporation are now in place. At the end of March 2020, the Corporation reported a net loss of R511 million, a 6% decline compared to the previous year, but a 20% better performance against budget. In a challenging economic environment, total revenue declined by 12% year-on-year to R5.7 billion. The decline can be attributed primarily to a decrease in advertising spend across the industry and the delay in finalising commercial partnerships on digital platforms. TV licence revenue has also come under pressure under difficult economic conditions for our audiences. TV licence revenue declined by 18% year-on-year to R791 million due the delayed use of Debt Collection Agencies in this period. This resulted in only 24% of the total licence fees billed being realised as revenue, compared to 31% for the year ended 31 March 2019. As part of an overall policy review, the SABC is currently finalising proposals to government on the future collection of a public broadcasting levy, taking into account differing public views on this issue as well as international best practice. -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence. -

The Development of a Business Model for a Community Radio Station

Developing a business model for a community radio station in Port Elizabeth: A case study. By Anthony Thamsanqa “Delite” Ngcezula Student no: 20531719 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Business Administration at the NMMU Business School Research supervisor: Dr Margaret Cullen November, 2008 DECLARATION BY STUDENT FULL NAME: Anthony Thamsanqa “Delite” Ngcezula STUDENT NUMBER: 20531719 QUALIFICATION: Masters in Business Administration DECLARATION: In accordance with Rule G4.6.3, I hereby declare that this treaties with a title “Developing a business model for a community radio station in Port Elizabeth: A case study” is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. SIGNITURE: __________________________ DATE: ________________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude and thanks to my research supervisor, Doctor Margaret Cullen, whose academic guidance and encouragement was invaluable. I wish to thank Kingfisher FM as without their cooperation this treatise would not have been possible. I would like to thank my wife, Spokazi for putting up with the long hours I spent researching and writing this treatise. I wish to thank my girls, Litha and Gcobisa for their unconditional love. I would like to thank my parents, Gladys and Wilson for the values they instilled in me. I wish to thank the following people who made listening to radio an experience and inspired my love for radio presenting and -

Analysis of SABC News and Programming Lack of Diversity (Repeat) Analysis of SABC News and Programming

Lack of Diversity (Repeat) Analysis of SABC News and Programming Lack of Diversity (Repeat) Analysis of SABC News and Programming Written by Lethabo Thebe Dibetso and Thandi Smith Edited by Wellington Radu, William Bird and Sandra Banjac Creative Commons Copyright Media Monitoring Africa 2012 Funded by: Quality and Diversity in SABC Content South Africa is a country rich in diversity and it is not only important that the SABC celebrates South Africa’s national identity and culture but also reflects South Africa’s diverse languages, cultures, and people in its programmes, as required by its mandate. This report assesses the quality and diversity of all SABC programming and news content across different mediums. Acknowledgements The successful completion of this project can be attributed to the project team consisting of Carol Netshifhefhe, Lethabo Thebe Dibetso, Thandi Smith, with the help of Wellington Radu, Sandra Roberts and Albert van Houten. Data was collected by Bradley Romersa, Musa Rikhotso, Nobantu Urbania Mkhwanazi, Silvia Matlala, Sandile Ndlangamandla and Uyanda Siyotula. Media Monitoring Africa would also like to acknowledge MMA’s Director, William Bird for his oversight of this research. We would also like to thank the Open Society Foundation for their support of this research report. i Table of Contents Table of Contents ii List of Figure iv Executive Summary vii 1. Introduction 1 2. SABC’s Commitments to Quality and Diversity 2 3. How the research was conducted 5 3.1 What do we mean by diversity and quality of programming and news? 5 3.1.1 How the schedule analysis was conducted 6 3.1.2 How the news was analysed 6 3.2 The criteria for news analysis 7 3.3 Research limitations 8 4. -

Towards the Transformation of the ZBC Into a Public Broadcaster

MISA-Zimbabwe MISA-Zimbabwe submissions on the need for the transformation of the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) into an independent public broadcasting service 1 Introduction Zimbabwe, being a member of such bodies as the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), is party to such documents as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Windhoek Declaration, the African Charter on Broadcasting and the SADC Protocol on Culture, Information and Sport. All these declarations require that signatory states respect basic human rights, especially freedom of expression, and in particular, they call for the creation of an enabling environment for media freedom, pluralism and diversity. Some of these declarations set minimum standards for the transformation of the state broadcasters into genuine public service broadcasters (PSBs) that are protected against political or commercial interference and whose programming serve the public interest. This paper seeks to advance the Media Institute of Southern Africa-Zimbabwe’s position on the need to transform the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) into a truly public service broadcasting (PSB) entity. To achieve this, the paper starts by giving a background to MISA and its activities, mission and values, as well as the organisation’s key programme areas. This is followed by defining the role of the media in society and a definition of the notion of PSB, as a way of providing some conceptual background. It is argued that PSB plays too crucial a role in the democratisation and development of a nation to be left to the whims of a Ministry which is only accountable to the Executive alone. -

Ideology and Myth in South African Television: a Critical Analysis of Sabc Channel Brand Identities

IDEOLOGY AND MYTH IN SOUTH AFRICAN TELEVISION: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF SABC CHANNEL BRAND IDENTITIES by WOUDRI BOTHA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium (Visual Studies) in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA May 2010 Supervisor: Prof Jeanne van Eeden © University of Pretoria DECLARATION Student number: 21284254 I declare that Ideology and myth in South African television: a critical analysis of SABC television channel brand identities is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ___________________________ ________________________ Ms W Botha Date ii “There are many different kinds of metaphors in which our thinking about cultural change takes place. These metaphors themselves change. Those which grip our imagination, and, for a time, govern our thinking about scenarios and possibilities of cultural transformation, give way to new metaphors, which make us think about these difficult questions in new terms” (Stuart Hall 1996f:287). iii SUMMARY Title: Ideology and myth in South African television: a critical analysis of SABC channel brand identities Name: Woudri Botha Supervisor: Prof Jeanne van Eeden Department: Department of Visual Arts Degree: Magister Artium (Visual Studies) Summary: This dissertation investigates the brand identities of the South African Broadcasting Corporation television channels SABC1, SABC2 and SABC3 during the first decade of the 2000s (from 2000 to 2009). The study explores the manifestation and dissemination of dominant political ideologies and myths by the SABC television channels and their respective brand identities. It is argued that SABC television channels are structured and organised according to specific brand ideologies that match dominant political ideologies prevalent in South Africa. -

Death by Policy

List of 33.305 documented deaths of refugees and migrants due to the restrictive policies of Fortress Europe Documentation as at 15 June 2017 by UNITED Death by Policy - Time for Change! Campaign information: Facebook - UNITED Against Refugee Deaths, UnitedAgainstRefugeeDeaths.eu, [email protected], Twitter: @UNITED__Network #AgainstRefugeeDeaths UNITED for Intercultural Action, European network against nationalism, racism, fascism and in support of migrants and refugees Postbus 413 NL-1000 AK Amsterdam phone +31-20-6834778, fax 31-20-6834582, [email protected], www.unitedagainstracism.org The UNITED List of Deaths can be freely re-used, translated and re-distributed, provided source (www.unitedagainstracism.org) is mentioned. Researchers can obtain this list with more data in xls format from UNITED. name region of origin cause of death source number found dead 29/05/2017 30 N.N. (1 small child) unknown 2 bodies found, 28 missing, drowned or trampled in panic, when boat sank off Libya VOA/USNews 27/05/2017 10 N.N. unknown drowned, during 24 hours of rescue operations between Libya and Italy, 2200 rescued DailySabah 24/05/2017 82 N.N. unknown missing, after falling into the water when their rubber boat deflated between Libya and Italy USNews 23/05/2017 34 N.N. (7 children, 13 women) unknown drowned, when boat of 500 suddenly capsized off Libya, sending 200 people into the sea DailyStar/USNews/Xinhua 22/05/2017 2 N.N. West Africa/unknown 1 drowned, 1 missing, in the Mediterranean Sea on the way to Italy IOM 22/05/2017 2 N.N. (men) unknown bodies found in Al Maya (Libya) IOM 19/05/2017 1 N.N. -

South Africa 2018/19 Communications

OFFICIAL GUIDE TO South Africa 2018/19 Communications 53 Official Guide to South Africa 2018/19 Communications 54 Department of Communications (DoC) and Digital Technologies (DCDT) Following the reconfiguration of government departments in June 2019, the DoC was merged with the Department of Telecommunications and Postal Services (DTPS) to form the new DCDT. The then DoC was spearheading the process of migrating broadcasting signals from analogue to digital. South Africa’s national digital network coverage comprises DTT transmission coverage of 84% of the population with the remaining 16% to be covered by satellite network. DTT is a reliable and cost-efficient means to distribute linear TV content and has many advantages over the analogue broadcasting system. One of its major advantages for communities is that it clears the analogue spectrum for the delivery of broadband mobile Internet and Wi-fi services. To view digital TV signals on an ordinary analogue TV set, consumers will need a set-top box (STB). Government will provide about five million poor TV-owning households with free STBs. Once the migration is complete, high definition TV telecast facilities would be available, along with expanded community, FM and satellite radio services to the entire population. During the 2017/18 financial year, the then DoC developed the White Paper on Audio-Visual and Digital Content Policy for South Africa, which provides enabling mechanisms to facilitate ownership of the new audio-visual digital content value chain by previously disadvantaged communities and small, medium and micro enterprises. Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) In 2018, Communications (and Digital Technologies) Minister Stella Ndabeni-Abrahams announced the “Building a Capable 4IR Army” capacity development programme to ensure that communities are equipped to take advantage of new digital technologies, unlock future jobs and drive competitiveness.