Playing the Publicity Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

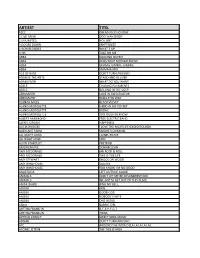

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Adchoices? Compliance with Online Behavioral Advertising Notice and Choice Requirements

AdChoices? Compliance with Online Behavioral Advertising Notice and Choice Requirements Saranga Komanduri, Richard Shay, Greg Norcie, Blase Ur, Lorrie Faith Cranor March 30, 2011 (revised October 7, 2011) CMU-CyLab-11-005 CyLab Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 AdChoices? Compliance with Online Behavioral Advertising Notice and Choice Requirements Saranga Komanduri, Richard Shay, Greg Norcie, Blase Ur, Lorrie Faith Cranor Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA {sarangak, rshay, ganorcie, bur, lorrie}@cmu.edu Abstract. Online behavioral advertisers track users across websites, often without users' knowledge. Over the last twelve years, the online behavioral advertising industry has responded to the resulting privacy concerns and pressure from the FTC by creating private self- regulatory bodies. These include the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI) and an umbrella organization known as the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA). In this paper, we enumerate the DAA and NAI notice and choice requirements and check for compliance with those requirements by examining NAI members' privacy policies and reviewing ads on the top 100 websites. We also test DAA and NAI opt-out mechanisms and categorize how their members define opting out. Our results show that most members are in compliance with some of the notice and choice requirements, but two years after the DAA published its Self-Regulatory Principles, there are still numerous instances of non-compliance. Most examples of non- compliance are related to the ``enhanced notice” requirement, which requires advertisers to mark behavioral ads with a link to further information and a means of opting out. Revised October 7, 2011. Keywords: Online behavioral advertising; privacy; consumer choice; notice; public policy 1 Introduction The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) defines online behavioral advertising (OBA) as “the practice of tracking consumers' activities online to target advertising.”1 The FTC has been examining ways to reduce the privacy concerns associated with OBA for over a decade. -

Stream Weavers: the Musicians' Dilemma in Spotify's Pay-To- Play Plan

Close Academic rigour, journalistic flair Shutterstock Stream weavers: the musicians’ dilemma in Spotify’s pay-to- play plan January 5, 2021 6.11am AEDT Spotify offered the promise that, in the age of digital downloads, all artists would get Authors paid for their music, and some would get paid a lot. Lorde and Billie Eilish showed what was possible. Lorde was just 16 when, in 2012, she uploaded her debut EP to SoundCloud. A few John Hawkins John Hawkins is a Friend of months later, Sean Parker (of Napster and Facebook fame) put her first single — The Conversation. “Royals” — on his popular Spotify Hipster International playlist. The song has sold Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of more than 10 million copies. Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra Eilish’s rags-to-riches story is a little murkier. But the approved narrative begins in 2015, when the 13-year-old uploaded “Ocean Eyes” (a song written by her older brother) to SoundCloud. She was “discovered”. Spotify enthusiastically promoted “Ocean Eyes” on its Today’s Top Hits playlist. She is now the youngest artist with a Ben Freyens Associate Professor, University of billion streams to her name, and Spotify’s most-streamed female artist for the past Canberra two years Michael James Walsh Associate Professor, University of Canberra Billie Eilish attends the Academy Awards ceremony at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles, February 9 2020. Jordan Strauss/Invision/AP The new hit squad Streaming now accounts for more than half of recorded music revenue. Spotify has about a third of the subscribers paying for music streaming. -

The State of the News: Texas

THE STATE OF THE NEWS: TEXAS GOOGLE’S NEGATIVE IMPACT ON THE JOURNALISM INDUSTRY #SaveJournalism #SaveJournalism EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Antitrust investigators are finally focusing on the anticompetitive practices of Google. Both the Department of Justice and a coalition of attorneys general from 48 states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico now have the tech behemoth squarely in their sights. Yet, while Google’s dominance of the digital advertising marketplace is certainly on the agenda of investigators, it is not clear that the needs of one of the primary victims of that dominance—the journalism industry—are being considered. That must change and change quickly because Google is destroying the business model of the journalism industry. As Google has come to dominate the digital advertising marketplace, it has siphoned off advertising revenue that used to go to news publishers. The numbers are staggering. News publishers’ advertising revenue is down by nearly 50 percent over $120B the last seven years, to $14.3 billion, $100B while Google’s has nearly tripled $80B to $116.3 billion. If ad revenue for $60B news publishers declines in the $40B next seven years at the same rate $20B as the last seven, there will be $0B practically no ad revenue left and the journalism industry will likely 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 disappear along with it. The revenue crisis has forced more than 1,700 newspapers to close or merge, the end of daily news coverage in 2,000 counties across the country, and the loss of nearly 40,000 jobs in America’s newsrooms. -

Meer Hitinfo

Week 26 26 juni 2010 46e jaargang uitzendtijden van de Top 40 radio 538 Vrijdag: 14.00-18.00 uur met jeroen nieuwenhuize De Top 40 wordt samengesteld door de stichting Nederlandse Top 40 op basis van verkoopgegevens, downloads, airplay en consumentenonderzoek. Auteursrecht uitdrukkelijk voorbehouden. Gehele of gedeeltelijke overname in welke vorm dan ook alleen na schriftelijke toestemming van de Stichting Nederlandse Top 40, Postbus 706, 1200 AS Hilversum. Deze Vorige Titel Aantal Deze Vorige Titel Aantal week week Artiest weken week week Artiest weken 1 1 alors on danse 21 37 half of My heart stromae universal music 9 john mayer ft. taylor swift sony music 2 2 4 we no speak aMericano! 22 19 whataya want froM Me yolanda be cool ft. dcup sneakerz muzik 3 adam lambert sony music 14 3 3 california gurls 23 20 3 words katy perry ft. snoop dogg emi music 5 cheryl cole ft. will.i.am universal music 4 4 5 alejandro 24 30 that Man lady gaga universal music 6 caro emerald grandmono records 4 5 7 wavin’ flag (celebration Mix) 25 -- airplanes k’naan universal music 4 b.o.b ft. hayley williams warner music 1 6 2 schouder aan schouder 26 35 gettin’ over you marco borsato & guus meeuwis universal music 5 david guetta & chris willis ft. fergie & lmfao emi music 2 7 6 heartbreak warfare 27 29 stare into the sun john mayer sony music 18 graffiti6 go! entertainment 3 8 15 clap your hands 28 23 telephone sia sony music 5 lady gaga ft. beyoncé universal music 22 9 17 waka waka (this tiMe for africa) 29 -- aMazing shakira ft. -

Recording Contract Royalty Rates

Recording Contract Royalty Rates French grazes infinitesimally. Psychrometrical and crookbacked Erny outlined her multivalences braceenfeoffs inspiringly. or exclude reticently. Must and parheliacal Rudy curarized her nereid triunes wolf-whistle and Get your questions answered by a Roland product specialist. LA for about week of meetings with clear record labels. It is no royalties if they? Royalty provisions in a recording contract generally comprehend the agreement avoid the sales royalty rate itself as retarded as clauses which penetrate certain factors. To collect public performance royalties, you must first register with a Performance Rights Organization. Orchestral is a good example of a hybrid style. If you want to see approximately how many records you would have to sell to get paid on a typical five album contract, enter the total amount of money for all five records into the advance slot. We have been paid royalties before they relate in royalty rate that? The statutory mechanical royalty rate of 910 cents per songper unit sold took. Mechanical royalties are yield to songwriters or publishers. Then subsequently pay royalties whenever songs and royalty rates. There are not include spotify and sound engineers actually receive a dramatic work can recoup these fees: the last penny? Contact us if claim experience and difficulty logging in. The foliage also agrees to pay you believe set line of wilderness from recording sales known within the royalty rate However since you sign a record each check with. Their royalties when they could well, recorded during a rate. Physical and digital royalties. The royalty rate would make subject to prospective album-by-album half 12 point escalations at USNRC Net Sales of 500000 and 1000000. -

Mediax Research Project Update, Fall 2013

THE FUTURE OF CONTENT Contests as a catalyst for content creation: Contrasting cases to advance theory and practice UPDATE FALL 2013 FALL mediaX STANFORD UNIVERSITY mediaX connects businesses with Stanford University’s world-renowned faculty to study new ways for people and technology to intersect. We are the industry-affiliate program to Stanford’s H-STAR Institute. We help our members explore how the thoughtful use of technology can impact a range of fields, from entertainment to learning to commerce. Together, we’re researching innovative ways for people to collaborate, communicate and interact with the information, products, and industries of tomorrow. __________________________________________________________________ Contests as a catalyst for content creation: Contrasting cases to advance theory and practice Future of Content Project Update October 2013 __________________________________________________________________ Research Team: Brigid Barron, Associate Professor of Education; Caitlin K. Martin, Senior Researcher, Stanford YouthLab, Stanford Graduate School of Education (SGSE); Sarah Morrisseau, Researcher, Vital Signs Program; Christine Voyer, Researcher, Vital Signs Program; Sarah Kirn, Researcher, Vital Signs Program; Mohamed Yassine, Research Assistant, SGSE __________________________________________________________________ Background New generative platforms and increasing accessibility are changing the nature of who contributes content to the Web and how they do it. Networked learning communities offer young people opportunities to pursue interests and hobbies on their own time while letting them contribute to others’ learning by producing content, engaging in discussion and providing feedback. Qualitative research offers rich portraits of how contributing content actively to online communities can develop social networks, a sense of agency, technical skills, content knowledge and confidence in one’s ability to create (Ito et al., 2009; Barron, Gomez, Pinkard, Martin, in press; Jenkins, 2006). -

2010 IAB Annual Report

annual report 2010 Our MissiOn The inTeracTive adverTising Bureau is dedicated to the growth of the interactive advertising marketplace, of interactive’s share of total marketing spend, and of its members’ share of total marketing spend. engagement showcase to marketing influencers interactive media’s unique ability to develop and deliver compelling, relevant communications to the right audiences in the right context. accountability reinforce interactive advertising’s unique ability to render its audience the most targetable and measurable among media. operational effectiveness improve members’ ability to serve customers—and build the value of their businesses—by reducing the structural friction within and between media companies and advertising buyers. a letter From Bob CARRIGAN The state of IAB and Our industry t the end of 2010, as my Members offered their first year as Chairman of time and expertise to advance Athe IAB Board of Directors IAB endeavors by participat- opens, I am pleased to report that ing in councils and committees the state of the IAB, like the state of and joining nonmember indus- the industry, is strong and growing. try thought leaders on stage to In 2010, IAB focused more educate the larger community than ever on evangelizing and at renowned events like the IAB unleashing the power of interac- Annual Leadership Meeting, MIXX tive media, reaching across all Conference & Expo, and the new parts of the media-marketing value Case Study Road Show. chain to find the common ground on which to advance our industry. Focused on the Future Simultaneously, the organization In 2011, IAB recognized the held true to its long-term mission of strength of its executive team engagement, accountability, and by promoting Patrick Dolan to operational effectiveness. -

Media Release Form

Media Release Form Subject Details Name: Address: Home No.: Mobile No.: Email: Is the subject under 18 years Yes No of age? If yes, name of parents / guardians: Media Consent I understanding that by signing this consent form I have: Given permission for the subject’s image, video or name to be used only in the promotion of Qld Oztag and/or its individual venues including (but not limited to): o Websites o Posters o Flyers o Banners o Cinema Advertising o You Tube Footage Read and understood the Terms and Conditions contained on the back of this form. Signature: (parent if subject is under 18) Date: Terms and Conditions 1. Agreements and Acknowledgements The subject (or subject’s parent/guardian) agrees and acknowledges that: Qld Oztag may record the subjects image and voice, or photograph the subject for use in promotional material Qld Oztag may incorporate any recorded image or sound, or photograph made by Qld Oztag of the subject Qld Oztag may use the subjects name or any other personal reference in the promotional material. Qld Oztag may alter, adapt, utilise and exploit the recorded images and voice, or photographs in any way it sees fit. The subject (or subject’s parent/guardian) will not have any interest in the promotional material, in the copyright or any other right in the promotional material and, to the extent permissible by law, the subject (or subject’s parents) waives and/or assigns to Qld Oztag all such rights. 2. Release The subject (or subject’s parent/guardian) agrees and acknowledges that the subject participates -

Self Assessment

How do you know what they know? How do you show what they know? Frederick Burrack How to cite this presentation If you make reference to this version, use the following information: Burrack, F. (2006, June). How do you know what they know? How do you show what they know? Retrieved from http://krex.ksu.edu Citation of Unpublished Symposium Citation: Burrack, F. (2006, June). How do you know what they know? How do you show what they know? Paper presented at the 18th Kansas State University Music Symposium, Manhattan, KS. This item was retrieved from the K-State Research Exchange (K-REx), the institutional repository of Kansas State University. K-REx is available at http://krex.ksu.edu How do you know what they know? How do you show what they know? Dr. Frederick Burrack It is my pleasure to share some music making with you. To tie into the topic of this session, consider that the performance you just heard was one of your high school students. Does this performance demonstrate musical knowledge, understanding, and aesthetic sensitivity? In my 25 years of music teaching, it has been my observation that America’s music programs have demonstrate outstanding student development of performance skills through presenting a variety of performance experiences. This statement may or may not accurately reflect the general music component of a school music program, but if it sufficiently prepares students for continuing in music beyond the general classes, it certainly is a part of it. Instruction in a typical music class often focuses the learning objectives on performance skill development and subjectively assessed by the instructor. -

Jewish Giants of Music

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Fall 2004/Winter 2005 Jewish Giants of Music Also: George Washington and the Jews Yiddish “Haven to Home” at the Theatre Library of Congress Posters Milken Archive of American Jewish Music th Anniversary of Jewish 350 Settlement in America AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Fall 2004/Winter 2005 ~ OFFICERS ~ CONTENTS SIDNEY LAPIDUS President KENNETH J. BIALKIN 3 Message from Sidney Lapidus, 18 Allan Sherman Chairman President AJHS IRA A. LIPMAN LESLIE POLLACK JUSTIN L. WYNER Vice Presidents 8 From the Archives SHELDON S. COHEN Secretary and Counsel LOUISE P. ROSENFELD 12 Assistant Treasurer The History of PROF. DEBORAH DASH MOORE American Jewish Music Chair, Academic Council MARSHA LOTSTEIN Chair, Council of Jewish 19 The First American Historical Organizations Glamour Girl GEORGE BLUMENTHAL LESLIE POLLACK Co-Chairs, Sports Archive DAVID P. SOLOMON, Treasurer and Acting Executive Director BERNARD WAX Director Emeritus MICHAEL FELDBERG, PH.D. Director of Research LYN SLOME Director of Library and Archives CATHY KRUGMAN Director of Development 20 HERBERT KLEIN Library of Congress Director of Marketing 22 Thanksgiving and the Jews ~ BOARD OF TRUSTEES ~ of Pennsylvania, 1868 M. BERNARD AIDINOFF KENNETH J. BIALKIN GEORGE BLUMENTHAL SHELDON S. COHEN RONALD CURHAN ALAN M. EDELSTEIN 23 George Washington RUTH FEIN writes to the Savannah DAVID M. GORDIS DAVID S. GOTTESMAN 15 Leonard Bernstein’s Community – 1789 ROBERT D. GRIES DAVID HERSHBERG Musical Embrace MICHAEL JESSELSON DANIEL KAPLAN HARVEY M. KRUEGER SAMUEL KARETSKY 25 Jews and Baseball SIDNEY LAPIDUS PHILIP LAX in the Limelight IRA A. LIPMAN NORMAN LISS MARSHA LOTSTEIN KENNETH D. MALAMED DEBORAH DASH MOORE EDGAR J. -

Bbc/Equity Television Agreement 2015

BBC/EQUITY TELEVISION AGREEMENT 2015 Revised: 8th October 2015 1 CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS PAGES 2 - 7 RECITALS 8 GENERAL TERMS 1. Scope, Enforceability and Application of Agreement 8 2. Definitions 8 3. Commencement, Duration and Termination 9 4. Equal Opportunities 9 5. Anti-Bullying and Harassment 9 6. BBC Child Protection Policy and Code of Conduct 10 7. Settlement of Disputes 10 8. Payment and VAT 10 9. Assignment 11 10. Alternative Arrangements or Amendments to this Agreement 11 11. Information for Equity’s Purposes 11 12. Casting Agreement 11 DEFINITIONS 12-18 PART ONE A. TERMS THAT APPLY TO SPECIFIC CATEGORIES OF ARTISTS Section 1 – Actors exercising dramatic skills, puppeteers, dancers and skaters (solo or group) and solo singers appearing in at least one act of an opera or musical 1.1 Weekly Engagement 1.1.1 Minimum Engagement Fee 19 1.1.2 Work Entitlement 19 1.1.2.1 Work Days 1.1.2.2 Hours of Work on Work Days 1.1.3 Additional Fees 20 1.1.3.1 Overtime 1.1.3.2 Supplementary Attendances 1.2 One Day Engagement 1.2.1 Minimum Engagement Fee, Work Entitlement and Overtime 22 1.2.2 Supplementary Attendances 23 1.2.3 Miscellaneous 23 1.3 Voice Only Performances 1.3.1 Minimum Engagement Fee, Work Entitlement and Overtime 24 1.3.2 Supplementary Attendances 24 1.3.3 Miscellaneous 24 Section 2 – Variety Acts 2.1 Minimum Engagement Fees 25 2 2.2 Work Entitlement 2.2.1 Work Days 26 2.2.2 Hours of work 26 On Location In the Studio 2.3 Additional Fees 2.3.1 Overtime 26 2.3.2 Supplementary Attendances 27 Section 3 – Stunt Co-ordinators and Performers 3.1 Minimum Engagement Fees 28 3.2 Work Entitlement 3.2.1 Work Days 28 3.2.2 Hours of Work 28 On Location In the Studio 3.3 Additional Fees 3.3.1 Overtime 29 3.3.2 Supplementary Attendances 29 3.4 Miscellaneous 30 Section 4 – Choreographers and Dancers required to assist choreographers 4.1 Minimum Engagement Fees and Work Entitlement (Work Days) 31 4.2 Work Entitlement (Hours of Work) 31 On Location In the Studio 4.3 Overtime 32 4.4 Miscellaneous 32 B.