1. History New.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enver Hoxhas Styre, Men Blev Samtidig Overvåget, Hvilket Shaban Sinani Har Dokumenteret

Kadaré-links • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Kadare-WIKI-060905.pdf • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Om-Ufuldendt-April.pdf • http://bjoerna.net/Agolli/Agolli-WIKI-060906.pdf • http://bjoerna.net/Agolli/artikler.pdf • http://bjoerna.net/Agolli/TT-interview-2006.pdf • http://bjoerna.dk/kort/Albanien.gif • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Hoxha-WIKI-060904.pdf • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Shehu-WIKI-060904.pdf • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/ALB-1946-01-11.jpg • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/ALB-1946-01-11-udsnit.jpg • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Dossier-K-b.jpg • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Sinani-2004.pdf • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Shehu.jpg • http://bjoerna.dk/dokumentation/Hoxha-on-Shehu.htm • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/ALB-Alia-Hoxha-1982-11-10.jpg • http://miqesia.dk/erfaring/albaniens_historie.htm • http://miqesia.dk/erfaring/Europa-Parlamentet-Albanien-1985.pdf • http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2000/03/jarvis.htm • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/1-5-1981.jpg • http://www.randomhouse.ca/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780385662529 • http://www.mahler.suite.dk/frx/euripides/bacchus_start_side.htm • http://www.albanianliterature.com/authors3/AA3-15poetry.html • http://www.elsie.de/ • http://www.complete-review.com/quarterly/vol6/issue2/bellos.htm http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Kadare-links.htm (1 of 2)09-10-2006 10:47:54 Kadaré-links • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/1977-1a.jpg • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/1977-2a.jpg • http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/ALB-Alia-Hoxha-1982-11-10.jpg http://bjoerna.net/Kadare/Kadare-links.htm (2 of 2)09-10-2006 10:47:54 Ismail Kadaré - Wikipedia 1/ 3 Ismail Kadaré Fra Wikipedia, den frie encyklopædi Ismail Kadaré (også stavet Ismaïl Kadaré eller Ismail Kadare), f. -

2 Marsi, Shansi I Fundit I Ilir Metës Të “Eliminojë” Bashën Dhe Të Marrë

Rr.Sitki Çiço përballë Maternitetit të Ri, Tel: 067 60 00 172, E-mail: [email protected] Reforma zgjedhore në rrezik, Ç ë m k imi 20 le opozita kërkon amnisti nga vetingu për anëtarët e Kolegjit E Premte 21 Shkurt 2020 Zgjedhor, socialistët dalin kundër Faqe 9 Lëkunden pozitat e Saimir Tahirit, dosja e ish-ministrit 2 marsi, shansi i fundit i Ilir Metës në dorë të gjyqtareve që kanë kaluar vetingun, të “eliminojë” Bashën dhe të marrë ja çfarë pritet nga Apeli Saimir Tahiri është politikani i parë, i cili do të përballet zyrtarisht me Strukturën e Posaçme Antikorrupsion. Edhe pse Prokuroria e Posaçme ka frenat e opozitës, Berisha skenar në dorë disa dosje korrupsioni, goditja e parë do të bëhet nga Gjykata e Posaçme e Apelit. Në shtator të vitit 2019, Gjykata e Shkallës... Faqe 6 djallëzor kundër pasardhësit Korrupsioni fut në kolaps Faqe 2-5 gjykatat e Apelit, vetëm 61 gjyqtarë mbeten në detyrë, KLGJ jep alarmin pas shkarkimeve të vetingut Pas Gjykatës Kushtetuese dhe Gjykatës së Lartë, drejt kolapsit pritet të shkojnë edhe gjykatat e Apelit. Alarmi është dhënë nga Këshilli i Lartë Gjyqësor, ku përmes një shkrese i është drejtuar ministres së Drejtësisë, Etilda Gjonaj dhe për dijeni edhe Kuvendit, qeverisë, Komisionit... Faqe 8 Skandalet me legalizimet, KLSH kallëzon penalisht 10 ish-funksionarë të ALUIZN-it në Tiranë dhe Bulqizë Vijojnë skandalet me legalizimet, pas Beratit dhe Lezhës që ishin pak ditë më parë këtë herë KLSH ka gjetur shkelje në dy qytete të tjera. Kontrolli i Lartë i Shtetit ka kallëzuar penalisht 10 ish-funksionarë të ALUIZN-it në Tiranë dhe Fatos Klosi dhe Petro Koçi: Rëndohet gjendja psikologjike Bulqizë. -

Albanian Catholic Bulletin Buletini Katholik Shqiptar

ISSN 0272 -7250 ALBANIAN CATHOLIC BULLETIN PUBLISHED PERIODICALLY BY THE ALBANIAN CATHOLIC INFORMATION CENTER Vol.3, No. 1&2 P.O. BOX 1217, SANTA CLARA, CA 95053, U.S.A. 1982 BULETINI d^M. jpu. &CU& #*- <gP KATHOLIK Mother Teresa's message to all Albanians SHQIPTAR San Francisco, June 4, 1982 ALBANIAN CATHOLIC PUBLISHING COUNCIL: ZEF V. NEKAJ, JAK GARDIN, S.J., PJETER PAL VANI, NDOC KELMENDI, S.J., BAR BULLETIN BARA KAY (Assoc. Editor), PALOK PLAKU, RAYMOND FROST (Assoc. Editor), GJON SINISHTA (Editor), JULIO FERNANDEZ Volume III No.l&2 1982 (Secretary), and LEO GABRIEL NEAL, O.F.M., CONV. (President). In the past our Bulletin (and other material of information, in cluding the book "The Fulfilled Promise" about religious perse This issue has been prepared with the help of: STELLA PILGRIM, TENNANT C. cution in Albania) has been sent free to a considerable number WRIGHT, S.J., DAVE PREVITALE, JAMES of people, institutions and organizations in the U.S. and abroad. TORRENS, S.J., Sr. HENRY JOSEPH and Not affiliated with any Church or other religious or political or DANIEL GERMANN, S.J. ganization, we depend entirely on your donations and gifts. Please help us to continue this apostolate on behalf of the op pressed Albanians. STRANGERS ARE FRIENDS News, articles and photos of general interest, 100-1200 words WE HAVEN'T MET of length, on religious, cultural, historical and political topics about Albania and its people, may be submitted for considera tion. No payments are made for the published material. God knows Please enclose self-addressed envelope for return. -

Honor Crimes of Women in Albanian Society Boundary Discourses On

HONOR CRIMES OF WOMEN IN ALBANIAN SOCIETY BOUNDARY DISCOURSES ON “VIOLENT” CULTURE AND TRADITIONS By Armela Xhaho Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies Supervisor: Professor Andrea Krizsan Second Reader: Professor Eva Fodor CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2011 Abstract In this thesis, I explore perceptions of two generations of men on the phenomenon of honor crimes of women in Albanian society, by analyzing in particular discourses on cultural and regional boundaries in terms of factors that perpetuate crimes in the name of honor. I draw on the findings from 24 in depth interviews, respectively 17 interviews with two generations of men who have migrated from remote villages of northern and southern Albania into periphery areas of Tirana and 7 interviews with representatives of key institutional authorities working in the respective communities. The conclusions reached in this study based on the perceptions of two generations of men in Albania suggest that, the ongoing regional discourses on honor crimes of women in Albanian society are still articulated by the majority of informants in terms of “violent” and “backward” cultural traditions, by exonerating the perpetrators and blaming the northern culture for perpetuating such crimes. However, I argue that the narrow construction on cultural understanding of honor crimes of women fails to acknowledge the gendered aspect of violence against women as a universal problem of women’s human rights across different cultures. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to acknowledge my supervisor Professor Andrea Krizsan for all her advices and helpful comments during the whole period of thesis writing. -

90 Vjet Kontrolli I Lartë I Shtetit

KALIOPI NASKA BUJAR LESKAJ 1925 KLSH 902015 90 VJET KONTROLLI I LARTË I SHTETIT Tiranë, 2015 Prof. dr. Kaliopi Naska Dr. Bujar Leskaj 90 Vjet Kontrolli i Lartë i Shtetit 1925 - 2015 Tiranë, 2015 1 Ky album është përgatitur në kuadrin e 90 vjetorit të Kontrollit të Lartë të Shtetit Autorë: Prof. dr. Kaliopi Naska Dr. Bujar Leskaj Arti grafik: DafinaKopertina: Stojko Kozma Kondakçiu Tonin Vuksani © Copyright: Kontrolli i Lartë i Shtetit Seria: botime KLSH - 16/2015/51 ISBN: 978-9928-159-41-0 Shtypur në shtypshkronjën: “Classic PRINT” Printing & Publishing Home Tiranë, 2015 2 SHPALLJA E PAVARËSISË DHE ELEMENTË TË KËSHILLIT KONTROLLUES 1912 – 1924 Qeveria e Vlorës dhe fillesat e Këshillit Kontrollues Akti i Shpalljes së Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë. Vlorë 28 nëntor 1912 Ismail Qemal Vlora Themelues i Shtetit Shqiptar Ismail Qemali duke përshëndetur popullin e Vlorës, në ceremoninë e 1-vjetorit të Pavarësisë, Vlorë 2013 Më 28 nëntor 1912 në mbledhjen e parë t i të Kuvendit Kombëtar të Vlorës u nënshkrua nga t e t delegatët Deklarata e Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë. h S i ë rt 90 vjet Kontrolli i La 3 Delegatët e Kuvendit të Vlorës Firmëtarët e Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë: Ismail Kemal Beu, Ilias bej Vrioni, Hajredin bej Cakrani, Xhelal bej Skrapari (Koprencka), Dud (Jorgji) Karbunara, Taq (Dhimitër) Tutulani, Myfti Vehbi Efendiu (Agolli), Abas Efendi (Çelkupa), Mustafa Agai (Hanxhiu), Dom Nikoll Kaçorri, Shefqet bej Daiu, Lef Nosi, Qemal Beu (Karaosmani), Midhat bej Frashëri, Veli Efendiu (Harçi), Elmas Efendiu (Boce), Rexhep Beu (Mitrovica), Bedri Beu (Pejani), Salih Xhuka (Gjuka), Abdi bej Toptani, Mustafa Asim Efendiu (Kruja), Kemal Beu (Mullaj), Ferid bej Vokopola, Nebi Efendi Sefa (Lushnja), Zyhdi Beu (Ohri), Dr. -

National Report on the Follow-Up to the Regional Implementation

National Report on the Follow-Up to the Regional Implementation Strategy (RIS) of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (MIPAA) in Albania during the period 2012-16 Executive summary Approximately 500 to 700 words (1-1.5 A4 pages, single-spaced). Please provide an executive summary according to the structure below: Methods used for this report; in particular, details of the bottom-up participatory approach used, if any Brief review of national progress in fulfilling (or lagging behind) the commitments of MIPAA/RIS. Include three to five major achievements since 2012 and three to five important aspects to be improved in the future Conclusion. This is the second report of Albania on regard of Madrid Plan on Ageing. For the first time, it is assured a high degree of participation from diverse sources and actors. Besides, using a number of reports, studies and analyses on ageing, produced since 2012 more than 20 stakeholders were invited to contribute with their information and experiences about progress and challenges during implementation of MIPAA/RIS. The instrument for stakeholders prepared by UNECE secretariat was translated into Albanian and discussed in two meetings with all relevant actors; one meeting dedicated to ministries and other state institutions and the other to non-governmental organizations. Albanian population ageing is characterized by relatively late demographic transition and high emigration rate. Albania has been acting in many areas since the Vienna Conference and its government has put ageing issues into its main priorities. A good example of it is the mainstreaming of ageing issues into the principal political document of the country such as strategy for development and integration 2015-2020, as well as, in the new Social Inclusion Policy Document 2016-2020. -

Albania=Schipetaria=Shqiperia= Shqipnija

ALBANIA ALBANIA=SCHIPETARIA=SHQIPERIA= SHQIPNIJA Republika e Shqiperise Repubblica d’Albania Tirane=Tirana 200.000 ab. (Valona fu capitale dal 1912 al 1920) Kmq. 28.748 (28.749)(28.750) Rivendica il Cossovo=Kossovo Rivendica alla GRECIA l’Epiro Meridionale Rivendica al MONTENEGRO: Malesja, area di Tuzi, Plav e Rozaje Rivendica alcuni territori alla MACEDONIA Dispute per le acque territoriali con MONTENEGRO Dispute per le acque territoriali con GRECIA Compreso Isola SASENO=SASAN (6 Kmq.) Compreso acque interne (Kmq. 1.350 – 5%) Movimento indip. in Nord Epiro=Albania Meridionale (minoranza greca) Movimento indip. in Illiria=Illyrida=Repubblica d’Illiria (con altri territori della Macedonia) Movimento indip. macedo-albanese Ab. 2.350.000---3.600.000 Densità 103 Popolazione urbana 39% Incremento demografico annuo 0,9% Coefficiente di natalità 24% Coefficiente di mortalità 5,4% Coefficiente di mortalità infantile 4,4%° Durata vita media 69 anni U. – 72 anni D. Età media 26 anni (35% >14 anni – 9% >60 anni) LINGUA Ufficiale/Nazionale Tosco=Tosk=Albanese Tosco=Albanian Tosk Ciechi 2.000 Sordi 205.000 Indice di diversità 0,26 Ghego=Albanese Ghego=Ghego Albanese=Albanian Gheg=Gego=Geg=Gheg=Sciopni=Shopni= Gheghe=Guegue (300.000) - Mandrica - Scippe=Ship=Cosovo=Cosovaro=Cossovo=Cossovaro=Kosove - Scutari=Shkoder - Elbasani=Elbasan=Elbasan-Tirana=Elbasan-Tirane=Tirana=Tirane Greco (60.000) Macedone=Slavico=Slavic=Slavico Macedone=Macedone Slavico=Macedonian Slavic (30.000) Romani Vlax=Vlax Romani (60.000) - Romani Vlax Meridionale=Southern Vlax -

Ligjvënësit Shqipëtarë Në Vite

LIGJVËNËSIT SHQIPTARË NË VITE Viti 1920 Këshilli Kombëtar i Lushnjës (Senati) Një dhomë, 37 deputetë 27 mars 1920–20 dhjetor 1920 Zgjedhjet u mbajtën më 31 janar 1920. Xhemal NAIPI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1920) Dhimitër KACIMBRA Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1920) Lista emërore e senatorëve 1. Abdurrahman Mati 22. Myqerem HAMZARAJ 2. Adem GJINISHI 23. Mytesim KËLLIÇI 3. Adem PEQINI 24. Neki RULI 4. Ahmet RESULI 25. Osman LITA 5. Bajram bej CURRI 26. Qani DISHNICA 6. Bektash CAKRANI 27. Qazim DURMISHI 7. Beqir bej RUSI 28. Qazim KOCULI 8. Dine bej DIBRA 29. Ramiz DACI 9. Dine DEMA 30. Rexhep MITROVICA 10. Dino bej MASHLARA 31. Sabri bej HAFIZ 11. Dhimitër KACIMBRA 32. Sadullah bej TEPELENA 12. Fazlli FRASHËRI 33. Sejfi VLLAMASI 13. Gjergj KOLECI 34. Spiro Jorgo KOLEKA 14. Halim bej ÇELA 35. Spiro PAPA 15. Hilë MOSI 36. Shefqet VËRLACI 16. Hysein VRIONI 37. Thanas ÇIKOZI 17. Irfan bej OHRI 38. Veli bej KRUJA 18. Kiço KOÇI 39. Visarion XHUVANI 19. Kolë THAÇI 40. Xhemal NAIPI 20. Kostaq (Koço) KOTA 41. Xhemal SHKODRA 21. Llambi GOXHAMANI 42. Ymer bej SHIJAKU Viti 1921 Këshilli Kombëtar/Parlamenti Një dhomë, 78 deputetë 21 prill 1921–30 shtator 1923 Zgjedhjet u mbajtën më 5 prill 1921. Pandeli EVANGJELI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1921) Eshref FRASHËRI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1922–1923) 1 Lista emërore e deputetëve të Këshillit Kombëtar (Lista pasqyron edhe ndryshimet e bëra gjatë legjislaturës.) 1. Abdyl SULA 49. Mehdi FRASHËRI 2. Agathokli GJITONI 50. Mehmet PENGILI 3. Ahmet HASTOPALLI 51. Mehmet PILKU 4. Ahmet RESULI 52. Mithat FRASHËRI 5. -

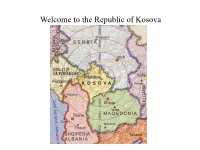

UNIVERSITY of PRISHTINA the University-History

Welcome to the Republic of Kosova UNIVERSITY OF PRISHTINA The University-History • The University of Prishtina was founded by the Law on the Foundation of the University of Prishtina, which was passed by the Assembly of the Socialist Province of Kosova on 18 November 1969. • The foundation of the University of Prishtina was a historical event for Kosova’s population, and especially for the Albanian nation. The Foundation Assembly of the University of Prishtina was held on 13 February 1970. • Two days later, on 15 February 1970 the Ceremonial Meeting of the Assembly was held in which the 15 February was proclaimed The Day of the University of Prishtina. • The University of Prishtina (UP), similar to other universities in the world, conveys unique responsibilities in professional training and research guidance, which are determinant for the development of the industry and trade, infra-structure, and society. • UP has started in 2001 the reforming of all academic levels in accordance with the Bologna Declaration, aiming the integration into the European Higher Education System. Facts and Figures 17 Faculties Bachelor studies – 38533 students Master studies – 10047 students PhD studies – 152 students ____________________________ Total number of students: 48732 Total number of academic staff: 1021 Visiting professors: 885 Total number of teaching assistants: 396 Administrative staff: 399 Goals • Internationalization • Integration of Kosova HE in EU • Harmonization of study programmes of the Bologna Process • Full implementation of ECTS • Participation -

Gypsy Refugees from Toxic UNMIK Camp Face Deportation from Germany Activists Fear They Will Be Sent Back to the Camp and Believe They Will Die, Should That Happen

Edition 8 • July 28 2008 1.00 • WEEKLY NEWSPAPER NEWS Gypsy refugees from toxic UNMIK camp face deportation from Germany Activists fear they will be sent back to the camp and believe they will die, should that happen THE KOSOV @ POST has learned that one of the Gypsy families that was rescued from LEGAL EAGLES a toxic UNMIK camp in north Mitrovica PG 4 by the German newspaper Bild Zeitung in 2005 is facing a deportation hearing in Hamburg. OPINION Bild Zeitung paid for birth certificates, passports, plane fares and medical treatment - including 3,000 euros per child body scans for the eight member family - after running a feature length report on the tragedy that continues in the camp where 77 have died from lead poisoning. Residents of the camp - most of whom have been living on top of tailings piles from a nearby lead and zinc mine for nine years – have registered extremely KARADZIC BUST: dangerous levels of lead in their blood. GOOD FOR SERBIA One child registered the highest levels of lead poisoning ever recorded. Could the Mustafa family – shown here with Dr. Klaus Runow and PG 6 Dr. Rohko Kim, a Harvard trained medical Paul Polansky and Dija Gidzic of Society for Threatened Peoples – be doctor, has been advising the UN on the returned to the toxic UNMIK camp in north Mitrovica that almost killed lead poisoning in their camps in Kosovo. them once? In a speech delivered in 2005 to WHO, EYEWITNESS UNMIK and the Kosovo Ministry of Health, Dr. Kim said: “The present situation in the Roma community who are now living in the camps is extremely, extremely serious. -

1 LIGJVËNËSIT SHQIPTARË NË VITE Viti 1920 Këshilli Kombëtar I

LIGJVËNËSIT SHQIPTARË NË VITE Viti 1920 Këshilli Kombëtar i Lushnjës (Senati) Një dhomë, 37 deputetë 27 mars 1920–20 dhjetor 1920 Zgjedhjet u mbajtën më 31 janar 1920. Xhemal NAIPI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1920) Dhimitër KACIMBRA Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1920) Lista emërore e senatorëve 1. Abdurrahman Mati 22. Myqerem HAMZARAJ 2. Adem GJINISHI 23. Mytesim KËLLIÇI 3. Adem PEQINI 24. Neki RULI 4. Ahmet RESULI 25. Osman LITA 5. Bajram bej CURRI 26. Qani DISHNICA 6. Bektash CAKRANI 27. Qazim DURMISHI 7. Beqir bej RUSI 28. Qazim KOCULI 8. Dine bej DIBRA 29. Ramiz DACI 9. Dine DEMA 30. Rexhep MITROVICA 10. Dino bej MASHLARA 31. Sabri bej HAFIZ 11. Dhimitër KACIMBRA 32. Sadullah bej TEPELENA 12. Fazlli FRASHËRI 33. Sejfi VLLAMASI 13. Gjergj KOLECI 34. Spiro Jorgo KOLEKA 14. Halim bej ÇELA 35. Spiro PAPA 15. Hilë MOSI 36. Shefqet VËRLACI 16. Hysein VRIONI 37. Thanas ÇIKOZI 17. Irfan bej OHRI 38. Veli bej KRUJA 18. Kiço KOÇI 39. Visarion XHUVANI 19. Kolë THAÇI 40. Xhemal NAIPI 20. Kostaq (Koço) KOTA 41. Xhemal SHKODRA 21. Llambi GOXHAMANI 42. Ymer bej SHIJAKU Viti 1921 Këshilli Kombëtar/Parlamenti Një dhomë, 78 deputetë 21 prill 1921–30 shtator 1923 Zgjedhjet u mbajtën më 5 prill 1921. Pandeli EVANGJELI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1921) Eshref FRASHËRI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1922–1923) 1 Lista emërore e deputetëve të Këshillit Kombëtar (Lista pasqyron edhe ndryshimet e bëra gjatë legjislaturës.) 1. Abdyl SULA 49. Mehdi FRASHËRI 2. Agathokli GJITONI 50. Mehmet PENGILI 3. Ahmet HASTOPALLI 51. Mehmet PILKU 4. Ahmet RESULI 52. Mithat FRASHËRI 5. -

Albania Constitution Watch Summer 2002, EECR.Pdf

East European Constitutional Review Volume 11 Number 3 Summer 2002 Constitution Watch 2 A country-by-country update on constitutional politics in Eastern Europe and the ex-USSR Special Reports 62 Martin Krygier presents ten parables on postcommunism 66 Vladimir Pastukhov offers a fresh take on law’s failure in Russia 75 Tatiana Vaksberg reports from The Hague Tribunal Focus Election Roundup 80 Hungary’s Social-Democratic Turn Andras Bozoki 87 European Union Wins Czech Elections—Barely Jiri Pehe 91 Ukraine’s 2002 Elections: Less Fraud, More Virtuality Andrew Wilson Focus The Politics of Land in Russia 99 Russia’s Federal Assembly and the Land Code Thomas F.Remington 105 Power and Property in Russia: The Adoption of the Land Code Andrei Medushevsky Constitutional Review 119 The Challenge of Revolution, by Vladimir Mau and Irina Starodubrovskaya Daniel Treisman Editor-in-Chief Stephen Holmes Contributing Editors Executive Editor Editorial Board Venelin Ganev Alison Rose Shlomo Avineri Robert M. Hayden Alexander Blankenagel Richard Rose Associate Editor Arie Bloed Andras Sajo Karen Johnson Norman Dorsen Cass R. Sunstein Manuscripts Editor Jon Elster Alarik W.Skarstrom Janos Kis Andrei Kortunov Lawrence Lessig Elizabeta Matynia Marie Mendras Peter Solomon East European Constitutional Review,Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer 2002. ISSN 1075-8402 Published quarterly by New York University School of Law and Central European University, Budapest For subscriptions write to Alison Rose, EECR, NYU School of Law, 161 Sixth Ave., 12th floor, New York,NY,10013