Vanuatu National Leasing Profile:A Preliminary Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE COW in the ELEVATOR an Anthropology of Wonder the COW in the ELEVATOR Tulasi Srinivas

TULASI SRINIVAS THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF WONDER THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR tulasi srinivas THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR An Anthropology of Won der Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer ic a on acid-f ree paper ∞ Text designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Cover designed by Julienne Alexander Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Srinivas, Tulasi, author. Title: The cow in the elevator : an anthropology of won der / Tulasi Srinivas. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2017049281 (print) | lccn 2017055278 (ebook) isbn 9780822371922 (ebook) isbn 9780822370642 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822370796 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Ritual. | Religious life—H induism. | Hinduism and culture— India— Bangalore. | Bangalore (India)— Religious life and customs. | Globalization—R eligious aspects. Classification: lcc bl1226.2 (ebook) | lcc bl1226.2 .s698 2018 (print) | ddc 294.5/4— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2017049281 Cover art: The Hindu goddess Durga during rush hour traffic. Bangalore, India, 2013. FotoFlirt / Alamy. For my wonderful mother, Rukmini Srinivas contents A Note on Translation · xi Acknowl edgments · xiii O Wonderful! · xix introduction. WONDER, CREATIVITY, AND ETHICAL LIFE IN BANGALORE · 1 Cranes in the Sky · 1 Wondering about Won der · 6 Modern Fractures · 9 Of Bangalore’s Boomtown Bourgeoisie · 13 My Guides into Won der · 16 Going Forward · 31 one. ADVENTURES IN MODERN DWELLING · 34 The Cow in the Elevator · 34 Grounded Won der · 37 And Ungrounded Won der · 39 Back to Earth · 41 Memorialized Cartography · 43 “Dead- Endu” Ganesha · 45 Earthen Prayers and Black Money · 48 Moving Marble · 51 Building Won der · 56 interlude. -

Country Profile – South Africa

Country profile – South Africa Version 2016 Recommended citation: FAO. 2016. AQUASTAT Country Profile – South Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

Appendix 3: Finding Aid for Vanuatu Material in Scotland

ReviewReview ofof PacificPacific Collections in Scottish Museums Appendix 3: Finding Aid for Vanuatu Material in Scotland Produced as part of Pacific Collections in Scottish Museums: Unlocking their knowledge and potential project 2013-2014. For full information and resources visit www.nms.ac.uk/pacific Artefacts and Archives relating to Vanuatu in public repositories in Scotland (United Kingdom) This finding aid has been compiled as a result of a preliminary survey of Pacific Collections in Scottish Museums undertaken between April 2013 and December 2014. The review scoped the extent of Pacific collections in Scotland and identified key strengths and resources for future research. It also compiled Collections Level Descriptions for each regional island group and to highlight significance. The review was undertaken as a partnership across four museums in Scotland with significant or extensive collections from the Pacific region. These partners were National Museums Scotland (Edinburgh); Glasgow Museums; Perth Museum and Art Gallery and Aberdeen University Museums. Each of these museums hold collections from Vanuatu that have clear associations with islands or regions in Vanuatu and relate to well known Scottish missionaries. How to use this finding aid This finding aid provides an overview of Ni-Vanuatu artefact collections in Scotland and where possible related archives or photographs. The following list provides the names of key individuals through which the collections were acquired. The finding aid enables an initial overview of collections and resources and provides contact details for each of the major museums and libraries so that requests for further information can be made. The finding aid should also be used in conjunction with Excel spreadsheets and photographs of artefacts also deposited with the National Archives of Vanuatu. -

PMB Photo 60 [PDF, 259

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Room 4201, Coombs Building College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia Telephone: (612) 6125 0887 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/pambu ITEM LIST PMB Photo 60 PATON, Frank (1906-2002) and Rita (1904-1982)., Slides and photographs of missionary service on the island of Tangoa, New Hebrides (1931-33) and a trip for the 75th Anniversary Celebrations of the Tangoa Training Institute, (Aug 1970), 1931-1970. Image No. PMB Catalogue Title Description Date N.B.: Black & white photos up to 60_100 have original captions, set off between “ ”; the remaining photos are uncaptioned and the descriptions, set off by [ ], may well need correcting. PMBPhoto60_1 Photograph of men and coconuts Photograph of men and coconuts nd Gift envelopes with photographs made by Frank Paton PMBPhoto60_2 [A small hand lettered card] “With best thoughts for the coming year JANUARY1932 Jan 1932 / From: Mr. and Mrs. Frank J. C. Paton, Tangoa. New Hebrides.” [A small photograph] “The Islands of Elia and Araki: (Tangoa in foreground). Beyond these two islands is open sea without land of any kind for a thousand miles – THEN – Small hand lettered card, front AUSTRALIA!” PMBPhoto60_2a Small hand lettered card, back PMBPhoto60_3 [A small hand lettered card] “just a New Year Remembrance. JANUARY, 1932. Jan 1932 FROM: Mr. and Mrs. Frank J. C. Paton, Tangoa. New Hebrides” [A small photograph, identical to that of 60_336] “The Malinoa” (the Inter-Island Steamer) at anchor Small hand lettered card, front between Tangoa and Santo (in the distance)” 1 PATON, Frank (1906-2002) and Rita (1904-1982)., Slides and photographs of missionary service on the island of Tangoa, New Hebrides (1931-33) and a trip for the 75th Anniversary Celebrations of the Tangoa Training Institute, (Aug 1970), 1931-1970. -

The Gambia April 2019

Poverty & Equity Brief Sub-Saharan Africa The Gambia April 2019 In the Gambia, 10.1 percent of the population lived below the international poverty line in 2015 (poverty measured at 2011 PPP US$1.9 a day). In the Greater Banjul Area, which includes the local government areas of Banjul and Kanifing, the country's hub of key economic activities, the poverty rate was lower than in other urban areas. Poverty rates were highest in rural areas, where the poor typically work in the low-productivity agricultural sector, while in urban areas they work in the low-productivity informal service sectors. Even though poverty rates are high in the interior of the country compared to the coastal urban areas, the highest concentration of the poor population is found in direct proximity to the Greater Banjul Area, in the local government area of Brikama. Rapid urbanization in the past triggered by high rural-to-urban migration, led to a massing of poor people, many in their youth, in and around congested urban areas where inequality is high, traditional support systems are typically weak, and women face barriers in labor market participation. High levels of poverty are closely intertwined with low levels of productivity and limited resilience, as well as with economic and social exclusion. The poor are more likely to live in larger family units that are more likely to be polygamous and have more dependent children, have high adult and youth illiteracy rates, and are significantly more exposed to weather shocks than others. Chronic malnutrition (stunting) affects 25 percent of children under the age of five, and non-monetary indicators of poverty linked to infrastructure, health and nutrition illustrate that the country is lagging vis-à-vis peers in Sub-Saharan Africa. -

The Geography and History of *R-Loss in Southern Oceanic Languages Alexandre François

Where *R they all? The Geography and History of *R-loss in Southern Oceanic Languages Alexandre François To cite this version: Alexandre François. Where *R they all? The Geography and History of *R-loss in Southern Oceanic Languages. Oceanic Linguistics, University of Hawai’i Press, 2011, 50 (1), pp.140 - 197. 10.1353/ol.2011.0009. hal-01137686 HAL Id: hal-01137686 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01137686 Submitted on 17 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Where *R they all? The Geography and History of *R-loss in Southern Oceanic Languages Alexandre François LANGUES ET CIVILISATIONS À TRADITION ORALE (CNRS), PARIS, AND AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Some twenty years ago, Paul Geraghty offered a large-scale survey of the retention and loss of Proto-Oceanic *R across Eastern Oceanic languages, and concluded that *R was “lost in proportion to distance from Western Oceanic.” This paper aims at testing Geraghty’s hypothesis based on a larger body of data now available, with a primary focus on a tightly knit set of languages spoken in Vanuatu. By observing the dialectology of individual lexical items in this region, I show that the boundaries between languages retaining vs. -

Fifth National Report

FIFTH NATIONAL REPORT Executive Summary Vanuatu is an array of 83 volcanic islands that were formed during the Miocene Era. Her geographical location means that Vanuatu’s biological diversity has developed commonalities with Pacific Island Countries in close proximity such as that of Fiji and Solomon Islands. Vanuatu is fundamentally an agricultural society, where the majority of the population is involved in farm and fishing activities, either for subsistence, livelihood or cash income. The Overarching Productive Sector Policy 2012-2017 also identifies agriculture, forestry and fisheries as priority areas for economic development. In 2013, the Vanuatu National Statistics Office estimated the population of Vanuatu to be 264,000 people, with 75% of the population living in the rural areas. A large portion of the population still depends heavily on the Vanuatu productive sector therefore, the Government has a crucial role to play in defining a policy and institutional framework which both enables and encourages good participation and high performance from all sector stakeholders. The country’s development goals and priorities in the Priorities and Action Agenda (PAA) 2006-2015 identify the productive sector as an engine for investment, economic growth and employment. The sector’s contribution to the overall economic growth has required a strategic commitment by the Government. This is so the Government can support and facilitate an enabling environment for private sector operators. The need to protect and conserve the resources that are critical elements of the productive sector saw Vanuatu commit itself internationally to the Convention on Biological Diversity in the 1992. Since its ratification of this Convention, Vanuatu has made significant progress in ensuring it meets all of its obligations. -

The Coconut Crab the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) Was Established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament

The Coconut Crab The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has a special research competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR Monograph Series This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR's research objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on developing countries. Reprinted 1992 © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research G.P.O. Box 1571, Canberra, ACT, Australia 2601 Brown, I.W. and Fielder, D .R. 1991. The Coconut Crab: aspects of the biology and ecology of Birgus Zatro in the Republic of Vanuatu. ACIAR Monograph No.8, 136 p. ISBN I 86320 054 I Technical editing: Apword Partners, Canberra Production management: Peter Lynch Design and production: BPD Graphic Associates, Canberra, ACT Printed by: Goanna Print, Fyshwick The Coconut Crab: aspects of the biology and ecology of Birgus latro in the Republic of Vanuatu Editors I.w. Brown and D.R. Fielder Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia 199 1 The Authors I.W. Brown. Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Southern Fisheries Centre, PO Box 76, Deception Bay, Queensland, Australia D.R. Fielder. Department of Zoology, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia W.J. Fletcher. Western Australian Marine Research Laboratories, PO Box 20, North Beach, Western Australia, Australia S. -

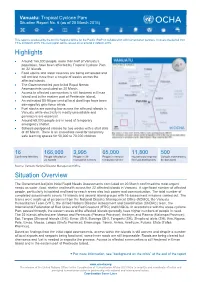

OCHA VUT Tcpam Sitrep6 20

Vanuatu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 6 (as of 20 March 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 19 to 20 March 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 21 March 2015. Highlights Around 166,000 people, more than half of Vanuatu’s population, have been affected by Tropical Cyclone Pam on 22 islands. Food stocks and water reserves are being exhausted and will not last more than a couple of weeks across the affected islands. The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March. Access to affected communities is still hindered in Emae Island and in the eastern part of Pentecote Island. An estimated 50-90 per cent of local dwellings have been damaged by gale-force winds. Fuel stocks are running low across the affected islands in Vanuatu while electricity is mostly unavailable and generators are essential. Around 65,000 people are in need of temporary emergency shelter. Schools postponed classes for two weeks with a start date of 30 March. There is an immediate need for temporary safe learning spaces for 50,000 to 70,000 children. 16 166,000 3,995 65,000 11,800 500 Confirmed fatalities People affected on People in 39 People in need of Households targeted Schools estimated to 22 islands evacuation centres temporary shelter for food distributions be damaged Source: Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office Situation Overview The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March confirmed the most urgent needs as water, food, shelter and health across the 22 affected islands in Vanuatu. -

VANUATU \ A.A A

MAY 1999 : :w- 22257 _~~~ / Public Disclosure Authorized _. PACIFIC ISLANDS : -s,STAKEHOLDER Public Disclosure Authorized PARTICIPATION ] . ~~~-4 £\ / IN DEVELOPMENT: VANUATU \ A.A a - N ~~~DarrylTyron Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PACIFIC ISLANDs DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES _ MBEASTASIA AND PACIFIC REGION PAPUA NEW GUINEAAND PACIFIC ISLANDS COUNTRYMANAGEMENT UNIT DISCUSSION PAPERS PRESENT RESULTS OF COUNTRYANALYSES UNDERTAKENBY THE DEPARTMENTAS PART OF ITS NORMAL WORK PROGRAM. To PRESENTTHESE RESULTS WITH THE LEAST POSSIBLE DELAY, THE TYPESCRIPTOF THIS PAPER HAS NOT BEEN PREPARED IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PROCEDURES APPROPRIATE FOR FORMAL PRINTED TEXTS, AND THE WORLD BANK ACCEPTS NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ERRORS. SOME SOURCES CITED IN THIS PAPER MAY BE INFORMAL DOCUMENTS THAT ARE NOT READILYAVAILABLE. THE WORLD BANK DOES NOT GUARANTEETHE ACCURACY OF THE DATA INCLUDED IN THIS PUBLICATION AND ACCEPTS NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY CONSEQUENCESOF ITS USE. PACIFIC ISLANDS STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION IN DEVELOPMENT: VANUATU MAY, 1999 A Report for the World Bank Prepared by: Darryl Tyron Funded by the Government of Australia under the AusAID/World Bank Pacific Facility The views, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this study are the result of research supported by the World Bank, but they are entirely those of the author and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organisations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. For further copies of the report, please contact: Mr. David Colbert Papua New Guinea and Pacific Islands Country Management Unit East Asia and Pacific Region The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC, U.S.A. -

バヌアツ バヌアツ Vanuatu Vanuatu

Vanuatu Vanuatu Vanuatu Vanuatu Vanuatu Vanuatu Vanuatu Vanuatu バヌアツ バヌアツ Vanuatu Vanuatu 国際機関 太平洋諸島センター 〒101-0052 東京都千代田区神田小川町3-22-14 明治大学 紫紺館1階 Tel:03-5259-8419/Fax:03-5259-8429 http://www.pic.or.jp E-mail:[email protected] 国際機関 太平洋諸島センター CW6_A7034A01.indd 1 2013/07/22 9:35:33 刊行にあたって 本書は太平洋諸島センターの活動対象となっている太平洋諸 国13カ国・1地域のうち、バヌアツ共和国に関する観光情報 をできるだけ詳しくまとめたものです。また、同国をできるだ け深く理解して頂くために、観光情報以外にも同国の歴史、経 済、社会等についても紹介しています。 バヌアツ共和国は、何年か前に「世界で一番幸せな国」とし て報じられましたが、島ごとに異なるその多種多様な文化が英 国とフランス文化と共存し、互いに影響しあって、「和」を大 切にする独特の文化を育んでいます。また、同国にあるペンテ コスト島の「ランド・ダイビング」は「バンジー・ジャンプ」 の基になったことで良く知られています。 バヌアツを訪れる観光客のほとんどはオーストラリア、 ニュージーランドからで、日本からの観光客数は2013年3月 現在600人ほどですが、バカンスや新婚旅行の行き先として 少しずつ口コミで人気が高まってきています。 本書が日本におけるバヌアツについての関心と理解を深め、こ れから同国を訪問されようとする方々の参考となれば幸いです。 バヌアツ共和国 2013年8月1日 発行日:2009年2月1日 初版発行 国際機関 太平洋諸島センター 2013年8月1日 第二版発行 発 行:国際機関 太平洋諸島センター(PIC) 〒101-0052 東京都千代田区神田小川町3-22-14 明治大学紫紺館1F 電話:03-5259-8419 FAX:03-5259-8429 E-mail:[email protected] URL:http://www.pic.or.jp 航空路線や現地事情は刻々と変化します。 国際機関「太平洋諸島センター(PIC)」は、新しい情報を得次第、ホームページ (http://www.pic.or.jp)でも情報を公開していますので併せご参照下さい。 Printed in Japan またご出発前には各ホームページ等で最新情報をチェックされることをお勧めします。 無断での複写・複製はお断りします。 CW6_A7034A02.indd 2 2013/08/02 19:55:10 バヌアツ 正式国名 バヌアツ共和国(Republic of Vanuatu) 面積 12,190平方キロメートル(新潟県とほぼ同じ大きさ) 人口 243,304 人(2009年国勢調査) 首都 ポートビラ(Port Villa) 民族 メラネシア系94%、英仏系(4%)、中国系、ベトナム系など 主要言語 ビスラマ語(ピジン英語)、英語、仏語 宗教 人口の 約98%がキリスト教 政体 共和制 1人当りGNI 2,870米ドル(2011年、世界銀行) 通貨 バツ(Vatu=VT) 電話の国番号 (678)+(相手先の番号) バヌアツ 0 500 1,000km パラオ ミクロネシア連邦 インドネシア ナウル パプアニューギニア ツバル ソロモン諸島 ウォリス・フツナ フィジー オーストラリア トンガ ニューカレドニア ニュージーランド 目 次 バヌアツ共和国の概要……………………………………………2 -

Gazetteer of New Hebrides Place Names/Nomenclature Des Noms Geographiques Des Nouvelles-Hebrides

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Se�ie� V - No. 15 GAZETTEER OF NEW HEBRIDES PLACE NAMES � NOMENCLATURE DES NOMS GEOGRAPHIQUES DES � NOUVELLES-HEBRIDES D.T. Tryon & R. Gely, eds Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Tryon, D.T. and Gly, R. Gazetteer of New Hebrides place names/Nomenclature des noms geographiques des Nouvelles-Hebrides. D-15, xxxvi + 188 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1979. DOI:10.15144/PL-D15.cover ©1979 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the L�ngu����e C��ele 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCASIONAL PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS EDITOR: S.A. Wurm. ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton. EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. Bender, university of Hawaii J. Lynch, University of Papua D. Bradley, University of Melbourne New Guinea A. Capell, university of Sydney K.A. McElhanon, University of Texas S. Elbert, University of Hawaii H. McKaughan, University of Hawaii K. Franklin, Summer Institute of P. MUhlhausler, Technische Linguistics Universitat Berlin W.W. Glover, Summer Institute of G.N. O'Grady, University of Linguistics Victoria, B.C. G. Grace, University of Hawaii A.K. Pawley, University of Hawaii M.A.K. Halliday, University of K. Pike, University of Michigan; Sydney Summer Institute of Linguistics A. Healey, Summer Institute of E.C. Polom�, University of Texas Linguistics G. Sankoff, Universite de Montreal L.