No.32 March 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15.8.2014 15,894 Brand Name (In Chinese) 品牌名稱(中文) Product

Generation Date: 15.8.2014 List of Small Volume Exemption Products 已獲小量豁免產品名單 Total Number of SVE products: 15,894 (已獲小量豁免產品總數): Brand Name (in Product Name (in Chinese) Brand Name (in English) Product Name (in English) Exemption End Date Effective Date for Exemption No. Chinese) 產品名稱 (中文) 品牌名稱 (英文) 產品名稱 (英文) (豁免終止日期) Revocation of (豁免編號) 品牌名稱 (中文) Exemption (豁免撤銷生效日期) Nil Nil Nil Sanko Rice Roll with Seaweed 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007124 Nil Nil Nil Sanko Rice Cracker - Castard 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007123 Nil Nil Nil Wonderland Panda - Choco Ball 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007083 Nil Nil Nil Wonderland Candy - Animal Assort 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007082 Nil Nil Nil Asahi Ice Limone 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007081 Nil Nil Nil Asahi Ice Grapefruit 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007079 Nil Nil Nil MARUESU SNACK - WASABI SOY SAUCE TASTE 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007078 Nil Nil Nil MARUESU SNACK - HOKKAIDO CHEESE TASTE 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007072 Nil Nil Nil KASUGAI BEACH SODA CANDY 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007071 Nil Nil Nil Nissin Corn Flakes 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007070 Nil Nil Nil MARUESU SNACK - MAYONNAISE TASTE 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007069 Nil Nil Nil KASUGAI UME AME 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007068 Nil Nil Nil Bonchi Wheat Snack - Seaweed 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007067 Nil Nil Nil Bonchi Wheat Snack - Spicy 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007066 Nil Nil Nil Kasugai Gummy Candy - Muscat Flavor 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007065 Nil Nil Nil Kasugai Gummy Candy - Grape Flavor 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007064 Nil Nil Nil Kasugai Gummy Candy - Peach Flavor 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007063 Nil Nil Nil Bonchi Rice Snack 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007062 Nil Nil Nil Nissin -

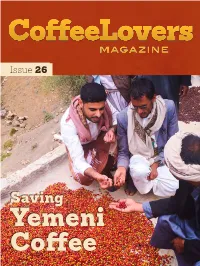

The Journey of One Man Trying to Save Yemeni Coffee (2015)

Issue 26 Saving Yemeni Coffee Coffee at its Origin The journey of one man trying to save Yemeni Coffee Ummah Wide Interviews Mokhtar Alkhanshali of Mocha Mill ummah wide: We are with Mokhtar mokhtar alkhanshali: I was recently talking Alkhanshali, the President and Founder of Mocha to one of my childhood mentors, Nasseam Mill — Yemeni Speciality Coffee, a company with a Elkarra, and he was reminding me that when I powerful social mission that is bridging the worlds was in High School I was always talking about of coffees roots in Yemen with the speciality coffee coffee in Yemen and the history of coffee in industry in the United States. One of the incredible Yemen. In particular he said I was talking things about this project is that you stand at the about the issue of Qat, the locally consumed intersection of two amazing histories, on one side stimulant in Yemen and how it’s taken the place you come from a family who has been growing of coffee in agriculture and someone needs to coffee for hundreds of years in Yemen, the first do something about it. Stephen Ezill, one of place to cultivate and commercialize coffee in the my friends at Boot Coffee said that his brother world. On the other side you are the first Arab/ called me a hero of a thousand faces because Yemeni certified speciality coffee Q grader. What there are so many different ways of looking can you tell us about these two worlds and how at what I am doing and different routes that you came to this moment in your life founding guided me to this point here. -

Roaster Guild Certification Program Handbook

Coffee Taster CERTIFICATE PROGRAM (CT) Ver. 1.0/January 2013 Specialty Coffee Association of America Cupper Guild of America 330 Golden Shore, Suite 50, Long Beach, California 90802 TEL: 562-624-4193 FAX: 562-624-4101 Introduction to the Coffee Taster (CT) Certificate Program Guide Welcome to the CT Certificate Program of Specialty Coffee Association of America. This guide is to provide general information to candidates of the program. It contains background information, definitions, descriptions, and procedures for the program. TABLE OF CONTENTS CT INFORMATION: Background ................................................................................................................... 1 CT CERTIFICATE PROGRAM: Overview, Purpose, Eligibility and Requirements .................................... 2 CT CERTIFICATE PROGRAM: Curriculum Summary .................................................................................. 3 MODULE 1 : Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 4 MODULE 1 : Classes, Rationale and Expectations ...................................................................................... 5 MODULE 2 : Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 6 MODULE 2 : Classes, Rationale and Expectations ...................................................................................... 7 MODULE 3 : Overview .................................................................................................................................... -

Envision Odessa Master Plan

2016 S XA , TE O DESSA Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ v Odessa’s Roadmap .............................................................................................. 3 Community Snapshot: Who We Are ................................................................... 9 Our History .............................................................................................................................................. 10 Population ............................................................................................................................................... 12 Demographics .......................................................................................................................................... 15 Demographic Changes ............................................................................................................................. 18 Economics ................................................................................................................................................ 20 Planning Area .......................................................................................................................................... 26 Existing Land Use .................................................................................................................................... -

KCGI: the Kyoto College of Graduate Studies for Informatics

Japan’s first IT professional graduate school KCGI:KCGI: TheThe KyotoKyoto CollegeCollege ofof GraduateGraduate StudiesStudies forfor InformaticsInformatics Study cutting-edge IT in Kyoto, Japan Link to the Pioneer Spirit URL: https://www.kcg.edu/ E-mail: [email protected] Inquiries: Admissions Section, The Kyoto College of Graduate Studies for Informatics 7 Tanakamonzen-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8225, Japan Telephone: 075-681-6334 (+81-75-681-6334 outside Japan) Fax: 075-671-1382 (+81-75-671-1382 outside Japan) 英 語 202107 No. 1 & the Only One ! In order to cultivate high level professionals in the field of IT School Philosophy The objective of our school is to train highly-qualified information With the advancements in science and technology, technology professionals with strong practical knowledge remarkable technological innovations, and radical of the current business practices, a solid theoretical background, and a creative and innovative spirit which will enable them to meet socioeconomic changes (diversi�ication, increasing the demands of society and to be responsible for the current complexity, increasing sophistication, globalization, and future generation. and the arrival of the age of IoT, etc.) in recent years, expectations for the education of high level IT professionals viable both in Japan and internationally KCGI's Mission and Purpose are rapidly increasing. In the �ield of IT, however, which spans such To meet the need for high level and diverse human resources specialty �ields as information and management, in our IT society and, furthermore, to contribute to the realization the number of colleges and graduate schools able to of a high level information society and the development of meet the challenges of cultivating high level IT the economy through the provision of high level IT professionals system professionals has been virtually almost zero who possess extensive knowledge and high level skills beyond what is conventional and who are also internationally minded until now. -

Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF CHEMICAL AND BIO-ENGINEERING FOOD ENGINEERING PROGRAMME Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia A Thesis Submitted to the School of Chemical & Bio-Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) By Muluken Zenebe Bolka November 7, 2019 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia By Muluken Zenebe Bolka A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) School of Chemical and Bio-Engineering Addis Ababa Institute of Technology Addis Ababa University Advisor: Dr. Eng. Shimelis Admassu (Associate Professor) Title Page Copyright © Muluken Z. Bolka, 2019 i Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that this thesis presented for the attainment of the degree of Master of Science in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) has been composed solely by myself and has not been presented or submitted, in part or as a whole, for a degree in any other institution or university. The thesis presented is my original work and all sources of information or materials used for the thesis have been duly acknowledged. Mr. Muluken Zenebe Bolka Signature: _______________ Date: ___________________ M.Sc. Candidate This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval and done under my supervision as University advisor. Dr. Eng. Shimelis Admassu Emire Signature: ______________ Date: ____________________ Advisor The undersigned members of the thesis examining board appointed to examine the thesis of Mr. -

Coffee Flavor and Flavor Attributes That Drive Consumer Liking for These Novel Products

beverages Review Coffee Flavor: A Review Denis Richard Seninde and Edgar Chambers IV * Center for Sensory Analysis and Consumer Behavior, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66502, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 June 2020; Accepted: 3 July 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: Flavor continues to be a driving force for coffee’s continued growth in the beverage market today. Studies have identified the sensory aspects and volatile and non-volatile compounds that characterize the flavor of different coffees. This review discusses aspects that influence coffee drinking and aspects such as environment, processing, and preparation that influence flavor. This summary of research studies employed sensory analysis (either descriptive and discrimination testing and or consumer testing) and chemical analysis to determine the impact aspects on coffee flavor. Keywords: coffee flavor; processing; preparation; emotion; environment; consumer acceptance 1. Introduction The coffee market is currently worth USD 15.1 billion and growing. This market is mainly comprised of roasted, instant, and ready-to-drink (RTD) coffee [1]. The flavor of a roasted coffee brew is influenced by factors such as the geographical location of origin, variety, climatic factors, processing methods, roasting process, and preparation methods [2–10]. The differences in sensory properties can, in turn, affect consumers’ preferences for and emotions or attitudes toward coffee drinking [11]. 1.1. Motivations for Drinking Coffee As indicated by Phan [12], the motivations for drinking coffee can be grouped under 17 constructs: liking, habits, need and hunger, health, convenience, pleasure, traditional eating, natural concerns, sociability, price, visual appeal, weight control, affect regulation, social norms, social image [13], choice and variety seeking [12,14,15]. -

Extract Series TEMPLATE: COFFEE & MILK

Extract Series TEMPLATE: COFFEE & MILK THaveaste andyou evercompa tastedre 3 d2i fmilksferent side sugars by sideat 3 anddiffe wonderedrent levels howof refinement, they could t henbe seeso different? how each sugar impacts the flavor of two or more coffees with different flavor profiles. Or had the same coffee at 2 different shops that use different milks and Materials:wondered whyRefined the cappuccinossugar, Turbinado highlighted sugar, Sucanat/Deme totally differentrera/Muscavado flavors? sugar, small tasting cups or spoons for sugars, small tasting cups for coffees, scales,In this exercise,grinders, you’llbrewing compare and service the taste for coof fmilksfees. from 3 different dairies. Prepare like a coffee cupping and have attendees taste with cupping spoons. PEachrovide of thea brief 3 milks introduc shouldtion be of prepared the exercise, cold briefly and steamed. describing Optional: the following: Also prepare each of the 3 milks as a cappuccino with the same coffee/recipe for each. • Why are we doing the exercise • What items will be tasted This exercise• What toworks reflect best upon if you as canyou’ includere tasting at least(sensory 1 totally sensa differenttions, intensity milk. vs. Non-homogonized,flavor) UHT Pasteurization, All Jersey Cows, or something attendees• Best might prac tnotices have for exe accessrcise to (tas att ingtheir o rcafé.der, tasting multiple times, tasting at different dosages) Materials: 3 different milks from 3 different dairies, cupping spoons, glasses Pforrocedu all milkres: samples, buckets for dumping, rinse water, towels, espresso machine equipment for steaming the milk and/or preparing coffee. 1. Taste the sugars. Provide a brief introduction of the exercise, briefly describing the following:• Refined Sugar - Full refinement, only sucrose is left. -

How Business Strategy Is Transforming Rwanda

How Business Strategy is Transforming Rwanda NEAL DONAHUE "Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. 'It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out. -VACLAV HAVEL In July 1994, forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) entered Kigali and ended a genocide that took the lives of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus. The military actions of the RPF, the creation of the government of national unity, and the assistance of international donors restored hope to Rwanda. Millions of displaced people returned to Rwanda and began the effort to rebuild their lives. Over the past decade, Rwanda has used this hope to build a new society and create the foundation of a stable economy. Rwanda's economy grew steadily during the last decade, and the standard of living is slowly improving. The Government of Rwanda has set the target of achieving middle income status by 2020. To achieve this ambitious goal, Rwanda must have a GDP per capita of US$900/year. Assuming the population continues to grow at recent historic rates, Rwanda will have 16 million citizens in 2020. Taken together, that means that the economy of Rwanda must grow from its US$2 billion in 2000 to almost US$14.5 billion in 2020. What can Rwanda do to sustain a required growth rate of 8 percent per year? A nation's standard of living is determined by its productivity-that is, how well its citizens work together to create value for foreign customers and for one another. -

Charlotte's Coffee House

DUBUQUE365.com CHARLOTTE’S COFFEE HOUSE BY RICH BelMONT With new coffee shops popping up all over Dubuque you might Obviously there is a list of coffee beverages to choose from. them to throw in mushrooms not have noticed Charlotte’s Coffee House at the corner of 11th Of course brewed coffee is always available but the real fun and tomatoes too. At lunch and White Streets. It has been in operation for six months and is in trying the specialties. Here are some you might not be time I prefer the Turkey & already has a devoted following of coffee aficionados. familiar with: Dressing Panini. This one has roasted turkey, Monterey Don Rusk and his wife, Espresso (ehss-press-oh) – a strong, thick, syrupy coffee Jack or Swiss cheese, sage Cheryl, are Dubuque natives made by forcing nearly boiling water under pressure through dressing, cranberry sauce and the owners of Charlotte’s tightly packed finely ground coffee beans. and pesto. It was supposed to Coffee House. Don also owns be a seasonal special for Thanksgiving but so many customers and operates Rusk Metal Cappuccino (cap-poo-chee-no) – prepared with espresso, hot kept asking for it they had to add it to the regular menu. Company in Epworth, IA. milk and steamed milk foam. (Fun Fact: the foam on top acts He has been in the metal as an insulator and helps retain the heat of the espresso By the way do you know how we got to enjoy a Panini? Panini business for over 20 years. allowing it to stay hotter longer.) (pah-nee-nee) is the plural of the Italian word Panino or bread Cheryl recently retired from John Deere Dubuque Works where roll. -

Innovation and LEADERSHIP for 70 YEARS!

TIN RA G 7 EB 0 L Y • E E C A R S A MIT! T • • • • MAY 3, 2019 Inspiring Student RESEARCH innovation and LEADERSHIP FOR 70 YEARS! 70TH ANNUAL MASSACHUSETTS HIGH SCHOOL DIVISION SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR OFFICIAL PROGRAM AND ABSTRACT BOOK 2019 MASSACHUSETTS SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR Official Program & Abstract Book May 2 - 4, 2019 CELEBRATING MSEF’S 70TH ANNIVERSARY! 2019 Massachusetts Science & Engineering Fair Fish is proud to support STEM learning and the Massachusetts Science and Engineering Fair. YOU INSPIRE US TABLE OF CONTENTS 2019 Fair Schedule of Events Welcome MSEF Leadership Greetings Honorable Charlie Baker Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts The Honorable Karen Polito Lt. Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts 2019 Sponsors, Donors & Award Contributors 2019 Massachusetts ISEF Delegation Curious Minds Initiative (CMI) & STEM Teacher Professional Development Courses Career Opportunities Presentations (COP) Honoring MSEF Volunteer Leaders/ Regional Science Fair Network 2019 Science Fair Expo 2019 Salute to Judges 2019 Exhibitors by Student’s Last Name City/Town, School, Last Name Team Projects 2019 Exhibitor Abstracts CATEGORY PAGE Behavioral Science 78 Biochemistry 88 Biology 2 Chemistry 156 Computers 141 Earth & Space Science 101 Engineering 54 Environmental Science 105 Mathematics 126 Physics & Electronics 130 2019 MSEF Board of Directors 2019 MSEF High School Committee 2019 Fair Acknowledgments A proud sponsor of the 2019 Massachusetts State Science and Engineering Fair 50+ majors and minors focused on science, technology, engineering, mathematics, business, and the arts Traditional New England campus located in Worcester, Mass.— the 2nd largest city in New England Project-based curriculum providing career-launching, real-world experience Global Projects Program, offering students an immersive, life-changing experience solving problems with global impact TOP TOP TOP 10 10 50 Most Popular Study Best Colleges for Women Most Innovative Abroad Program in STEM fields Schools Princeton Review Best Colleges Online U.S. -

Foreign Agents Registration Act | Department of Justice

u.s. Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530 Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, for the six months ended June 30, 1996 Report of the Attorney General to the Congress of the United States on the Administration of the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, for the six months ended June 30, 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Text of Report ANGOLA 6 ANGUILLA 9 ANTIGUA & BARBUDA 10 ARGENTINA 11 ARUBA 13 AUSTRALIA 16 AUSTRIA 21 AZERBAIJAN 24 BAHAMAS 26 BAHRAIN 29 BARBADOS 30 BELARUS 32 BELGIUM 33 BENIN 36 BERMUDA 37 BOLIVIA 41 BRAZIL 42 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 44 BRUNEI 46 BULGARIA 47 CAMBODIA 48 CAMEROON 49 CANADA 50 CAPE VERDE 76 CAYMAN ISLANDS 77 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 80 CHILE 81 CHINA 83 TAIWAN 90 COLOMBIA 100 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 106 COSTA RICA 107 CROATIA 109 CURACAO 111 CYPRUS 113 CZECH REPUBLIC 115 DENMARK 116 DOMINICA 118 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 119 ECUADOR 121 EGYPT 122 EL SALVADOR 123 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 126 ETHIOPIA 127 FINLAND 129 FRANCE 131 GABON 142 GEORGIA 144 GERMANY 145 GHANA 157 GREAT BRITAIN 158 GREECE 178 GRENADA 179 GUADELOUPE & MARTINIQUE 181 GUATEMALA 182 GUERNSEY 183 GUINEA 184 GUINEA-BISSAU 185 GUYANA 186 HAITI 187 HONDURAS 191 HONG KONG 192 HUNGARY 199 ICELAND 200 INDIA 201 INDONESIA 205 INTERNATIONAL 210 IRAN 227 IRELAND 228 ISRAEL 232 ITALY 240 JAMAICA 244 JAPAN 249 JORDAN 295 KAZAKHSTAN 296 KOREA, REPUBLIC OF 297 KOSOVA 310 KUWAIT 311 LEBANON 313 LIBERIA 314 LUXEMBOURG 315 MACAU 316 MACEDONIA 317 MALAWI 318 MALAYSIA 319 MALDIVES 321 MALTA 322 MARSHALL ISLANDS 324 MAURITANIA 326