Review Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

James Mase, C.A.S

JAMES MASE, C.A.S. Production Sound Mixer Member IATSE 695 & 479 James Mase has worked in sound his entire adult life in production, post production and music. No surprise, he has a deep understanding of the process and of the technical and engineering side. Starting out in music in Boston, James helped engineer the first New Edition album. He then moved to New York and worked in music engineering for artists like Run-DMC, Chaka Kahn and others. Another move back to Boston introduced James to video production and post work including commercial work and his first experience with sound for picture. Three years were spent on projects taking him to Europe, Russia and South America. James is based in Atlanta, Georgia. Television (Selected Credits); Production Director/Producer/Company/Network 61st STREET (Season 1) Various / Michael B. Jordan, Hilary Salmon / AMC THE WALKING DEAD (Season 11, 3 Episodes) Various / Gale Anne Hurd, David Alpert / AMC DISPATCHES FROM ELSEWHERE (Season 1) Various / Scott Rudin, Eli Bush / AMC Studios / AMC THE PASSAGE (Full Season) Various / Ridley Scott / Scott Free / Fox LODGE 49 (Seasons 1 & 2) Various / Paul Giamatti / Touchy Feely / AMC CHAMPAIGN, ILL (Season 1) Various / Jamie Tarses / Sony TV / YouTube LOVE IS … (Season 1, 6 eps) Salim Akil / Oprah Winfrey / Warner Horzizon / OWN SURVIVOR’S REMORSE (Season 4) Various / LeBron James, Tom Werner / Starz DAYTIME DIVAS (Full season) Various / Josh Berman, Star Jones / Sony TV / VH1 NOTORIOUS (2016 pilot) Michael Engler / Jeff Kratinetz / Sony TV / ABC POWERS -

MUSIC SUPERVISION & MUSIC CONSULTING CREDITS Flash Of

MUSIC SUPERVISION & MUSIC CONSULTING CREDITS Flash of Genius - Universal/Spyglass Ent. Directed by Marc Abraham, produced by Gary Barber and Roger Birnbaum. Composer: Aaron Zigman. The Great Debaters - The Weinstein Co/MGM/Harpo Films Directed by Denzel Washington, produced by Todd Black, Oprah Winfrey, Kate Forte, and Joe Roth. Composer: James Newton Howard. G. MARQ ROSWELL Producer of “on-camera” songs. Soundtrack Album on Atlantic Records. Soundtrack Album Producer. P.O. Box 217 Pacific Palisades The Grand - Insomnia Media California 90272 Directed by Zak Penn, produced by Bobby Schwartz and Jeff Bowler. Composer: Stephen Endelman. Phone 310.454.1280 Cell 310.488.0031 The Bronx Is Burning - ESPN Ent./Tollin Robbins Productions Fax 310.230.0132 Directed by Jeremiah Chechik, produced by Mike Tollin. [email protected] Composer: Tree Adams. www.35sound.com The Brothers Solomon - Sony/Revolution Studios Directed by Bob Odenkirk, produced by Tom Werner, Marcy Carsey, and Matt Berenson. Composer: John Swihart. Soundtrack Album on Lakeshore Records. Soundtrack Album Producer. Directed by John Ford - Turner Classics Directed by Peter Bogdanovich, produced by Frank Marshall. Hard Luck - Sony/Kushner Productions Directed by Mario Van Peebles, produced by Don Kushner, Brad Wyman, and G. Marq Roswell. Composer:Tree Adams. Last Day of Summer - Nickelodeon/MTV Directed by Blair Treu, produced by Jane Startz. Composers: Darby & Kotch. Iraq For Sale: The War Profiteers - Brave New Films Directed by Robert Greenwald, produced by Devin Smith and Sarah Feeley. Composer: Tree Adams. Let’s Go To Prison - Universal/Strike/Carsey-Werner Directed by Bob Odenkirk, produced by Marc Abraham, Tom Werner, Marcy Carsey, and Matt Berenson. -

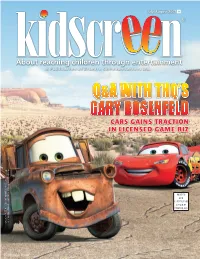

Q&A with Thq's Gary Rosenfeld

US$7.95 in the U.S. CA$8.95 in Canada US$9.95 outside of CanadaJuly/August & the U.S. 2007 1 ® Q&A WITH THQ’S GARY ROSENFELD CCARSARS GGAINSAINS TTRACTIONRACTION IINN LLICENSEDICENSED GGAMEAME BBIZIZ NUMBER 40050265 40050265 NUMBER ANADA USPS Approved Polywrap ANADA AFSM 100 CANADA POST AGREEMENT POST CANADA C IN PRINTED 001editcover_July_Aug07.indd1editcover_July_Aug07.indd 1 77/19/07/19/07 77:00:43:00:43 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 2 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:05:06:05 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 3 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:54:06:54 PMPM #8#+.#$.'019 9 9 Animation © Domo Production Committee. Domo © NHK-TYO 1998. [ZVijg^c\I]ZHiVg<^gah Star Girls and Planet Groove © Dianne Regan Sean Regan. XXXCJHUFOUUW K<C<M@J@FEJ8C<J19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'(2\dX`c1iZfcc`ej7Y`^k\ek%km C@:<EJ@E>GIFDFK@FEJ19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'-2\dX`c1idXippXe\b7Y`^k\ek%km KKS4548.BIGS4548.BIG TTENT.inddENT.indd 2 77/19/07/19/07 66:54:45:54:45 PMPM 1111 F3 to mine MMOG space for TV concepts 114Parthenon4 Kids: Geared up and ready to invest 1177 Will Backseat TV boost Nick’s in-car profile? 225Storm Hawks5 goes jjuly/augustuly/august viral with Guerilla 0077 HHighlightsighlights ffromrom tthishis iissuessue 10 up front 24 marketing France TV to invest in Chrysler and Nick hope more content and global to get more mileage out Special Reports web presence of the minivan set with 29 RADARSCREEN backseat TV feature Fred Seibert’s Frederator Films 13 ppd tries a fresh approach to Parthenon Kids offers 26 digital -

New Producing Courses This Fall

96 Entertainment Studies Enroll at uclaextension.edu or call (800) 825-9971 Reg# 259673CA Through Aug 23: $635 / After: $695 Sneak Preview Westwood: 204 Extension Lindbrook Center Visit entertainment.uclaextension.edu/sneak-preview Wed 7-10pm, Sep 23-Dec 9 ENTERTAINMENT for weekly movie information. ✷✷Sat 2-5pm, Dec 5, 12 mtgs (no mtg 11/11) Sneak Preview: Contemporary Films No refund after Sep 28. and Filmmakers Toni Attell, Emmy-nominated actor, comedian, and STUDIES 804.2 Film & Television 2 CEU mime whose background includes a variety of work Join us for an exclusive preview of new movies before in theater, film, and television. Ms. Attell has opened their public release. Enjoy provocative commentary and for Jay Leno, Steve Martin, and Robin Williams, and 96 Sneak Preview in-depth discussions with invited guests after each has guest-starred on numerous television dramas and sitcoms. 96 Acting screening. Recent films and speakers have included: Wild Tales with director Damian Szifron; McFarland, Reg# 259676CA 98 Cinematography USA with director Niki Caro; Me and Earl and The Through Aug 23: $635 / After: $695 98 Development Dying Girl with actors Thomas Mann, Olivia Cooke and Westwood: 201 Extension Lindbrook Center RJ Cyler; Whiplash with director Damien Chazelle and ✷✷Wed 3:30-6:30pm, Sep 23-Dec 9 99 Directing actor Miles Teller; Birdman with Fox Searchlight Pic- ✷✷Sat 2-5pm, Dec 5, 12 mtgs 100 Post-Production tures’ Claudia Lewis; The Theory of Everything with (no mtg 11/11) actors Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones; The Imita- No refund after Sep 28. 101 Producing tion Game with producers Ido Ostrowsky, Nina Gross- Ernesto González, actor whose credits include co- 102 The Business & Management of Entertainment man and Teddy Schwarzman; Black and White with starring roles in TV shows such as Jimmy Kimmel director Mike Binder and actor/producer Kevin Costner; Live, Professional Friend, Lean Genie, and Discovery’s 103 The Music Business Selma with producers Dede Gardner and Jeremy Top 10 Criminals. -

The Grizzlies Press Kit Feb 17 2019

THE GRIZZLIES Press Kit Running Time: 104 minutes Producers: Stacey Aglok MacDonald, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, Zanne Devine, Damon D’Oliveira and Miranda de Pencier Director: Miranda de Pencier Writers: Graham Yost, Moira Walley-Beckett Cast: Emerald MacDonald, Ben Schnetzer, Paul Nutarariaq, Ricky Marty-Pahtaykan, Booboo Stewart, and Tantoo Cardinal PR CONTACT: Gabrielle Free [email protected] 416-220-0201 THE GRIZZLIES – PRESS KIT Contents: 1. LOGLINE 4 2. SYNOPSIS 4 3. PRODUCTION NOTES – The Making of THE GRIZZLIES 4 a. Overview b. Development History of The Grizzlies c. Miranda de Pencier on Her Origins with THE GRIZZLIES d. Casting e. Collaboration Between North & South f. How The Grizzlies Changed a Town g. Director’s Statement h. About the Town of Kugluktuk i. Music j. Opening Title Sequence 4. CHARACTER BIOS (in order of appearance) 14 a. RUSS (Ben Schnetzer) b. MIKE (Will Sasso) c. ZACH (Paul Nutarariaq) d. ADAM (Ricky Marty-Pahtaykan) e. ROGER (Fred Bailey) f. SPRING (Anna Lambe) g. JANACE (Tantoo Cardinal) h. MIRANDA (Emerald MacDonald) i. KYLE (Booboo Stewart) j. HARRY (Eric Schweig) k. TANNER (Brad Fraser) l. VINNY (Jamie Takkiruq) m. JOHNNY (Seth Burke) n. SAM & LENA (Simon Nattaq & Madeline Ivalu) 5. FILMMAKER BIOS 15 a. MIRANDA DE PENCIER (Director/Producer) b. GRAHAM YOST (Writer) c. MOIRA WALLEY-BECKETT (Writer) d. ALETHEA ARNAQUQ-BARIL (Producer) e. STACEY AGLOK (Producer) 2 f. ZANNE DEVINE (Producer) g. DAMON D’OLIVEIRA (Producer) h. JAKE STEINFELD (Executive Producer) i. FRANK MARSHALL (Executive Producer) 6. ACTOR BIOS 23 a. EMERALD MACDONALD b. BEN SCHNETZER c. PAUL NUTARARIAQ d. RICKY MARTY-PAHTAYKAN e. -

Inside Pictures 10Th Anniversary Yearbook

An inside look at a decade of training from Europe’s leading film business & leadership skills development programme THE NATIONAL FILM AND TELEVISION SCHOOL PRESENTS SUPPORTED BY THE MEDIA PROGRAMME & THE CREATIVE SKILLSET FILM SKILLS FUND Inside Pictures: The Yearbook INSIDE PICTURES INSIDE PICTURES PROVIDES PARTICIPANTS WITH A UNIQUE INSIGHT INTO THE GLOBAL FILM BUSINESS THROUGH ITS ACCESS TO A WIDE RANGE OF INDUSTRY EXPERTS. IT’S AN INVALUABLE APPROACH.” CAMERON MCCRACKEN, PATHÉ UK WHAT MAKES IT DIFFERENT FROM ANYTHING ELSE IS THE LEVEL AT WHICH THE PARTICIPANTS ARE AT, THEY ARE ALREADY IN THE INDUSTRY AND Participants graduate from the 10th Inside Pictures programme in 2013. ALREADY HAVE ACHIEVEMENTS Photograph by Tara Moller. ON THEIR CV.” NIK POWELL, NATIONAL FILM & TELEVISION Inside Pictures is a unique film and other related media, SCHOOL European programme for including cutting-edge digital business training and leadership entrepreneurs and innovators. INSIDE PICTURES HAS DEVELOPED OVER THE LAST development in the film The course is open to DECADE INTO AN ESSENTIAL industry. participants from Europe, with CONSTITUENT OF THE The intensive annual course the programme divided between EUROPEAN MEDIA INDUSTRY.” brings together the full range of London and Los Angeles. CHARLES MOORE, PARTNER, WIGGIN LLP industry disciplines, including Inside Pictures is funded by the INSIDE PICTURES IS A GREAT development, production, sales, European MEDIA programme COURSE THAT GIVES distribution, marketing, finance, and Creative Skillset. For full APPLICANTS A TERRIFIC legal, exhibition and business details of funders and sponsors OVERVIEW OF THE RAPIDLY GROWING INTERNATIONAL FILM affairs. see Page 19. BUSINESS - SOMETHING I WISH Inside Pictures develops the HAD BEEN AVAILABLE TO ME practical knowledge, skills and EARLY IN MY CAREER”. -

STACY KELLY Make-Up Artist IATSE 798

STACY KELLY Make-Up Artist IATSE 798 FILM POWER Department Head Netflix Directors: Henry Joost/Ariel Schulman Cast: Joseph Gordon Levitt, Dominique Fishback, Jamie Foxx FONZO Department Head Bron Studios Director: Josh Trank Cast: Linda Cardellini, Matt Dillon, Kyle MacLachlan, Al Sapienza THE BEGUILED Department Head Focus Features Director: Sofia Coppola Cast: Colin Farrell, Kirsten Dunst, Elle Fanning, Oona Lawrence SURVIVING COMPTON: DRE, SUGE & Department Head MIHEL'LE Director: Janice Cook Sony Cast: Rhyon Nichole Brown, Curtis Hamilton, Donna Biscoe. Jamie Kennedy, Omari Wallace, Vonii Bristow ELVIS AND NIXON Department Head Prescience Director: Liza Johnson Cast: Michael Shannon, Alex Pettyfer, Colin Hanks, Evan Peters, Dylan Penn MIDNIGHT SPECIAL Department Head Warner Bros. Director: Jeff Nichols Cast: Michael Shannon, Joel Edgerton, Kirsten Dunst HOT PURSUIT Department Head New Line Cinema Director: Anne Fletcher Cast: Robert Kazinsky, Matthew Del Negro, Richard T. Jones SELFLESS Assistant Department Head Endgame Entertainment Director: Tarsem Signh Cast: Natalie Martinez, Michelle Dockery, Matthew Goode, Victor Garber, Derek Luke OUR BRAND IS CRISIS Department Head Smokehouse Pictures Director: David Gordon Green Cast: Anthony Mackie, Zoe Kazan, Scoot McNairy, Ann Dowd, Joaquin Almeda THE MILTON AGENCY Stacy Kelly 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Make-Up Artist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 5 THE MAZE RUNNER Department Head 20th Century Fox Director: Wes Ball Cast: Dylan O’Brien, Patricia Clarkson, Will Poulter, Thomas Brody- Sangster RECKLESS Department Head ABC Director: Martin Campbell Cast: Parminda Nagra, Stephen Lang, Patrick Fugit, Eloise Mumford GRUDGE MATCH Assistant Department Head Warner Bros. -

Jon Fauer, ASC Special Report from Russia Russian Cinematographer Style

Jon Fauer, ASC Special Report from Russia Russian Cinematographer Style A lot has happened since Sergei Eisenstein’s classic “Battleship Potemkin” (1925, Mosfilm). The boom years beginning 2000 generated successful blockbusters like “Night Watch” (“Nochnoi Dozor,” 2004, directed by Timur Bekmambetov, cinematography by Sergey Trofimov) and “Mongol” (2007, directed by Sergei Bodrov, cinematography by Sergey Trofimov). “Mongol” was nominated for the 2007 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film as an entry from Kazakhstan. This period of innovation also led to interesting Russian technology being used on major productions worldwide. For example, Filmotechnic (www.filmotechnic.com), founded by Anatoliy Kokush, designed and manufactured lightweight modular camera cranes (Cascade and Traveling Cascade) and gyro-stabilized remote systems (Flight Head, Russian Arm). But, back to Eisenstein. Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein was born in January 1898. His father was an architect, his mother was the daughter of a suc- cessful merchant. He studied architecture and engineering, joined the Red Army in 1918 (his father supported the White Army), and worked on propaganda. In 1920, he moved to Moscow, began working on theatrical productions and writing about film theory and montage. The success of “Potemkin” was followed by “October” (“Ten Days that Shook the World”). In April 1930, he and his entourage (co-director/screenwriter Grigori Aleksandrov and cinematographer Eduard Tisse) Sergei Eisenstein. 1898-1948 arrived in Hollywood. Jesse Lasky and Paramount Pictures gave Poster from “Battleship Potemkin” him a short-term contract for $100,000. James Goodwin writes (in Eisenstein at 100), “They stayed in Hollywood to learn the new sound technology and advanced studio methods. -

Claude Paré Website:Claudepare.Com Production Designer Password: Design Phone

1 Claude Paré Website:claudepare.com Production Designer Password: design Phone. (514) 893-4028 E-mail: [email protected] X-MEN FEATURE 2017 20TH Century Fox Marvel PRODUCTION DESIGNER Director: Simon Kinberg Starring : Jennifer Lawrence, Michael Fassbinder, Sophie Turner, James Mc Avoy. IT FEATURE 2016 Warner Bros Newline PRODUCTION DESIGNER Director: Andres Muschietti Starring : Bill Sasgard, Jaeden Lieberher, Sophia Lillis, Finn Wolfhard. THE ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO 3D FEATURE 2014-15 Paramount Overseas Pictures inc. China Film Group PRODUCTION DESIGNER (shoot postponed) Director: Rob Cohen Starring : TBA. THE AGE OF ADALINE FEATURE 2013-14 Lionsgate Lakeshore entertainment PRODUCTION DESIGNER Director: Lee T. Krieger Starring : Blake Lively, Harrison Ford, Ellen Burstyn. PERCY JACKSON AND THE OLYMPIANS THE SEA OF MONSTERS 3D FEATURE 2012 20TH Century Fox PRODUCTION DESIGNER Director: Thor Freudenthal Starring :.Logan Lerman, Stanley Tucci, Nathan Filion, Alexandra Diddario. UNDERWORLD : AWAKENING 3D FEATURE 2011 Screen Gems Lakeshore entertainment PRODUCTION DESIGNER Directors: Bjorn Stein, Mans Marlind Starring : Kate Beckinsale. Stephen Rea. 2 RISE OF THE PLANET OF THE APES FEATURE 2010 20TH Century Fox PRODUCTION DESIGNER Director: Rupert Wyatt Starring : James Franco, Andy Serkis, John Lightgow, Frieda Pinto. BARNEY’S VERSION FEATURE 2009 Serendipity Point Films Sony Pictures Classics PRODUCTION DESIGNER 2nd UNIT DIRECTOR Director: Richard J. Lewis Starring : Paul Giamatti, Dustin Hoffman, Minnie Driver, Rosemond Pike, Scott Speeman, Rachelle Lefebvre. *** Best Art Direction : Genie Awards Winner, DGC Awards Winner, Jutra Awards Nominee. *** NIGHT AT THE MUSEUM BATTLE OF THE SMITHSONIAN FEATURE 2007-08 20Th Century Fox PRODUCTION DESIGNER Director: Shawn Levy Starring : Ben Stiller, Robin Williams, Owen Wilson, Amy Adams, Christopher Guest, Ricky Gervais, Alain Chabat, Dick Van Dyke, Mickey Rooney. -

CREW Camera Operators and Camera Assistants Burgoon

CREW Camera Operators and Camera Assistants Burgoon, Brooks Camera Operator/AC [email protected] 949.370.3176 https://vimeo.com/brooksburgoon ESPN ENG Camera Operator for multiple television features. Has shot multiple low budget commercials and music videos using a RED camera. Assistant Cameraman for a reality tv show where fast-paced and intense scenarios are expected. Has shot multiple corporate events using my own professional audio equipment and DSLR package. Also an experienced FCP 7 editor specializing in color grading. Brooks Burgoon DIT/Data Wrangler [email protected] 949.370.3176 Was responsible for wrangling data for the feature, "Tab Hunter: Confidential". The footage was shot on a SONY F3 and to an AJA External recording device. Wrangled data for Panasonic Varicam, Arri Alexa, RED Camera, and DSLR's. Travels with Macbook Pro, G-Drive, 2 TB Drive for backup, CF cards and readers, and all necessary powering devices. FCP 7, WonderShare Converter, Quicktime, and VLC come with the computer. Freeman, Brian 1st Assistant / 2nd Assistant [email protected] 818.601.1282 After graduating UC Santa Barbara, Brian worked for two years at Panavision Hollywood as a Prep Tech prior to starting his freelance career. At Panavision, he worked with, trained on, prepped, serviced and cleaned all high end motion picture camera systems, lenses and accessories. Since then he has worked as both a 1st and 2nd Assistant on numerous features, shorts, music videos, web series and commercials. 35mm, 16mm, RED, Epic, Alexa, DSLR, Anamorphic Green, Eric J Camera operator for reality and documentary Camera Director 310.699.4416 Based out of Santa Barbara [email protected] 10+ years experience shooting mostly reality and documentary style. -

142 Filed 01/15/18 Entered 01/15/18 13:14:25 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 10

Case 17-29073 Doc 142 Filed 01/15/18 Entered 01/15/18 13:14:25 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 10 Debtor VidAngel, Inc. EIN 46-5217451 k Name United States Bankruptcy Court District of Utah Date case filed for chapter 11: 10/18/17 Case number: 17-29073 KRA Official Form 309F (For Corporations or Partnerships) (12/15) Notice of Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Case For the debtor listed above, a case has been filed under chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code. An order for relief has been entered. This notice has important information about the case for creditors, debtors, and trustees, including information about the meeting of creditors and deadlines. Read all pages carefully. The filing of the case imposed an automatic stay against most collection activities. This means that creditors generally may not take action to collect debts from the debtor or the debtor's property. For example, while the stay is in effect, creditors cannot sue, assert a deficiency, repossess property, or otherwise try to collect from the debtor. Creditors cannot demand repayment from the debtor by mail, phone, or otherwise. Creditors who violate the stay can be required to pay actual and punitive damages and attorneys fees. Confirmation of a chapter 11 plan may result in a discharge of debt. A creditor who wants to have a particular debt excepted from discharge may be required to file a complaint in the bankruptcy clerk's office within the deadline specified in this notice.(See line 11 below for more information.) To protect your rights, consult an attorney.