Evolution of Sizes and Industrial Structure of Cities in Japan from 1980 to 2010: Constant Churning and Persistent Regularity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using REIT Data to Assess the Economic Worth of Mega-Events: the Case of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Using REIT Data to Assess the Economic Worth of Mega-Events: The Case of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics Ogawa, Ryoh Osaka City University 1 May 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/78829/ MPRA Paper No. 78829, posted 01 May 2017 01:41 UTC Using REIT Data to Assess the Economic Worth of Mega-Events: The Case of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics Ryoh Ogawa∗ Osaka City University Abstract This paper proposes an alternative approach to evaluate the effects of hosting mega-events, such as the Olympics, Football World Cup, and World Expo. Based on capitalization hypothesis, previous literature studies examined whether the announcement of mega-events affects prices of firms’ stock or real estate property. In contrast, I utilize data on Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT), whose price has two features of stock and property price. The standard event study methodology with high-frequent data allows the estimation of abnormal returns due to the mega-event of interest, and clarifies the relationship between level of returns and characteristics of REIT’s property. I present an empirical example—the 2020 Tokyo Olympics—and the results are as follows: 1) investors judged that the comprehensive effects would be positive; 2) the effect becomes smaller as the distance from Host City (Tokyo-to) increases; 3) even in areas far from Tokyo-to, real estate used for hotels and commercial facilities are relatively susceptible to the Olympics. Keywords: mega-events; Olympic Games; Real Estate Investment Trust; event study ∗ Graduate School of Economics, Osaka City University; [email protected]; 3-3-138 Sugimoto Sumiyoshi- ku, Osaka-shi, 558-8585 JAPAN 1 1. -

Spatial Distribution of Economic Activities in Japan and China Masahisa Fujita, J

Spatial Distribution of Economic Activities in Japan and China Masahisa Fujita, J. Vernon Henderson, Yoshitsugu Kanemoto, Tomoya Mori July 9, 2003 1. Introduction (to be completed) 2. Distribution of Economic Activities in Japan The purpose of this section is to examine the distribution of economic activities in Japan. Rapid economic growth in the 20th century was accompanied by tremendous changes in spatial structure of activities. In Section 2.1, we examine the regional transformations that arose in postwar Japan. Roughly speaking, after WWⅡ the Japanese economy has experienced two phases of major structural changes. For our purpose, the interesting aspect is that each phase of industrial shift has been accompanied with a major transformation in the nationwide regional structure. The Japanese economy now seems to be in the midst of a third one and we offer some conjectures about its possible evolution. Perhaps the most important public policy issues concerning urban agglomeration in Japan is the Tokyo problem. Indeed, Tokyo is probably the largest metropolitan area in the world with a population exceeding 30 million. The dominance of Tokyo has increased steadily over the 20th century, ultimately absorbing a quarter of the Japanese population in 2000. In Section 2.2, we discuss attempts made to test empirically the hypothesis that Tokyo is too big. A test of this kind involves the estimation of urban agglomeration economies and we also review the empirical literature in this area. In Section 2.3, we move to the spatial distribution of industries among cities. Some metro areas have attracted a disproportionately large number of industries, leading to great variations in industrial diversity among metro areas. -

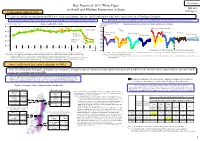

Key Factors of 2011 White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises In

Provisional Key Factors of 2011 White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan July, 2011 Trends among SMEs in 2010 SME Agency The business conditions and production of SMEs were beginning to improve, but have significantly worsened due to the impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake. The business conditions generally tended to improve, but have significantly worsened in March 2011 especially in East Japan. The production generally tended to improve, but has decreased in March 2011; the range of the decrease was the largest-ever. (Year-to-year basis: DI) Business condition DI of SMEs (Seasonal adjustment figure: Manufacturing production index by industry and by size of enterprise ▲ 2005=100) 30.0 160 Industry for electronic parts and All over Japan Steel ▲ 40.0 140 industry Manufacturing Transport Chemical Kanto & industry General machinery Food and cigarette Electric machine ▲ 50.0 Koshinetsu 120 Hokkaido & 100 ▲ 60.0 Tohoku 80 ▲ 70.0 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 2 3 4 60 10 11 Year/Month 40 Thick-lines represent SMEs and thin and dotted lines represent large Enterprises. Sources: “Survey of Monthly Business Conditions of Small and Medium Enterprises” by National Federation of Small Business Associations Sources: METI, “Indices of Industrial Production” and “Current Production Statistics Survey”; and SME Agency, “Manufacturing Production Indices by Size of Enterprises” Notes:1. Survey was conducted by the information liaison members appointed at the Prefectural Central Federations (About 2,700 executives and Notes:1. The term is from January 2008 to April 2011. employees of SME associations (such as cooperatives and commercial associations) are assigned to the survey). -

Chapter 6 Urban Employment Areas: Defining Japanese

CHAPTER 6 URBAN EMPLOYMENT AREAS: DEFINING JAPANESE METROPOLITAN AREAS AND CONSTRUCTING THE STATISTICAL DATABASE FOR THEM Yoshitsugu Kanemoto Graduate School of Public Policy and Graduate School of Economics, University of Tokyo Reiji Kurima Project Researcher, Research Center for the Relationship Between Market Economy and Non-Market Institutions, Graduate School of Economics, University of Tokyo 6.1 INTRODUCTION For those interested in analyzing urban activity, the first task should be to define urban areas. The legal definition of a city is a natural starting point, but many urban activities extend beyond jurisdictional boundaries. For example, many workers in large metropolitan areas commute from suburban jurisdictions to central cities. We therefore need a definition of an urban area within which most everyday activities are undertaken. An urban area typically comprises a core area that has significant concentrations of employment, which is surrounded by densely settled areas that have close commuting ties to the core. 1 In the United States, the Federal Government has defined metropolitan areas since 1947 and provides a variety of statistical data relating to them. There is no counterpart in Japan, and the only definitions of metropolitan areas available are those proposed by a small number of researchers. Most of these adopt standards similar to the Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA), which was in use in the 1960s and 1970s. However, in the U.S., two major changes have occurred since then, which reflect changes in the population distribution and activity patterns. First, in the 1980s, the Consolidated Metropolitan Statistical Area (CMSA) was introduced, which connects metropolitan areas that have significant interactions. -

Department of Urban Science and Policy 2018FY Annual Report

Department of Urban Science and Policy 2018FY Annual Report ■ Staff List of the Department of Urban Science and Policy, Faculty of Urban Environmental Sciences (in alphabetical order of the family name) Shin AIBA, Professor Chisato ASAHI, Professor Taro ICHIKO, Professor Fumiko ITOH, Professor Akira KANEKO, Associate Professor Nozomi MATSUI, Professor Motoi NAGANO, Associate Professor Shigemi, OTSUKI, Assistant Professor Mami OKU, Professor Ken SHIRAISHI, Professor Yoko SUGUHARA, Associate Professor Masashi TAKAMICHI, Assistant Professor Hidenori TAMAGAWA, Professor Kiyomi WADA, Professor Kahoruko YAMAMOTO, Associate Professor Assistant Professor Otsuki transferred to Juntendo University in April, 2019. << Shin AIBA >> 1) Staff Shin AIBA Associate Professor/Dr. Eng. Urban Planning, Machizukuri Rm.9-566, +81 426 77 1111 Ext.4237 [email protected] 2) Overview of Research Activities in 2014FY 1. Study on reconstruction from disaster Shin AIBA I studied on reconstruction plans and projects from Great East Japan earthquake. I supported to plan reconstruction projects and conducted an experiment to leave lessons and memories of disaster in Ryori village, Ofunato city. Results were published on academic magazines. 2. Urbanism on population decreasing age Shin Aiba I discussed and examined a theory of urban planning and design on population decreasing age. I gave advices on making city plan to some local government ( Fukushima city, Hino city and Kobe city).And I also conducted a planning project to utilize abandoned house in a district of Hino city. Results are published on some articles. 3. Comparative study on machizukuri in east Asian countries Shin Aiba I researched community design projects in Republic of China and urban regeneration policy in South Korea comparing policy, history and practice of machizukuri in Japan, Taiwan and Korea. -

GDP (By Industry)

Asian Economy and Regional Economy in Japan What is the situation of industrial structure? ■国土のモニタリング GDP (by industry) GDP and Employment data shows that the share of the service sector has increased in resent years. The share of manufacturing and construction sector has decreased in term of GDP, and been flat in term of employment number. GDP (by industry) Employment (by industry) 100% 100% 75% 75% other sector service sector 50% 50% construction sector manufacturing sector 25% 25% 0% 0% (year) 1970 1980 1990 1995 2001 2002 2003 (year) 1970 1980 1990 1995 2001 2002 2003 Asian Economy and Regional Economy in Japan What is the situation of industrial structure? ■国土のモニタリング Employment growth rate (by industry) The number of employed persons throughout all industries has continued to decline since 1995 in both the rural and the three metropolitan areas. In particular, the number of persons employed by the manufacturing sector in both the rural and the three metropolitan areas has been decreasing since 1990s and the number of persons employed by the construction sector in both the rural and the three metropolitan areas has been decreasing since 1995. In contrast, although its growth has been dulled recently, the service sector has continued to hire since 1995 in both the rural and the three metropolitan areas. Number of employed persons in both the rural and the three metropolitan areas (%) All industries (%) Manufacturing sector 20 20 15 the three major urban economic spheres 15 10 10 5 the rural economic 0 5 spheres -5 建設業 0 the rural economic -

20190410 Japanese Explorer

Japanese Explorer Wednesday, 10 Apr 2019 & Thursday, 11 Apr 2019 Up early this morning, it is a travel day. We changed the bed and reset the hotel. Then we had a light smoothie for breakfast. The drive to AeroParking was busy with traffic but once it cleared downtown Tacoma the drive was smooth. We were on our way to the terminal. Second in line, the clerks would not open the counter for twenty minutes. In the meantime, I went to the electronic check-in terminal to print luggage tags. Then a line of agents arrived and lined up in a front of a dozen young women in All Nippon Airline uniforms. They were all young but one seemed to be the “lieutenant” in charge and she announced they wished us to welcome us to ANA and then they 355 all bowed in greeting before taking their places behind the counter. They processed us in quickly and moved Liz and me to seats further up in the aircraft. Then we continued to the South Terminal and sat down in the gate area. Once we boarded we observed a very efficient and professional crew who made us quite comfortable. Showing a movie, we saw several people in traditional white-face make up and theater worthy Japanese costumes. They explained safety procedures in a highly delightful way. Later, as we departed the aircraft, they showed the filming of the exercise with the application of make-up, costumes, and cameramen recording the process. Very clever! We departed on time at 13:20 and, thanks to crossing the International Date Line, we arrived after the nine hour flight at 15:30 the next day. -

Regional Employment and Artificial Intelligence in Japan

DPRIETI Discussion Paper Series 18-E-032 Regional Employment and Artificial Intelligence in Japan HAMAGUCHI Nobuaki RIETI KONDO Keisuke RIETI The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/ RIETI Discussion Paper Series 18-E-032 May 2018 Regional Employment and Artificial Intelligence in Japan* HAMAGUCHI Nobuaki † KONDO Keisuke ‡ RIEB, Kobe University RIETI RIETI Abstract This study investigates employment risk caused by new technology, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, using the probability of computerization by Frey and Osborne (2017) and Japanese employment data. The new perspective of this study is the consideration of regional heterogeneity in labor markets due to the uneven geographical distribution of occupations, which is especially observed between male and female workers. This study finds that female workers are exposed to higher risks of computerization than male workers, since they tend to be engaged in occupations with a high probability of computerization. This tendency is more pronounced in larger cities. Our results suggest that supporting additional human capital investment alone is not enough as a risk alleviation strategy against new technology, and policymakers need to address structural labor market issues, such as gender biases for career progression and participation in decision-making positions, in the AI era to mitigate unequal risk of computerization between workers. JEL classification: J24, J31, J62, O33, R11 Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Computerization, Automation, Employment, Gender gap RIETI Discussion Papers Series aims at widely disseminating research results in the form of professional papers, thereby stimulating lively discussion. The views expressed in the papers are solely those of the author(s), and neither represent those of the organization to which the author(s) belong(s) nor the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry. -

Commuting Zones in Japan

Commuting Zones in Japan By Daisuke Adachi(Yale University and RIETI) Taiyo Fukai(Cabinet Office and The University of Tokyo) Daiji Kawaguchi (The University of Tokyo, RIETI and IZA) Yukiko U. Saito (Waseda University and RIETI) November 2020 CREPE DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 85 CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND EDUCATION FOR POLICY EVALUATION (CREPE) THE UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO http://www.crepe.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ Commuting Zones in Japan∗ Daisuke Adachi† Taiyo Fukai‡ Daiji Kawaguchi§ Yukiko U. Saito¶ November 19, 2020 Abstract Choosing a proper geographic unit is crucial for achieving an accurate analysis of local labor markets. While a small administrative unit such as the municipality is not always ideal because workers commute across units to form a single labor market, a large administrative unit such as the prefecture is often too coarse because prefectures typically include several labor markets. To define appropriate local labor markets for Japan, we first constructed commuting zones (CZs) using the commuting patterns observed in the Population Census from 1980 to 2015 and the hierarchical agglomerative clustering method adopted by Tolbert and Sizer (1996) to delineate CZs in the US. From 1,736 municipalities in 2015, for example, we constructed 265 CZs that are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. We then compared the properties of CZs ∗This study was conducted under the "Dynamics of Inter-organizational Network and Firm Life Cycle" project of the Japan Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) and financially supported by grants from the Japan Science and Technology Agency’s Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society (JPMJRX18H3) and from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI Grant Number 15H05692; PI: Hidehiko Ichimura). -

Managing Conflicts with Local Communities Over The

land Article Managing Conflicts with Local Communities over the Introduction of Renewable Energy: The Solar-Rush Experience in Japan Noriko Akita 1,* , Yasuo Ohe 2 , Shoko Araki 1 , Makoto Yokohari 3, Toru Terada 4 and Jay Bolthouse 5 1 Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University, Matsudo City, Chiba 271-8510, Japan; [email protected] 2 Faculty of International Agriculture and Food Studies, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 156-8502, Japan; [email protected] 3 Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8656, Japan; [email protected] 4 Graduate School of Frontier Science, The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa City, Chiba 277-8561, Japan; [email protected] 5 Independent Researcher, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8656, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-47-308-8931 Received: 6 July 2020; Accepted: 19 August 2020; Published: 23 August 2020 Abstract: A worldwide introduction of renewable energy has been required to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Concomitantly, this has caused conflict between renewable energy development and local communities over landscape changes. This study aims to clarify the factors of conflict and find a way of conflict management. A case study on Japan is used, where a solar rush occurred due to the feed-in tariff (FIT) system. We analyze the public reasons to worry about renewable energy and the spatial characteristics of its locations. A socio-spatial approach is used by first utilizing a qualitative survey based on questionnaires and interviews with the local governments to understand the awareness regarding the issues, and then utilizing a quantitative survey on the location changes to solar power by using GIS. -

Regional Differences in the Socio-Economic and Built-Environment Factors

Urban and Regional Planning Review Vol. 4, 2017 | 251 Regional Differences in the Socio-economic and Built-environment Factors of Vacant House Ratio as a Key Indicator for Spatial Urban Shrinkage Hiroki Baba* and Yasushi Asami** Abstract The phenomenon of urban shrinkage is surging through cities in Japan. To understand the current situation of urban shrinkage in Japan, the number of vacant housing would be one of the key indicators. The purpose of the study is to clarify the regional differences in the socio-economic and built-environment factors of vacant house ratio as a key indicator for spatial urban shrinkage. The characteristics of cities are identified by means of socio-economic and built-environment factors, which enable us to describe the current situation of spatial urban shrinkage more precisely. In this analysis, 771 cities in Japan are original units in order to articulate the geographical differences in urban shrinkage. To differentiate regions, we classified cities according to urban employment area (UEA) into 4 categories. Using 7 socio-economic and built-environment variables, a general linear mixed model was employed to clarify the statistical significances in each UEA category. The key findings were as follows. First, strong trends of vacant house ratio and its factors among categories were found. Second, socio-economic factors affecting vacant house ratio in each category were statistically significant in all the categories. Third, built- environment factors also had a clear relationship with vacant house ratio, but the influences varied among the four categories. Finally, in order to prepare for future spatial urban shrinkage, areas of anticipated spatial urban shrinkage were identified from the results of the study. -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033055 on 6 August 2020. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on October 3, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033055 on 6 August 2020. Downloaded from Temporal trends and geographical disparities in comprehensive stroke center capabilities in Japan from 2010 to 2018 ForJournal: peerBMJ Open review only Manuscript ID bmjopen-2019-033055 Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the 22-Jul-2019 Author: Complete List of Authors: KUROGI, AI; Graduate School of