Chord-Specific Scalar Material in Classical Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Jazz Chord Symbols Here I Use the More Explicit Abbreviation 'Maj7' for Major Seventh

Common jazz chord symbols Here I use the more explicit abbreviation 'maj7' for major seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C² C²7 CMA7 and CM7. Here I use the abbreviation 'm7' for minor seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C- C-7 Cmi7 and Cmin7. The variations given for Major 6th, Major 7th, Dominant 7th, basic altered dominant and minor 7th chords in the first five systems are essentially interchangeable, in other words, the 'color tones' shown added to these chords (9 and 13 on major and dominant seventh chords, 9, 13 and 11 on minor seventh chords) are commonly added even when not included in a chord symbol. For example, a chord notated Cmaj7 is often played with an added 6th and/or 9th, etc. Note that the 11th is not one of the basic color tones added to major and dominant 7th chords. Only #11 is added to these chords, which implies a different scale (lydian rather than major on maj7, lydian dominant rather than the 'seventh scale' on dominant 7th chords.) Although color tones above the seventh are sometimes added to the m7b5 chord, this chord is shown here without color tones, as it is often played without them, especially when a more basic approach is being taken to the minor ii-V-I. Note that the abbreviations Cmaj9, Cmaj13, C9, C13, Cm9 and Cm13 imply that the seventh is included. Major triad Major 6th chords C C6 C% w ww & w w w Major 7th chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and 7th of root's major scale) 4 CŒ„Š7 CŒ„Š9 CŒ„Š13 w w w w & w w w Dominant seventh chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and b7 of root's major scale) 7 C7 C9 C13 w bw bw bw & w w w basic altered dominant 7th chords 10 C7(b9) C7(#5) (aka C7+5 or C+7) C7[äÁ] bbw bw b bw & w # w # w Minor 7 flat 5, aka 'half diminished' fully diminished Minor seventh chords (root, b3, b5, b7). -

How to Navigate Chord Changes by Austin Vickrey (Masterclass for Clearwater Jazz Holiday Master Sessions 4/22/21) Overview

How to Navigate Chord Changes By Austin Vickrey (Masterclass for Clearwater Jazz Holiday Master Sessions 4/22/21) Overview • What are chord changes? • Chord basics: Construction, types/qualities • Chords & Scales and how they work together • Learning your chords • Approaches to improvising over chords • Arpeggios, scales, chord tones, guide tones, connecting notes, resolutions • Thinking outside the box: techniques and exercises to enhance and “spice up” your improvisation over chords What are “chord changes?” • The series of musical chords that make up the harmony to support the melody of a song or part of a song (solo section). • The word “changes” refers to the chord “progression,” the original term. In the jazz world, we call them changes because they typically change chord quality from one chord to the next as the song is played. (We will discuss what I mean by “quality” later.) • Most chord progressions in songs tend to repeat the series over and over for improvisors to play solos and melodies. • Chord changes in jazz can be any length. Most tunes we solo over have a form with a certain number of measures (8, 12, 16, 24, 32, etc.). What makes up a chord? • A “chord" is defined as three or more musical pitches (notes) sounding at the same time. • The sonority of a chord depends on how these pitches are specifically arranged or “stacked.” • Consonant chords - chords that sound “pleasing” to the ear • Dissonant chords - chords that do not sound “pleasing” to the ear Basic Common Chord Types • Triad - 3 note chord arranged in thirds • Lowest note - Root, middle note - 3rd, highest note - 5th. -

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

Eduqas-Bach-Badinerie-Musical-Analysis.Pdf

Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie J.S.Bach: BADINERIE from Orchestral Suite No.2 Melodic Analysis The entire movement is based on two musical motifs: X and Y. Section A Bars 02 – 161 Sixteen bars Bars 02 – 21 The movement opens with the first statement of motif X, which is played by the flute. The motif is a descending B minor arpeggio/broken chord with a characteristic quaver and semiquaver(s) rhythm. Bars 22 – 41 The melodic material remains with the flute for the first statement of motif Y. This motifis an ascending semiquaver figure consisting of both arpeggios/broken chords sand conjunct movement. Bars 42 – 61 Motif X is then restated by the flute. Music | Bach: Badinerie - Musical Analysis 1 Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie Bars 62 – 81 Motif X is presented by the cellos in a slightly modified version in which the last crotchet of the motif is replaced with a quaver and two semiquavers. This motif moves the tonality to A major and is also the initial phrase in a musical sequence. Bars 82 – 101 Motif X remains with the cellos with a further modified ending in which the last crotchet is replaced with four semiquavers. It moves the tonality to the dominant minor, F# minor, and is the answering phrase in a musical sequence that began in bar 62. Bars 102 – 121 Motif Y returns in the flute part with a modified ending in which the last two quavers are replaced by four semiquavers. Bars 122 – 161 The flute continues to present the main melodic material. Motif Y is both extended and developed, and Section A is brought to a close in F# minor. -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Spring 2015 The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók David B. Hill James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Hill, David B., "The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók" (2015). Dissertations. 38. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/38 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill A document submitted to the graduate faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music May 2015 ! TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! ! Figures…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…iii! ! Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...iv! ! Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1! ! PART!I:!SIMILARITIES!SHARED!BY!THE!TWO!NATIONLISTIC!COMPOSERS! ! A.!Origins…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4! ! B.!Ties!to!Hungary…………………………………………………………………………………………...…..9! -

Introduction to Music Theory

Introduction to Music Theory This pdf is a good starting point for those who are unfamiliar with some of the key concepts of music theory. Reading musical notation Musical notation (also called a score) is a visual representation of the pitched notes heard in a piece of music represented by dots over a set of horizontal staves. In the top example the symbol to the left of the notes is called a treble clef and in the bottom example is called a bass clef. People often like to use a mnemonic to help remember the order of notes on each clef, here is an example. Intervals An interval is the difference in pitch between two notes as defined by the distance between the two notes. The easiest way to visualise this distance is by thinking of the notes on a piano keyboard. For example, on a C major scale, the interval from C to E is a 3rd and the interval from C to G is a 5th. Click here for some more interval examples. It is also common for an increase by one interval to be called a halfstep, or semitone, and an increase by two intervals to be called a whole step, or tone. Joe ReesJones, University of York, Department of Electronics 19/08/2016 Major and minor scales A scale is a set of notes from which melodies and harmonies are constructed. There are two main subgroups of scales: Major and minor. The type of scale is dependant on the intervals between the notes: Major scale Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone Minor scale Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone For example (by visualising a keyboard) the notes in C Major are: CDEFGAB, and C Minor are: CDE♭FGA♭B♭. -

Orientalism As Represented in the Selected Piano Works by Claude Debussy

Chapter 4 ORIENTALISM AS REPRESENTED IN THE SELECTED PIANO WORKS BY CLAUDE DEBUSSY A prominent English scholar of French music, Roy Howat, claimed that, out of the many composers who were attracted by the Orient as subject matter, “Debussy is the one who made much of it his own language, even identity.”55 Debussy and Hahn, despite being in the same social circle, never pursued an amicable relationship.56 Even while keeping their distance, both composers were somewhat aware of the other’s career. Hahn, in a public statement from 1890, praised highly Debussy’s musical artistry in L'Apres- midi d'un faune.57 Debussy’s Exposure to Oriental Cultures Debussy’s first exposure to oriental art and philosophy began at Mallarmé’s Symbolist gatherings he frequented in 1887 upon his return to Paris from Rome.58 At the Universal Exposition of 1889, he had his first experience in the theater of Annam (Vietnam) and the Javanese Gamelan orchestra (Indonesia), which is said to be a catalyst 55Roy Howat, The Art of French Piano Music: Debussy, Ravel, Fauré, Chabrier (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 110 56Gavoty, 142. 57Ibid., 146. 58François Lesure and Roy Howat. "Debussy, Claude." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/07353 (accessed April 4, 2011). 33 34 in his artistic direction. 59 In 1890, Debussy was acquainted with Edmond Bailly, esoteric and oriental scholar, who took part in publishing and selling some of Debussy’s music at his bookstore L’Art Indépendeant. 60 In 1902, Debussy met Louis Laloy, an ethnomusicologist and music critic who eventually became Debussy’s most trusted friend and encouraged his use of Oriental themes.61 After the Universal Exposition in 1889, Debussy had another opportunity to listen to a Gamelan orchestra 11 years later in 1900. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

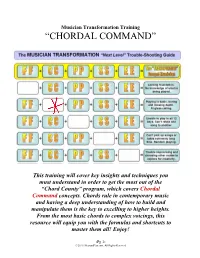

“Chordal Command”

Musician Transformation Training “CHORDAL COMMAND” This training will cover key insights and techniques you must understand in order to get the most out of the “Chord County” program, which covers Chordal Command concepts. Chords rule in contemporary music and having a deep understanding of how to build and manipulate them is the key to excelling to higher heights. From the most basic chords to complex voicings, this resource will equip you with the formulas and shortcuts to master them all! Enjoy! -Pg 1- © 2010. HearandPlay.com. All Rights Reserved Introduction In this guide, we’ll be starting with triads and what I call the “FANTASTIC FOUR.” Then we’ll move on to shortcuts that will help you master extended chords (the heart of contemporary playing). After that, we’ll discuss inversions (the key to multiplying your chordal vocaluary), primary vs secondary chords, and we’ll end on voicings and the difference between “voicings” and “inversions.” But first, let’s turn to some common problems musicians encounter when it comes to chordal mastery. Common Problems 1. Lack of chordal knowledge beyond triads: Musicians who fall into this category simply have never reached outside of the basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) and are stuck playing the same chords they’ve always played. There is a mental block that almost prohibits them from learning and retaining new chords. Extra effort must be made to embrace new chords, no matter how difficult and unusual they are at first. Knowing the chord formulas and shortcuts that will turn any basic triad into an extended chord is the secret. -

Scale Essentials for Bass Guitar Course Breakdown

Scale Essentials For Bass Guitar Course Breakdown Volume 1: Scale Fundamentals Lesson 1-0 Introduction In this lesson we look ahead to the Scale Essentials course and the topics we’ll be covering in volume 1 Lesson 1-1 Scale Basics What scales are and how we use them in our music. This includes a look at everything from musical keys to melodies, bass lines and chords. Lesson 1-2 The Major Scale Let’s look at the most common scale in general use: The Major Scale. We’ll look at its construction and how to play it on the bass. Lesson 1-3 Scale Degrees & Intervals Intervals are the building blocks of music and the key to understanding everything that follows in this course Lesson 1-4 Abbreviated Scale Notation Describing scales in terms of complete intervals can be a little long-winded. In this lesson we look at a method for abbreviating the intervals within a scale. Lesson 1-5 Cycle Of Fourths The cycle of fourths is not only essential to understanding key signatures but is also a great system for practicing scales in every key Lesson 1-6 Technique Scales are a common resource for working on your bass technique. In this lesson we deep dive into both left and right hand technique Lesson 1-7 Keys & Tonality Let’s look at the theory behind keys, the tonal system and how scales fit into all of this Lesson 1-8 Triads Chords and chord tones will feature throughout this course so let’s take a look at the chord we use as our basic foundation: The Triad Lesson 1-9 Seventh Chords After working on triads, we can add another note into the mix and create a set of Seventh Chords Lesson 1-10 Chords Of The Major Key Now we understand the basics of chord construction we can generate a set of chords from our Major Scale.