Media, Civil Rights, and American Collective Memory a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED to the FACULTY OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media, Civil Rights, and American Collective Memory A

Committing a Movement to Memory: Media, Civil Rights, and American Collective Memory A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Meagan A. Manning IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Catherine R. Squires June 2015 © Meagan A. Manning, 2015 Acknowledgements This dissertation was completed over the course of several years, many coffee shop visits, and residence in several states. First and foremost, I would like to thank my adviser Dr. Catherine R. Squires for her wisdom, support, and guidance throughout this dissertation and my entire academic career. I would also like to thank my committee members, Drs. Tom Wolfe, David Pellow, and Shayla Thiel-Stern for their continued dedication to the completion of this project. Each member added a great deal of their own expertise to this research, and it certainly would not be what it is today without their contribution. I would also like to thank the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota for allowing me the opportunity to pursue graduate studies in Communication. A big thank you to the graduate student community at the SJMC is also in order. Thanks also to my family and friends for the pep talks, smiles, hugs and interest in my work. Finally, thank you to Emancipator, Bonobo, and Tacocat for getting me through all of those long days and late nights. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to Margaret and Edward Manning, Elvina and Edward Buckley and Edward Manning, Jr. and Gerard Manning, both of whom the universe took far too soon. -

2020 Annual Symposium Program Guide

2020 Program Guide Session Descriptions and Speaker Biographies Friday, August 28 – Saturday, August 29 Contents Gloria and John L. Academic Symposium Opening Keynote Speaker 3 Closing Keynote Speaker 5 Concurrent Sessions Session I – Allies and Blazers 7 Session II - Coping in Times of Crisis: Your Mental Wellbeing 10 Session III - The Next Generation of Civil Rights Leaders 11 Session IV - Managing a Pandemic within a Pandemic. 13 Session V - Judge Frank Johnson's Role Upholding the Constitution 15 Session VI - Keeping Inherent Bias Out of Decision Making 16 Session VII - Community-based Alternatives to Prison in Alabama 17 Session VIII - Weaponizing One's Whiteness (for Good): Proactive Allyship 19 Session IX - Public Leadership in a Time of COVID-19 22 Session X - Covering Politics in a Time of Crisis 25 Session XI - Race Relations 2020: The Conversation... 28 Session XII - The Resilient Leader: Taking Care of Yourself so You Can Take Care of Others 29 Session XIII - Leading in Uncomfortable Spaces 30 Session XIV - Leading on Racial Equity amid Social Unrest 33 Session XV - The Fight for the Noblest Democracy: Women's Suffrage in Alabama 36 Session XVI - Student Leadership During a Time of Crisis 37 Session XVII - Public Health Communication during a Pandemic 41 Session XVIII - The Tuscaloosa Civil Rights History and Reconciliation Foundation 43 Page 2 Opening Keynote Speaker – 4:30pm, Friday Dr. Selwyn Vickers, Professor Senior Vice President of Medicine, UAB Dean, UAB School of Medicine Selwyn M. Vickers, MD, is Senior Vice President of Medicine and Dean of The University of Alabama School of Medicine, one of the ten largest public academic medical centers and the third largest public hospital in the USA. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

Selected Chronology of Political Protests and Events in Lawrence

SELECTED CHRONOLOGY OF POLITICAL PROTESTS AND EVENTS IN LAWRENCE 1960-1973 By Clark H. Coan January 1, 2001 LAV1tRE ~\JCE~ ~')lJ~3lj(~ ~~JGR§~~Frlt 707 Vf~ f·1~J1()NT .STFie~:T LA1JVi~f:NCE! i(At.. lSAG GG044 INTRODUCTION Civil Rights & Black Power Movements. Lawrence, the Free State or anti-slavery capital of Kansas during Bleeding Kansas, was dubbed the "Cradle of Liberty" by Abraham Lincoln. Partly due to this reputation, a vibrant Black community developed in the town in the years following the Civil War. White Lawrencians were fairly tolerant of Black people during this period, though three Black men were lynched from the Kaw River Bridge in 1882 during an economic depression in Lawrence. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1894 that "separate but equal" was constitutional, racial attitudes hardened. Gradually Jim Crow segregation was instituted in the former bastion of freedom with many facilities becoming segregated around the time Black Poet Laureate Langston Hughes lived in the dty-asa child. Then in the 1920s a Ku Klux Klan rally with a burning cross was attended by 2,000 hooded participants near Centennial Park. Racial discrimination subsequently became rampant and segregation solidified. Change was in the air after World "vV ar II. The Lawrence League for the Practice of Democracy (LLPD) formed in 1945 and was in the vanguard of Post-war efforts to end racial segregation and discrimination. This was a bi-racial group composed of many KU faculty and Lawrence residents. A chapter of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) formed in Lawrence in 1947 and on April 15 of the following year, 25 members held a sit-in at Brick's Cafe to force it to serve everyone equally. -

Black Vote Remains Crucial "I'm an Atheist and I'd Go to by D

AUGUST 2016 HEALTH WELLNESS & NUTRITION SUPPLEMENT EYE HEALTH AND IMMUNIZATION VOL. 51, NO. 44 • AUGUST 11 - 17, 2016 PRESENTED BY WI Health SupplementSPONSORS Pressure Leads to Councilman Orange’s Early Resignation - Hot Topics, Page 4 Center Section Rev. Barber First Day of Moving Forward, School Comes Before and After Early for Some DNC Convention D.C. Students By William J. Ford WI Staff Writer @jabariwill A pep-rally atmosphere greet- ed students and parents Mon- day, Aug. 8 at Turner Elementary School in southeast D.C. to begin the first day of school — a day that came a full two weeks earlier than for most of the city. Turner is one of 10 city schools taking part in the District's ex- 5Rev. William Barber II / Photo tended-school year, in which 20 by Shevry Lassiter extra days have been added for By Stacy M. Brown schools with at least 55 percent WI Senior Writer of its students not fully meeting expectations on the English and The headlines blared almost non- math portions of standardized as- stop. sessment tests in the 2014-2015 "Rev. William Barber Rattles the academic year. Windows, Shakes the DNC Walls," During that year, Turner had one of the lowest rankings among NBC News said. 5Turner Elementary School Principal Eric Bethel greets a student on Aug. 8, the first day of the extended school year for D.C. "The Rev. William Barber public schools. Turner is one of 10 schools to partake in the program to boost student achievement. / Photo by William J. Ford DCPS Page 8 dropped the mic," The Washington Post marveled. -

History of Civil Rights in the United States: a Bibliography of Resources in the Erwin Library, Wayne Community College

History of Civil Rights in the United States: A Bibliography of Resources in the Erwin Library, Wayne Community College The History of civil rights in the United States is not limited in any way to the struggle to first abolish slavery and then the iniquitous “Jim Crow” laws which became a second enslavement after the end of the American Civil War in 1865. Yet, since that struggle has been so tragically highlighted with such long turmoil and extremes of violence, it has become, ironically perhaps, the source of the country’s greatest triumph, as well as its greatest shame. The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, who would have sought to guide the reunion of the warring states with a leniency and clear purpose which could possibly have prevented the bitterness that gave rise to the “Jim Crow” aberrations in the Southern communities, seems to have foreshadowed the renewed turmoil after the assassination in 1968 of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had labored so long to awaken the nation non-violently, but unwaveringly, to its need to reform its laws and attitudes toward the true union of all citizens of the United States, regardless of color. In 2014, we are only a year past the observation of two significant anniversaries in 2013: the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, re-focusing the flagging Union’s purpose on the abolition of slavery as an outcome of the Civil War, and the 50th anniversary of the “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. -

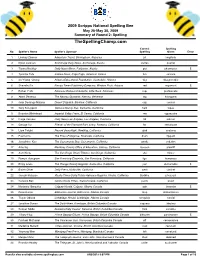

Round 2: Spelling Thespellingchamp.Com

2009 Scripps National Spelling Bee May 28-May 30, 2009 Summary of Round 2: Spelling TheSpellingChamp.com Correct Spelling No. Speller's Name Speller's Sponsor Spelling Given Error 1 Lindsey Zimmer Adventure Travel, Birmingham, Alabama jet longitude 2 Dylan Jackson Anchorage Daily News, Anchorage, Alaska sorites quarrel 3 Tianna Beckley Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks, Alaska got pharmecist E 4 Tynishia Tufu Samoa News, Pago Pago, American Samoa fun concise 5 So-Young Chung Arizona Educational Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona wig disagreeable 6 Shevelle Six Navajo Times Publishing Company, Window Rock, Arizona red regamont E 7 Esther Park Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Little Rock, Arkansas nap promenade 8 Abeni Deveaux The Nassau Guardian, Nassau, Bahamas leg hexagonal 9 Juan Domingo Malana Desert Dispatch, Barstow, California cup census 10 Cory Klingsporn Ventura County Star, Camarillo, California ham topaz 11 Brandon Whitehead Imperial Valley Press, El Centro, California see oppressive 12 Paige Vasseur Daily News Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California lid pelican 13 George Liu Friends of the Diamond Bar Library, Pomona, California far reevaluate 14 Liam Twight Record Searchlight, Redding, California glad anatomy 15 Paul Uzzo The Press-Enterprise, Riverside, California drum flippant 16 Josephine Kao The Sacramento Bee, Sacramento, California syndic sedative 17 Amy Ng Monterey County Office of Education, Salinas, California laocoon plaintiff 18 Alex Wells The San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego, California she mince 19 Ramya Auroprem San Francisco -

The Business Issue

VOL. 52, NO. 06 • NOVEMBER 24 - 30, 2016 Don't Miss the WI Bridge Trump Seeks Apology as ‘Hamilton’ Cast Challenges Pence - Hot Topics/Page 4 The BusinessCenter Section Issue NOVEMBER 2016 | VOL 2, ISSUE 10 Protests Continue Ahead of Trump Presidency By Stacy M. Brown cles published on Breitbart, the con- WI Senior Writer servative news website he oversaw, ABC News reported. The fallout for African Americans, President Barack Obama, the na- Muslims, Latinos and other mi- tion's first African-American presi- norities over the election of Donald dent, said Trump had "tapped into Trump as president has continued a troubling strain" in the country to with ongoing protests around the help him win the election, which has nation. led to unprecedented protests and Trump, the New York business- even a push led by some celebrities man who won more Electoral Col- to get the electorate to change its vote lege votes than Democrat Hillary when the official voting takes place on Clinton in the Nov. 8 election, has Dec. 19. managed to make matters worse by A Change.org petition, which has naming former Breitbart News chief now been signed by more than 4.3 Stephen Bannon as his chief strategist. million people, encourages members Bannon has been accused by many of the Electoral College to cast their critics of peddling or being complicit votes for Hillary Clinton when the 5 Imam Talib Shareef of Masjid Muhammad, The Nation's Mosque, stands with dozens of Christians, Jewish in white supremacy, anti-Semitism leaders and Muslims to address recent hate crimes and discrimination against Muslims during a news conference and sexism in interviews and in arti- TRUMP Page 30 before daily prayer on Friday, Nov. -

Freedom Riders Democracy in Action a Study Guide to Accompany the Film Freedom Riders Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation

DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover art credits: Courtesy of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Back cover art credits: Bettmann/CORBIS. To download a PDF of this guide free of charge, please visit www.facinghistory.org/freedomriders or www.pbs.org/freedomriders. ISBN-13: 978-0-9819543-9-4 ISBN-10: 0-9819543-9-1 Facing History and Ourselves Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445-6919 ABOUT FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES Facing History and Ourselves is a nonprofit and the steps leading to the Holocaust—the educational organization whose mission is to most documented case of twentieth-century engage students of diverse backgrounds in an indifference, de-humanization, hatred, racism, examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism antisemitism, and mass murder. It goes on to in order to promote a more humane and explore difficult questions of judgment, memory, informed citizenry. As the name Facing History and legacy, and the necessity for responsible and Ourselves implies, the organization helps participation to prevent injustice. Facing History teachers and their students make the essential and Ourselves then returns to the theme of civic connections between history and the moral participation to examine stories of individuals, choices they confront in their own lives, and offers groups, and nations who have worked to build a framework and a vocabulary for analyzing the just and inclusive communities and whose stories meaning and responsibility of citizenship and the illuminate the courage, compassion, and political tools to recognize bigotry and indifference in their will that are needed to protect democracy today own worlds. -

ED350369.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 369 UD 028 888 TITLE Introducing African American Role Models into Mathematics and Science Lesson Plans: Grades K-6. INSTITUTION American Univ., Washington, DC. Mid-Atlantic Equity Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 313p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; *Black Achievement; Black History; Black Students; *Classroom Techniques; Cultural Awareness; Curriculum Development; Elementary Education; Instructional Materials; Intermediate Grades; Lesson Plans; *Mathematics Instruction; Minority Groups; *Role Models; *Science Instruction; Student Attitudes; Teaching Guides IDENfIFIERS *African Americans ABSTRACT This guide presents lesson plans, with handouts, biographical sketches, and teaching guides, which show ways of integrating African American role models into mathematics and science lessons in kindergarten through grade 6. The guide is divided into mathematics and science sections, which each are subdivided into groupings: kindergarten through grade 2, grades 3 and 4, and grades 5 and 6. Many of the lessons can be adjusted for other grade levels. Each lesson has the following nine components:(1) concept statement; (2) instructional objectives;(3) male and female African American role models;(4) affective factors;(5) materials;(6) vocabulary; (7) teaching procedures;(8) follow-up activities; and (9) resources. The lesson plans are designed to supplement teacher-designed and textbook lessons, encourage teachers to integrate black history in their classrooms, assist students in developing an appreciation for the cultural heritage of others, elevate black students' self-esteem by presenting positive role models, and address affective factors that contribute to the achievement of blacks and other minority students in mathematics and science. -

Betty Lawson Conducted by Hilary Jones 11:30A.M., December 1, 2015 First African Baptist Church Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Interview with Ms. Betty Lawson Conducted by Hilary Jones 11:30A.M., December 1, 2015 First African Baptist Church Tuscaloosa, Alabama Ms. Betty Lawson was born in Hartford, Alabama, in Geneva County in 1936. She grew up with her parents and twelve siblings, all working on a farm. In 1955 she moved to Tuscaloosa and began attending First African Baptist church. She finished her undergraduate studies at Stillman College and later attained her Master’s Degree from the University of Alabama. She taught school for thirty-seven years at Holt Elementary School and then another three years in the kindergarten of First African Baptist. Her first year of teaching at Holt was the first year of integration in the Tuscaloosa County Schools. Ms. Lawson is heavily involved in First African Baptist and was present for the event known as Bloody Tuesday. She was delivering food to the rally, arriving after the police had begun to use force to quell the marchers’ enthusiasm. She remembers seeing policemen inside the church building hitting several marchers while other officials outside shot tear gas and firehoses at the church building, breaking the windows of the church. In this interview, Ms. Lawson also discusses how real estate planning was used to segregate neighborhoods of Tuscaloosa. 2 HILARY: Alright, so, Ms. Betty Lawson, where were you born? MS. LAWSON: I was born in Hartford Alabama, and that’s in Geneva County. HILARY: Okay, and when was that? MS. LAWSON: That was in March [of] ‘36. HILARY: Okay and you grew up there? MS. LAWSON: Yes. HILARY: Do you have any siblings? MS. -

Interpreting Racial Politics

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage Benjamin Rex LaPoe II Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation LaPoe II, Benjamin Rex, "Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 45. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/45 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. INTERPRETING RACIAL POLITICS: BLACK AND MAINSTREAM PRESS WEB SITE TEA PARTY COVERAGE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Benjamin Rex LaPoe II B.A. West Virginia University, 2003 M.S. West Virginia University, 2008 August 2013 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction