Credible Comparisons Using Interpersonally Incomparable Data: Nonparametric Scales with Anchoring Vignettes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob James Three Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob James Three mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: Three Country: US Released: 1976 Style: Fusion MP3 version RAR size: 1301 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1416 mb WMA version RAR size: 1546 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 503 Other Formats: VQF MMF MP2 AA WAV AU ADX Tracklist Hide Credits One Mint Julep 1 9:09 Composed By – R. Toombs* Women Of Ireland 2 8:06 Composed By – S. Ó Riada* Westchester Lady 3 7:27 Composed By – B. James* Storm King 4 6:36 Composed By – B. James* Jamaica Farewell 5 5:26 Composed By – L. Burgess* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tappen Zee Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Tappen Zee Records, Inc. Licensed From – Castle Communications PLC Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Remastered At – CBS Studios, New York Credits Bass – Gary King (tracks: 1, 2, 5), Will Lee (tracks: 3, 4) Bass Trombone – Dave Taylor* Bass Trombone, Tuba – Dave Bargeron Cello – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken Drums – Andy Newmark (tracks: 1), Harvey Mason (tracks: 2 to 5) Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Flute – Hubert Laws, Jerry Dodgion Flute, Tenor Saxophone – Eddie Daniels Guitar – Eric Gale (tracks: 2 to 4), Hugh McCracken (tracks: 2 to 4), Jeff Mironov (tracks: 1) Harp – Gloria Agostini Keyboards – Bob James Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Photography By [Cover] – Richard Alcorn Producer – Creed Taylor Remastered By – Stew Romain* Supervised By [Re-mastering] – Joe Jorgensen Tenor Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone, Tin Whistle – Grover Washington, Jr. Trombone – Wayne Andre Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Lew Soloff, Marvin Stamm Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Frederick Buldrini, Harold Kohon, Harry Cykman, Lewis Eley, Matthew Raimondi, Max Ellen Notes Originally released in 1976. -

ABQ Free Press, October 22, 2014

VOL I, Issue 14, October 22, 2014 Still FREE After All These Months DOJ Made Us Buy AR-15s, APD Says PAGE 5 Joe Monahan: Why Negative TV Ads Work Judge Candidate PAGE 6 Is Traffic Ticket Magnet PAGE 9 Will New Police Board Be Toothless? PAGE 10 VALERIE PLAME SPEAKS OUT ON SUSANA, GARY PAGE 7 PAGE 2 • October 22, 2014 • ABQ FREE PRESS NEWS www.freeabq.com www.abqarts.com ABQ Free Press Pulp News Editor: [email protected] COMPILED BY ABQ FREE PRESS STAFF VOL I, Issue 14, October 22, 2014 Still FREE After All These Months Associate Editor, News: Dennis Domrzalski Ebola’s threat psychotic killers. The latest example is (505) 306-3260 “Twisty the Clown,” a killer clown on Associate Editor, Arts: Outside of West Africa, the United the FX show “American Horror Story.” [email protected] States, France and the United Kingdom “We do not support in any way, shape Advertising: are most at risk for the spread of the or form any medium that sensational- [email protected] IN THIS ISSUE Ebola virus, but they also are best izes or adds to coulrophobia, or clown [email protected] equipped to contain it. China and India fear,” the group’s president, Glenn [email protected] are less likely to see infected persons Kohlberger, told the Hollywood On Twitter: @freeabq because of lack of travel connections Reporter. Kohlberger’s 2,500-member to West Africa, but if they do, their organization may be fighting a losing NEWS huge populations and poor health battle. In the 1970s, Chicago mass Editor systems could leave them open to ABQ Free Press Pulp News .............................................................................................................Page 2 murderer John Wayne Gacy, who Dan Vukelich mass infection. -

Publication, Publication

Publication, Publication Gary King, Harvard University Introduction The broader scientific community Some students ask: “Why begin an both collectively and in many other in- original research paper by replicating I show herein how to write a publish- dividual fields is also moving strongly some old work?” A paper that is publish- able paper by beginning with the replica- in the direction of participating in or able is one that by definition advances tion of a published article. This strategy requiring some form of data sharing. knowledge. If you start by replicating an seems to work well for class projects in Recipients of grants from the National existing work, then you are right at the producing papers that ultimately get pub- Science Foundation and the National cutting edge of the field. If you can then lished, helping to professionalize students Institutes of Health now are required to improve any one aspect of the research into the discipline, and teaching the sci- make data available to other scholars that makes a substantive difference and entific norms of the free exchange of upon publication or within a year of the is defensible, you have a publishable academic information. I begin by briefly termination of their grant. Replicating, paper. If instead you begin a project revisiting the prominent debate on repli- and thus collectively and publicly vali- from scratch without replication, you cation our discipline had a decade ago dating, the integrity of our published need to defend every coding decision, and some of the progress made in data work is often still more difficult than it every hypothesis, every data source, sharing since. -

Ordinary Economic Voting Behavior in the Extraordinary Election of Adolf Hitler

THE JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC HISTORY VOLUME 68 DECEMBER 2008 NUMBER 4 Ordinary Economic Voting Behavior in the Extraordinary Election of Adolf Hitler GARY KING, ORI ROSEN, MARTIN TANNER, AND ALEXANDER F. WAGNER The enormous Nazi voting literature rarely builds on modern statistical or economic research. By adding these approaches, we find that the most widely accepted existing theories of this era cannot distinguish the Weimar elections from almost any others in any country. Via a retrospective voting account, we show that voters most hurt by the depression, and most likely to oppose the government, fall into separate groups with divergent interests. This explains why some turned to the Nazis and others turned away. The consequences of Hitler’s election were extraordinary, but the voting behavior that led to it was not. ow did free and fair democratic elections lead to the extraordinary H antidemocratic Nazi Party winning control of the Weimar Republic? The profound implications of this question have led “Who voted for Hitler?” to be the most studied question in the history of voting behavior research. Indeed, understanding who voted for Hitler is The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 68, No. 4 (December 2008). © The Economic History Association. All rights reserved. ISSN 0022-0507. Gary King is David Florence Professor of Government, Department of Government, Harvard University, Institute for Quantitative Social Science, 1737 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. E-mail: [email protected]. Ori Rosen is Associate Professor, Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, Bell Hall 221, El Paso, TX 79968. E-mail: [email protected]. -

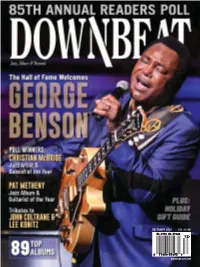

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Londonjazz: LP Review: George Benson – Body Talk 01.12.14 09:32

LondonJazz: LP Review: George Benson – Body Talk 01.12.14 09:32 Diese Website verwendet Cookies, um die Bereitstellung von Diensten zu verbessern. Durch die Nutzung dieser Website erklären Sie sich mit der Verwendung von Cookies einverstanden. Home Venues Can We Help? Team LondonJazz - Facebook THE WEEKLY NEWSLETTER LP Review: George Benson – To subscribe for our weekly newsletter, Just email the Editor (in 'Team' Body Talk above) Tweets Follow LondonJazz 1h News BIMHUIS 40! @LondonJazz NEWS: Three out-of- London gigs for NEON Quartet nblo.gs/11IW3m Expand Sinclair Jazz 15h Photos @SinclairJazz New Twitter for Dec 14 onwards for David Sinclair jazzphotographs.com 25 year archive of high quality jazz photos @ddbprods plz RT Retweeted by LondonJazz News Expand STONEY LANE RECORDS George Benson – Body Talk Mike Collins 15h @jazzyblogman (Speakers Corner/CTI 6033. LP review by Andrew Cartmel) My CD REVIEW for @LondonJazz : Euan Following on the furry heels of White Rabbit and recorded in 1973, Body Talk was Burton - Too Much Love George Benson’s sixth CTI album (counting the A&M issues), and by now the nblo.gs/11IwUP guitarist’s recordings for Creed Taylor had settled into a smooth and relatively Retweeted by lucrative groove — although nothing like the enormous commercial success that LondonJazz News was to come with Benson’s move to Warner Bros, his subsequent album Breezin’ Expand and his vocal rendition of This Masquerade (a top ten hit and a Grammy winner) — Breezin’ was the first jazz album to go platinum. Tweet to @LondonJazz But it’s Benson’s sequence of albums for Creed Taylor Incorporated which arguably (Birmingham) represent the cream of his work, and are indisputably the purest in terms of jazz. -

The Foreign Service Journal, May 1954

‘No, Giovanni. Io dico, ‘Make “ 1 he only whisky bottled under Mine 909"! Ca-na-da Schenley supervision of the Governo 909.'’ Canadese at exactly 90.9 *■ “Ah, si—whisky del Canada!” proof, the one proof of perfec¬ “No, not just any Canadian tion. Nove — zero — nove — whisky. Bring me the one with 909—eapisci?” the naturally fine taste . the Aove—zero—novel Natural one that fills your glass with the mente . il migliore*!” beauty and magic of Canada.” “Non capisco.” '(Translation: 909... naturally... the finest!) (Haichcnlej 7/7777777/777/7/ SCHEME* lTP ©1954 Canadian Schenley, Ltd. AGED AND BOTTLED DNDER SUPERVISION OF THE CANADIAN GOVERNMENT* CANADIAN SCHENLEY, LT SERVING YOUR BUSINESS AND PLEASURE IS OUR PLEASURE AND BUSINESS- AMERICAN EXPRESS WORLD SERVICE Here are the world-wide, world-wise services offered^ by American Express . 243 offices in 35 nations i always ready to serve you, completely, expertly, j whatever your needs for business or pleasure. .] MONEY ORDERS TRAVELERS CHEQUES Pay bills and transmit funds Smart travelers insist on with convenient, econom¬ American Express Travelers ical American Express Cheques. They’re 100% safe Money Orders... available ... the most widely accepted throughout the U. S. at Cheques in the world ... on neighborhood stores, Rail¬ sale at Banks, Railway Ex¬ way Express and Western press and Western Union Union offices. offices. OTHER FINANCIAL SERVICES TRAVEL SERVICES Swift . convenient and The trained and experi¬ dependable, other world¬ enced staff of American wide American Express Express will provide air or financial services include: steamship tickets . hotel foreign remittances, mail and reservations . uniformed cable transfer of funds, and interpreters . -

Bob James Three Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob James Three mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: Three Country: Japan Released: 1979 Style: Fusion MP3 version RAR size: 1638 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1116 mb WMA version RAR size: 1430 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 930 Other Formats: XM AAC VOC VQF DTS DMF WAV Tracklist Hide Credits One Mint Julep A1 9:04 Drums – Andy NewmarkGuitar – Jeff Mironov A2 Women Of Ireland 8:00 Westchester Lady B1 7:23 Bass – Will Lee Storm King B2 6:33 Bass – Will Lee B3 Jamaica Farewell 5:21 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Credits Bass – Gary King (tracks: A1, A2, B3) Bass Trombone – Dave Taylor* Bass Trombone, Tuba – Dave Bargeron Cello – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken Design [Album] – Rene Schumacher Drums – Harvey Mason (tracks: A2 to B3) Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Flute – Hubert Laws, Jerry Dodgion Flute, Tenor Saxophone – Eddie Daniels Guitar – Eric Gale (tracks: A2 to B2), Hugh McCracken (tracks: A2 to B2) Harp – Gloria Agostini Keyboards – Bob James Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Photography By – Richard Alcorn Producer – Creed Taylor Tenor Saxophone, Tin Whistle – Grover Washington, Jr. Trombone – Wayne Andre Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Lew Soloff, Marvin Stamm Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Frederick Buldrini, Harold Kohon, Harry Cykman, Lewis Eley, Matthew Raimondi, Max Ellen Notes Pressing variation with "Side 1 and 2" in upper left of labels. Bottom edge text includes "Unauthorized duplication is a violation of applicable laws". LP housed in company "CTI" sleeve. Recorded at Van Gelder Studios. ℗ 1976, Creed Taylor, Inc. -

The World's End

by Simon Pegg & Edgar Wright GARY (V.O.) Ever had one of those nights that starts like any other night but ends up being the best night of your life? I did. INT./EXT. 1990 - DAY/NIGHT Over corridors, school children and falling A4 paper. The images match the narration, warm with nostalgia. GARY (V.O.) It was June 22nd 1990, our final day of school. There were five of us. Oliver Chamberlain, Peter Page, Steven Prince, Andy Knightley and me. They called me The King. Because my name's Gary King. We see a teenage GARY, the school cool cat with trendy hair, black trench coat and irrepressible grin. GARY (V.O.) Me and the boys, we were inseparable: Ollie was funny, he fancied himself as a bit of a player but really, he was all mouth. We called him O-Man because he had a birthmark that looked like a six. He loved it. We see a teenage OLIVER, a yuppie in training, with city boy accessories and a brick of a mobile phone. The boys try to distract him. He gives them the finger, mouths "Fuck off". GARY (V.O.) Pete was the baby of the group. We sort of took him under our wing. Pete wasn't the kind of kid we'd usually hang out with but he was good for a laugh and his dad was minted. Diminutive PETER gets nudged in the corridor by a BURLY KID. In Peter's garden, Gary cannonballs into a swimming pool, soaking an older man who is apparently Peter's dad. -

A Comment on the King Ecological Inference Solution

I the Assumption Fits ::: : A Comment on the King Ecological Inference Solution Wendy K. Tam Cho Abstract I examine a recently prop osed solution to the ecological inference prob- lem King 1997. It is asserted that the prop osed mo del is able to recon- struct individual-level b ehavior from aggregate data. I discuss in detail b oth the b ene ts and limitations of this mo del. The assumptions of the basic mo del are often inappropriate for instances of aggregate data. The extended version of the mo del is able to correct for some of these limitations. However, it is dicult in most cases to apply the extended mo del prop erly. Intro duction For a wide variety of questions, esp ecially those which involve histori- cal researchor volatile issues such as race, aggregate data supply one of the only sources of reliable data. However, making inferences ab out micro-level units when the only available data are aggregated ab ove the micro-level unit in question is extremely dicult. Consider the example of aggregate data analysis in investigating the gender gap by estimat- ing presidential voting b ehavior among women. For each precinct, the Thanks to Bruce Cain, Douglas Rivers, Gary King, Walter Mebane, Henry Brady, Chris Achen, David Freedman, Brian Gaines, Jasjeet Sekhon, Simon Jack- man, Michael Herron, Rui de Figueiredo, JakeBowers, Cara Wong, Mike Alvarez, and Jonathan Nagler for helpful comments. I am also grateful to participants at a CIC Video Metho ds Seminar and at the University of California, Berkeley, for lively and helpful discussions, and to the National Science Foundation Grant No. -

Hank Crawford I Hear a Symphony Mp3, Flac, Wma

Hank Crawford I Hear A Symphony mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: I Hear A Symphony Country: Japan Released: 1975 Style: Soul-Jazz, Jazz-Funk, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1618 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1635 mb WMA version RAR size: 1484 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 110 Other Formats: RA APE MP4 MP3 TTA DMF AHX Tracklist A1 I Hear A Symphony 4:45 A2 Madison (Spirit, The Power) 3:55 A3 Hang It On The Ceiling 4:15 A4 The Stripper 4:00 B1 Sugar Free 4:40 B2 Love Won't Let Me Wait 4:00 B3 I'll Move You No Mountain 4:05 B4 Baby This Love I Have 3:35 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Produced For – CTI Records Manufactured By – King Record Co. Ltd Credits Alto Saxophone – Hank Crawford Arranged By, Conductor – David Matthews* Bass – Gary King Bass Trombone – Dave Taylor*, Paul Faulise, Tony Studd Cello – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken, Seymour Barab Drums – Steve Gadd Electric Piano – Leon Pendarvis Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Guitar – Eric Gale Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Producer – Creed Taylor Shaker, Tambourine – Idris Muhammad Trombone – Barry Rogers, Fred Wesley Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Alan Rubin, John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Robert Millikan Violin – Charles Libove, David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Harold Kohon, Harry Cykman, Joe Malin, Joe Pintavalle*, Lewis Eley, Max Ellen, Max Pollikoff, Paul Gershman, Raoul Poliakin, Richard Sortomme Vocals – Patti Austin Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year KU-26 S1 Hank Crawford I Hear A Symphony (LP, Album) Kudu KU-26 S1 US 1975 I Hear A Symphony (CD, Album, RE, KICJ 8364 Hank Crawford Kudu KICJ 8364 Japan 2001 RM) I Hear A Symphony (CD, Album, RE, KICJ 2218 Hank Crawford Kudu KICJ 2218 Japan 2007 RM) KU-26-S1 Hank Crawford I Hear A Symphony (LP, Album) Kudu KU-26-S1 US 1975 KU 26 Hank Crawford I Hear A Symphony (LP, Album) Kudu KU 26 UK 1976 Related Music albums to I Hear A Symphony by Hank Crawford Deodato - 2001 Ron Carter - Pick 'Em J & K - Stonebone Grover Washington Jr. -

Weeks 1 and 2: Models for Panel and Time-Series Cross-Section Data

Advanced Topics in Maximum Likelihood Estimation 2015 Weeks 1 and 2: Models for Panel and Time-Series Cross-Section Data Summer 2015 Professor David Darmofal [email protected], [email protected] University of South Carolina Weeks 1-2 (July 20th-July 31st) Course Description These two weeks of the advanced MLE course will focus on methods and models for panel and time-series cross-sectional (TSCS) data. These types of data occur when we have observations for multiple units collected at multiple points in time. Panel data typically are sample data in which there is a large number of cross-sectional units and few time points. TSCS data are typically data in which the units are of interest in themselves, the number of time points is much larger than in panel data, and the number of time points is either larger or approximately equal to the number of cross-sectional units. Since TSCS data are more widely used in political science outside of the area of panel survey studies, much of these weeks will focus on TSCS data rather than panel data. This portion of the class will cover several questions that are central to the use of TSCS and panel data. Among these are fixed effects and random effects models, dynamic models, random coefficient models, models for limited dependent variables, models for spatial dependence, and panel attrition. Students will be asked to complete problem sets that involve estimating models for data collected in time and space. Because the focus of this class is on providing students with knowledge of methods they can apply in their own research, students will also be asked to write a short research proposal that describes a research question and hypotheses that can be tested using the methods learned in this course.