Mark Twain in the Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

SAV THE BEST IN COMICS & E LEGO ® PUBLICATIONS! W 15 HEN % 1994 --2013 Y ORD OU ON ER LINE FALL 2013 ! AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: The 1950 s BILL SCHELLY tackles comics of the Atomic Era of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley: EC’s TALES OF THE CRYPT, MAD, CARL BARKS ’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, re-tooling the FLASH in Showcase #4, return of Timely’s CAPTAIN AMERICA, HUMAN TORCH and SUB-MARINER , FREDRIC WERTHAM ’s anti-comics campaign, and more! Ships August 2013 Ambitious new series of FULL- (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 COLOR HARDCOVERS (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490540 documenting each 1965-69 decade of comic JOHN WELLS covers the transformation of MARVEL book history! COMICS into a pop phenomenon, Wally Wood’s TOWER COMICS , CHARLTON ’s Action Heroes, the BATMAN TV SHOW , Roy Thomas, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil lead - ing a youth wave in comics, GOLD KEY digests, the Archies and Josie & the Pussycats, and more! Ships March 2014 (224-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $39.95 (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 9781605490557 The 1970s ALSO AVAILABLE NOW: JASON SACKS & KEITH DALLAS detail the emerging Bronze Age of comics: Relevance with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’s GREEN 1960-64: (224-pages) $39.95 • (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-045-8 LANTERN , Jack Kirby’s FOURTH WORLD saga, Comics Code revisions that opens the floodgates for monsters and the supernatural, 1980s: (288-pages) $41.95 • (Digital Edition) $13.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-046-5 Jenette Kahn’s arrival at DC and the subsequent DC IMPLOSION , the coming of Jim Shooter and the DIRECT MARKET , and more! COMING SOON: 1940-44, 1945-49 and 1990s (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 • (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490564 • Ships July 2014 Our newest mag: Comic Book Creator! ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. -

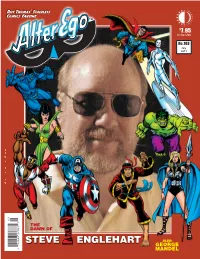

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: a Survey and Analysis

The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: A Survey and Analysis STEPHEN E. TABACHNICK University of Memphis OWING TO A LARGE NUMBER of excellent adaptations, it is now possible to read and to teach a good deal ot the Transition period litera- ture with the aid of graphic, or comic book, novels. The graphic novei is an extended comic book, written by adults for adults, which treats important content in a serious artistic way and makes use of high- quality paper and production techniques not available to the creators of the Sunday comics and traditional comic books. This flourishing new genre can be traced to Belgian artist Frans Masereel's wordless wood- cut novel. Passionate Journey (1919), but the form really took off in the 1960s and 1970s when creators in a number of countries began to employ both words and pictures. Despite the fictional implication of graphic "novel," the genre does not limit itself to fiction and includes numerous works of autobiography, biography, travel, history, reportage and even poetry, including a brilliant parody of T. S. Eliot's Waste Land by Martin Rowson (New York: Harper and Row, 1990) which perfectly captures the spirit of the original. However, most of the adaptations of 1880-1920 British literature that have been published to date (and of which I am aware) have been limited to fiction, and because of space considerations, only some of them can be examined bere. In addition to works now in print, I will include a few out-of-print graphic novel adap- tations of 1880-1920 literature hecause they are particularly interest- ing and hopefully may return to print one day, since graphic novels, like traditional comics, go in and out of print with alarming frequency. -

RACHAEL SMITH, BENJAMIN DICKSON Queen's Favorite Witch #1

PAPERCUTZ • OCTOBER 2021 JUVENILE FICTION / COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS / FANTASY RACHAEL SMITH, BENJAMIN DICKSON Queen's Favorite Witch #1 Meet Daisy, a precocious, down on her luck witch who is thrust into the world of royal intrigue when she applies to become The Queen's Favorite Witch! Elizabethan England is a time of superstition and strange goings on. If you have a problem, it’s common to go to a witch for help. And Queen Elizabeth I is no different… When Daisy -- a precocious young witch -- learns of the death of the Queen's Royal Witch, she flies to London to audition as her replacement. But Daisy is from a poor family, and they don't let just anyone into the Royal Court. The only OCTOBER Papercutz way into the palace is to take a job as a cleaner. Juvenile Fiction / Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy As Daisy cleans the palace, she draws the attention of On Sale 10/19/2021 Elizabeth's doctor (and arch-heretic) John Dee, who places Ages 7 to 12 her into the auditions -- much to the chagrin of her more Trade Paperback , 112 pages well-to-do competitors. But Dee knows how dangerous the 9 in H | 6 in W Carton Quantity: 60 corridors of power have become, with dark forces ISBN: 9781545807224 manipulating events for their own ends. To him, Daisy $9.99 / $12.99 Can. represents a wild card -- ... Benjamin Dickson is a writer, artist and lecturer who most recently produced the critically-acclaimed A New Jerusalem for New Internationalist/Myriad Editions (also published in France as Le Retour, by Actes Sud). -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

List of Publishers' Representatives

DISTRICT SUPPLEMENTAL INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS (9-12) CURRICULAR AREA Agricultural and Environmental Education COURSE Environmental Education Grade(s): 9-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Naturegraph Publishers Californian Wildlife Region, 3rd Revised and Brown0879612010 1999 1976 Expanded Ed. University of California Press Introduction to California Plant Life Ornduff, et al.0520237048 2003 1976 COURSE Floral Occupations Grade(s): 10-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Ortho Books All About Houseplants Ortho Books0897214277 1999 1976 COURSE Floriculture Grade(s): 7-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Ortho Books All About Houseplants Ortho Books0897214277 1999 1976 COURSE Forestry Grade(s): 9-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Naturegraph Publishers Californian Wildlife Region, 3rd Revised and Brown0879612010 1999 1976 Expanded Ed. University of California Press Introduction to California Plant Life Ornduff, et al.0520237048 2003 1976 University of California Press Native Shrubs of Southern California Raven0520010507 1966 1976 COURSE Horticulture Grade(s): 6-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Ortho Books All About Bulbs Ortho Books0897214250 1999 1986 Ortho Books All About Masonry Basics Ortho Books0897214382 2000 1986 Ortho Books All About Pruning Ortho Books0897214293 1999 1986 Ortho Books All About Roses Ortho Books0897214285 1999 1986 Wednesday, February 28, 2007 Page 1 of 343 Ortho Books All About Vegetables Ortho Books0897214196 1999 1978 Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 5th Ed., Ingels0827367368 1997 1978 Instructor's Guide Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 5th Ed., Ingels082736539X 1997 1999 Residential Design Workbook Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 5th Ed., Ingels0827365403 1997 1999 Residential Design Workbook, Instructor's Guide Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 6th Ed. -

Graphic Horror Teacher Tips & Activities

Graphic Horror Teacher Tips & Activities Illustration from Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde Based on the series Graphic Classics published by Magic Wagon, a division of ABDO. 1-800-800-1312 • www.abdopublishing.com Not for resale • Photocopy and adapt as needed for classroom and library use. Table Of Contents Comic book text is short, but that doesn’t mean students don’t learn a lot from it! Comic books and graphic novels can be used to teach reading processes and writing techniques, such as pacing, as well as expand vocabulary. Use this PDF to help students get more out of their comic book reading. Here are some of the projects you can give to your students to make comics educational and enjoyable! General Activities Publication History & Research --------------------------------- 1 Book vs. Movie vs. Graphic Novel ----------------------------- 2 Shared Reading & Fluency Practice --------------------------- 3 Scary Horror Stories ------------------------------------------------ 4 Create a Ghost Story ---------------------------------------------- 4 Work with Your Library -------------------------------------------- 5 Activities For Each Story The Creature from the Depths ---------------------------------- 6 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde -------------------------------------------- 7 Frankenstein ----------------------------------------------------------- 8 The Legend of Sleepy Hollow ----------------------------------- 9 Mummy ------------------------------------------------------------------ 10 Werewolf ---------------------------------------------------------------- -

BERNARD BAILY Vol

Roy Thomas’ Star-Bedecked $ Comics Fanzine JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT 8.95 YOU KNEW EVERYTHING THERE In the USA WAS TO KNOW ABOUT THE No.109 May JUSTICE 2012 SOCIETY ofAMERICA!™ 5 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 Art © DC Comics; Justice Society of America TM & © 2012 DC Comics. Plus: SPECTRE & HOUR-MAN 6 2 8 Co-Creator 1 BERNARD BAILY Vol. 3, No. 109 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck AT LAST! Comic Crypt Editor ALL IN Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll COLOR FOR $8.95! Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artist Contents George Pérez Writer/Editorial: An All-Star Cast—Of Mind. 2 Cover Colorist Bernard Baily: The Early Years . 3 Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Ken Quattro examines the career of the artist who co-created The Spectre and Hour-Man. “Fairytales Can Come True…” . 17 Rob Allen Roger Hill The Roy Thomas/Michael Bair 1980s JSA retro-series that didn’t quite happen! Heidi Amash Allan Holtz Dave Armstrong Carmine Infantino What If All-Star Comics Had Sported A Variant Line-up? . 25 Amy Baily William B. Jones, Jr. Eugene Baily Jim Kealy Hurricane Heeran imagines different 1940s JSA memberships—and rivals! Jill Baily Kirk Kimball “Will” Power. 33 Regina Baily Paul Levitz Stephen Baily Mark Lewis Pages from that legendary “lost” Golden Age JSA epic—in color for the first time ever! Michael Bair Bob Lubbers “I Absolutely Love What I’m Doing!” . -

Creative Learning in Afterschool Comic Book Clubs

The Robert Bowne Afterschool Matters Foundation OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES The Art of Democracy/ Democracy as Art: Creative Learning in Afterschool Comic Book Clubs MICHAEL BITZ Civic Connections: Urban Debate and Democracy in Action during Out-of-School Time GEORGIA HALL #7 FALL 2006 The Robert Bowne Foundation Board of Trustees Edmund A. Stanley, Jr., Founder Jennifer Stanley, Chair & President Suzanne C. Carothers, Ph.D., First Vice-President Susan W. Cummiskey, Secretary-Treasurer Dianne Kangisser Jane Quinn Ernest Tollerson Franz von Ziegesar Afterschool Matters Editorial Review Board Charline Barnes Andrews University Mollie Blackburn Ohio State University An-Me Chung C.S. Mott Foundation Pat Edwards Consultant Meredith Honig University of Maryland Anne Lawrence The Robert Bowne Foundation Debe Loxton LA’s BEST Greg McCaslin Center for Arts Education Jeanne Mullgrav New York City Department of Youth & Community Development Gil Noam Program in Afterschool Education and Research, Harvard University Joseph Polman University of Missouri–St. Louis Carter Savage Boys & Girls Clubs of America Katherine Schultz University of Pennsylvania Jason Schwartzman Christian Children’s Fund Joyce Shortt National Institute on Out of School Time (NIOST) Many thanks to Bowne & Company for printing this publication free of charge. RobertThe Bowne Foundation STAFF Lena O. Townsend Executive Director Anne H. Lawrence Program Officer Sara Hill, Ed.D. Research Officer Afterschool Matters Occasional Paper Series No. 7, Fall 2006 Sara Hill, Ed.D. Project Manager -

Libro Gratis Dracula, 2 (Graphic Classics)

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Dracula, 2 (Graphic Classics) PDF DRACULA, 2 (GRAPHIC CLASSICS) Tapa blanda Abreviado, 2 junio 2020 Author : Descripcin del productoBiografa del autorAbraham 'Bram' Stoker (1847 - 1912) was educated at Trinity College, Dublin and joined the Irish Civil Service before his love of theatre led him to become the unpaid drama critic for the Dublin Mail. He went on to act as as manager and secretary for the actor Sir Henry Irving, while writing his novels, the most famous of which is Dracula. Abraham (Bram) Stoker was an Irish writer, best known for his Gothic classic Dracula, which continues to influence horror writers and fans more than 100 years after it was first published.Educated at Trinity College, Dublin, in science, mathematics, oratory, history, and composition, Stoker's writing was greatly influenced by his father's interest in theatre and his mother's gruesome stories ... I collect graphic novels based on classic literature, so I had high hopes for this series by Barron's. In addition to Dracula, they've also published Treasure Island, Frankenstein, Kidnapped, Moby-Dick, and Journey to the Center of the Earth (maybe others I'm unaware of too). 'Dracula (Dover Graphic Novel Classics)' is a faithful adaptation of the novel told in graphic novel format. As a bonus, all the art is presented black and white so that it can be colored. It's all here. The creepy castle and creepier Count Dracula. The Harkners, Van Helsing and Renfield. The dark and tragic death. This item: Dracula Graphic Novel (Illustrated Classics) by Bram Stoker Paperback $9.95. -

From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― the Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated

Submitted October 3, 2011 Published January 27, 2012 Proposé le 3 octobre 2011 Publié le 27 janvier 2012 From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― The Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated William B. Jones, Jr. Abstract From 1941 to 1971, the Classics Illustrated series of comic-book adaptations of works by Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, and others provided a gateway to great literature for millions of young readers. Jules Verne was the most popular author in the Classics catalog, with ten titles in circulation. The first of these to be adapted, Michael Strogoff (June 1946), was the favorite of the Russian-born series founder, Albert L. Kanter. The last to be included, Tigers and Traitors (May 1962), indicated how far among the Extraordinary Voyages the editorial selections could range. This article explores the Classics Illustrated pictorial abridgments of such well-known novels as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in 80 Days and more esoteric selections such as Off on a Comet and Robur the Conqueror. Attention is given to both the adaptations and the artwork, generously represented, that first drew many readers to Jules Verne. Click on images to view in full size. Résumé De 1941 à 1971, la collection de bandes dessinées des Classics Illustrated (Classiques illustrés) offrant des adaptations d'œuvres de Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, et d'autres a fourni une passerelle vers la grande littérature pour des millions de jeunes lecteurs. Jules Verne a été l'auteur le plus populaire du catalogue des Classics, avec dix titres en circulation.