The Flattening of “Collage”*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

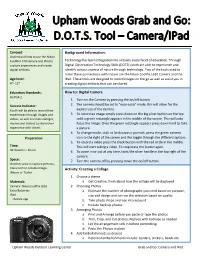

Grab and Go Camera and Ipad

Concept: Background Information: Understand how to use the Nikon CoolPix L610 camera and IPad to Technology has been integrated into virtually every facet of education. Through capture experiences and create Digital Observation Technology Skills (DOTS) youth are able to experience and digital artifacts. identify various aspects of nature through technology. Two of the tools used to make these connections with nature are the Nikon CoolPix L610 Camera and the Age level: IPad. These tools are designed to record images on the go as well as assist you in 4th- 12th creating digital artifacts that can be shared. Education Standards: How to: Digital Camera HS-PS4-2 1. Turn on the Camera by pressing the on/off button. Success Indicator: 2. The camera should be set to “easy-auto” mode, this will allow for the Youth will be able to record their easiest use of the camera. experiences through images and 3. To record an image simply press down on the big silver button on the top videos, as well as create collages, until a green rectangle appears in the middle of the screen. This will auto movies and trailers to share their focus the image. Once the green rectangle appears press down hard to take experience with others. a picture. 4. To change mode, such as landscape or portrait, press the green camera Preparation icon to the right of the screen and the toggle through the different options. 5. To record a video press the black button with the red circle in the middle. Time: This will start taking a video. -

With Dada and Pop Art Influence

With Dada and Pop Art Influence The non-art movement • 1916-1923 • Reaction to the horror of World War I • Artists were mostly French and German. They took refuge in neutral Switzerland. • They were angry at the European society that had allowed the war to happen. • Dada was a form of protest. • It’s intention was to provoke and shock The name “Dada” was chosen because it was nonsensical. They wanted a name that made the least amount of sense. • They used any public forum to spit on: nationalism rationalism materialism and society in general Mona Lisa with a Mustache “The Fountain” “The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even” George Groz “Remember Uncle Augustus the Unhappy Inventor”(collage) Raoul Hausmann “ABCD” (collage) Merit Oppenheim “Luncheon in Fur” Using pre-existing objects or images with little or no transformation applied to them Artist use borrowed elements in their creation of a new work • Dada self-destructed when it was in danger of becoming “acceptable.” • The Dada movement and the Surrealists have influenced many important artists. Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) became one of the most famous artists to use assemblage. His work is both surreal and poetic. A 3-D form of using "found" objects arranged in such a way that they create a piece of art. The Pop American artist, Robert Rauschenberg, uses assemblage, painting, printmaking and collage in his work. He is directly influenced by the Dada-ists. “Canyon” “Monogram” “Bed” “Coca-cola Plan” “Retroactive” • These artist use borrowed elements in their creation to make a new work of art! • As long as those portions of copyrighted works are used to create a completely new and different work of art it was OK. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: the Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: The Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs Ann Lane Hedlund University of Arizona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Hedlund, Ann Lane, "Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: The Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 462. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/462 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tapestry Translations in the Twentieth Century: The Entwined Roles of Artists, Weavers, and Editeurs Ann Lane Hedlund The Gloria F. Ross Center for Tapestry Studies Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona, Tucson [email protected] Historically, European tapestry making involved collaboration among artists, designers, draftsmen, cartoon makers, spinners, dyers, weavers, patrons, dealers, and other professionals. This specialized system of labor continued in modified form into the twentieth century in certain European and American weaving workshops. In contrast and with a small number of exceptions, American tapestry in the last half of the twentieth century has centered on weaver-artists working individually in their studios from their own designs. This paper focuses, in a very preliminary way, on one exceptional example of continuity, or revival, of the European specialized labor system—the creation of a group of twentieth century tapestries orchestrated by editeur Gloria F. -

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 17 (January 2017), No. 11 Jared Goss, French art deco. New York and New Haven, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Distributed by Yale University Press, 2014, ix, 270 p. $50.00 U.S. (cl). ISBN 9781588395252 (Metropolitan Museum of Art), 9780300204308 (Yale University Press). Review by Tim Benton, Open University, London. The Met was an early purchaser of French art déco (short for arts décoratifs), beginning even before the American deputation visited the Exposition des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris (1925). As Jared Goss explains, a generous gift by Edward C. Moore Junior enabled the Museum to continue purchasing Art Deco work into the 1960s. So the exhibition “Masterpieces of French Art Deco” was a welcome endeavour to put the collection on show. Many of the items were purchased or donated between 1922 and 1929, at which time the fashion for expensive French decorative arts was hit hard by the Wall Street crash. The subsequent history of Art Deco underwent a transformation in which the French déco metamorphosed into a global phenomenon which reached from Rio de Janeiro to Bombay, touching even England, bastion of the Arts and Crafts and fiercely resistant to Art Nouveau. Thus déco and Deco are really quite different things: the first defined by its very high standards of craftsmanship and luxurious materials, the second opening itself to industrial production and the 1930s style known as Streamlining—a particularly American phenomenon (despite its European roots)—which morphed gradually into the high extravaganzas of industrial design of the 1950s. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Art Matters Lesson Plan Art Play Lesson #3: Pattern & Colored

Art Matters Lesson Plan Art Play Lesson #3: Pattern & Colored Paper Collage Shelly Korte & Vashti B Moss 4/14/2020 Tools Materials scissors (optional) Colored paper (tissue paper, magazine Table cover (optional) pages, and/ or construction paper) Heavy cardboard glue stick plain white paper (cardstock, mixed media paper, or printer paper) Wet wipes Inspired by: Ramona Sakiestewa, contemporary New Mexican Hopi American tapestry and paper artist. Facets/4, dyed and woven wool. 50in x 90in, currently in the Common Ground collection in Albuquerque Museum. https://ramonasakiestewa.com/artwork/ Set Up 1. Cover work area with tarp or spare paper sheets 2. Each artist will have 2-3 sheets of white paper, a selection of colored paper, and a glue stick Instructions Part 1: Relax and Share a. As a group, take a deep breath through your nose and exhale or sigh out of your mouth. Do this two more times as a group. As you relax your shoulders, your face, and your mind, come into the present moment. b. Check in with how you’re feeling and give it a shape and color. If you’re in a group, go around and give everyone a chance to say this out loud. Part 2: Warm-up/Illustrating Words with Shape and Pattern a. Take a deep breath. Relax your shoulders, your arms, your hands. Remember to pause and do this periodically as you work. b. Students artists will tear (or cut) paper into shapes. Considering color, the grain/tearability of the paper. Notice how it feels to tear the paper. Notice how it feels to change tear direction and method. -

Ovidiu Solcan Collage Artist RO&US.Cdr

OVIDIU SOLCAN | COLLAGE ARTIST OVIDIU SOLCAN COLLAGE ARTIST Ovidiu Solcan is the creator of spectacular carefully designed pop-art collages, in which, at a closer look, one can discover interesting details that might escape an inattentive glance. Ovidiu was born in 1983 in the comunist Bucharest, Romania, where he lived and studied architecture. His passion for art started at an early age but the University of Architecture influenced him to start producing recycled magazine collages as a step forward from his previous mix media artworks (digital, graffiti and acrylic). The result was so exciting that, ever since, he has been more fascinated by the torn pieces of paper than paints. Artworks of great architects like Le Corbusier and Friedensreich Hundertwasser were the starting point of his inspiration for his collage art technique as a personal manner to express his visual concepts. He enjoys working with nothing but recycled magazines and all pieces are manually tear or cut apart and glued to the canvas. @ovidiu.solcan has a large audience on Instagram – one of his major ways of exposing his art. As in real life Ovidiu’s artworks have been shown in exhibitions like: - ARTWALK STREET FESTIVAL – Bucharest 2017 & 2018 - North Sea Jazz Festival Rotterdam 2019 - #Brancusi heARTbeat #5th Edition @ Qreator Bucharest 2019 & 2020 - MONEY GO ROUND – Rosso Gallery 2020 – Rome - Luxury The Concept Store 2020 – Hamburg - Pavot Gallery 2020 – Bucharest Ovidiu had a solo studio gallery where his creative process was exhibited live as an installation at The Grand Avenue – Marriott in March - August 2018. During 2019 Ovidiu had a project sharing the joy of collage creation in partnership with Mastercard and Daruieste Viata Association. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

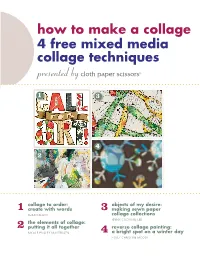

How to Make a Collage 4 Free Mixed Media Collage Techniques Presented by Cloth Paper Scissors®

how to make a collage 4 free mixed media collage techniques presented by cloth paper scissors® 1 3 4 2 collage to order: objects of my desire: 1 create with words 3 making sewn paper SUSAN BLACK collage collections JENNY COCHRAN LEE the elements of collage: 2 putting it all together reverse collage painting: NICOLE PAISLEY MARTENSEN 4 a bright spot on a winter day HOLLY CHRISTINE MOODY In “Objects of My Desire: Making Sewn Paper Collage Collections,” Jenny Cochran Lee explores how to How to Make a Collage: turn paper scraps into collage art 4 Free Mixed Media treasures. Collage Techniques presented by Finally, Holly Christine Moody Cloth Paper Scissors® offers an easy collage project that ONLINE EDITOR Cate Prato will help you whittle down your decorative paper stash in a fun CREATIVE SERVICES way. In “Reverse Collage Painting,” DIVISION ART DIRECTOR Larissa Davis PHOTOGRAPHER Larry Stein you make a paper collage on a substrate, apply gel medium, Projects and information are for inspiration and personal use only. Interweave Press is not responsible hat is collage art? A and then paint over it. The magic for any liability arising from errors, omissions, or whole lot of fun! At happens when you swipe away mistakes contained in this eBook, and readers should proceed cautiously, especially with respect to technical the most basic level, some of the paint to reveal the information. wyou can make a collage with paper, collage designs below. © F+W Media, Inc. All rights reserved. F+W Media glue, and a substrate like a canvas grants permission for any or all pages in this eBook to With How to Make a Collage: 4 Free or watercolor paper. -

Hôtel Marcel Dassault

ART MODERNE PARIS MAISON DE VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES - AGRÉMENT N° 2001-005 7, Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées – 75008 Paris PARIS – HÔTEL MARCEL DASSAULT Tél. : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 20 – Fax : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 21 MARDI 8 DÉCEMBRE 2009 www.artcurial.com – [email protected] MARDI 8 DÉCEMBRE 2009 – 20H30 01692 Mep-p-1-39 11/11/09 10:13 Page 1 ART MODERNE PARIS - HÔTEL MARCEL DASSAULT MARDI 8 DÉCEMBRE 2009 - 20H30 Mep-p-1-39 11/11/09 10:13 Page 2 Mep-p-1-39 11/11/09 10:13 Page 3 PARIS - HÔTEL MARCEL DASSAULT 7, Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées, 75008 Paris Téléphone pendant l’exposition : +33 (0) 1 42 99 20 59 COMMISSAIRE PRISEUR : Françis Briest SPÉCIALISTE : Violaine de La Brosse-Ferrand, +33 (0) 1 42 99 20 32 [email protected] ORDRE D’ACHAT ENCHÈRES PAR TÉLÉPHONE : Marianne Balse, +33 (0) 1 42 99 20 51 [email protected] COMPTABILITÉ VENDEURS : Sandrine Abdelli, +33 (0) 1 42 99 20 06 [email protected] COMPTABILITÉ ACHETEURS : Nicole Frerejean, +33 (0) 1 42 99 20 45 [email protected] EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES : Vendredi 4 décembre 11h - 19h Samedi 5 décembre 11h - 19h Dimanche 6 décembre 11h - 19h Lundi 7 décembre 11h - 19h VENTE : Mardi 8 décembre 20h30 CATALOGUE VISIBLE SUR INTERNET : www.artcurial.com VENTE N° 01692 Mep-p-1-39 11/11/09 10:13 Page 4 Mep-p-1-39 11/11/09 10:13 Page 5 ASSOCIÉS DÉPARTEMENT ART MODERNE Francis Briest, Co-Président ET ART CONTEMPORAIN Hervé Poulain Direction : Francis Briest François Tajan, Co-Président DIRECTEURS ASSOCIÉS Violaine de La Brosse-Ferrand ART MODERNE : Martin Guesnet Violaine de -

Picture Collage with Genetic Algorithm and Stereo Vision

IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 8, Issue 4, July 2011 ISSN (Online): 1694-0814 www.IJCSI.org 1 Picture Collage with Genetic Algorithm and Stereo vision Hesam Ekhtiyar1, Mahdi Sheida2 and Mahmood Amintoosi3 1 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Sabzevar Tarbiat Moallem University, Sabzevar, Iran, [email protected] 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Sabzevar Tarbiat Moallem University, Sabzevar, Iran, [email protected] 3 Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, Sabzevar Tarbiat Moallem University, Sabzevar, Iran, [email protected] Abstract In this paper, a salient region extraction method for creating picture collage based on stereo vision is proposed. Picture collage is a kind of visual image summary to arrange all input images on a given canvas, allowing overlay, to maximize visible visual information. The salient regions of each image are firstly extracted and represented as a depth map. The output picture collage shows as many visible salient regions (without being overlaid by others) from all images as possible. A very efficient Genetic algorithm is used here for the optimization. The experimental results showed the superior performance of the proposed method. Fig. 1 LEFT IMAGES OF SOME STEREO IMAGES USED IN THIS PAPER. Keywords: Picture Collage, Image Summarization, Depth Map visible or the images are occluded, the importance of 1. Introduction regions are discarded. An approach named saliency-based visual attention model Detection of interesting or ”salient” regions is a main sub- [2] is used in [1] for extracting interesting regions. This problem in the context of image tapestry and photo model combines multi scale image features (color, texture, collage.