Stone Construction in Grand Marais Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brick Installation Instructions DESIGNED by NATURE

Brick Installation Instructions DESIGNED BY NATURE. PERFECTED BY BOULDER CREEK.® 8282 Arthur Street NE Minneapolis , MN 55432 • 763-786-7138 • Fax 763-786-7276 • www.bouldercreekstone.com Getting Started INSTRUCTIONS BRICK INSTALLATION Congratulations on your decision to enhance the look of your home with Boulder Creek Brick products. Boulder Creek Brick products are made from a lightweight concrete material that replicates the look and texture of natural brick, and offers the benefit of being able to be installed directly to any surface. Calculating Materials Necessary If you haven’t already purchased your materials, you may be wondering how much Boulder Creek Brick will be necessary to complete your project. • First, measure the square footage of the total area to be covered by brick. • If you will be using corners on your project, plan for Example: each linear foot of corner pieces to cover ¾ square Total Surface Area= 100 sf foot of area. Corner Height = 8 ft. 8 ft. corner • Example: If you had a 100 square foot wall with an 8 8 x ¾ sf = 6 sf foot corner, the corner pieces would cover 6 square (Coverage by corners) 100 sf area feet of the wall. So, subtracting 6 from 100, you would 100 sf - 6 sf = 94 sf need 94 square feet of flat brick to cover the face of the wall, and 8 linear feet of corner pieces. Tips Some things to keep in mind before, during and after the installation process: Keep the Brick Clean During Installation Check Local Building Codes • Keep your hands clean. • Building codes vary from area to area. -

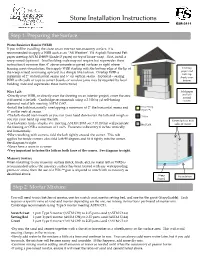

Stone Installation Instructions ESR-3111

Stone Installation Instructions ESR-3111 Step 1: Preparing the Surface Water Resistive Barrier (WRB) If you will be installing the stone on an exterior non-masonry surface, it is recommended to apply a WRB such as an “All Weather” 15# Asphalt Saturated Felt paper meeting ASTM D4869 (Grade D paper) on top of house wrap. First, install a weep screed (optional – local building code may not require but supersedes these instructions) no more than 4” above concrete or paved surfaces or right where framing meets foundation, then apply WRB starting with the bottom edge at the lip of Overlap the weep screed continuing upward in a shingle like fashion. Overlap WRB a paper and lath top minimum of 2” on horizontal seams and 6” on vertical seams. (optional – sealing sheets over WRB with caulk or tape to corner boards or window jams may be required by local bottom building code and supersedes these instructions) Wire Lath Fold paper •Directly over WRB, or directly over the sheeting on an interior project, cover the area and lath around with metal wire lath. Cambridge recommends using a 2.5 lb/sq yd self-furring corners diamond metal lath meeting ASTM C847. •Install the lath horizontally overlapping a minimum of 2” the horizontal seams and House Wrap (Tyvek ™) 6” on the vertical seams. •The lath should feel smooth as you run your hand down over the lath and rough as 15# Felt you run your hand up over the lath. Fasten lath on both •Use fasteners (nails, staples, etc. meeting ASTM C1063 sec.7.10.2) that will penetrate Metal Lath sides of corner the framing or OSB a minimum of 1 inch. -

A Home Away from Home at Grand Beach, Manitoba

Prairie Perspectives 135 A home away from home at Grand Beach, Manitoba John Selwood, University of Winnipeg Matthew Tonts, University of Western Australia Abstract: From its inception, Grand Beach, Manitoba, quickly became one of Western Canada’s foremost recreational, cottage resort localities and it has regained that position despite many years of neglect and abuse. Dominion government surveyors were the first to recognize the recreational possibilities of the beach, but this potential was not realized until the Canadian Northern Railway extended a line up the eastern side of Lake Winnipeg. Under a leasing arrangement with the provincial government, the railway company developed Grand Beach peninsula into an extremely popular lakeside resort and camping area, which during its heyday, was visited by countless thousands of excursionists and longer-term vacationers. This paper focuses on the development of the ‘Campsite’, an area initially created for temporary summer campers, but which was soon converted to leasehold lots available for long-term cottage development. Although the area is now part of Grand Beach Provincial Park, the cottages built in the old campground still remain. However, they are now being progressively upgraded, converted into more permanent fixtures, and many adapted for year-round use. Surveys of cottagers identify some interesting ownership patterns and reveal the strength of attachment that many of the predominantly urban residents have for their cottages or second homes, as they are commonly referred to in the academic literature. Introduction Although it is best known as a popular day resort area, Grand Beach is also one of Manitoba’s more important areas of cottage development, having been developed nearly a century ago during the First World War. -

Thin Cut Installation

“Natural Stone for any place and every space.” In addition to our line of full veneer, Semco StoneR also offers our ThinCutTM Natural Stone Veneer. ThinCutTM is available in depths that average one inch thick and is only one quarter the weight of full veneer. The reduced weight allows this veneer to be installed where full veneer cannot be used or is too difficult, such as dormers, gables, and existing interior and exterior structures. ThinCutTM can be applied to any structurally sound surface, including any masonry surface, concrete block, brick, cement, wallboard, plywood, paneling or metal buildings. ThinCutTM is durable, beautiful, and adds value to any home or business. CALCULATING NECESSARY MATERIALS: SCRATCH COAT, MORTAR & GROUT: Begin by guring the square footage of the area Example: Dry mix the sand and the cement together to you plan to cover with stone. If your project avoid creating clumps in the mixture. Add water Total Surface Area = 100 sq. ft. includes corner stones, deduct .75 square foot slowly to the mixture a little at a time, continually Corner Height = 9’ mixing until you have achieved the consistency of for each linear foot of corners that you will (9 x .75 = 6.75) utilize. Semco’s ThinCutTM Natural Stone Veneer a paste or whipped potatoes. Mix a minimum of 5 100 sq. ft. minutes. is packaged assuming a 1/2” mortar joint. If - 6.75 sq. ft. your joint will vary from this number you must 9’ Corner 93.25 sq. ft. MIXING AND APPLYING THE SCRATCH COAT: adjust your quantities accordingly. Scratch Coat: 1 part Type S Masonry Cement to 93.25 sq. -

How Was It Made?

HOW WAS IT MADE? HURRICANE SANDY DAMAGE CUBA RECOVERY IN THE EASTERN REGION SYSTEMATIZATION EXPERIENCES Compilers Erly Arner Reyes/ Universidad de Oriente/ Alkaid Benítez Pérez/ Universidad de Holguín/ OIKOS/ Proyecto “Asistencia de emergencia en la rehabilitación de viviendas y reducción de riesgos en los mu- nicipios Mayarí y Rafael Freyre”/ Andrés Olivera Ranero/ Universidad Central de Las Villas/ Marilyn Fernández Pérez/ ONU-Hábitat Cuba Colaborators Francisco R. Grajales Lira/ Asociación Cubana de Producción Animal (ACPA) / Santiago de Cuba/ Proyecto ACPA y WELTHUNGERHILFE (Alemania): “AYUDA HUMANITARIA PARA FAMILIAS NECESITADAS Y REHABILITACION DE LA PRODUCCION AGRICOLA EN AREAS RURALES AFECTADAS POR EL HURACAN SANDY”/Guillermo Tasé Cámbara/ Asociación Cubana de Producción Animal (ACPA) /Ugo Puccio/ GVC – Holguín/ Proyecto “Recuperación de los medios de subsistencia familiar, de la vivienda rural y de los servicios al medioambiente, afectados por el huracán Sandy” - ECHO/CUB/BUD/2012/91006/ Raúl Figueredo Reyes/ UNAICC Holguín/ Raúl Solozano Guerrero /CARE – UNAICC– UPIV Holguín/ Progra- ma de Asistencia de Emergencia a los afectados por el Huracán Sandy en la provincia de Holguín/ María de los Ángeles Romero Chirino/ Unidad Provincial Inversionista de la Vivienda Santiago de Cuba/ Wal- do Andrés Vicente Hernández/ Unidad Provincial Inversionista de la Vivienda Santiago de Cuba/ José Angel Despaigne Quesada/ Unidad Municipal Inversionista de la Vivienda, Palma Soriano, Santiago de Cuba/ Sergio Peña Macías/ Cruz Roja Cubana Provincial Santiago de Cuba/ Juan Manuel Pascual Menéndez/ Profesor Titular Facultad de Construcciones Universidad de Oriente/ Beatriz Hadad Pérez/ Profesora Instructora Facultad de Construcciones Universidad de Oriente/ Aris Arias Batalla/ Cruz Roja Cubana Provincial Santiago de Cuba/ Mayté Wong Rodríguez/ UPIV Holguín. -

Product Users Guide

MOUNTAIN STONE® Products PRODUCT USERS GUIDE Mountain Stone® Products P.O. Box 20308 42102 4301 Industrial Road Bowling Green, KY. 42101 (270) 796-6123 (270) 796-6131 (800) 781-0277 Local Fax Nationwide Product Users Guide 1 STONE TEST RESULTS BY Mountain Stone® Products 4301 Industrial Road Bowling Green, KY. 42101 Product Testing Results The following tests were performed by: ATEC Associates (The American Testing and Engineering Corporation) located in Nashville, Tennessee. Absorption Test- ASTM C-67 Flexural Strength - ATSM C-348 Absorption Percentage Average=3.3% Flexural Strength ( psi) –average - 117 Compressive Strength – ASTM C- 67 Freeze -Thaw - ASTM C- 67-83 Compressive Strength Average = 3260 psi *No noticeable cracking occurred. Thermal Properties Efflorescence Test - ATSM C-67 sec.10 Thickness (inches) = 1.587 *Not efflorescenced Density (pcf) = 63.17 R-factor ** = 1.38 **R factor is based on the thickness in accordance with ASTM C 177-71. Average thickness may vary, which will result in R-factors varying. The insulative quality is equal to 6” of common brick. Other Tests •= Non-combustible stone, showed zero flame spread and no smoke developed. •= Colorfastness: During testing of stone no undesirable change in color was noted. Installation Procedures 1. PREPARING THE SURFACE Due to its light weight, Mountain Stone can be applied to any structurally sound surface, (except Sheet Rock) and needs no special structural foundation alteration or additions. Apply Mountain Stone directly to the surface of concrete, block, brick, and other masonry surfaces only if the surfaces are clean, unpainted, unsealed, and untreated. All other surfaces must be covered with a 2.5# Galvanized Diamond metal lath. -

MASTER CATALOG Tools for the Remodeling, Restoration and Building Trades

HydeCatalog 9/7/07 11:14 AM Page 1 MASTER CATALOG Tools for the Remodeling, Restoration and Building Trades For a better finish, start with HYDE™. HydeCatalog 9/7/07 11:14 AM Page 2 by memorable merchandising product strength and durability Serious and advertising directly to are often backed by a lifetime Tools for your customers. guarantee. America’s Favorite Brand Tap into the loyal following PAINT & SURFACE PREP 5 Serious Our brand strength has never Hyde Tools has been building for Spray Tools, Paint Shields, Scrapers, Putty been stronger in paint and wall- generations. Stock HYDE® brand Knives, Multi-use Tools, Cleaning Brushes Sales covering hand tools. HYDE® is tools and you can be sure your REPAIR 35 America’s favorite brand in these customers will come back RePairs™ Value Packs, Wall Repair Tools, Caulk categories, chosen two to one by frequently and buy often. Repair Tools, Glass Repair Tools Growth contractors over any other brand DRYWALL 45 HYDE® is the brand of choice for for scraping, patching, taping Are You Serious About ® Joint Knives, Taping Knives, Corner Tools, retailers and wholesalers who and coating surfaces. Whether Sales? Get HYDE Pointing Knives, Hawks, Mixers, Mud Pans, are serious about growing sales. purchased by professionals or Call our customer service Saws, Joint Tape Our high-quality tools are com- homeowners, our tools are department at 800-USA-HYDE MASONRY & CONCRETE 67 petitively priced and supported considered “serious tools for (872-4933) or 508-764-4344 Concrete, Cement and Brick Tools: Trowels, serious users.” Our superior for details. Pointers, Edgers, Groovers, Floats WALLCOVERING 75 Scoring Tool, Shavers, Scrapers, Shears, Brushes, Guides, Smoothing Tools, Rollers Every label bears the distinctive HYDE® branding. -

Download the 2021/2022 Travel Guide

Rural Municipality of Coldwell Great bird watching and hiking trails Lundar Agricultural Fair Snowmobiling Historical sites Hunters Paradise Great Camping and fun in the sun at our Beaches Lundar Community Swimming Pool www.lundar.ca Contents “Interlake Festivals” 8 “Interlake Gems” 12 2021 Manitoba’s Interlake Travel Guide is presented to you by “Outdoor Magic” 14 Interlake Tourism Association Wild Wanderings 14 Interlake Tourism Association Phone: 204-322-5378 Toll Free: 1-877-468-3752 Nature & Wildlife Viewing 18 [email protected] interlaketourism.com Birding in the Interlake 20 Hitting the Trails 22 Geocaching 27 Creative Manager Gail McDonald Fishing & Hunting 27 Design S.Thompson Designs Inc. Content Writer Gail McDonald Beaches, Lakes & Parks 30 Advertising Sales Gail McDonald Administration Melissa Van Soelen Riding the Waves 36 Photography Guy Barrett Interlake Golf Courses Sue Bauernhuber 40 Jessie Carbal Halloween Hauntings 41 Sheri Crockatt Sherry Giesbrecht Winter Wonderland 42 Todd Goranson Paul Hammer Ben Hewson “Reflections of the Past” 44 Steve Langston Gail McDonald Historical Sites & Museums 46 Y Nuestro Arahan Todd Scott Other Fascinating Interlake Heritage 55 Fraser Stewart Heritage Churches Melissa Van Soelen 56 Special Thanks to Interlake Tourism Association “Larger Than Life” 59 members for their contributions: Heather Hinam - Second Nature, Creative Interpretation, Dave Roberts [formerly of Manitoba “The Arts Alive” 60 Sustainable Development], Gerry Hammond of Spruce Sands RV Resort, Jacques Bourgeois of Oak Hammock Marsh “Tasty Temptations” 64 Front Cover Photo: Prairie Sea Kayak Adventures, Photo by Rob Jantz “Fresh Local Foods” 70 Thank you to all individuals and communities that submitted information to assist ITA in bringing you “In Our Communities” 72 this Travel Ideas Guide. -

Competency Standards For

COMPETENCY STANDARDS FOR MASON Unit No Unit Title 1. Set-out building / structures 2. carry out brick work 3. Carry out block work 4. Lay damp proof course 5. Carry out concreting work 6. Carry out paving work 7. Plaster surfaces 8. Render floor surfaces 9. Carry out decorative plastering work 10. Fix door and window frames 11. Lay drains 12. Erect scaffolds 13. Carry out tiling work 14. Carry out arch work, decorative brick work, rubble and kabook structure work DESCRIPTION OF AN MASON Mason will be working front line of the construction industry. Masons who are competent in this standard will be able to perform skilled masonry work, building, altering and repairing brick, stones tile or ceramic structure and surfaces COMPETENCY STANDARD DEVELOPMENT PROCESS The competencies were determined based on the analysis of the tasks expected to be performed by the bar bender in the Maldives. The task analysis was based on the existing job descriptions used in both private and public sector. Competency standards used for similar type of training in other countries were also examined. 1 UNIT TITLE Set-out building / structures DESCRIPTOR This unit covers the competencies required to set out building and other related structures. It includes operations, which require basic tools, equipment and techniques other than Theodelite and Engineers level ensuring safety to self, others and property. CODE CON08S2U01VI Level 4 Credit 5 ELEMENTS OF COMPETENCE PERFORMANCE CRITERIA 1. Read and interpret 1.1. Notations, abbreviations, symbols, dimensions and drawings scales read, interpreted & drawings selected 1.2. Elevations, sectional elevations, detailed drawings & schedules interpreted & centre line dimensions calculated by adding or subtracting half of the width of the wall dimensions as shown in the drawing 2. -

California Prop 65 Notice

CALIFORNIA PROPOSITION 65 NOTIFICATIONS Proposition 65 is a California state law requiring warnings to California consumers when they may be exposed to chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer, congenital disabilities, and/or reproductive harm. Because our products are sold in California, Hyde Tools complies with Proposition 65. To ensure compliance, we include the below warning on any of our products which contain chemicals known to the state of California to cause certain harms. WARNING: These products can expose you to chemicals that are known to the State of California to cause cancer and/or reproductive harm. Find more information here: https://www.p65warnings.ca.gov/. If you have any questions regarding Proposition 65 and Hyde Tools’ products, please contact our Customer Service Department by phone (1-800-872- 4933) or email ([email protected]) Hyde Item UPC Code Product Description Warning Chemicals/Materials Explanation Black & Silver® 1-1/4" 02080 079423020803 Lead Brass has a small amount of lead Stiff Chisel Putty, Brass ⚠ WARNING: Cancer Black & Silver® 1-5/16" 02215 079423022159 Lead Brass has a small amount of lead Stiff Chisel Putty, Brass ⚠ WARNING: Cancer Black & Silver® 2" Stiff 02320 079423023200 Lead Brass has a small amount of lead Putty, Brass ⚠ WARNING: Cancer Black & Silver® 3" Stiff 02420 079423024207 Lead Brass has a small amount of lead Chisel Scraper, Brass ⚠ WARNING: Cancer Black & Silver® 5-in-1, 02975 079423029752 Lead Brass has a small amount of lead Brass ⚠ WARNING: Cancer 6 -

Studies on the Bryophites of Southern Manitoba. III. Collections From

: I JOURNAL OF THE NEW ENGLAND BOTANICAL CLUB Conducted and published for the Club, by ALBION REED HODGDON, Editor-in-Chief ROLLA MILTON TRYON RADCLIFPE BARNES PIKE STEPHEN ALAN SPONGBERG GERALD JOSEPH GASTONY I.* Editon ALFRED LINN BOGLE RICHARD EDWIN WEAVER VoL 76 March, 1974 No. 805 CONTENTS The Phytogeography and Systematics of Xanthisma tex- anum D. C. (Asteraceae) ; Proper Usage of Intraspecific Categories John C. Semple .. A White-Flowered Form of Utricularia purpurea C. Barre Hellquist „ 19 On the Scientific Name of the Longleaf Pine Daniel B. Ward 20 The Occurrence of Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum (L.) Richard) in Suffolk County, Long Island, New York Edward J. Hehre and Peter M. Bollard 25 Ssefo #«qlattfc 3£ Clttlr, 3n Oxfo 02138 STUDIES ON THE BRYOPHYTES OF SOUTHERN MANITOBA III. COLLECTIONS FROM GRAND BEACH PROVINCIAL PARK Paul W. Stringer and Muriel H. L. Stringer Grand Beach Provincial Park lies approximately 57 miles north of Winnipeg. The entire park, which covers 59,000 acres, is in the Manitoba Lowlands Section of the Boreal Forest Region (Rowe, 1959). Three miles of the area fronts on Lake Winnipeg. The underlying bedrock is palaeozoic limestone, and the overlying beds are modified till, or lacustrine clays deposited in glacial Lake Agassiz. Most soils have a high lime content. On the flat, poorly drained areas, black spruce (Picea maridTia (Mill.) BSP.) and tamarack (Larix laricina (Du Roi) K. Kich) forest prevail, while on the better drained alluvial strips bordering the rivers and creeks, white spruce (Picea glauca (Moench) Voss), aspen (Populus tremaloides Michx.) and balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera L.) pre- dominate. -

International Handbook of Occupational Therapy Interventions Ingrid Söderback Editor

International Handbook of Occupational Therapy Interventions Ingrid Söderback Editor International Handbook of Occupational Therapy Interventions Editor Ingrid Söderback Associate Professor in Occupational Therapy and Rehabilitation Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden and University Lecturer Emerita Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden Home address: Sickla Kanalgata 31 nb SE 13165 Nacka E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-387-75423-9 e-ISBN: 978-0-387-75424-6 DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-75424-6 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2009927464 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) To be occupied is a fundamental right in every human being’s life. The occupational therapists’ main professional role is to encourage the clients’ occupational performances. To occupational therapy students, occupational therapists, and members of rehabilitation and health care teams, who are professionally working to improve their clients’ health and wellness, and to stakeholders responsible for the administration of occupational therapy, worldwide.