AMRC Journal Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1962 FMAC SS.Pdf

WIND DRUM The music of WIND DRUM is composed on a six-tone scale. In South India, this scale is called "hamsanandi," in North India, "marava." In North India, this scale would be played before sunset. The notes are C, D flat, E, F sharp, A, and B. PREFACE The mountain island of Hawaii becomes a symbol of an island universe in an endless ocean of nothingness, of space, of sleep. This is the night of Brahma. Time swings back and forth, time, the giant pendulum of the universe. As time swings forward all things waken out of endless slumber, all things grow, dance, and sing. Motion brings storm, whirlwind, tornado, devastation, destruction, and annihilation. All things fall into death. But with total despair comes sudden surprise. The super natural commands with infinite majesty. All storms, all motions cease. Only the celestial sounds of the Azura Heavens are heard. Time swings back, death becomes life, resurrection. All things are reborn, grow, dance, and sing. But the spirit of ocean slumber approaches and all things fall back again into sleep and emptiness, the state of endless nothingness symbolized by ocean. The night of Brahma returns. LIBRETTO I VI Stone, water, singing grass, Flute of Azura, Singing tree, singing mountain, Fill heaven with celestial sound! Praise ever-compassionate One. Death, become life! II VII Island of mist, Sun, melt, dissolve Awake from ocean Black-haired mountain storm, Of endless slumber. Life drum sing, III Stone drum ring! Snow mountain, VIII Dance on green hills. Trees singing of branches IV Sway winds, Three hills, Forest dance on hills, Dance on forest, Hills, green, dance on Winds, sway branches Mountain snow. -

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Balade Dans La Galaxie Beastie Boys » OWNI, News, Augmented

BALADE DANS LA GALAXIE BEASTIE BOYS LE 11 MAI 2011 GWEN BOUL Le 2 mai, le très attendu nouvel album des Beastie Boys, "Hot Sauce Comittee pt.2" est sorti. Pour l'occasion, nous vous proposons de replonger dans la galaxie du trio New Yorkais. Hot Sauce Committee part 2, le nouvel album des Beastie Boys, est enfin sorti. Le groupe avait plusieurs fois reporté la sortie de l’album. Après une sortie déjà décalée en 2009 pour cause de Crabe qui s’invitait dans la gorge d’Adam Yauch, alias MCA, le groupe refaisait le coup en 2010. « Pas avant 2011 les amis ! ». Promesse finalement tenue avec un disque qui réjouit les fans. C’est l’occasion pour OWNImusic de republier la petite balade dans la galaxie Beastie Boys, balade guidée par Gwen de Centrifugue. Un univers gigantesque, aux astres multiples et empli d’univers parallèles. Décollage. Les grands champs gravitationnels Débutons notre périple cosmique par ceux qui ont modelé cette galaxie : les inspirateurs et les producteurs. LEE SCRATCH PERRY Le producteur incontournable dans l’histoire du reagge et du dub. Celui-ci fit une apparition remarquée sur Hello Nasty avec le morceau Dr Lee PhD . Une association débutée lors d’une première partie des Beastie assurée par Lee Perry, à l’occasion d’une tournée au Japon en 1996. Mais l’influence est plus ancienne et remonte à l’EP Cooky Puss en 1983, qui comportait les morceaux dub-reggae Beastie Revolution et Bonus Batter Edit : et l’on retrouve également un sample de Dub Revolution sur Ill Communication. -

Dissonance Treatment in Fuging Tunes by Daniel Read

NA7c DISSONANCE TREATMENT IN FUGING TUNES BY DANIEL READ FROM THE AMERICAN SINGING BOOK AND THE COLUMBIAN HARMONIST THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the' North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Scott G. Sims, B.M. Denton, Texas May, 1987 4vv , f\ Sims, Scott G., Dissonance Treatment in Fuging Tunes by Daniel Read from The American Singing Book and The Columbian Harmonist. Master of Music (Music Theory), May, 1987, 101 pp., 2 tables, 8 figures, 44 musical examples, 83 titles. This thesis treats Daniel Read's music analytically to establish style characteristics. Read's fuging tunes are examined for metric placement and structural occurrence of dissonance, and dissonance as text painting. Read's comments on dissonance are extracted from his tunebook introductions. A historical chapter includes the English origins of the fuging tune and its American heyday. The creative life of Daniel Read is discussed. This thesis contributes to knowledge of Read's role in the development of the New England Psalmody idiom. Specifically, this work illustrates the importance of understanding and analyzing Read's use of dissonance as a style determinant, showing that Read's dissonance treatment is an immediate and central characteristic of his compositional practice. Copyright by Scott G. Sims 1987 iii PREFACE The author wishes to thank The Lorenz Publishing Company for use of the following article: Metcalf, Frank, "Daniel Read and His Tune," The Choir Herald, XVII (April, 1914) , 124, 146-147. Copyright 1914, Renewal Secured, Lorenz Publishing Co., Used by Permission. -

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus the Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, Conducting

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus The Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, conducting ALAN HOVHANESS is one of those composers whose music seems to prove the inexhaustability of the ancient modes and of the seven tones of the diatonic scale. He has made for himself one of the most individual styles to be found in the work of any American composer, recognizable immediately for its exotic flavor, its masterly simplicity, and its constant air of discovering unexpected treasures at each turn of the road. Meditation on Orpheus, scored for full symphony orchestra, is typical of Hovhaness’ work in the delicate construction of its sonorities. A single, pianissimo tam-tam note, a tone from a solo horn, an evanescent pizzicato murmur from the violins (senza misura)—these ethereal elements tinge the sound of the middle and lower strings at the work’s beginning and evoke an ambience of mysterious dignity and sensuousness which continues and grows throughout the Meditation. At intervals, a strange rushing sound grows to a crescendo and subsides, interrupting the flow of smooth melody for a moment, and then allowing it to resume, generally with a subtle change of scene. The senza misura pizzicato which is heard at the opening would seem to be the germ from which this unusual passage has grown, for the “rushing” sound—dynamically intensified at each appearance—is produced by the combination of fast, metrically unmeasured figurations, usually played by the strings. The composer indicates not that these passages are to be played in 2/4, 3/4, etc. but that they are to last “about 20 seconds, ad lib.” The notes are to be “rapid but not together.” They produce a fascinating effect, and somehow give the impression that other worldly significances are hidden in the juxtaposition of flow and mystical interruption. -

Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective Alejandro Marcelo Drago University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Drago, Alejandro Marcelo, "Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective" (2008). Dissertations. 1107. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ALEJANDRO MARCELO DRAGO 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. -

Extract from Text

DISCOVER CHORAL MUSIC Contents page Track List 4 A Brief History of Choral Music , by David Hansell 13 I. Origins 14 II. Early Polyphony 20 III. The Baroque Period 39 IV. The Classical Period 68 V. The Nineteenth Century 76 VI. The Twentieth Century and Beyond 99 Five Centuries of Choral Music: A Timeline (choral music, history, art and architecture, literature) 124 Glossary 170 Credits 176 3 DISCOVER CHORAL MUSIC Track List CD 1 Anon (Gregorian Chant) 1 Crux fidelis 0.50 Nova Schola Gregoriana / Alberto Turco 8.550952 Josquin des Prez (c. 1440/55–c. 1521) 2 Ave Maria gratia plena 5.31 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.553428 John Taverner (c. 1490–1545) Missa ‘Gloria Tibi Trinitas’ 3 Sanctus (extract) 5.28 The Sixteen / Harry Christophers CDH55052 John Taverner 4 Christe Jesu, pastor bone 3.35 Cambridge Singers / John Rutter COLCD113 4 DISCOVER CHORAL MUSIC Thomas Tallis (c. 1505–1585) 5 In manus tuas, Domine 2.36 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550576 William Byrd (c. 1540–1623) 6 Laudibus in sanctis 5.47 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550843 Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525/6–1594) Missa ‘Aeterna Christi Munera’ 7 Agnus Dei 4.58 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550573 Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611) 8 O magnum mysterium 4.17 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550575 Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) Vespers of the Blessed Virgin 9 Laudate pueri Dominum 6.05 The Scholars Baroque Ensemble 8.550662–63 Giacomo Carissimi (1605–1674) Jonas 10 Recitative: ‘Et crediderunt Ninevitae…’ 0.25 11 Chorus of Ninevites: ‘Peccavimus, -

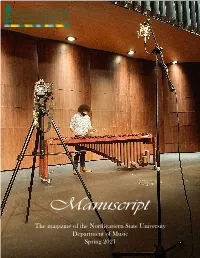

Manuscript Newsletter, Spring 2021 Edition

Manuscript The magazine of the Northeastern State University Department of Music Spring 2021 Contents 2 Welcome from the Chair Features 3 Guest Artists 5 NSU @ OkMEA 6 New Student Lounge & Opera Workshop 7 Green Country Jazz Festival 9 “Can’t stop the Music” (AKA NSU Music during a global pandemic) 11 Announcement of a new music degree 12 Student News 13 Alumni Feature 14 In Memorium 15 Faculty News 17 Endowments, Scholarships, & Donors Musicians: we are the most romantic of all artists. We believe in, and chase the illusive, intoxicating, unseen magic/beauty that exists in the universe. We are conduits for this magic/ beauty that has the ability to stir emotions that are fundamental to what it means to be human and alive. Here’s to us all....! - Dr. Ron Chioldi Welcome FROM THE CHAIR Spring 2021 marks the end of an academic year unlike any other. It was difficult. It was certainly stressful. So many modifications were made to our normal operating procedures due to the pandemic. Some of these modifications will inform how we operate in the future. Others, I hope we never have to implement ever again. Our faculty, staff, and students were resilient in the face of highly pressurized circum- stances. I want to thank them for their grace, adaptability, and understanding as things constantly changed. Early on in the pandemic, the performing arts were singled out as being particularly risky for infection. We took measures to ensure the safety of our faculty, staff, and students as best we could under state, local, and university protocols. -

Alan Hovhaness: Exile Symphony Armenian Rhapsodies No

ALAN HOVHANESS: EXILE SYMPHONY ARMENIAN RHAPSODIES NO. 1-3 | SONG OF THE SEA | CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE AND STRINGS [1] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 1, Op. 45 (1944) 5:35 SONG OF THE SEA (1933) ALAN HOVHANESS (1911–2000) John McDonald, piano ARMENIAN RHAPSODIES NO. 1-3 [2] I. Moderato espressivo 3:39 [3] II. Adagio espressivo 2:47 SONG OF THE SEA [4] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 2, Op. 51 (1944) 8:56 CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE AND STRINGS, Op. 344 (1980) AND STRINGS Kenneth Radnofsky, soprano saxophone [5] I. Andante; Fuga 5:55 SYMPHONY NO. 1, EXILE [6] II. Adagio espressivo; Allegro 4:55 [7] III. Let the Living and the Celestial Sing 6:23 JOHN McDONALD piano [8] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 3, Op. 189 (1944) 6:40 KENNETH RADNOFSKY soprano saxophone SYMPHONY NO. 1, EXILE, Op. 17, No. 2 (1936) [9] I. Andante espressivo; Allegro 9:08 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [10] II. Grazioso 3:31 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR [11] III. Finale: Andante; Presto 10:06 TOTAL 67:39 RETROSPECTIVE them. But I’ll print some music of my own as I get a little money and help out because I really don’t care; I’m very happy when a thing is performed and performed well. And I don’t know, I live very simply. I have certain very strong feelings which I think many people have Alan Hovhaness wrote music that was both unusual and communicative. In his work, the about what we’re doing and what we’re doing wrong. archaic and the avant-garde are merged, always with melody as the primary focus. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

Norway's Jazz Identity by © 2019 Ashley Hirt MA

Mountain Sound: Norway’s Jazz Identity By © 2019 Ashley Hirt M.A., University of Idaho, 2011 B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Musicology. __________________________ Chair: Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz __________________________ Dr. Bryan Haaheim __________________________ Dr. Paul Laird __________________________ Dr. Sherrie Tucker __________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong-Cruz The dissertation committee for Ashley Hirt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: _____________________________ Chair: Date approved: ii Abstract Jazz musicians in Norway have cultivated a distinctive sound, driven by timbral markers and visual album aesthetics that are associated with the cold mountain valleys and fjords of their home country. This jazz dialect was developed in the decade following the Nazi occupation of Norway, when Norwegians utilized jazz as a subtle tool of resistance to Nazi cultural policies. This dialect was further enriched through the Scandinavian residencies of African American free jazz pioneers Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and George Russell, who tutored Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek. Garbarek is credited with codifying the “Nordic sound” in the 1960s and ‘70s through his improvisations on numerous albums released on the ECM label. Throughout this document I will define, describe, and contextualize this sound concept. Today, the Nordic sound is embraced by Norwegian musicians and cultural institutions alike, and has come to form a significant component of modern Norwegian artistic identity. This document explores these dynamics and how they all contribute to a Norwegian jazz scene that continues to grow and flourish, expressing this jazz identity in a world marked by increasing globalization. -

Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra Gabriel Prokofiev Teacher Pages

SECONDARY 10 PIECES PLUS! CONCERTO FOR TURNTABLES AND ORCHESTRA (5th MOVEMENT) by GABRIEL PROKOFIEV TEACHER PAGES CONCERTO FOR TURNTABLES AND ORCHESTRA (5TH MOVEMENT) BY GABRIEL PROKOFIEV http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p038md89 CONTEXT Gabriel Prokofiev is the grandson of Sergei Prokofiev, the famous Russian composer and contemporary of Shostakovich. Gabriel is a musician who has been involved in hip hop, dance, electro, grime, scratching and turntablism. He has become interested in the fusion of different styles of music and decided to write a Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra where sounds created by the orchestra could be combined with turntable techniques. Turntablism comes from the 1970’s Hip Hop style. The records on the turntables are scratched rhythmically, responding to the music being played: this technique is used in the Prokofiev concerto. The DJ manipulates the sounds on the vinyl records changing tonal and rhythmic patterns. The records used in the piece contain music samples of orchestral phrases. A concerto is an orchestral piece of music which features a soloist, or small group of soloists who are virtuoso performers. The soloist usually has the main ideas and maintains a dialogue with the orchestra throughout the music. As with any instrumentalist, the DJ requires plenty of practice to become skilful in the technique of manipulating sounds. The concerto usually contains a ‘cadenza’, which is a passage where the soloist can show off his or her skills. Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra was written in 2006 and was