Docunsfr REM=

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance

Gordon 1 Jessica Gordon 29 March 2010 Honors Thesis Everything was Beautiful at the Ballet: The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance During the mid-1860s, a ballet troupe from Paris was brought to the Academy of Music in lower Manhattan. Before the company’s first performance, however, the theatre in which they were to dance was destroyed in a fire. Nearby, producer William Wheatley was preparing to begin performances of The Black Crook, a melodrama with music by Charles M. Barras. Seeing an opportunity, Wheatley conceived the idea to combine his play and the displaced dance company, mixing drama and spectacle on one stage. On September 12, 1866, The Black Crook opened at Niblo’s Gardens and was an immediate sensation. Wheatley had unknowingly created a new American art form that would become a tradition for years to come. Since the first performance of The Black Crook, dance has played an important role in musical theatre. From the dream ballet in Oklahoma to the “Dance at the Gym” in West Side Story to modern shows such as Movin’ Out, dance has helped tell stories and engage audiences throughout musical theatre history. Dance has not always been as integrated in musicals as it tends to be today. I plan to examine the moments in history during which the role of dance on the Broadway stage changed and how those changes affected the manner in which dance is used on stage today. Additionally, I will discuss the important choreographers who have helped develop the musical theatre dance styles and traditions. As previously mentioned, theatrical dance in America began with the integration of European classical ballet and American melodrama. -

Fantasy & Science Fiction

Alphabetical list of Authors Clonmel Library Douglas Adams Kazuo Ishiguro Clonmel Library Issac Asimov PD James Ray Bradbury Robert Jordan Terry Brooks Kate Jacoby RecommendedRecommended Trudi Canavan Ursala K. Le Guin Arthur C Clarke George Orwell Susanna Clarke Anne McCaffery ReadingReading Philip K. Dick George RR Martin David Eddings Mervyn Peake Raymond E. Feist Terry Pratchett American Gods Philip Pullman Neil Gaiman Brandon Sanderson David Gemmell JRR Tolkein Terry Goodkind Jules Verne Robert A. HeinLein Kurt Vonnegut FantasyFantasy && Frank Herbert T.H. White Robin Hobb Aldous Huxley Clonmel Library ScienceScience FictionFiction Opening Hours & Contact Details Monday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Tuesday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Wednesday: 9.30 am – 8.00 pm Thursday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Friday: 9.30 am – 1pm & 2pm - 5pm Saturday: 10.00 am – 1pm & 2pm-5pm Phone: (052) 6124545 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.tipperarylibraries.ie/clonmel 11 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea AnAn IntroductionIntroduction Jules Verne First published 1869 toto FantasyFantasy French naturalist Dr. Aronnax embarks on an expedition to hunt down a sea monster, only to discover instead the && ScienceScience FictionFiction Nautilus, a remarkable submarine built by the enigmatic Captain Nemo. Together Nemo and Aronnax explore the antasy is a genre that uses magic and other supernatural forms underwater marvels, undergo a transcendent experience as a primary element of plot, theme, and/or setting. Fantasy is amongst the ruins of Atlantis, and plant a -

Twyla Tharp Th Anniversary Tour

Friday, October 16, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 17, 2015, 8pm Sunday, October 18, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour r o d a n a f A n e v u R Daniel Baker, Ramona Kelley, Nicholas Coppula, and Eva Trapp in Preludes and Fugues Choreography by Twyla Tharp Costumes and Scenics by Santo Loquasto Lighting by James F. Ingalls The Company John Selya Rika Okamoto Matthew Dibble Ron Todorowski Daniel Baker Amy Ruggiero Ramona Kelley Nicholas Coppula Eva Trapp Savannah Lowery Reed Tankersley Kaitlyn Gilliland Eric Otto These performances are made possible, in part, by an Anonymous Patron Sponsor and by Patron Sponsors Lynn Feintech and Anthony Bernhardt, Rockridge Market Hall, and Gail and Daniel Rubinfeld. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PROGRAM Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour “Simply put, Preludes and Fugues is the world as it ought to be, Yowzie as it is. The Fanfares celebrate both.”—Twyla Tharp, 2015 PROGRAM First Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers The Practical Trumpet Society Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company Antiphonal Fanfare for the Great Hall by John Zorn. Used by arrangement with Hips Road. PAUSE Preludes and Fugues Dedicated to Richard Burke (Bay Area première) Choreography Twyla Tharp Music Johann Sebastian Bach Musical Performers David Korevaar and Angela Hewitt Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company The Well-Tempered Clavier : Volume 1 recorded by MSR Records; Volume 2 recorded by Hyperi on Records Ltd. INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Second Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers American Brass Quintet Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

Twyla Tharp Goes Back to the Bones

HARVARD SQUARED ture” through enchanting light displays, The 109th Annual dramatizes the true story of six-time world decorations, and botanical forms. Kids are Christmas Carol Services champion boxer Emile Griffith, from his welcome; drinks and treats will be available. www.memorialchurch.harvard.edu early days in the Virgin Islands to the piv- (November 24-December 30) The oldest such services in the country otal Madison Square Garden face-off. feature the Harvard University Choir. (November 16- Decem ber 22) Harvard Wind Ensemble Memorial Church. (December 9 and 11) https://harvardwe.fas.harvard.edu FILM The student group performs its annual Hol- The Christmas Revels Harvard Film Archive iday Concert. Lowell Lecture Hall. www.revels.org www.hcl.harvard.edu/hfa (November 30) A Finnish epic poem, The Kalevala, guides “A On Performance, and Other Cultural Nordic Celebration of the Winter Sol- Rituals: Three Films By Valeska Grise- Harvard Glee Club and Radcliffe stice.” Sanders Theatre. (December 14-29) bach. The director is considered part of Choral Society the Berlin School, a contemporary move- www.harvardgleeclub.org THEATER ment focused on intimate realities of rela- The celebrated singers join forces for Huntington Theatre Company tionships. She is on campus as a visiting art- Christmas in First Church. First Church www.huntingtontheatre.org ist to present and discuss her work. in Cambridge. (December 7) Man in the Ring, by Michael Christofer, (November 17-19) STAFF PICK:Twyla Tharp Goes music of Billy Joel), and, in 2012, the ballet based on George MacDonald’s eponymous tale The Princess and the Goblin. Back to the Bones Yet “Minimalism and Me” takes the audience back to New York City in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the emergence of a rigor- Renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp, Ar.D. -

A Study of the Genre of T. H. White's Arthurian Books a Thesis

A Study of the Genre of T. H. White's Arthurian Books A Thesis for the Degree of Ph. D from the University of Wales Susan Elizabeth Chapman June 1988 Summary T. H. White's Arthurian books have been consistently popular with the general public, but have received limited critical attention. It is possible that such critical neglect is caused by the books' failure to conform to the generic norms of the mainstream novel, the dominant form of prose fiction in the twentieth century. This thesis explores the way in which various genres combine in The. Once alai Future King.. Genre theory, as developed by Northrop Frye and Alastair Fowler, is the basis of the study. Neither theory is applied fully, but Frye's and Fowler's ideas about the function of genre as an interpretive tool underpin the study. The genre study proper begins with an examination of the generic repertoire of the mainstream novel. A study of The. Qnce gknj Future King in relation to this form reveals that it exhibits some of its features, notably characterization and narrative, but that it conspicuously lacks the kind of setting typical of the mainstream novel. A similar approach is followed with other subgenres of prose fiction: the historical novel; romance; fantasy; utopia. In each case Thy Once angj Future King is found to exhibit some key features, unique to that form, although without sufficient of its characteristics to be described fully in those terms. The function of the comic and tragic modes within The. Qnce änd Future King is also considered. -

THE MANY FACES of MERLIN in MODERN FICTION Author(S): Christopher Dean Source: Arthurian Interpretations, Vol

THE MANY FACES OF MERLIN IN MODERN FICTION Author(s): Christopher Dean Source: Arthurian Interpretations, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Fall 1988), pp. 61-78 Published by: Scriptorium Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27868651 . Accessed: 09/06/2014 19:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Scriptorium Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Arthurian Interpretations. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.212.18.200 on Mon, 9 Jun 2014 19:11:41 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MANY FACES OF MERLIN IN MODERN FICTION1 Merlin, Arthur's enchanter and prophet, a figure ofmystery, ofmagic, and of awesome power, is a name that has been part of our literature formore than eight centuries. But the same creature is never conjured, for, as Jane Yolen says, was he not "a shape-shifter, a man of shadows, a son of an incubus, a creature of the mists" (xii)? Or, to quote Nikolai Tolstoy, as a "trickster, illusionist, philosopher and sorcerer, he represents an archetype to which the race turns for guidance and protection" (20). -

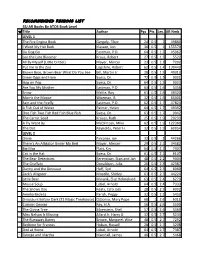

RECOMMENDED READING LIST SSJ AR Books by ATOS Book Level ✔️Title Author Pgs Pts Lev

RECOMMENDED READING LIST SSJ AR Books By ATOS Book Level ✔️Title Author Pgs Pts Lev. AR Nmb LEVEL 1 The Fire Engine Book Gergely, Tibor 24 0.5 1 49860 I Want My Hat Back Klassen, Jon 36 0.5 1 155570 Go Dog Go Eastman, P.D. 64 0.5 1.2 45962 Leo the Late Bloomer Kraus, Robert 27 0.5 1.2 5522 All By Myself (Little Critter) Mayer, Mercer 23 0.5 1.3 7202 Put me in the Zoo Lopshire, Robert 62 0.5 1.4 130449 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See Bill, Martin Jr. 28 0.5 1.5 40313 Green Eggs and Ham Suess, Dr. 72 0.5 1.5 9021 Hop on Pop Suess, Dr. 64 0.5 1.5 9023 Are You My Mother Eastman, P.D. 63 0.5 1.6 5456 Snow McKie, Roy 61 0.5 1.6 49420 Morris the Moose Wiseman, B. 32 0.5 1.6 65001 Sam and the Firefly Eastman, P.D. 62 0.5 1.7 47824 A Fish Out of Water Palmer, Helen 64 0.5 1.7 49392 One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish Suess, Dr. 63 0.5 1.7 9042 The Carrot Seed Krauss, Ruth 25 0.5 1.9 29233 A Fly Went By McClintock, Mike 62 0.5 1.9 122360 The Dot Reynolds, Peter H. 32 0.5 1.9 69954 LEVEL 2 Olivia Falconer, ian 32 0.5 2 44266 There's An Alligator Under My Bed Mayer, Mercer 29 0.5 2.1 34582 Big Max Platt, Kin 64 0.5 2.1 7307 Cat in the Hat Suess, Dr. -

Ð'ð¸Ð½ð³ Кñ€Ð¾ñби

Бинг КроÑÐ ±Ð¸ ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) High Society https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/high-society-3785538/songs 101 Gang Songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/101-gang-songs-20685801/songs The Happy Prince https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-happy-prince-23023176/songs Merry Christmas https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/merry-christmas-1762919/songs How the West Was Won https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/how-the-west-was-won-5918418/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/that-travelin%27-two-beat- That Travelin' Two-Beat 7711302/songs Selections from Irving Berlin's White https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/selections-from-irving-berlin%27s- Christmas white-christmas-17032045/songs Fancy Meeting You Here https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/fancy-meeting-you-here-5433697/songs Bing 'n' Basie https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/bing-%27n%27-basie-4914110/songs Bing & Satchmo https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/bing-%26-satchmo-16243926/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/on-the-sentimental-side- On the Sentimental Side 21161097/songs Seasons https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/seasons-7441927/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/bing-sings-whilst-bregman-swings- Bing Sings Whilst Bregman Swings 4914142/songs On the Happy Side https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/on-the-happy-side-20858181/songs Under Western Skies https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/under-western-skies-23020419/songs Songs I Wish I Had Sung the First Time https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/songs-i-wish-i-had-sung-the-first-time- Around around-7561341/songs St. -

The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860S-1940S

The Colonial Reinvention of the Hei Tiki: Pounamu, Knowledge and Empire, 1860s-1940s Kathryn Street A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington Te Whare Wānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a Māui 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the reinvention of pounamu hei tiki between the 1860s and 1940s. It asks how colonial culture was shaped by engagement with pounamu and its analogous forms greenstone, nephrite, bowenite and jade. The study begins with the exploitation of Ngāi Tahu’s pounamu resource during the West Coast gold rush and concludes with post-World War II measures to prohibit greenstone exports. It establishes that industrially mass-produced pounamu hei tiki were available in New Zealand by 1901 and in Britain by 1903. It sheds new light on the little-known German influence on the commercial greenstone industry. The research demonstrates how Māori leaders maintained a degree of authority in the new Pākehā-dominated industry through patron-client relationships where they exercised creative control. The history also tells a deeper story of the making of colonial culture. The transformation of the greenstone industry created a cultural legacy greater than just the tangible objects of trade. Intangible meanings are also part of the heritage. The acts of making, selling, wearing, admiring, gifting, describing and imagining pieces of greenstone pounamu were expressions of culture in practice. Everyday objects can tell some of these stories and provide accounts of relationships and ways of knowing the world. The pounamu hei tiki speaks to this history because more than merely stone, it is a cultural object and idea. -

When the Periphery Became More Central: from Colonial Pact to Liberal Nationalism in Brazil and Mexico, 1800-1914 Steven Topik

When the Periphery Became More Central: From Colonial Pact to Liberal Nationalism in Brazil and Mexico, 1800-1914 Steven Topik Introduction The Global Economic History Network has concentrated on examining the “Great Divergence” between Europe and Asia, but recognizes that the Americas also played a major role in the development of the world economy. Ken Pomeranz noted, as had Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Karl Marx before him, the role of the Americas in supplying the silver and gold that Europeans used to purchase Asian luxury goods.1 Smith wrote about the great importance of colonies2. Marx and Engels, writing almost a century later, noted: "The discovery of America, the rounding of the Cape, opened up fresh ground for the rising bourgeoisie. The East-Indian and Chinese markets, the colonisation of America [north and south] trade with the colonies, ... gave to commerce, to navigation, to industry, an impulse never before known. "3 Many students of the world economy date the beginning of the world economy from the European “discovery” or “encounter” of the “New World”) 4 1 Ken Pomeranz, The Great Divergence , Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000:264- 285) 2 Adam Smith in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776, rpt. Regnery Publishing, Washington DC, 1998) noted (p. 643) “The colony of a civilized nation which takes possession, either of a waste country or of one so thinly inhabited, that the natives easily give place to the new settlers, advances more rapidly to wealth and greatness than any other human society.” The Americas by supplying silver and “by opening a new and inexhaustible market to all the commodities of Europe, it gave occasion to new divisions of labour and improvements of art….The productive power of labour was improved.” p.