External Content.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oneg 6 – Toldos 2018

1 Oneg! A collection of fascinating material on the weekly parsha! Rabbi Elchanan Shoff Parshas TOLDOS Avraham begat Yitzchak (Gen. 25:19). The Or Hachaim and R. Shlomo Kluger (Chochmas Hatorah, Toldos p. 3) explain that it was in Avraham’s merit that G-d accepted Yitzchak’s prayers and granted him offspring. Rashi (to Gen. 15:15, 25:30) explains that G-d had Avraham die five years earlier than he otherwise should have in order that Avraham would not see Yitzchak’s son Esau stray from the proper path. I saw in the name of R. Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld (Chochmas Chaim to Toldos) that if Yitzchak had not campaigned vigorously in prayer to father a child, G-d would have granted him children anyways after five years. So in which merit did Yitzchak father his children, in Avraham’s merit or in the merit of his own prayers? Both are true: It was only in Avraham’s merit that Yitzchak deserved to father Yaakov and Esau, but the fact that the twins were born earlier rather than later came in merit of Yitzchak’s prayers. R. Sonnenfeld adds that the Torah’s expression equals in Gematria the (748 = ויעתר לו י-ה-ו-ה) that denotes G-d heeding Yitzchak’s prayers .The above sefer records that when a grandson of R .)748 = חמש שנים) phrase five years Sonnenfeld shared this Gematria with R. Aharon Kotler, he was so taken aback that he exclaimed, “I am certain that this Gematria was revealed through Ruach HaKodesh!” Yitzchak was forty years old when he took Rivkah—the daughter of Besuel the Aramite from Padan Aram, the sister of Laban the Aramite—as a wife (Gen. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

The American Rabbinic Career of Rabbi Gavriel Zev Margolis By

The American Rabbinic Career of Rabbi Gavriel Zev Margolis i: by Joshua Hoffman In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Modern Jewish History Sponsored by Dr. Jeffrey Gurock Bernard Revel Graduate School Yeshiva University July, 1992 [ rI'. I Table of Contents Introduction. .. .. • .. • . • .. • . .. .• 1 - 2 Chapter One: Rabbi Margolis' Background in Russia, 1847-1907•••••••.••.•••••••••••••.•••.•••.•••..•.• 3 - 18 Chapter Two: Rabbi Margolis' Years in Boston, 1907-1911........................................ 19 - 31 Chapter Three: Rabbi Margolis' Years in New York, 1911-1935••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••..••. 32 - 119 A. Challenging the Kehillah.. ... ..... ....... 32 - 48 B. Confronting the Shochtim and the Agudat Harabbonim.• .. •.. •.. •..•....••... ... .. 49 - 88 c. The Knesset Harabbonim... .... .... .... ... •. 89 - 121 Conclusions. ..................................... 122 - 125 Appendix . ........................................ 126 - 132 Notes....... .. .... .... ....... ... ... .... ..... .... 133 - 155 Bibliography .....•... •.•.... ..... .•.. .... ...... 156 - 159 l Introduction Rabbi Gavriel zev Margolis (1847-1935) is one of the more neglected figures in the study of American Orthodoxy in the early 1900' s. Although his name appears occasionally in studies of the period, he is generally mentioned only briefly, and assigned a minor role in events of the time. A proper understanding of this period, however, requires an extensive study of his American career, because his opposition -

Mothers of Soldiers in Israeli Literature David Grossman’S to the End of the Land

Mothers of Soldiers in Israeli Literature David Grossman’s To the End of the Land DANA OLMERT ABSTRACT This article addresses the national-political functions of mainstream Hebrew lit- erature, focusing on three questions: What are soldiers’ mothers in the canonical literature “allowed” to think, feel, and do, and what is considered transgressive? How has the presence of soldiers’ mothers in Israeli public life changed since the 1982 Lebanon War? At the center of the discussion is David Grossman’s novel To the End of the Land (2008). I argue that the author posits “the flight from bad tidings” as both a maternal strategy and the author’s psychopoetic strategy. This article examines the cultural and gendered significance of the analogy between the act of flight and the act of writing that Grossman advances in his epilogue. KEYWORDS mothers, soldiers, Hebrew literature, David Grossman srael’s 1982 war in Lebanon was the first to be perceived as a “war of choice” in I Israel, triggering a wave of protest as soon as units of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) crossed the border into Lebanon.1 Soldiers’ parents began to question the judgment of military leaders and to take a critical stance toward their sons’ military service. Although criticism of the militarization of Israeli society developed earlier during the 1970s and increased after the 1973 war, the 1982 war in Lebanon marked the first time that public criticism was expressed while fighting was going on. Pre- viously such criticism had emerged only after the end of hostilities.2 Only some years after the combatants’ mothers began speaking out about crucial national decisions did they become part of the literary fabric. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

A Zionist State at Any Cost

A Zionist State at Any Cost The foundation of Israel is tied up with David Ben-Gurion, its first prime minister. Through examining his life, we see how Israel’s creation was from its beginnings doomed to create an apartheid-like state maintained by an oppressor nation. Review essay of Tom Segev, A State at Any Cost. The Life of David Ben-Gurion, translated by Haim Watzman (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). David Ben-Gurion (1886–1973) was a key figure in the creation and building of the State of Israel, second in importance only to the founder of modern Zionism, Theodore Herzl, and central to the establishment of Zionism as the hegemonic politics and ideology of Jews everywhere. He was Israel’s first prime minister from its foundation in 1948 until he retired from political life in 1963 (with a brief hiatus from 1953 to 1955.)The Ben-Gurion that emerges from Tom Segev’s A State at Any Cost is a single-minded figure obsessively dedicated to the creation of the Jewish State in Palestine. He was not, Segev notes, a man of ideas interested in the development of Zionist theory, but a ruthless political and organization man willing to risk everything to accomplish his state-building goal. He pursued this even if it meant sacrificing the lives of Jews, let alone those of the Palestinians. Segev cites him telling members of his MAPAI party in the late thirties: “If I knew that it was possible to save all the [Jewish] children in Germany by transporting them to England, but only half by transporting them to Palestine, I would choose the second.” Richly and comprehensively portrayed by Tom Segev, one of the “new historians” challenging Israel’s founding myths, this new biography of David Ben-Gurion presents the history of Zionism and the shaping of the state of Israel through the life and times of its most important founder and political leader. -

Lions and Roses: an Interpretive History of Israeli-Iranian Relations" (2007)

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-13-2007 Lions and Roses: An Interpretive History of Israeli- Iranian Relations Marsha B. Cohen Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI08081510 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Cohen, Marsha B., "Lions and Roses: An Interpretive History of Israeli-Iranian Relations" (2007). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 5. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/5 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida LIONS AND ROSES: AN INTERPRETIVE HISTORY OF ISRAELI-IRANIAN RELATIONS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS by Marsha B. Cohen 2007 To: Interim Dean Mark Szuchman College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Marsha B. Cohen, and entitled Lions and Roses: An Interpretive History of Israeli-Iranian Relations, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ -

Torah Weekly

בס״ד Torah Defining Work One generations as an everlasting conventional understanding covenant. Between Me and is that we spend six days of Weekly of the most important the children of Israel, it is the week working and practices in Judaism, the forever a sign that [in] six pursuing our physical needs, February 28- March 6, 2021 fourth of the Ten 16-22 Adar, 5781 days the L-rd created the and on the seventh day we Commandments, is to heaven and the earth, and on rest from the pursuit of the First Torah: refrain from work on the Ki Tisa: Exodus 30:11 - 34:35 the seventh day He ceased physical and dedicate a day Second Torah: seventh day, to sanctify it and rested. (Exodus 31:16- to our family, our soul and Parshat Parah: Numbers 19:1-22 and make it holy. Yet, the 17.) our spiritual life. Yet the exact definition of rest and PARSHAT KI TISA From the juxtaposition of Torah is signaling to us that forms of labor prohibited Shabbat and the we should think about labor We have Jewish on Shabbat are not explicitly commandment to build the in the context of the work Calendars. If you stated in the Torah. necessary to construct the would like one, Tabernacle, we derive that The Sages of sanctuary. please send us a the Tabernacle may not be the Talmud explain that the constructed on Shabbat. This Thus, the halachic definition letter and we will Torah alludes to there being send you one, or implies that any labor that of “labor” is derived from 39 categories of prohibited ask the was needed for the the labor used for the Calendars labor. -

Wij-Articles-Revised Version of Outline of a Gender Conflict by Einat Baram

Outline of a Gender Conflict: Notes on an Early Story by Dvora Baron Outline of a Gender Conflict: Notes on an Early Story by Dvora Baron Einat Baram Eshel, Tel Aviv University, and Beit-Berl College, Israel Abstract This article examines Dvora Baron’s early story Zug mitkotet… (skitza) (A quarreling couple… [sketch]), about a young married couple drawn into a verbal and physical altercation. I propose that this early story already shows intimations of symbolism and complexity that characterize Baron’s later stories, as well as the first signs of the blurring and encoding of female protest that are characteristic of the second half of her work. Baron did this mainly by adapting the conventions of early twentieth-century male literature – private themes, short genres and fragmented language – and employing their meaning and purpose for female needs. Introduction Dvora Baron (1887-1956),1 a noted Russian-Israeli author, wrote over 80 short stories. She started writing during the Tkufat ha’thiya (Hebrew Renaissance Period) which occurred during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Her works have been highly analyzed in respect of the fact that she was one of a minority of women writers in a poetic world almost totally dominated by men. Baron’s works and life are generally considered to be divided into two major periods: early works (until the early 1920s, much of which Baron withheld from second publication) tending to focus on social themes and including somewhat blatant stories of women’s search for independence; and later works presenting the feminist angle more subtly, obscuring the feminist theme per se yet somewhat expanding it to include struggles of a more universal nature. -

A Taste of Torah

Lech Lecha 5776 October 23, 2015 This week’s edition is dedicated in memory of Avraham Moshe ben Yehuda Leib, Mr. Bud Glassman a”h, whose 8th yahrtzeit was Tuesday, 7 Cheshvan/October 20th A Taste of Torah Stories For The Soul Spare the Wealth A Cut Above By Rabbi Mordechai Fleisher For more than sixty years, Rabbi Avram has just miraculously defeated live” is a refernce to Avram’s fear that the Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld (1848-1932) served as a mohel. He never refused an four mighty kings. The reason for his going Egyptians would murder him to make his invitation to serve as mohel, and his to war in the first place? No, they weren’t wife available. But what is meant by “go face shone with joy when he had the trying to develop a nuclear weapon, well with me?” Rashi explains that Avram privilege of performing a bris milah on but they had just crushed the armies expected that the Egyptians would offer a Jewish child - “to add another Jew to of five other kings, and, in the process, him gifts to win his “sister’s” hand! How the King’s legions,” he would say. captured Avram’s nephew Lot. Avram felt does this jibe with the Avram who refuses responsible to rescue his nephew, and, with any recompense from the King of Sodom? Once, a huge snowstorm hit Jerusalem, leaving close to three feet of Divine intervention, he won a spectacular One approach to this conundrum may snow on the ground. Walking outside victory. be as follows: Rashi makes it clear that posed a real danger, especially for One of the five kings initially defeated when Avram went down to Egypt, he had someone of Rabbi Sonnenfeld’s age – before Avram appeared on the scene was a shortage of funds, and he incurred debts he was already in his 70’s. -

JO1993-V26-N01.Pdf

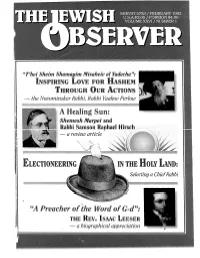

••• One of the best Astl wines tasted in a long while. AtllrurScb\VIJl'IZ NEW YORK DAILYN£WS •.• By larthe best was Bartenura Asti Spumante •• , In !act, it received the highest rating of any wine •.• s1 ..ley A. ll:det THE WASHINGTON POST .•• Outstanding from Italy is Bartenura's Asti Spumante, iu a delicate yet full· flavored mode •.. Nathan Chroman LOS ANGELES TIMES ... Bartenura Asti Spumante is among the best Asti Wines on the market. Rolwrt M. Porker, fr. THE WINE ADVOCATE I THEIEWISH . OBSERVER n I 1 l 1 THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021-66151 ' is published monthly except July and August by , I the Agudath Israel of America, 84 William Street, I New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage , paid in New York, N.Y. Subscription $22.00 per year; two years, $36.00; · three years, $48.00. Outside of the United States " (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $12.00 4 surcharge per year. Single copy $3.00; foreign "T'hei Sheim Shamayim Misaheiv al Yadecha": $4.00. Send address changes to: The Jewish Observer, 84 William Street, N.Y., N.Y. 10038. Inspiring Love for Hashem Through Our Actions Tel: (212) 797-9000. BASED ON ADDRESS BY THE NOVOM!NSKER REBBE, Printed in the U.S.A. RABBI YMKOV PERLOW N"1'Yro RABBI NISSON WOLPIN, EDITOR 9 EDITORIAL SOARD DR. ERNST L. BODENHEIMER Agudath Israel of America's Statement Chalrmrm re: New NYS Get Law RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS JOSEPH FRIEDENSON RABBI NOSSON SCHERMAN 10 Electioneering in the Holy Land: MANAGEMENT BOARD AVI FISHOF Selecting a Chief Rabbi NAFTOLI HIRSCH Rabbi Yonason Rosenblum ISAAC KIAZNER RABBI SHLOMO LESIN NACHUM STEIN 17 RABBI YOSEF C. -

University of London Thesis

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year Name of Author C£VJ*r’Nr^'f ^ COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D.