Capital Spaces Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karori Water Supply Dams and Reservoirs Register Report

IPENZ Engineering Heritage Register Report Karori Water Supply Dams and Reservoirs Written by: Karen Astwood and Georgina Fell Date: 12 September 2012 Aerial view of Karori Reservoir, Wellington, 10 February 1985. Dominion Post (Newspaper): Photographic negatives and prints of the Evening Post and Dominion newspapers, Alexander Turnbull Library (ATL), Wellington, New Zealand, ID: EP/1984/0621. The Lower Karori Dam and Reservoir is in the foreground and the Upper Karori Dam and Reservoir is towards the top of the image. 1 Contents A. General information ........................................................................................................... 3 B. Description ......................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Historical narrative .................................................................................................................... 6 Social narrative ...................................................................................................................... 10 Physical narrative ................................................................................................................... 18 C. Assessment of significance ............................................................................................. 24 D. Supporting information ..................................................................................................... -

Modeling Site Effects in the Lower Hutt Valley, New Zealand

2694 MODELING SITE EFFECTS IN THE LOWER HUTT VALLEY, NEW ZEALAND Brian M ADAMS1, John B BERRILL2, Rob O DAVIS3 And John J TABER4 SUMMARY Lower Hutt City lies atop a wedge of Quaternary sediments forming a long alluvial valley. On its western edge the sediments butt up against the near vertical wall of the potentially active Wellington Fault, capable of an earthquake of moment magnitude 7.6. A two-dimensional linear finite-element method has been used to model the propagation of antiplane SH waves within the soft sediments and surrounding bedrock. The technique has proved to be an efficient and accurate means of modeling fine geological detail. Two detailed geological cross-sections through the Lower Hutt were modeled to gain an overall impression of the valley's seismic behaviour. It was found that horizontally propagating surface waves, generated at the valley edges, are the cause of significant amplification. The aptly named basin-edge effect – speculated to be the cause of a belt of severe shaking during the 1995 Kobe earthquake – is observed in the simulation results, occuring some 70-200 metres out from the fault. Fourier spectral ratios across the valley indicate a behaviour dominated by two-dimensional resonance, and compare favourably in magnitude with previously collected weak motion data. Certain resonant frequencies within the range 0.3-2.5 hertz are amplified up to 14 times that for nearby outcropping bedrock. Results are likely to be conservative due to the linear modeling, yet exclude fault-rupture effects due to the teleseismic nature of the input scheme. INTRODUCTION In this paper we describe our use of a two-dimensional finite-element numerical scheme to simulate ground motions from earthquake shaking in the soft sediments in-filling the Lower Hutt Valley. -

Wellington Harbour Sub-Region

Air, land and water in the Wellington region – state and trends Wellington Harbour sub-region This is a summary of the key findings from State of the Environment Key points monitoring we carry out in the Wellington Harbour and south coast • Air quality is very good overall, except catchments. It is one of five sub-region summaries of eight technical during winter in some residential areas reports which give the full picture of the health of the Wellington on cold and calm evenings – when fine region’s air, land and water resources. These reports are produced particles produced by woodburners don’t every five years. disperse The findings are being fed into the current review of Greater • The quality of the groundwater is very Wellington’s regional plans – the ‘rule books’ for ensuring our high region’s natural resources are sustainably managed. • Most of the freshwater used in the sub- region goes to public water supply – You can find out how to have a say in our regional plan review on there’s very little water left to allocate from the back page. the major rivers or groundwater aquifers Key features • River and stream health is excellent at sites This sub-region is home to most of the people living in the Wellington near the ranges but is degraded further region – although it only makes up 14% of the region’s land area downstream, especially in urban areas (1,183km2). It covers Wellington, Upper Hutt and Hutt cities, and also • Most beach and river recreation sites we the Wainuiomata Valley and Wellington’s south coast. -

60E Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

60E bus time schedule & line map 60E Porirua - Tawa - Johnsonville - Wellington View In Website Mode The 60E bus line (Porirua - Tawa - Johnsonville - Wellington) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua Station - Stop B: 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM (2) Courtenay Place - Stop A →Whitireia Polytechnic - Titahi Bay Road: 7:33 AM - 7:52 AM (3) Porirua Station - Stop B →Courtenay Place - Stop C: 6:25 AM - 7:45 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 60E bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 60E bus arriving. Direction: Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua 60E bus Time Schedule Station - Stop B Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua Station - Stop B 49 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Courtenay Place - Stop A 25 Courtenay Place, New Zealand Tuesday Not Operational Courtenay Place at St James Theatre Wednesday 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM 77 Courtenay Place, New Zealand Thursday 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM Manners Street at Cuba Street - Stop A Friday 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM 106 Manners Street, New Zealand Saturday Not Operational Manners Street at Willis Street 2 Manners Street, New Zealand Willis Street at Grand Arcade 12 Willis Street, New Zealand 60E bus Info Direction: Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua Station Lambton Quay at Cable Car Lane - Stop B 256 Lambton Quay, New Zealand Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 56 min Lambton Central - Stop A Line Summary: Courtenay Place - Stop A, Courtenay 204 Lambton Quay, New Zealand Place at St James Theatre, Manners Street -

Wellington Walks – Ara Rēhia O Pōneke Is Your Guide to Some of the Short Walks, Loop Walks and Walkways in Our City

Detail map: Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori Hill) Detail map: Mount Victoria (Matairangi) Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. ade North North Wellington Otari-Wilton’ss BushBush OrientalOriental ParadePar W ADESTOWN WeldWeld Street Street Wade Street Oriental Bay Walks Grass St. WILTON Oriental Parade O RIEN T A L B A Y Ara Rēhia o Pōneke Northern Walkway PalliserPalliser Rd.Rd. Skyline Walkway To City ROSENEATH Majoribanks Street City to Sea Walkway LookoutLookout Rd.Rd. Te Ara o Ngā Tūpuna Mount Victoria Lookout MOUNT (Tangi(Tangi TeTe Keo)Keo) Te Ahumairangi Hill GrantGrant RoadRoad VICT ORIA Lookout PoplarPoplar GGroroveve PiriePirie St.St. THORNDON AlexandraAlexandra RoadRoad Hobbit Hideaway The Beehive Film Location TinakoriTinakori RoadRoad & ParliameParliamentnt rangi Kaupapa RoadStSt Mary’sMary’s StreetStreet OOrangi Kaupapa Road buildingsbuildings WaitoaWaitoa Rd.Rd. HataitaiHataitai RoadHRoadATAITAI Welellingtonlington BotanicBotanic GardenGarden A B Southern Walkway Loop walks City to Sea Walkway Matairangi Nature Trail Lookout Walkway Northern Walkway Other tracks Southern Walkway Hataitai to City Walkway 00 130130 260260 520520 Te Ahumairangi metresmetres Be prepared For more information Your safety is your responsibility. Before you go, Find our handy webmap to navigate on your mobile at remember these five simple rules: wcc.govt.nz/trailmaps. This map is available in English and Te Reo Māori. 1. Plan your trip. Our tracks are clearly marked but it’s a good idea to check our website for maps and track details. Find detailed track descriptions, maps and the Welly Walks app at wcc.govt.nz/walks 2. Tell someone where you’re going. -

Stormwater Infrastructure

Assessment of Water and Sanitary Services 2005 x Long Term Council Community Plan x Bush and Stream Restoration Plan 2001 x Asset Management Plan. 6.3 Stormwater Infrastructure 6.3.1 Catchments A catchment is defined by topography. A main stream and tributaries join together in the catchment to form a water system which drains through a single outlet into the harbour or south coast. Council catchments are generally based upon actual drainage characteristics, but are also affected by management boundaries. The more urbanised eastern side of the Wellington region has been broken up into 42 individual catchments ranging in size and elevation from rural Kaiwharawhara (1917 ha, 420m) to smaller urban catchments such as Thorndon (12 ha, sea level). The rural western region has not been subdivided into catchments at this time. Figure 9 shows the main stormwater catchments. All these catchments contain a multitude of small watercourses, streams and piped stormwater infrastructure. The rural streams are generally narrow and restricted channels with over hanging vegetation, compared to the channelised urban streams. Streams have an average grade of 7.25% throughout the region, representing the steep topography associated with most of the Wellington catchments. Wellington stormwater from these catchments is discharged directly into the City’s streams, harbour and south coast. Eleven of the major discharges to the sea are currently consented under the RMA 1991. The consents for the discharge of wastewater-contaminated stormwater to the coastal marine area were issued in 1994 and require Council to carry out improvement works by 2013. The works are dependent on the individual consent conditions. -

Hydrodynamic Inundation Modelling for Wellington Harbour, 2015

DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office and the Greater Wellington Regional Council. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of, or reliance on any contents of this Report by any person other than the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office and the Greater Wellington Regional Council and shall not be liable to any person other than the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office and the Greater Wellington Regional Council, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. Use of Data: Date that GNS Science can use associated data: October 2015 Wellington Harbour Bathymetry disclaimer: This report publishes results that are reliant on the 1m grid Wellington Harbour Bathymetric data set (‘the Data’) provided by the National Institute for Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA). GNS Science and NIWA make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or completeness of ‘the Data’ the use to which ‘the Data’ has been put in this report, or the results in this report which have been obtained from using the Data. GNS Science and NIWA accept no liability for any loss or damage (whether direct or indirect) incurred by any person through the use of or reliance on ‘the Data’ or use or reliance on the results in this report which have been obtained from using the Data. BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Mueller, C.; Power, W.L.; Wang, X. 2015. -

Golden Mile Engagement Report June

GOLDEN MILE Engagement summary report June – August 2020 Executive Summary Across the three concepts, the level of change could be relatively small or could completely transform the road and footpath space. The Golden Mile, running along Lambton Quay, Willis Street, Manners Street and 1. “Streamline” takes some general traffic off the Golden Mile to help Courtenay Place, is Wellington’s prime employment, shopping and entertainment make buses more reliable and creates new space for pedestrians. destination. 2. “Prioritise” goes further by removing all general traffic and allocating extra space for bus lanes and pedestrians. It is the city’s busiest pedestrian area and is the main bus corridor; with most of the 3. “Transform” changes the road layout to increase pedestrian space city’s core bus routes passing along all or part of the Golden Mile everyday. Over the (75% more), new bus lanes and, in some places, dedicated areas for people next 30 years the population is forecast to grow by 15% and demand for travel to and on bikes and scooters. from the city centre by public transport is expected to grow by between 35% and 50%. What we asked The Golden Mile Project From June to August 2020 we asked Wellingtonians to let us know what that they liked or didn’t like about each concept and why. We also asked people to tell us The Golden Mile project is part of the Let’s Get Wellington Moving programme. The which concept they preferred for the different sections of the Golden Mile, as we vision for the project is “connecting people across the central city with a reliable understand that each street that makes up the Golden Mile is different, and a public transport system that is in balance with an attractive pedestrian environment”. -

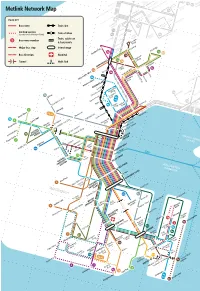

Metlink Network

1 A B 2 KAP IS Otaki Beach LA IT 70 N I D C Otaki Town 3 Waikanae Beach 77 Waikanae Golf Course Kennedy PNL Park Palmerston North A North Beach Shannon Waikanae Pool 1 Levin Woodlands D Manly Street Kena Kena Parklands Otaki Railway 71 7 7 7 5 Waitohu School ,7 72 Kotuku Park 7 Te Horo Paraparaumu Beach Peka Peka Freemans Road Paraparaumu College B 7 1 Golf Road 73 Mazengarb Road Raumati WAIKANAE Beach Kapiti E 7 2 Arawhata Village Road 2 C 74 MA Raumati Coastlands Kapiti Health 70 IS Otaki Beach LA N South Kapiti Centre A N College Kapiti Coast D Otaki Town PARAPARAUMU KAP IS I Metlink Network Map PPL LA TI Palmerston North N PNL D D Shannon F 77 Waikanae Beach Waikanae Golf Course Levin YOUR KEY Waitohu School Kennedy Paekakariki Park Waikanae Pool Otaki Railway ro 3 Woodlands Te Ho Freemans Road Bus route Parklands E 69 77 Muri North Beach 75 Titahi Bay ,77 Limited service Pikarere Street 68 Peka Peka (less than hourly, Monday to Friday) Titahi Bay Beach Pukerua Bay Kena Kena Titahi Bay Shops G Kotuku Park Gloaming Hill PPL Bus route number Manly Street71 72 WAIKANAE Paraparaumu College 7 Takapuwahia 1 Plimmerton Paraparaumu Major bus stop Train line Porirua Beach Mazengarb Road F 60 Golf Road Elsdon Mana Bus direction 73 Train station PAREMATA Arawhata Mega Centre Raumati Kapiti Road Beach 72 Kapiti Health 8 Village Train, cable car 6 8 Centre Tunnel 6 Kapiti Coast Porirua City Cultural Centre 9 6 5 6 7 & ferry route 6 H Coastlands Interchange Porirua City Centre 74 G Kapiti Police Raumati College PARAPARAUMU College Papakowhai South -

Western Corridor Plan Adopted August 2012 Western Corridor Plan 2012 Adopted August 2012

Western Corridor Plan Adopted August 2012 Western Corridor Plan 2012 Adopted August 2012 For more information, contact: Greater Wellington Published September 2012 142 Wakefield Street GW/CP-G-12/226 PO Box 11646 Manners Street [email protected] Wellington 6142 www.gw.govt.nz T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 Western Corridor Plan Strategic Context Corridor plans organise a multi-modal response across a range of responsible agencies to the meet pressures and issues facing the region’s land transport corridors over the next 10 years and beyond. The Western Corridor generally follows State Highway 1 from the regional border north of Ōtaki to Ngauranga and the North Island Main Trunk railway to Kaiwharawhara. The main east- west connections are State Highway 58 and the interchange for State Highways 1 and 2 at Ngauranga. Long-term vision This Corridor Plan has been developed to support and contribute to the Regional Land Transport Strategy (RLTS), which sets the objectives and desired outcomes for the region’s transport network. The long term vision in the RLTS for the Western Corridor is: Along the Western Corridor from Ngauranga to Traffic congestion on State Highway 1 will be Ōtaki, State Highway 1 and the North Island Main managed at levels that balance the need for access Trunk railway line will provide a high level of access against the ability to fully provide for peak demands and reliability for passengers and freight travelling due to community impacts and cost constraints. within and through the region in a way which Maximum use of the existing network will be achieved recognises the important strategic regional and by removal of key bottlenecks on the road and rail national role of this corridor. -

Wellington Harbour Ferry

Effective from 15 July 2018 Wellington Harbour Ferry Queens Wharf Matiu / Somes Island Wharf Seatoun Wharf Thanks for travelling with Metlink. Days Bay Wharf Connect with Metlink for timetables and information about bus, train and ferry services in the Wellington region. metlink.org.nz 0800 801 700 [email protected] Printed with mineral-oil-free, soy-based vegetable inks on paper produced using Forestry Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified mixed-source pulp that complies with environmentally responsible practices and principles. Please recycle and reuse if possible. Before taking a printed timetable, check our timetables online or use the Metlink commuter app. GW/PT-G-18/92 July 2018 July GW/PT-G-18/92 TO DAYS BAY WHARF MONDAY TO FRIDAY FARES FARE INFORMATION Stops AM PM 9997 Queens Wharf 6:20 6:45 7:15 7:40 8:20 8:55 10:00 12:00 2:05 3:30 4:30 5:00 5:30 5:55 6:30 7:05 Child fares: 9995 Seatoun Wharf 4:00 6:15 ONE WAY TICKET Adult Child – are half the adult fares for the equivalent journeys Matiu / Somes Island 10:25 12:25 2:30 9998 Queens Wharf - Days Bay $12.00 $6.00 on ferry sailings 9999 Days Bay Wharf 6:45 7:10 7:40 8:05 8:45 9:20 10:40 12:40 2:45 4:25 4:55 5:25 5:55 6:40 6:55 7:30 Days Bay - Seatoun $12.00 $6.00 – apply to all school children SI SI SI Queens Wharf - Seatoun $12.00 $6.00 – secondary school students must be in school uniform or present valid school photo ID, RETURN TICKET Adult Child if requested TO QUEENS WHARF – passengers entitled to the Accessible Concession MONDAY TO FRIDAY Queens Wharf - Days Bay $24.00 $12.00 -

Distribution of Geological Materials in Lower Hutt and Porirua, New Zealand a Component of a Ground Shaking Hazard Assessment

332 DISTRIBUTION OF GEOLOGICAL MATERIALS IN LOWER HUTT AND PORIRUA, NEW ZEALAND A COMPONENT OF A GROUND SHAKING HAZARD ASSESSMENT G. D. Dellow1 , S. A. L. Read 1 , J. G. Begg1 , R. J. Van Dissen1 , N. D. Perrin1 ABSTRACT Geological materials in the Lower Hutt, Eastbourne, Wainuiomata, and Porirua urban areas are mapped and described as part of a multi-disciplinary assessment of seismic ground shaking hazards. Emphasis is mainly on the flat-lying parts of these areas which are underlain by variable Quaternary-age sediments that overlie Permian-Mesowic age 'greywacke' bedrock. Within the Quaternary-age sediments, the two material types recognised on strength characteristics are: 1) Soft sediments, typically composed of normally consolidated, fine-grained materials (sand, silt and clay), with typical standard penetration values (SPT) of <20 blows/300 mm; and 2) Loose to compact coarser-grained materials (sand, gravel), with SPT values of > 20 blows/ 300 mm. The total thickness and nature of Quaternary-age sediments in the study areas is described, with particular emphasis on the thickness and geotechnical properties of near-surface sediments. Such sediments are considered likely to have a significant influence on the an1plification and attenuation of ground shaking intensity during earthquakes. In the Lower Hutt valley, near-surface soft sediments greater than 10 m thick have an areal extent of -16 kni. Such soft sediments underlie much of Petone and the Lower Hutt urban and city centres, and have a maximum known thickness of 27 m near the western end of the Petone foreshore. In the Wainuiomata area, near-surface soft sediments greater than 10 m thick have an areal extent of - 3 krn2, and attain a maximum thickness of 32 m.