Zozie, Paxton A.M. (2020) Integrating E-Learning Technologies Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tracer Study of ICT Graduate Students at Mzuzu University, Malawi

Article A Tracer Study of ICT Graduate Students at Mzuzu University, Malawi Chimango Nyasulu Winner Chawinga https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8838-2848 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3865-4777 Mzuzu University, Malawi Mzuzu University, Malawi [email protected] [email protected] George Chipeta https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8116-8195 Mzuzu University, Malawi [email protected] Abstract Governments the world over are increasingly challenging universities to produce human resources with the right skill sets and knowledge required to drive their economies in the twenty-first century. It therefore becomes important for universities to produce graduates that bring tangible and meaningful contributions to the economies. Graduate tracer studies are hailed to be one of the ways in which universities can respond and reposition themselves to the actual needs of the industry. It is against this background that this study was conducted to establish the relevance of the Department of Information and Communication Technology at Mzuzu University to the Malawian economy by systematically investigating occupations of its former students after graduating from the University. The study adopted a quantitative design by distributing an online-based questionnaire with predominantly closed-ended questions. The study focused on three key objectives: to identify key employing sectors of ICT graduates, to gauge the relevance of the ICT programme to its former students’ jobs and businesses, and to establish the level of satisfaction of the ICT curriculum from the perspectives of former ICT graduates. The key findings from the study are that the ICT programme is relevant to the industry. However, some respondents were of the view that the curriculum should be strengthened by revising it through an addition of courses such as Mobile Application Development, Machine Learning, Natural Language Processing, Data Mining, and LINUX Administration to keep abreast with the ever-changing ICT trends and job requirements. -

Why Do Postgraduate Students Commit Plagiarism? an Empirical Study Apatsa Selemani1* , Winner Dominic Chawinga2 and Gift Dube3

Selemani et al. International Journal for Educational Integrity (2018) 14:7 International Journal for https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0029-6 Educational Integrity ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Why do postgraduate students commit plagiarism? An empirical study Apatsa Selemani1* , Winner Dominic Chawinga2 and Gift Dube3 * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 1 College of Medicine Library, ’ University of Malawi, Blantyre, The study investigated postgraduate students knowledge of plagiarism, forms of Malawi plagiarism they commit, the reasons they commit plagiarism and actions taken Full list of author information is against postgraduate students who plagiarise at Mzuzu University in Malawi. The available at the end of the article study adopted a mixed methods approach. The quantitative data were collected by distributing questionnaires to postgraduate students and academic staff whereas qualitative data were collected by conducting follow-up interviews with some academics, an assistant registrar and assistant librarian. The study found that despite students reporting that they had a conceptual understanding of plagiarism, the majority of them reported that they had intentionally and unintentionally committed plagiarism, mainly due to pressure for good grades (86.7%), laziness and poor time management (84.9%), and lack of good academic writing skills (84.9%). The study also established that prevalent forms of plagiarism admitted (by students) and reported (by academic staff) to have been committed included lack of proper acknowledgement after paraphrasing (69.8%), summarising (64.1%) and using quotation marks (56.6%). The study further found that the common sanctions applied by academics include giving a warning and asking the student to re-write the plagiarised work. -

Improving Higher Education in Malawi for Competitiveness in the Global

A WORLD BANK STUDY Improving Higher Education in Malawi for Competitiveness the Global Economy he government of Malawi is currently investigating options to expand access to higher T education and improve its quality. The objective of Improving Higher Education in Malawi for Competitiveness in the Global Economy is to contribute to an improved understanding of the challenges confronted by the higher education subsector in Malawi. The report summarizes the key fi ndings of an in-depth study of factors affecting access and equity in the Malawian higher education subsector, the quality and relevance of educational outputs, the fi nancing of the sector, and the frameworks structuring governance of the sector and its management. The study was initiated by the World Bank in response to a request from the government of Malawi to support the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST) in its pursuit of fi nancially sustainable policy options to increase equitable access to higher education and to improve the quality of higher education provision in alignment with the needs of the labor market. Improving Higher Education in Malawi for Competitiveness in the Global Economy ISBN 978-1-4648-0798-5 Michael M. Mambo, Muna Salih Meky, Nobuyuki Tanaka and Jamil Salmi SKU 210798 Improving Higher Education in Malawi for Competitiveness in the Global Economy A WORLD BANK STUDY Improving Higher Education in Malawi for Competitiveness in the Global Economy Michael M. Mambo, Muna Salih Meky, Nobuyuki Tanaka and Jamil Salmi © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 World Bank Studies are published to communicate the results of the Bank’s work to the development com- munity with the least possible delay. -

Collaboration That Works: Public Universities Learn to Share

Collaboration that works: Public universities learn to share Dr Mhango (left) sharing knowledge across all five public universities and (right), participants from Chancellor College With schools indefinitely closed due to COVID-19, the soft underbelly of Malawi’s education system has been exposed and calls to invest more in Open Distance and e-Learning (ODeL) could never be any louder. With limited resources to fast-track the provision of ODeL among the country’s higher learning institutions, collaboration is the obvious way to go. Unfortunately, higher learning institutions are not too popular with sharing resources as they regard each other competitors – but not anymore. Thanks to the USAID-funded SHEAMA project, four public universities in Malawi can now work together, sharing knowledge and material resources in a bid to upscale delivery of lessons through ODeL as a response to COVID-19. What started last year with the signing of a MOU among the institutions – Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (LUANAR), Mzuzu University, Chancellor College, Polytechnic and Malawi University of Science and Technology (MUST), has blossomed into the actual sharing of resources to achieve the common goal of increasing access to higher education. Among other things, the five colleges have opened up their satellite centers to the rest of the group. This means any of the colleges has access to a satellite center owned by any of the member colleges for delivery of lessons through ODeL in a cost-effective manner. What a winner for Malawi’s underserved students! SHEAMA facilitated the development of an ODL center business model which ensures that the facilities are utilized amongst the colleges in a sustainable manner. -

Malawi Nursing Education Partnership Initiative

Malawi Nursing Education Partnership Initiative Background About: NEPI is addressing critical shortages In rural Malawi, nurses and midwives account for over 90 percent of health care of health care workers in six sub-Saharan providers. An acute shortage of health care workers coupled with a high disease burden, African countries: Democratic Republic of however, is placing considerable strain on the existing workforce. In Malawi, where the Congo, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Malawi, the HIV prevalence rate is over 11 percent, sufficient numbers of adequately trained South Africa, and Zambia. nurses are needed to address essential population-based health care needs, including antiretroviral treatment for HIV. Key Health Challenges In 2011, ICAP launched the Nursing Education Partnership Initiative (NEPI) with support from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through U.S. Health Health Care Worker Density in Malawi Resource and Service Administration (HRSA) to improve the quantity and quality of the nursing and midwifery workforce. Through NEPI, ICAP is working in partnership with Malawi’s Ministry of Health (MOH) to enhance nursing and midwifery education at four 230 institutions: • Kamuzu College of Nursing at the University of Malawi • WHO- • Malawi College of Health Sciences recommended • Mzuzu University HCWs per • Nurses and Midwives Council of Malawi • Malawi 32 100,000 people In Malawi, NEPI is addressing the following challenges to nursing and midwifery education: 1) limited number of tutors and clinical preceptors 2) limited capacity to meet the needs of an increased number of students 3) under-resourced teaching and learning Leading Causes of Death in Malawi facilities; and 4) limited opportunities for advanced study and career development. -

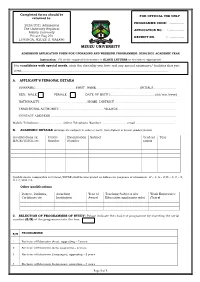

2020 2021 Admission Form

Completed forms should be FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY returned to: PROGRAMME CODE: …………… 2020/2021 Admissions The University Registrar APPLICATION NO. : …………… Mzuzu University Private Bag 201 RECEIPT NO. : …..……… LUWINGA, MZUZU 2, MALAWI MZUZU UNIVERSITY ADMISSION APPLICATION FORM FOR UPGRADING AND WEEKEND PROGRAMMES: 2020/2021 ACADEMIC YEAR Instruction: Fill in the required information in BLOCK LETTERS or tick where appropriate For candidates with special needs, state the disability you have and any special assistance/ facilities that you need:…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….............. A. APPLICANT’S PERSONAL DETAILS ______________________________________________ SURNAME:………………………………… FIRST NAME………………..…………..……… INITIALS………………….. SEX: MALE FEMALE DATE OF BIRTH………………………………………(dd/mm/yyyy) NATIONALITY……………………………………….. HOME DISTRICT …………………………………………………… TRADITIONAL AUTHORITY………………………………………VILLAGE…………………………………………………. CONTACT ADDRESS ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Mobile Telephone ……………………Other Telephone Number……….…………… email ………………………………… B. ACADEMIC DETAILS (arrange the subjects in order of merit; from highest to lowest grades/points) Qualifications eg: Centre Examination Subject Grades/ Year MSCE/IGSCE etc. Number Number points Qualifications comparable to O-Level/IGCSE shall be interpreted as follows for purposes of admission: A*= 1; A = 2; B = 3; C = 5; D = 7; EFG = 8. Other qualifications Degree, Diploma, Awarding Year of Teaching Subjects (for Work Experience Certificate etc Institution Award Education applicants -

National Workshop on Instructional Design

Instructional Design Workshop Sponsored by Mzuzu University and The Commonwealth of Learning Mzuzu, Malawi June 22-26, 2009 ________________________________________________ Project Manager: Dr. Asha Kanwar Vice President and Programme Director The Commonwealth of Learning Vancouver, Canada Programme Coordinator: Lydia Meister The Commonwealth of Learning Vancouver, Canada Local Organizer: Dr. Fred Msiska Director Centre for Open and Distance Learning Mzuzu University Mzuzu, Malawi Event Facilitator Clayton R. Wright, PhD and Report Writer: Higher Education Consultant Edmonton, Canada Contents Purpose 2 Participants 3 Workshop Activities 4 Workshop Outcomes 11 Recommendations 12 Appendix: Participants’ Comments Provided on the Evaluation Form 14 Purpose According to the Commonwealth of Learning, the purpose of the workshop was to help Mzuzu University academic staff “gain an understanding and insight into how to design and develop instructional materials” for an open and distance learning setting. Specifically, the workshop was mounted to: • expose Mzuzu University academic staff to the theory of designing and developing open and distance learning materials; • offer the academic staff an opportunity to practice designing and developing open and distance learning materials; and • enable participants to produce at least one unit of open and distance learning materials by the end of the workshop. The workshop facilitator informed the Commonwealth of Learning that the latter objective would be difficult to accomplish within the timeframe provided. The facilitator could guide the participants as they developed the material, but the participants must be able and willing to work during the evenings to draft the learning material. The responsibility for completing the units lies with the participants, not the facilitator. The expected outputs of the training workshop were: • a folder of guide notes and illustrations for developing open and distance learning materials; • a blueprint of a unit of learning material; and • one complete draft unit based on the blueprint. -

Experiences from Mzuzu University, Malawi

Thriving on the power of a record: experiences from Mzuzu University, Malawi by Winner Chawinga1 Lecturer, Department of Library and Information Science, Mzuzu University, Malawi Gift Dube2 Children’s and Outreach Services Librarian and Part-time Lecturer in the Department of Library and Information Science, Mzuzu University, Malawi, Allan Kanyundo3 Technical Services Librarian and Part-time Lecturer in Library and Information Science, Mzuzu University, Malawi Hamis Abdullah4 Senior Library Assistant and Part-time Assistant Lecturer in Library and Information Science, Mzuzu University, Malawi. Abstract Most organisations, whether publicly or privately owned produce records in the course of transacting their daily businesses. Such records need to be properly managed and preserved for various reasons. For example, it is common knowledge that proper keeping of records helps the organisation to avoid unnecessary law suits that may results from misplacement of important records. Mzuzu University, like other public universities in Malawi, generates numerous records which are critical to its existence and proper functionality. However, much as Mzuzu University has a registry (where a sizable amount of records are officially kept), there is an official proposal by Mzuzu University Management to establish a record centre. This paper reports on the findings about how Mzuzu University is managing its vital records. A mixed method approach is applied in this study. First, conducted interviews with the University Registrar and secondly, we sent a questionnaire to staff working in the university registry and five deans of faculties at Mzuzu University. The study reports in various benefits of proper records management and it also identifies key challenges affecting the proper management of records at Mzuzu University. -

Information Behaviour of Final Year Students of Mzuzu University in Malawi

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Spring 4-27-2015 Information behaviour of final year students of Mzuzu University in Malawi. Maloto G. Chaura Mr. Mzuzu University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Chaura, Maloto G. Mr., "Information behaviour of final year students of Mzuzu University in Malawi." (2015). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1249. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1249 Information behaviour of final year students of Mzuzu University in Malawi. Abstract. This paper presents findings for a research study which investigated the information behaviour of final students of Mzuzu University in Malawi. Even after being imparted with necessary skills in how to search and locate relevant information, the author observed that students still find difficulties to find information that they require. A paper based questionnaire was designed and administered to two hundred and fifty four (254) final year students belonging to the five faculties of the University of which two hundred and forty three (243) responded to the questionnaire A mixed method questionnaire survey was used. Stratified sampling in which students were divided into different strata according to the faculty they belong to was adopted. The Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process model was used as a guiding theoretical framework for this study. The results show that most of the students relied heavily on the Internet (64.6%), search engines like Google (56.2%) and the OPAC (45%). -

1 the Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM)

Title Enhancing capacity building for reproductive knowledge and product marketing for Adansonia digitata L to improve rural livelihoods in Malawi PI Associate Professor Chimuleke Rowland Yagontha Munthali (PhD) Mzuzu University, Private Bag 201, Luwinga, Mzuzu 2. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Tel: Office +265 1320081; mobile +265 888304113 Co-Researchers Dr. Chanyenga Tembo Forestry Research Institute of Malawi Email: [email protected], Tel: +265999871195 or +2651524548 Dr Mavuto Tembo Mzuzu University Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Land Management department Email: [email protected], Tel: +265997376822 Mr Leonard manda Mzuzu university, Faculty of education, Department of Biological Sciences Email: [email protected], Tel: +265884713714 Associate Professor Victor Kasulo Director of Research Mzuzu University Email: [email protected], Tel: +265888343494 Dr. Wales Singini Faculty of Environmental Sciences Fisheries department, Mzuzu University Email: [email protected] Tel: +265888340793 Mr Joel Luhanga Forestry Department Faculty of Environmental Sciences 1 The Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM) Mzuzu University Email: [email protected] Tel: +265999652725 Mrs Jarret Mhango Forestry Department Faculty of Environmental Sciences Mzuzu University Email: [email protected] Tel: +265999374389 Mr Victor Msiska Forestry Department Faculty of Environmental Sciences Mzuzu University Email: [email protected] Tel: +265999185950 Purpose The purpose of the study will be to generate knowledge on the contribution of the baobab tree to the livelihoods of rural communities, through understanding its value chain and reproductive biology that could help in its domestication, improvement and management in order to sustain tree productivity in agroforestry systems. Project Adansonia digitata L (Baobab) is indigenous in the drier areas of summary Africa occurring in about 26 countries. -

The Use of Electronic Journal Articles by Academics at Mzuzu University, Malawi

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 4-2-2014 The seU of Electronic Journal Articles by Academics at Mzuzu University, Malawi. Lizzie Malemia Mzuzu University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Malemia, Lizzie, "The sU e of Electronic Journal Articles by Academics at Mzuzu University, Malawi." (2014). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1097. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1097 THE USE OF ELECTRONIC JOURNAL ARTICLES BY ACADEMICS AT MZUZU UNIVERSITY, MALAWI. Lizzie Malemia Mzuzu University Library Private Bag 201 Luwinga, Mzuzu 2 Malawi. Email: [email protected] Abstract The use of information technology for scholarly publication is now commonplace all over the world. Academic communities in Africa are part of this transformation. The purpose of this study was to investigate academics’ use of scholarly electronic journal articles at Mzuzu University and assess the factors influencing their behaviour. Data collection instruments used for the study were the use of a questionnaire to the academics, interview with Deans of Faculties and follow up e-survey to some academics at Mzuzu University. The findings revealed that most academics had general knowledge of the electronic journals and this did not vary with education. There was no significant difference between gender and searching skills. It was evident that majority of academics prefer local publications and the use of electronic journal articles was for teaching and research. However, there were some barriers including teaching responsibilities; a lack of ICT and telecommunications; unreliable power supply; access to journals was restricted to campus and a lack of local content. -

National Council for Higher Education Press Release

Edited by C. Fletcher (Aug 10, 201ly 28, 2011) NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR HIGHER EDUCATION PRESS RELEASE REGISTERED AND ACCREDITED HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS IN MALAWI The National Council for Higher Education Act (No. 15 of 2011) gives mandate to the Council to regulate higher education institutions in Malawi. In line with this mandate, the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) wishes to notify the general public that as at 31st July 2019 the list of registered and accredited institutions in Malawi is as follows: a) ACCREDITED PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS S/N NAME OF LOCATION VALIDITY PERIOD INSTITUTION FROM TO 1 College of Medicine, Blantyre, 24/10/2016 23/10/2023 University of Malawi Lilongwe, Mangochi 2 Kamuzu College of Lilongwe, 13/10/2017 12/10/2024 Nursing, University of Blantyre Malawi 3 The Polytechnic, Blantyre 09/03/2018 08/03/2025 University of Malawi 4 Malawi University of Thyolo 24/10/2016 23/10/2023 Science and Technology (MUST) 5 Mzuzu University Mzuzu 13/10/2017 12/10/2024 (MZUNI) 6 Lilongwe University of Bunda, NRC, 22/12/2017 21/12/2024 Agriculture and Natural City Campus Resources (LUANAR) 7 Malawi College of Blantyre, 22/12/2017 21/12/2024 Accountancy (MCA) Lilongwe 8 Malawi Institute of Lilongwe 29/10/2018 28/10/2025 Management (MIM) b) ACCREDITED PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS S/N NAME OF LOCATION VALIDITY PERIOD INSTITUTION FROM TO 1 Catholic University of Montfort 24/10/2016 23/10/2023 Malawi (CUNIMA) Campus 2 DMI St John the Baptist Mangochi, 24/10/2016 23/10/2023 University Lilongwe 3 Nkhoma