Change in Fairview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

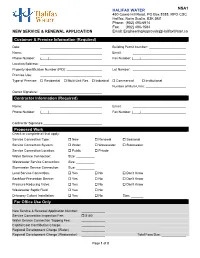

New Connection & Renewal Application

NSA1 HALIFAX WATER 450 Cowie Hill Road, PO Box 8388, RPO CSC Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 5M1 Phone: (902) 490-6914 Fax: (902) 490-1584 NEW SERVICE & RENEWAL APPLICATION Email: [email protected] Customer & Premise Information (Required) Date: Building Permit Number: Name: Email: Phone Number: ( ) Fax Number: ( ) Location/Address: Property Identification Number (PID): Lot Number: Premise Use: Type of Premise: Residential Multi-Unit Res. Industrial Commercial Institutional Number of Multi-Units: Owner Signature: Contractor Information (Required) Name: Email: Phone Number: ( ) Fax Number: ( ) Contractor Signature: Proposed Work Check or complete all that apply: Service Connection Type: New Renewal Seasonal Service Connection System: Water Wastewater Stormwater Service Connection Location: Public Private Water Service Connection: Size: Wastewater Service Connection: Size: Stormwater Service Connection: Size: Lead Service Connection: Yes No Don’t Know Backflow Prevention Device: Yes No Don’t Know Pressure Reducing Valve: Yes No Don’t Know Wastewater Septic Field: Yes No Driveway Culvert Installation: Yes No Size: For Office Use Only New Service & Renewal Application Number: Service Connection Inspection Fee: $150 Water Service Connection Tapping Fee: Capital Cost Contribution Charge: Regional Development Charge (Water) Regional Development Charge (Wastewater) Total Fees Due: Page 1 of 2 NSA1 HALIFAX WATER 450 Cowie Hill Road, PO Box 8388, RPO CSC Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 5M1 Phone: (902) 490-6914 Fax: (902) 490-1584 NEW SERVICE & RENEWAL APPLICATION Email: [email protected] Application Sketch In the space provided below, indicate all physical characteristics on, below or within the property that may impact the installation of the service connection installation or repair. Indicate if the proposed work is located on private property or within the Municipality street right-of-way. -

TABLE of CONTENTS 1.0 Background

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Background ....................................................................... 1 1.1 The Study ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The Study Process .............................................................................................. 2 1.2 Background ......................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Early Settlement ................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Community Involvement and Associations ...................................................... 4 1.5 Area Demographics ............................................................................................ 6 Population ................................................................................................................................... 6 Cohort Model .............................................................................................................................. 6 Population by Generation ........................................................................................................... 7 Income Characteristics ................................................................................................................ 7 Family Size and Structure ........................................................................................................... 8 Household Characteristics by Condition and Period of -

Lena M. Diab the Armdale Report

THE HONOURABLE THE ARMDALE REPORT LENA M. DIAB VOL. 1 • NO. 1 • FEBRUARY 2014 MLA HALIFAX ARMDALE Welcome to the first edition of the Armdale Report! It has been almost 4 months since you elected me to be your MLA. My colleagues and I have been working steadily both at the House of Assembly and in our ridings. On December 7th, we officially opened my constituency office. Located on the Armdale Rotary, our address is 2625 Joseph Howe Drive, Suite 26. Thank you to everyone who attended our open house and brought a donation of food or money to give to Feed Nova Scotia. We filled over 4 large boxes which we delivered to Feed Nova Scotia just before Christmas. I started the new year by attending various events with municipal councillors Linda Mosher (District 9), Russell Walker (District 10) and Stephen Adams (District 11). We attended the 20th annual Herring Cove Polar Bear Dip. We also shared in the wonderful New Year’s Levee festivities held at various local events. It was great to see so many people of all ages enjoy the company of family and friends. In January, I also had the opportunity to tour J.L Ilsley High School with MLA Brendan Maguire from Halifax Atlantic. We met with Principal Gordon McKelvie to discuss the current condition of the building and how we may be able to assist. As a mother of four children, I understand the impact a positive high school experience can have in shaping the future of our youth. I want to assure you that our voices have been heard. -

Fairview-Clayton Park Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park

Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park Including Former Electoral District Names Report Created for Nova Scotia Legislature Website by the Nova Scotia Legislative Library The returns as presented here are not official. Every effort has been made to make these results as accurate as possible. Return information was compiled from official electoral return reports and from newspapers of the day. The number of votes is listed as 0 if there is no information or the candidate won by acclamation. September 1, 2021 Page 1 of 44 Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park Fairview-Clayton Park In 2013, following the recommendation of the Electoral Boundaries Commission, this district was created by merging the area north of Bayers Road and west of Connaught Avenue from Halifax Chebucto; the area south of Mount St Vincent University and Lacewood Drive as well as the Washmill Drive area from Halifax Clayton Park; and the area north of Highway 102 and east of Northwest Arm Drive / Dunbrack street from Halifax Fairview. In 2021, the district lost that portion east of Joseph Howe Drive and Elliot Street to Connaught Avenue to Halifax Armdale. Member Elected Election Date Party Elected Arab, Patricia Anne 17-Aug-2021 Liberal Majority: (105) Candidate Party Votes Arab, Patricia Liberal 2892 Hussey, Joanne New Democratic Party 2787 Mosher, Nicole Progressive Conservative 1678 Richardson, Sheila G. Green Party 153 Arab, Patricia Anne 30-May-2017 Liberal Majority: (735) Candidate Party Votes Arab, Patricia -

225 KENNETH NEIL, Department of Biology, Dalhousie University

VOLUME 32, NUMBER 3 225 Fig. 1. Eulythis mellinata F. Female from Armdale, Halifax, Nova Scotia. 31 July 1972. J. Edsall. 3.5X. America at Laval (Isle Jesus), Quebec on 10 July 1967 (l male), 24 June 1973 (1 female), 1 July 1973 (1 male) (Sheppard 1975, Ann. Entomol. Soc. Quebec 20: 7), 28 June 1974 (1 male), 7 July 1974 (1 female), 29 June 1975 (l female), 18 June 1976 (1 male) and 24 June 1976 (1 male) (Sheppard, 1977, pers. comm.). The introduction of Eulythis mellinata in Nova Scotia was almost certainly recent as the specimen was collected in an area which has been intensively collected for the last 30 years, yet this is the only specimen which has been taken to date. The occur rence of the moth in two widely separated localities in eastern Canada indicates well established populations, and its occurrence in other eastern North American localities should therefore be expected. A photograph of the adult has been included to aid in identification. KENNETH NEIL, Department of Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 32(3), 1978, 225-226 OCCURRENCE OF THYMELlCUS LlNEOLA (HESPERIIDAE) IN NEWFOUNDLAND The recent rapid spread of the European Skipper, Thymelicus lineola (Ochsen heimer) in North America, particularly in the northeastern part of the continent, evi- 226 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY dently has excited considerable interest (Burns 1966, Can. Entomol. 98: 859-866; Straley 1969, J. Lepid. Soc. 23: 76; Patterson 1971, J. Lepid. Soc. 25: 222). As far as Canada is concerned it is now listed (Gregory 1975, Lyman Entomol. -

A Pocket Guide Book of Historic Halifax, Nova Scotia, from the Citadel

%*»* % sMIM \\l>t sS**// O MARI MERGES (wealth from the sea) ISTORIC HALIFAX NOVA SCOTIA FROM THE CITADEL F1039 .5.H17 1949x iResearch Library E BOOK ' " . so SO so 1^ s rr> r*-; ~T rt T T —i o os 2 °0 CNJ CM C> CN4 CM (\J CM ^ ^ 2 a Ph £ -3 ° 3 4) ZZ <u >-" *J u a «j .2 O "5 2 2 ci qj <u - S £ 5 4) . Si cj c 2 X> 2 fe ^ n U o o 2 CJ ? o N (J O CO P "S » is I 3 2 | *d P n] n< Q ° 4) M- in <A W £ O V. C W Ph s G 3 O o m _ £ 3 <U 4> <j ^ ±J •rt O — in r « 3 ° * 2 - O en D i2 i5 cd XI c s j a o 3 .,3gS cd r/l o • £ < 2 fe & * H 3 = 5 ?. cd x) <Tl Cd Ji1) U a c 4) CO r^ cd C "" cd <u £ -S M >> fi * ^ rt ~ « S o u w is a 2 <* s «i "p T3 .-2 r. o a u o t3 3 o H xi o w o ° £ S cj 5 X O Ph o O W r ^ O <L> xi en 1-3 — o -a cj — (/I •-• f) v in * 6C 60 rt > V .Sa y .a cd c Ci co "5b o 3 5 a c "d 3 is p ° u a O > 41 1X2 c -g •a c 3 o 3 o 2 O U 2 § co P fc O o % tri « S < CO CJ ^ i I i i I O I I I LO i PO T LO J, or Os o — 1 o vO SO vO S3 o SO 00 "s* 00"">lOOsOsOs rt <"-slO 'S- o N h |sj M N CM < d e<-> — o CO Ph r^ en T3 CO M '<SZ H XI .C o ^ & 2 W Oj H u c >-H £ se cd 5 > CQ CO CO 4) M ( ) 2 °»s: •= o rt o .« 2 > — .t3 J4 43 tfl 2 o £ ° o § a LO Ph JS s en CJ Cu «- C CM • o Ph UtJii h £ o «tt O ^3 3 O -a « CO CJ en -O a tj I & T3 ^4 "O <u o 51 ^^ "S 4) 4) 'en ^ 3 en CO c h "^ <n ^. -

Saint Mary's University Auditorium

1969 Saint Mary's University Auditorium Friday afternoon, October the third Nineteen hundred and sixty-nine at two-thirty o'clock PROGRAMME PROCESSIONAL ROYAL SALUTE INVOCATION PRESIDENT'S REMARKS CONFERRING OF DEGREES Receiving the Degree of Doctor of Letters (Honoris Causa) Walter Donald O'Hearn (posthumously) To be accepted by Walter D. O'Hearn, Jr. Thomas Head Raddall Receiving the Degree of Doctor of Laws (Honoris Causa) Jean Victor Allard Victor deBedia Oland ADDRESS TO THE GRADUATES Thomas Head Raddall, F.R.S.C., LL.D., D.Litt. GOD SAVE THE QUEEN RECESSIONAL Guests are requested to remain standing until the academic procession has left the auditorium THE STADACONA BAND Director of Music: Lieutenant J. McGuire, C.D., R.C.N, appearing by kind permission of Vice Admiral J. C. O'Brien, C.D., R.C.N. Commander Maritime Command BACHELOR OF ARTS Norma Helen Adams Waverley, Nova Scotia John Thompson Aikens Halifax, Nova Scotia Mary Eileen Anderson (Magna Cum Laude) . Halifax, Nova Scotia Stephen William Anderson Herring Cove, Nova Scotia Francis Xavier Babin Liverpool, Nova Scotia James Arthur Barrett Halifax, Nova Scotia Gordon Philip Bartlett Fairview, Nova Scotia Simon Emersoii Binder Kitchener, Ontario Brian Redvers Cainey New Glasgow, Nova Scotia Attilio Carlo Diliberatore Halifax, Nova Scotia Frederick Brien Dolan Toronto, Ontario Thomas Joseph Doucette Halifax, Nova Scotia David William Ferguson Bridgewater, Nova Scotia Ruth Elizabeth Fisher Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Ronald Christopher Gale Cornerbrook, Newfoundland Patrick Glendon Giddings Montague, P.E.I. Margaret Janice Gillen Armdale, Nova Scotia Grant Mansfield Josey Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia Wayne Louis Keddy King's County, Nova Scotia Gary Wayne Kelly : Halifax, Nova Scotia John Malcolm Kendall Halifax, Nova Scotia Owen Michael Kennedy St. -

Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, Ns 1972 - 2016

MAPPING THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONDOMINIUMS IN HALIFAX, NS 1972 - 2016 by Colin K. Werle Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of GEOG 4526 for the Degree Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies Saint Mary’s University Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada © Colin Werle, 2017 April, 2017 Members of the Examining Committee: Dr. Mathew Novak (Supervisor) Assistant Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Saint Mary’s University Dr. Ryan Gibson School of Environmental Design and Rural Development University of Guelph ABSTRACT Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, NS from 1972 – 2016 by Colin K. Werle This thesis offers foundational insight into the spatial and temporal patterns of condominium development in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Characteristics that are analysed include: age, assessed values, building types, heights, number of units, and amenities. Results show that condominium development in Halifax first appeared in the suburbs in the 1970s, with recent activity occurring in more central areas. The greatest rate of development was experienced during a condominium boom in the late 1980s, however, development has been picking up over the last decade. Apartment style buildings are the major type of developments, with an average building size of 46.52 units. Similar to other markets in Canada, Halifax’s condominium growth does appear to be corresponding with patterns of re- centralization after decades of peripheral growth in the second half of the twentieth-century. April, 2017 ii RÉSUMÉ Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, NS from 1972 – 2016 by Colin K. Werle Cette dissertation donnera un aperçu des tendances spatiales et temporelles de base sur le développement des condominiums à Halifax (Nouvelle-Écosse). -

6140 Quinpool Road Halifax, Nova Scotia

FOR LEASE 6140 Quinpool Road Halifax, Nova Scotia Prime Quinpool Road Retail +/- 1,830 - 3,750 sf Lower-Level Retail Space | Lease Rate: $30.00 psf Gross PROPERTY OVERVIEW PROPERTY TYPE 2 storey commercial building, currently undergoing Easily accessible, Tenant parking substantial renovations. 20 + bus routes options available FEATURES Excellent opportunity to occupy 1,830 sf of space on the lower level of a retail building on a high traffic thoroughfare. This lower level space offers barrier free Over 30,000 cars High pedestrian access and a ceiling height of 10’ clear. A blank slate, passing daily traffic area tenants can customize the space based on their needs. AVAILABLE SPACE Approximately 1,830 sf with potential for up to 3,750 sf Building signage Barrier free access PANDEMIC-PREPARED with excellent with wheelchair roadside visibility elevator If a tenant is forced to close due to a pandemic (or state of emergency), they are not required to pay rent. Contact MEAGHAN MACDOUGALL Retail Sales & Leasing +1 902 266 6211 [email protected] FOR LEASE Aerial6140 / Location QuinpoolMap Road Halifax, Nova Scotia HALIFAX NORTH END HALIFAX COMMONS DOWNTOWN HALIFAX 6140 QUINPOOL ROAD QEII HEALTH SCIENCES CENTRE DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY ARMDALE ROTARY LOCATION Quinpool Road lies on the western edge of the Halifax Commons and serves as one of Halifax’s main arterial roads connecting the downtown core of Halifax with the Armdale Rotary, leading to the West End, Herring Cove, Armdale, Clayton Park, Fairview and Highway 102. You’ll be joining other prime retailers such as the NSLC, Wendy’s, TD Starbucks, Atlantic Superstore, Canadian Tire and many more. -

Approved by the Halifax Water Board January 30, 2020

Approved by the Halifax Water Board January 30, 2020 HALIFAX WATER Five-Year Business Plan 2020/21 to 2024/25 Glossary AM Asset Management AMIT Asset Management Implementation Team AMP Asset Management Plan AO Aesthetic Objective AMI Advanced Metering Infrastructure AWWA American Water Works Association BLT Beechville-Lakeside Timberlea BMPs Best Management Practices BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand BPF Biosolids Processing Facility CapEx Capital Expenditures CBOD Carbonaceous Biochemical Oxygen Demand CCME Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment CCTV Closed Circuit Television CEC Contaminants of Emerging Concern CIPP Cured in Place Pipe CFIA Canadian Food Inspection Agency COMFIT Community Feed-In Tariff COS Cost of Service CMMS Computerized Maintenance Management System CRM Customer Relationship Management CSO Combined Sewer Overflow CSMMW Canada-Wide Strategy for the Management of Municipal Wastewater Effluent CUPE Canadian Union of Public Employees CWWF Clean Water and Wastewater Fund dia. Diameter EMAP Energy Management Action Plan EMP Emergency Management Plan EMS Environmental Management System EMSC Energy Management Steering Committee EMO Energy Management Opportunities EPWWTF Eastern Passage Wastewater Treatment Facility ERA Environmental Risk Assessment ERM Enterprise Risk Management ERP Enterprise Resource Planning GHG Greenhouse Gas GIS Geographic Information System HHSP Halifax Harbour Solutions Project HRM Halifax Regional Municipality HRWC Halifax Regional Water Commission I&I Inflow & Infiltration ICI Industrial, -

Regional Centre Secondary Municipal Planning Strategy (Package A) REGIONAL CENTRE SECONDARY MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY

Regional Centre Secondary Municipal Planning Strategy (PAckage A) REGIONAL CENTRE SECONDARY MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY THIS IS TO CERTIFY that this is a true copy of the Regional Centre Secondary Municipal Planning Strategy which was passed by a majority vote of the Council of the Halifax Regional Municipality at a duly called meeting held on the 18th day of September, 2019, and reviewed by Municipal Affairs and Housing on the 31st day of October, 2019, and is in effect as of the 30th day of November, 2019. GIVEN UNDER THE HAND of the Municipal Clerk and under the Corporate Seal of the Halifax Regional Municipality this _____ day of ______________________, 201__. __________________________ Kevin Arjoon Municipal Clerk II | REGIONAL CENTRE SECONDARY MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY | Acknowledgements The Halifax Regional Municipality (Municipality) recognizes the many stakeholders and residents who shared their thoughts and aspirations for the Regional Centre through the extensive community engagement process of developing this Plan. The Municipality would also like to recognize the input members of the Community Design Advisory Committee (CDAC) devoted to the development of the 2018 Regional Centre Secondary Planning Strategy (Centre Plan). They include the following: Fred Morley, Chair Councillor Sam Austin - District 5 - Dartmouth Centre Deputy Mayor Waye Mason - District 7 - Halifax South Downtown Councillor Lindell Smith - District 8 - Halifax Peninsula North Councillor Shawn Cleary - District 9 - Halifax West Armdale Councillor Richard Zurawski - District 12 - Timberlea-Beechville-Clayton Park-Wedgewood Willam Book Eric Burchill Christopher Daly Dale Godsoe Jenna Khoury-Hanna Reg Manzer Rima Thomeh Gaynor Watson-Creed Photo credits: TJ Maguire; River Heim, Maritime River Photography | REGIONAL CENTRE SECONDARY MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY | III Preface The Regional Centre is the political, cultural and economic heart of the Halifax Regional Municipality (Municipality), and Nova Scotia’s capital city. -

Tax Relief for Non-Profit Organizations Program: Fiscal Year 2019-2020

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 15.2.1 Halifax Regional Council February 11, 2020 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: Russell Walker, Chair, Audit and Finance Standing Committee DATE: January 21, 2020 SUBJECT: Tax Relief for Non-Profit Organizations Program: Fiscal Year 2019-2020. Part 3 – Proposed Amendments to Schedules ORIGIN Audit and Finance Standing Committee January 21, 2020 meeting, Item No. 12.3.1 LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Administrative Order One, Schedule 2, Audit and Finance Standing Committee, Terms of Reference, section 8(c), Other Duties states: ‘The Audit and Finance Standing Committee shall review and make recommendations on proposals coming to the Council outside of the annual budget or tender process including: (c) proposed changes in any operating or project budget items; RECOMMENDATION The Audit and Finance Standing Committee recommends that Halifax Regional Council approve: 1. Reinstatement of Abenaki Aquatic Club, 20A-22 Swanton Drive, Dartmouth and the Senobe Aquatic Club, 8 Nowlan Street and a Portion of PID#00636290 Prince Albert Road, Dartmouth to Schedule 26, effective April 1, 2019, at a combined estimated cost of $21,948 from Operating Account M311-8006; 2. Reinstatement of the Atlantic Division Association: Canoe-Kayak Canada, 34 Boathouse Lane, Dartmouth to Schedule 27, effective April 1, 2019, at an estimated cost of $5,255 from Operating Account M311-8006; 3. Removal of ABC Housing Cooperative Limited, 1F Arklow Drive, Dartmouth, from Schedule 30, effective April 1, 2019, at an estimated saving of $323 to the tax relief program; 4.