Analysis on the Alleged Similarities Between the Songs Blurred Lines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

CS Lewis and JW Dunne

Volume 37 Number 2 Article 5 Spring 4-17-2019 The Last Serialist: C.S. Lewis and J.W. Dunne Guy W B Inchbald Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Inchbald, Guy W B (2019) "The Last Serialist: C.S. Lewis and J.W. Dunne," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 37 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract C.S. Lewis was influenced yb Serialism, a theory of time, dreams and immortality proposed by J.W. Dunne. The closing chapters of the final Chronicle of Narnia, The Last Battle, are examined here. Relevant aspects of Dunne’s theory are drawn out and his known influence on the works of Lewis er visited. -

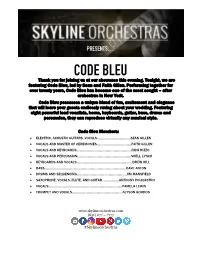

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

90'S Medley Rihanna Medley Motown Medley Prince

Adele - Rolling in the Deep Jackson 5 - ABC Outkast - Miss Jackson 90’S MEDLEY Alabama Shakes - Hold on James Brown - Get Up Oa That Thing Outkast - Rosa Parks TLC Alicia Keys - Empire State of Mind James and Bobby Purify - Shake A Tail Feather Patrice Ruschen - Forget Me Nots Usher Alicia Keys - If I Ain’t Got You James Blake - Limit To Your Love Percy Sledge - You Really Got a Hold On Me Montell Jordan Al Green - Let’s Stay Together Jamie XX - Good Times Pharrell – Happy Mark Morrison Al Green - Take Me to the River Janelle Monae - Tightrope Prince – I Wanna Be Your Lover Next Amy Whinehouse - Valerie Jerry Lee Lewis - Great Balls of Fire Prince - Kiss Beck – Where It’s At Justin Timberlake - Can’t Stop The Feeling Ray Charles - Georgia Beyonce – Crazy In Love Justin Timberlake - Rock Your Body R Kelly - Remix to Ignition RIHANNA MEDLEY Beyonce - Love on Top King Harvest - Dancing in the Moonlight Sade - By Your Side What’s My Name Beyonce - Party Kendrick Lamar – If These Walls Could Talk Sade - Smooth Operator We Found Love Bill Withers - Ain’t No Sunshine Leon Bridges - Coming Home Sade - Sweetest Taboo Work Blondie – Rapture Lil Nas X - Old Town Road Sam Cooke - Wonderful World Blood Orange - You’re Not Good Enough Sam Cooke - Cupid Lionel Richie - All Night Long MOTOWN MEDLEY Bob Carlisle/Je Carson - Butterfly Kisses Little Richard - Good Golly Miss Molly Sam Cooke - Twistin’ Your Love Keeps Lifting Me Higher and Higher Bruno Mars - 24k Magic Lizzo - Juice Sam Cooke – You Send Me You Really Got a Hold On Me Bruno Mars - Treasure -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

12 BM~~~R~~~F5tftr{Ilfution 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 CENTRAL DISTRICT of CALIFORNIA, WESTERN DIVISION

Case 2:13-cv-06004-JAK-AGR Document 385 Filed 05/11/15 Page 1 of 38 Page ID #:11528 1 KING, HOLMES, PATERNO & BERLINER, LLP HOWARD E. KING, ESQ., STATE BARNO. 77012 2 STEPHEN D. ROTHSCHILD, ESQ., STATE BARNO. 132514 [email protected] 3 SETHMILLER,ESQ., STATEBARNO. 175130 [email protected] 4 1900 A VENUE OF THE STARS, 25TH FLOOR Los ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90067-4506 5 TELEPHONE: (31 0) 282-8989 FACSIMILE: (31 0) 282-8903 6 Attorneys for Plaintiffs and Counter- 7 Defendants PHARRELL WILLIAMS, ROBIN THICKE and CLIFFORD 8 HARRIS, JR. and Counter-Defendants MORE WATER FROM NAZARETH 9 PUBLISHING, INC., PAULA MAXINE PATTON individ}l~ly and d/b/a 10 HADDINGTON MUSIC, STAR TRAK ENTERT~NT GEFFEN 11 RECORDS, INTERSCOPE RECORDS, 12 BM~~~R~~~f5tftr{ilfuTION 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA, WESTERN DIVISION 15 PHARRELL WILLIAMS, an CASE NO. CV13-06004-JAK ~AGRx) individual; ROBIN THICKE, an Hon. John A. Kronstadt, Ctrm 50 16 individua~ and CLIFFORD HARRIS, JR., an in ividual, CORRECTED NOTICE OF 17 MOTION AND MOTION OF Plaintiffs, PHARRELL WILLIAMS, ROBIN 18 THICKE AND MORE WATER vs. FROM NAZARETH PUBLISHING, 19 INC. FOR JUDGMENT AS A BRIDGEPORT MUSIC INC., a MATTER OF LAW, 20 Michi§an CODJoration; FRAN:KiE DECLARATORY RELIEF, A NEW CHRI TIAN GAYE, an individual; TRIAL, OR REMITTITUR; 21 MARVIN GAYE lib an individual; NONA MARVISA AYE, an MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND 22 individual; and DOES 1 through 10, AUTHORITIES inclusive, 23 Date: June 29, 2015 Defendants. Time: 8:30a.m. 24 Ctrm.: 750 25 AND RELATED COUNTERCLAIMS. -

Band Song-List

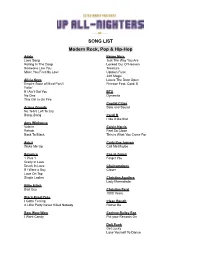

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected]

Boston College Law Review Volume 59 | Issue 6 Article 2 7-11-2018 Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases, 59 B.C.L. Rev. 1873 (2018), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol59/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR USE AVOIDANCE IN MUSIC CASES EDWARD LEE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1874 I. FAIR USE’S RELEVANCE TO MUSIC COMPOSITION ................................................................ 1878 A. Fair Use and the “Borrowing” of Copyrighted Content .................................................. 1879 1. Transformative Works ................................................................................................. 1879 2. Examples of Transformative Works ............................................................................ 1885 B. Borrowing in Music Composition ................................................................................... -

PERHAPS LOVE Inspired by the John Denver Song Week #2 of an 8-Week “Songs of Life” Series June 13, 2021 Rev

PERHAPS LOVE Inspired by the John Denver Song Week #2 of an 8-week “Songs of Life” Series June 13, 2021 Rev. Richard Maraj SOLO Guest artist Todd Herzog sings the message title song, “Perhaps Love” Perhaps love is like a resting place, a shelter from the storm It exists to give you comfort; it is there to keep you warm And in those times of trouble when you are most alone The memory of love will bring you home Perhaps love is like a window; perhaps an open door It invites you to come closer; it wants to show you more And even if you lose yourself and don't know what to do The memory of love will see you through Oh, love to some is like a cloud, to some as strong as steel For some a way of living, for some a way to feel And some say love is holding on and some say letting go And some say love is everything and some say they don't know Perhaps love is like the ocean, full of conflict, full of change Like a fire when it's cold outside or thunder when it rains If I should live forever and all my dreams come true, My memories of love will be of you Some say love is holding on and some say letting go And some say love is everything and some say they don’t know Perhaps love is like the ocean, full of conflict, full of change Like a fire when it’s cold outside or thunder when it rains If I should live forever and all my dreams come true, My memories of love will be of you [Congregation applauds] MESSAGE Rev. -

Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don Mclean 1972 4

AS VOTED AT OLDIESBOARD.COM 10/30/17 THROUGH 12/4/17 CONGRATULATIONS TO “HEY JUDE”, THE #1 SELECTION FOR THE 19 TH TIME IN 20 YEARS! Ti tle Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don McLean 1972 4 Light My Fire Doors 1967 5 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 7 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 8 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 9 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 10 Ain't No Mount ain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 11 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 12 Because Dave Clark Five 1964 13 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 14 Cherish Association 1966 15 She Loves You Beatles 1964 16 Hotel California Eagles 1977 17 St airway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 18 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 19 My Girl Temptations 1965 20 Let It Be Beatles 1970 21 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 22 Downtown Petula Clark 1965 23 Since I Don't Have You Skyliners 1959 24 To Sir With Love Lul u 1967 25 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 26 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 27 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 28 You Really Got Me Kinks 19 64 29 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 30 The Rain The Park & Ot her Things Cowsills 1967 31 A Hard Day's Night Beatles 1964 32 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 33 Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 34 Imagine John Lennon 1971 35 I Only Have Eyes For You Flamingos 1959 36 Waterloo Sunset Kinks 1967 37 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 76 -92 38 Sugar Sugar Archies 1969 39 What's -

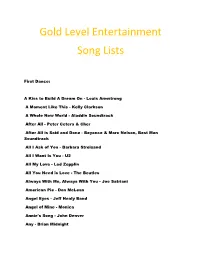

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour