Top 5 Ghost Hunting Mistakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chupacabra Mystery

SI May June 11 CUT_SI new design masters 3/25/11 11:29 AM Page 45 Slaying the Vampire Solving the Chupacabra Mystery The mysterious vampire beast el chupacabra is said to have terrorized people around the world since at least 1995. A five-year skeptical investigation reveals the surprising origin of this monster, finding that there’s more to this vampire than meets the eye. BENJAMIN RADFORD approximately four-feet tall that had igfoot, the mysterious creature said to roam the thin arms and legs with three fingers or North American wilderness, is named after what it toes at the end of each (Corrales 1997). leaves behind: big footprints. Bigfoot’s Hispanic It had no ears or nose but instead two B small airholes and long spikes down its cousin, el chupacabra, is also known for what it leaves behind: back (see figure 1). When the beast was dead animals mysteriously drained of blood. Goats are said later reported in other countries, it took to be its favorite prey (chupacabra means goat sucker in Span- on a very different form (see figure 2). A few were found dead (for example, in ish), and it is the world’s third best-known mystery creature Nicaragua and Texas), and the carcasses (after Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster). turned out to be small four-legged an- imals from the Canidae family (such as El chupacabra first appeared in 1995 mense confusion and contradiction” dogs and coyotes). after Madelyne Tolentino, an eyewit- surrounding el chupacabra, making it The next step was identifying and ness in Puerto Rico, provided a detailed “almost impossible to distinguish fact analyzing the central claims about el description of the bloodsucker. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: OLN Announces New Fall Primetime Programming (Toronto – August 10, 2010) The success of hit series UFO Hunters and MonsterQuest this Summer has moved OLN up into the Top 10 most-watched, specialty channels for adults 18-49. OLN today announced the exciting mix of new and returning primetime series to continue the momentum this Fall. New series Man v. Food, Conspiracy Theory with Jesse Ventura and the latest from Canadian survival expert Les Stroud, Beyond Survival, join the adrenaline rush of returning favourites UFO Hunters, MonsterQuest and Operation Repo, and new seasons of Destination Truth, Ghost Hunters and Canadian series Mantracker. Artwork and returning show descriptions are available at www.rogersmediatv.ca “Canadian audiences are clearly big fans of the programming on OLN, making it such a popular destination this Summer,” commented Alain Strati Vice President, Specialty TV and Development, Rogers Media Television. “We hope to build upon our success this Fall with an even stronger dose of action and adventure programming.” New series premieres on OLN are as follows: Man v. Food, Seasons 1 - 3: Monday to Friday at 9:30pm ET/PT starting Monday, August 16th Passionate foodie Adam Richman is on a hunger quest to find the most mouthwatering pigout joints in the United States. After getting to know the people behind the dishes from the staff to the loyal patrons, Adam seeks to find out what makes these places so legendary. He'll tackle their famous food challenges designed to test man's gastronomic limits. Let Man v. Food be your guide to the best chow America has to offer. -

Bigfoot at 50 Evaluating a Half-Century of Bigfoot Evidence

B I C F O O T Bigfoot at 50 Evaluating a Half-Century of Bigfoot Evidence The question of Bigfoot's existence comes down to the claim that "Where there's smoke there's fire. " The evidence suggests that there are enough sources of error that there does nc have to be a hidden creature lurking amid the unsubstantiated cases. BENJAMIN RADFORD hough sightings of the North American Bigfoot date back to the 1830s (Bord 1982), interest in Bigfoot Tgrew rapidly during the second half of the twentieth century. This was spurred on by many magazine articles of the time, most seminally a December 1959 True magazine article describing the discovery of large, mysterious foot- prints the year before in Bluff Creek, California. A half century later, the question of Bigfoot's existence remains open. Bigfoot is still sought, the pursuit kept alive by a steady stream of sightings, occasional photos or foot- print finds, and sporadic media coverage. But what evidence has been gathered over the course of fifty years? And what conclusions can we 4mw from that evidence? / SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Manh/Apr**^ 29 Most Bigfoot investigators favor one theory of Bigfoot's ori- gin or existence and stake their reputations on it, sniping at oth- ers who don't share their views. Many times, what one investi- gator sees as clear evidence of Bigfoot another will dismiss out of hand. In July 2000, curious tracks were found on the Lower Hoh Indian Reservation in Washington state. Bigfoot tracker Cliff Crook claimed that die footprints were "for sure a Bigfoot," though Jeffrey Meldrum, an associate professor of bio- logical sciences at Idaho State University (and member of the Bigfoot Field Research Organization, BFRO) decided that there was not enough evidence to pursue the matter (Big Disagreement Afoot 2000). -

Spooky Plumbers-Turned-Ghost-Hunters to Speak at University of New Hampshire

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Media Relations UNH Publications and Documents 10-10-2007 Spooky Plumbers-Turned-Ghost-Hunters To Speak At University Of New Hampshire Jody Record UNH Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/news Recommended Citation Record, Jody, "Spooky Plumbers-Turned-Ghost-Hunters To Speak At University Of New Hampshire" (2007). UNH Today. 887. https://scholars.unh.edu/news/887 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNH Publications and Documents at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Relations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spooky Plumbers-Turned-Ghost-Hunters to Speak at University of New Hampshire 9/11/17, 154 PM Spooky Plumbers-Turned-Ghost-Hunters To Speak At University Of New Hampshire Contact: Jody Record 603-862-1462 UNH Media Relations October 10, 2007 DURHAM, N. H. - Believers will want to come early. Skeptics who think what they hear will debunk anyone’s beliefs in the paranormal should, too; the Oct. 24 presentation at the University of New Hampshire by the stars of the Sci-Fi Channel’s popular “Ghost Hunters” is expected to be such a hit that organizers fear they will have to turn people away. And you can forget haunting the planners in advance for a seat. The talk is first-come, first- serve. “We’ve never had as many phone calls for an event as we have in the past three or four weeks for this,” says David Zamansky, assistant director of the Memorial Union Building at UNH. -

The Biography of America's Lake Monster

REVIEWS] The Biography of America’s Lake Monster BENJAMIN RADFORD obert Bartholomew and his broth- er Paul grew up near the shores Rof Lake Champlain, which not The Untold Story of Champ: A Social History of America’s only sparked an early interest in the Loch Ness Monster. By Robert E. Bartholomew. lake monster said to dwell within the State University of New York Press, lake but also steeped them in the social Albany, New York, 2012. ISBN: 978-1-4384-4484-0. and cultural context of the mysterious 253 pp. Paperback, $24.95. beastie. In his new book, The Untold Story of Champ: A Social History of America’s Loch Ness Monster, Robert, a sociologist, Fortean investigator, and former broadcast journalist, takes a fresh look at Champ, long dubbed “America’s Loch Ness Monster.” Roy Mackal, and others who con- the Mansi photo, “New Information There have only been a handful of vened a 1981 conference titled, “Does Surfaces on ‘World’s Best Lake Mon- other books dealing in any depth or Champ Exist? A Scientific Seminar.” ster Photo,’ Raising Questions,” May/ scholarship with Champ, among them The intrigue between and among these June 2013.) Joe Zarzynski’s Champ: Beyond the Leg- researchers is interesting enough to fill Like virtually all “unexplained” phe- end, and of course Lake Monster Mys- several chapters. nomena, the history of Champ is in teries: Investigating the World’s Most There are several good books about part a history of hoaxes, and the book Elusive Creatures, coauthored by Joe the people involved in the search for examines several of them in detail, in- Nickell and myself. -

Mistaken Memories of Vampires: Pseudohistories of the Chupacabra As Well-Known Monsters Go, the Chupacabra Is of Very Recent Vintage, First Appearing in 1995

Mistaken Memories of Vampires: Pseudohistories of the Chupacabra As well-known monsters go, the chupacabra is of very recent vintage, first appearing in 1995. However, some writers have created pseudohistories and claimed a false antiquity for the Hispanic vampire beast. These examples provide a fascinating look at cryptozoological folklore in the making. BENJAMIN RADFORD ost people assume that the chupacabra, like its acy-laden Frankenstein scenario. Not coincidentally, these two origin stories cryptozoological brethren Bigfoot and Nessie, dates are identical to those of Sil, a chupaca- Mback many decades or centuries. However, as dis- bra-like monster in the film Species (see Figure 1 and Radford 2014). cussed in my book Tracking the Chupacabra: The Vampire The alien/Frankenstein’s monster Beast in Fact, Fiction, and Folklore and in the pages of the explanation, though embraced by SKEPTICAL INQUIRER, the origin of the mysterious vampire many Puerto Ricans and others soon after the chupacabra’s 1995 appear- beast el chupacabra can be traced back to a Puerto Rican ance, was unsatisfactory (and perhaps eyewitness who saw the 1995 film Species, which featured too outlandish) to some, who then offered their own histories of the a nearly identical monster. Though both vampire legends vampire beast. A blank slate history and “mysterious” animal predation date back many centu- creates an information vacuum easily ries, there seems to be no evidence of any blood-sucking filled by mystery-mongering specu- lation. (For analysis of historical ch- “chupacabra” before the 1990s. upacabra claims since the 1950s, see my SI columns “The Mystery of the The beast turned twenty last year, accounts of encounters with unknown Texas Chupacabra” in the March/ and its recent vintage poses a thorny corporeal creatures. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Kontakty Z Duchami. Odtajnione Sprawy Z Archiwów T.A.P.S

KONTaKTY z duchami Jason Hawes Grant wilson MicHael Jan FriedMan KONTaKTY z duchami OdtajniOne sprawy z archiwów t.a.p.s. Redakcja: Dominika Dudarew Skład komputerowy: Piotr Pisiak Projekt okładki: Piotr Pisiak Tłumaczenie: Łukasz Głowacki Korekta: Marzena Żukowska Wydanie I Białystok 2010 ISBN 978-83-7377-427-8 Copyright © 2009 by Jason Hawes, Grant Wilson and Michael Jan Friedman. GHOST HUNTERS ® is a registered trademark and service mark of Pilgrim Films and Television, Inc. in the United States and foreign countries. © Copyright for this edition by Studio Astropsychologii, Białystok 2010. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone. Żadna część tej publikacji nie może być powielana ani rozpowszechniana za pomocą urządzeń elektronicznych, mechanicznych, kopiujących, nagrywających i innych bez pisemnej zgody posiadaczy praw autorskich. 15-762 Białystok ul. Antoniuk Fabr. 55/24 85 662 92 67 – redakcja 85 654 78 06 – sekretariat 85 653 13 03 – dział handlowy – hurt 85 654 78 35 – sklep firmowy „Talizman” – detal www.studioastro.pl e-mail: [email protected] Więcej informacji znajdziesz na portalu www.psychotronika.pl PRINTED IN POLAND Niniejszą książkę oraz całą moją pracę dedykuję przede wszyst- kim mojej żonie, Kristen, która mnie wspierała i postawiła na nogi, gdy byłem przygnębiony. Kocham Cię nie tylko jako swoją żonę, ale również – poczynając od siódmej klasy szkoły – jako mojego najlepszego przyjaciela. Po drugie, książkę tę również dedykuję piątce moich dzieci, któ- re dzielnie znosiły pasję ojca i dały mi czas, abym mógł osiągnąć to, co osiągnąłem. Dzięki Wam wszystkim czuję się młody, to Wy pokazaliście mi, jak ważna jest każda chwila spędzona razem. -

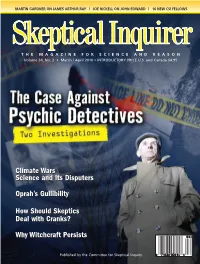

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: a Late Modern Enchantment

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: A Late Modern Enchantment Daniel S. Wise New Haven, CT Bachelor oF Arts, Florida State University, 2010 Master oF Arts, Florida State University, 2012 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty oF the University oF Virginia in Candidacy For the Degree oF Doctor oF Philosophy Department oF Religious Studies University oF Virginia November, 2020 Committee Members: Erik Braun Jack Hamilton Matthew S. Hedstrom Heather A. Warren Contents Acknowledgments 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 5 Chapter 2 From Spiritualism to Ghost Hunting 27 Chapter 3 Ghost Hunting and Scientism 64 Chapter 4 Ghost Hunters and Demonic Enchantment 96 Chapter 5 Ghost Hunters and Media 123 Chapter 6 Ghost Hunting and Spirituality 156 Chapter 7 Conclusion 188 Bibliography 196 Acknowledgments The journey toward competing this dissertation was longer than I had planned and sometimes bumpy. In the end, I Feel like I have a lot to be thankFul For. I received graduate student Funding From the University oF Virginia along with a travel grant that allowed me to attend a ghost hunt and a paranormal convention out oF state. The Skinner Scholarship administered by St. Paul’s Memorial Church in Charlottesville also supported me For many years. I would like to thank the members oF my committee For their support and For taking the time to comb through this dissertation. Thank you Heather Warren, Erik Braun, and Jack Hamilton. I especially want to thank my advisor Matthew Hedstrom. He accepted me on board even though I took the unconventional path oF being admitted to UVA to study Judaism and Christianity in antiquity. -

Chupacabra Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHUPACABRA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Roland Smith | 304 pages | 20 Jun 2016 | Scholastic US | 9780545178181 | English | United States Chupacabra PDF Book Though goats are said to be its favorite prey chupacabra means "goat sucker" in Spanish , it has have also been blamed for attacks on cats, rabbits, dogs, chickens, and other animals. Visit the state elections site. The name comes from the animal's reported vampirism —the chupacabra is said to attack and drink the blood of livestock , including goats. Retrieved 26 July She noticed some significant differences between the animal and her "Texas Blue Dog. Each of the animals was reported to have had its body bled dry through a series of small circular incisions. External Websites. These chupacabras were smaller and stood upon four feet. El Vocero. Wizards of the Coast. Chupacabra , in Latin American popular legend , a monstrous creature that attacks animals and consumes their blood. See Article History. Parapsychology Death and culture Parapsychology Scientific literacy. Dead chupacabras were subjected to DNA tests and in every instance the body has been identified as a dog, coyote, raccoon, or other common mammal — usually stricken with a parasitic infection that caused the animal to lose its fur and take on a gaunt, monstrous appearance. Forum posts. They characterized it has having large oval red eyes that sometimes glowed, gray skin, a long snake-like tongue, fangs, and long spinal quills that may double as wings. Archived from the original on 14 September For the Nov 3 election: States are making it easier for citizens to vote absentee by mail this year due to the coronavirus. -

Raising the Bar for Investigating Paranormal Claims ROBERT CARROLL

SI Sept/Oct pgs_SI MJ 2010 7/22/10 4:42 PM Page 56 B O O K R E V I E W S Raising the Bar for Investigating Paranormal Claims ROBERT CARROLL Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries. By Benjamin Radford. Rhombus Publishing Co., Corrales, New Mexico, 2010. 311 pp. Softcover, $16.95. n a chapter on how not to investigate Scien tific Paranormal Investigation would the paranormal in his new book, be a valuable addition to the library of IScientific Paranormal Investigation, every journalist and skeptic. But the thou- Benjamin Radford jokes that the entire sands of people who investigate weird or chapter could consist of just two words: mysterious things and the millions of watch television. He could have advised readers and viewers who follow their in - the reader to pick up almost any book vestigations would benefit the most. on ghosts, demons, spirits, aliens, lake I won’t relieve the lazy reader of the monsters, crop circles, the chupacabra, obligation to read Radford’s book by or other “strange and bizarre” things. summarizing the principles of a proper The bar for paranormal investigation in scientific investigation. Here I will sim- the popular media has been set very low, ply note that the goal of a proper inves- as evidenced by the overall poor quality tigation of the paranormal is neither to of work produced so far. Radford hopes prove nor disprove any particular claim. to raise the bar by clarifying and exem- Radford puts it this way: “Good science plifying the standards that should guide regularly reports on his field investiga- is not about advocacy; while all scien- a scientific investigator.